Abstract

There is an emerging consensus that genomic researchers should, at a minimum, offer to return to individual participants clinically valid, medically important and medically actionable genomic findings (for example, pathogenic variants in BRCA1) identified in the course of research. However, this is not a common practice in psychiatric genetics research. Furthermore, psychiatry researchers often generate findings that do not meet all of these criteria, yet there may be ethically compelling arguments to offer selected results. Here, we review the return of results debate in genomics research and propose that, as for genomic studies of other medical conditions, psychiatric genomics researchers should offer findings that meet the minimum criteria stated above. Additionally, if resources allow, psychiatry researchers could consider offering to return pre-specified ‘clinically valuable’ findings even if not medically actionable—for instance, findings that help corroborate a psychiatric diagnosis, and findings that indicate important health risks. Similarly, we propose offering ‘likely clinically valuable’ findings, specifically, variants of uncertain significance potentially related to a participant’s symptoms. The goal of this Perspective is to initiate a discussion that can help identify optimal ways of managing the return of results from psychiatric genomics research.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Visscher PM, Brown MA, McCarthy MI, Yang J . Five years of GWAS discovery. Am J Hum Genet 2012; 90: 7–24.

Sullivan PF, Daly MJ, O’Donovan M . Genetic architectures of psychiatric disorders: the emerging picture and its implications. Nat Rev Genet 2012; 13: 537–551.

Schizophrenia Psychiatric Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) Consortium. Genome-wide association study identifies five new schizophrenia loci. Nat Genet 2011; 43: 969–976.

Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 2014; 511: 421–427.

Need AC, Goldstein DB . Schizophrenia genetics comes of age. Neuron 2014; 83: 760–763.

McCarroll SA, Feng G, Hyman SE . Genome-scale neurogenetics: methodology and meaning. Nat Neurosci 2014; 17: 756–763.

Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Genetic relationship between five psychiatric disorders estimated from genome-wide SNPs. Nat Genet 2013; 45: 984–994.

Yuen RKC, Mericio D, Bookman M, Howe JL, Thiruvahindrapuram B, Patel RV et al. Whole genome sequencing resource identifies 18 new candidate genes for autism spectrum disorder. Nat Neurosci 2017; 20: 602–611.

Berg JS, Adams M, Nassar N, Bizon C, Lee K, Schmitt CP et al. An informatics approach to analyzing the incidentalome. Genet Med 2013; 15: 36–44.

Berg JS, Foreman AK, O'Daniel JM, Booker JK, Boshe L, Carey T et al. A semiquantitative metric for evaluating clinical actionability of incidental or secondary findings from genome-scale sequencing. Genet Med 2016; 18: 467–475.

Petrucelli N, Daly MB, Pal T . BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Stephens K, Amemiya A, Ledbetter N (eds). GeneReviews [Internet]. University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 2016. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1247/. accessed 17 May 2017.

Warby SC, Graham RK, Hayden MR . Huntington disease. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Stephens K, Amemiya A, Ledbetter N (eds). GeneReviews [Internet]. University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 2014. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1305/, accessed 17 May 2017.

Bird TD . Early-onset familial Alzheimer disease. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Stephens K, Amemiya A, Ledbetter N (eds). GeneReviews [Internet]. University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 2012. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1236/, accessed May 17, 2017.

Sullivan PF, Agrawal A, Bulik CM, Andreassen OA, Borglum A, Breen G et al. Psychiatric genomics: an update and an agenda. American Journal of Psychiatry; doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17030283 [e-pub ahead of print].

National Human Genome Research Institute. DNA sequencing costs: data, 2016. Available at https://www.genome.gov/sequencingcostsdata/, accessed 17 May 2017.

Petrone J . New Illumina SNP array fuels European Consortium founded to foment 'Third Generation GWAS Era'. GenomeWeb, Available at https://www.genomeweb.com/microarrays-multiplexing/new-illumina-snp-array-fuels-european-consortium-founded-foment-third. Accessed on 15 June 2016.

Genovese G, Fromer M, Stahl EA, Ruderfer DM, Chambert K, Landen M et al. Increased burden of ultra-rare protein-altering variants among 4,877 individuals with schizophrenia. Nat Neurosci 2016; 19: 1433–1441.

Berland LL, Silverman SG, Gore RM, Mayo-Smith WW, Megibow AJ, Yee J et al. Managing incidental findings on abdominal CT: White Paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee. J Am Coll Radiol 2010; 7: 754–773.

