Abstract

The introduction of domesticated plants and animals into Britain during the Neolithic cultural period between 5,200 and 4,500 years ago is viewed either as a rapid event1 or as a gradual process that lasted for more than a millennium2. Here we measure stable carbon isotopes present in bone to investigate the dietary habits of Britons over the Neolithic period and the preceding 3,800 years (the Mesolithic period). We find that there was a rapid and complete change from a marine- to a terrestrial-based diet among both coastal and inland dwellers at the onset of the Neolithic period, which coincided with the first appearance of domesticates. As well as arguing against a slow, gradual adoption of agriculture and animal husbandry by Mesolithic societies, our results indicate that the attraction of the new farming lifestyle must have been strong enough to persuade even coastal dwellers to abandon their successful fishing practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Stable carbon isotopes in human bone collagen act as indicators of past dietary intake3 because marine and terrestrial dietary proteins leave different 'signatures'4. Consumption of cereal crops that use the C3 photosynthetic pathway and of farmed animals should result in a 'terrestrial' bone-collagen carbon-isotope signature (δ13C = −20 ± 1‰, where δ13C represents the 13C/12C ratio), whereas marine foods give a much higher 13C content (δ13C = −12 ± 1‰).

Archaeological evidence for the use of marine foods during the British Mesolithic is limited because very few coastal sites survived the rising sea levels of the more recent Holocene epoch. Some of the best-known exceptions are the late Mesolithic shell middens of western Scotland5,6. Other areas of Atlantic Europe, most notably southern Scandinavia and Brittany, present strong archaeological and isotopic evidence of marine-based economies at this time.

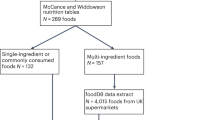

We have measured and collated6,7,8 the carbon-isotope values of bone collagen of 164 early Neolithic (5,200–4,500 yr bp) and 19 Mesolithic (9,000–5,200 yr bp) British humans. The Neolithic sample is derived from a range of contexts, including causewayed enclosures, chambered tombs, caves and stray finds, from both inland and coastal locations. Although individuals from inland and putative 'élite' contexts are more prominently represented, the results from all of these contexts are unanimous.

Figure 1 shows that, with few exceptions, individuals living near the coast in the Mesolithic show a moderate-to-strong marine isotope signal (for four humans from two inland sites, δ13C = −19.6 ± 0.8; for fifteen humans from eight coastal sites, δ13C = −16.2 ± 2.8), and that all of the Neolithic humans show a strongly terrestrial isotope signal (for 99 humans from 25 inland sites, δ13C = −20.7 ± 0.7; for 68 humans from 19 coastal sites, δ13C = −20.8 ± 0.7). These data are comparable with results obtained in Denmark, which also show a rapid dietary change in humans between the Mesolithic and Neolithic at about the same time9,10.

There is a sharp change in the carbon-isotope ratio at around 5,200 yr bp (about 4,000 calendar yr bc; dotted line) from a diet consisting of marine foods to one dominated by terrestrial protein. This period coincides with the onset of the Neolithic period in Britain. Because of uncertainties in the size of the marine reservoir effect on radiocarbon dates, we have not attempted to calibrate the data here; however, for individuals with typical marine δ13C values (about −12‰), radiocarbon dates should be corrected by roughly 400 radiocarbon years.

From our findings, we conclude that there was a sudden and marked dietary shift associated with the onset of the Neolithic period in Britain, arguing against a gradual uptake of domesticated plants and animals into Mesolithic society2. Marine foods, for whatever reason, seem to have been comprehensively abandoned from the beginning of the Neolithic in Britain.

References

Childe, V. G. Man Makes Himself (Watts, London, 1936).

Dennell, R. W. European Economic Prehistory (Academic, London, 1983).

Schwarcz, H. & Schoeninger, M. Yb. Phys. Anthropol. 34, 283–321 (1991).

Schoeninger, M., DeNiro, M. & Tauber, H. Science 220, 1381–1383 (1983).

Mellars, P. A. Excavations on Oronsay (Edinburgh Univ. Press, Edinburgh, 1987).

Schulting, R. J. & Richards, M. P. Eur. J. Archaeol. 5, 147–189 (2002).

Richards, M. P. & Hedges, R. E. M. Antiquity 73, 891–897 (1999).

Schulting, R. J. & Richards, M. P. Antiquity 76, 1011–1025 (2002).

Tauber, H. Nature 292, 332–333 (1981).

Richards, M. P., Price, T. D. & Koch, E. Curr. Anthropol. 44, 288–294 (2003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

brief communications is intended to provide a forum for brief, topical reports of general scientific interest and for technical discussion of recently published material of particular interest to non-specialist readers (communications arising). Priority will be given to contributions that have fewer than 500 words, 10 references and only one figure. Detailed guidelines are available on Nature's website (http://www.nature.com/nature).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Richards, M., Schulting, R. & Hedges, R. Sharp shift in diet at onset of Neolithic. Nature 425, 366 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/425366a

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/425366a

This article is cited by

-

Multiproxy bioarchaeological data reveals interplay between growth, diet and population dynamics across the transition to farming in the central Mediterranean

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Human consumption of seaweed and freshwater aquatic plants in ancient Europe

Nature Communications (2023)

-

A multi-isotope analysis on human and pig tooth enamel from prehistoric Sichuan, China, and its archaeological implications

Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences (2022)

-

Marine resource abundance drove pre-agricultural population increase in Stone Age Scandinavia

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Continuation of fishing subsistence in the Ukrainian Neolithic: diet isotope studies at Yasinovatka, Dnieper Rapids

Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.