Abstract

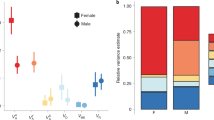

To appreciate how new morphological traits arise in the course of evolution, we need to understand both the genetic basis of phenotypic changes and the selective forces that promote them. We presented evidence that evolutionary changes in the regulation of the bab gene could account for the origin of sexually dimorphic abdominal pigmentation in D. melanogaster; we also investigated whether sexual selection could explain the origin and maintenance of this trait.

Similar content being viewed by others

Kopp et al. reply

We found that, given a choice between wild-type and bab-mutant females (which have ectopic male-like pigmentation), D. melanogaster males discriminated in favour of normally pigmented females. This effect was observed in several combinations of bab-mutant and wild-type strains, but was abolished when white-mutant males, which are effectively blind, were used in mate-choice experiments. On this basis, we suggested that sexual selection against darkly pigmented females can account for the maintenance of sexual dimorphism.

However, Llopart et al. argue that this mechanism is unlikely to operate in nature. The difference between our findings is presumably due to the choice of model fly strains. As Llopart et al. point out, both the males and females used in our experiments were derived from highly inbred laboratory strains, and extrapolation to natural populations seems not to be supported.

The questions remain –– why did male-specific pigmentation evolve in D. melanogaster but not in other Drosophila lineages? Why is it absent in females? And what selective pressure has maintained this dimorphism for over 20 million years? For now, the answers are that we do not know.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kopp, A., Carroll, S. Pigmentation and mate choice in Drosophila. Nature 419, 360 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/419360b

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/419360b

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.