Munk MD, Peitzman AB, Hostler DP, Wolfson AB . Frequency and follow-up of incidental findings on trauma computed tomography scans: Experience at a level one trauma center. J Emerg Med 2010; 38: 346.

Wolf SM, Lawrenz FP, Nelson CA, Kahn JP, Cho MK, Clayton EW et al. Managing incidental findings in human subjects research: analysis and recommendations. J Law Med Ethics 2008; 36: 19–48.

Illes J, Kirschen MP, Edwards E, Stanford LR, Bandettini P, Cho MK et al. Incidental findings in brain imaging research. Science 2006; 311: 783–784.

Ross LF, Rothstein MA, Clayton EW . Mandatory extended searches in all genome sequencing: ‘incidental findings,’ patient autonomy, and shared decision making. JAMA 2013; 310: 367–368.

Klitzman R, Appelbaum PS, Chung W . Return of secondary genomic findings vs patient autonomy: implications for medical care. JAMA 2013; 310: 369–370.

Kohane IS, Masys DR, Altman RB . The incidentalome: a threat to genomic medicine. JAMA 2006; 296: 212–215.

Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues. Anticipate and communicate: ethical management of incidental and secondary findings in the clinical, research, and direct-to-consumer contexts. Available at http://bioethics.gov/sites/default/files/FINALAnticipateCommunicate_PCSBI_0.pdf, accessed 17 May 2017 2013.

Allyse M, Michie M . Not-so-incidental findings: the ACMG recommendations on the reporting of incidental findings in clinical whole genome and whole exome sequencing. Trends Biotechnol 2013; 31: 439–441.

Jarvik GP, Amendola LM, Berg JS, Brothers K, Clayton EW, Chung W et al. Return of genomic results to research participants: the floor, the ceiling, and the choices in between. Am J Hum Genet 2014; 94: 818–826.

Shalowitz DI, Miller FG . Disclosing individual results of clinical research: implications of respect for participants. JAMA 2005; 294: 737–740.

Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW, Kalia SS, Korf BR, Martin CL et al. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet Med 2013; 15: 565–574.

McGuire AL, Knoppers BM, Zawati MH, Clayton EW . Can I be sued for that? Liability risk and the disclosure of clinically significant genetic research findings. Genome Res 2014; 24: 719–723.

Bredenoord AL, Kroes HY, Cuppen E, Parker M, van Delden JJM . Disclosure of individual genetic data to research participants: the debate reconsidered. Trends Genet 2011; 27: 41–47.

Appelbaum PS, Roth LH, Lidz C . The thereapeutic misconception: informed consent in psychiatric research. Int J Law Psychiatry 1982; 5: 319–329.

Meltzer LA . Undesirable implications of disclosing individual genetics results to research participants. Am J Bioeth 2006; 6: 28–30.

Evans J . Finding common ground. Genet Med 2013; 15: 852–853.

Klitzman R, Appelbaum PS, Fyer A, Martinez J, Buquez B, Wynn J et al. Researchers’ views on return of incidental genomic results: qualitative and quantitative findings. Genet Med 2013; 15: 888–895.

Klitzman R, Chung W, Marder K, Shanmugham A, Chin LJ, Stark M et al. Attitudes and practices among internists concerning genetic testing. J Genet Couns 2013; 22: 99–100.

Finn CT, Wilcox MA, Korf BR, Blacker D, Racette SR, Sklar P et al. Psychiatric genetics: a survey of psychiatrists' knowledge, opinions, and practice patterns. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66: 821–830.

Hoop JG, Roberts LW, Hammond KA, Cox NJ . Psychiatrists' attitudes, knowledge, and experience regarding genetics: a preliminary study. Genet Med 2008; 10: 439–449.

Klitzman R, Abbate KJ, Chung WK, Marder K, Ottman R, Taber KJ et al. Psychiatrists’ views of the genetic bases of mental disorders and behavioral traits and their use of genetic tests. J Nerv Ment Dis 2014; 202: 530–538.

Ravitsky V, Wilfond BS . Disclosing individual genetic results to research participants. Am J Bioeth 2006; 6: 8–17.

Kohlman W, Gruber SB Lynch syndrome. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Stephens K, Amemiya A, Ledbetter N (eds). GeneReviews® [Internet]. University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 2014. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1211/, accessed 17 May 2017.

National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The Belmont Report: ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research, 1979. Available at https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/.

The Nuremberg Code. in: Trials of war criminals before the Nuremberg military tribunals under control council law No. 10, vol.2, US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, 1949, pp. 181–182. Available at https://history.nih.gov/research/downloads/nuremberg.pdf.

World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving subjects. JAMA 2013; 310: 2191–2194.

Beauchamp TL, Childress JF . Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 7th ed. University Press: New York, 2012.

Fernandez CV, Kodish E, Weijer C . Informing study participants of research results: an ethical imperative. IRB 2003; 25: 12–19.

Foster MW, Sharp RR . Ethical issues in medical-sequencing research: implications of genotype-phenotype studies for individuals and populations. Hum Mol Genet 2006; 15: R45–R49.

Quaid KA, Jessup NM, Meslin EM . Disclosure of genetic information obtained through research. Genet Test 2004; 8: 347–355.

Bredenoord AL, Onland-Moret NC, Van Delden JJM . Feedback of individual genetic results to research participants: in favor of a qualified disclosure policy. Hum Mutat 2011; 32: 861–867.

Hoeyer K . Donors perceptions of consent to and feedback from biobank research: time to acknowledge diversity? Public Health Genomics 2010; 13: 345–352.

Kaufman D, Murphy J, Scott J, Hudson K . Subjects matter: a survey of public opinions about a large genetic cohort study. Genet Med 2008; 10: 831–839.

Kaufman DJ, Baker R, Milner LC, Devaney S, Hudson KL . A survey of U.S adults' opinions about Conduct of a Nationwide Precision Medicine Initiative® cohort study of genes and environment. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0160461.

Murphy J, Scott J, Kaufman D, Geller G, LeRoy L, Hudson K . Public expectations for return of results from large-cohort genetic research. Am J Bioeth 2008; 8: 36–43.

Ramoni RB, McGuire AL, Robinson JO, Morley DS, Plon SE, Joffe S . Experiences and attitudes of genome investigators regarding return of individual genetic test results. Genet Med 2013; 15: 882–887.

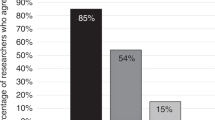

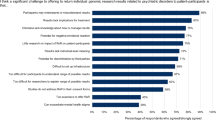

Middleton A, Morley KI, Bragin E, Firth HV, Hurles ME, Wright CF et al. Attitudes of nearly 7000 health professionals, genomic researchers and publics toward the return of incidental results from sequencing research. Eur J Hum Genet 2016; 24: 21–29.

National Bioethics Advisory Committee Research involving human biological materials: Ethical issues and policy guidance vol. 1. National Bioethics Advisory Committee: Rockville, MD, 1999.

Bookman EB, Langehorne AA, Eckfeldt JH, Glass KC, Jarvik GP, Klag M et al. Reporting genetic results in research studies: summary and recommendations of an NHLBI working group. Am J Med Genet A 2006; 140: 1033–1040.

National Human Genome Research Institute. NHGRI Policy Recommendations on Research Privacy Guidelines: Federal Policy Recommendations on Including HIPAA, 2012. Available at https://www.genome.gov/11510216/, accessed 17 May 2017.

Collins FS, Varmus H . A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 793–795.

Genomics England. Results. Available at https://www.genomicsengland.co.uk/taking-part/information-for-participants/results/, accessed 17 May 2017.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group, Fabsitz RR, McGuire A, Sharp RR, Puggal M, Beskow LM et al. Ethical and practical guidelines for reporting genetic research results to study participants: updated guidelines from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2010; 3: 574–580.

Parliament of Finland. Biobank Act 688/2012. Finland Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, 2012. Available at http://www.finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/2012/en20120688.pdf, accessed 2 June 2017.

Parliament of Estonia. Human Genes Research Act. 2000, Available at https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/531102013003/consolide, accessed 2 June 2017.

Ministry of Education C, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Ministriy of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW), and Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry (METI) Ethical guidelines for human genome/gene analysis research (2001). Fully revised in 2004 and 2013, partially revised in 2005 and 2008.

H3Africa Working Group on Ethics and Retulatory Issues for the Human Heredity and Health (H3Africa) Consortium. H3Africa guidelines for informed consent. 2013, Available at http://www.health.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/116/H3Africa. Guidelines on Informed Consent August 2013.pdf, accessed 2 June 2017.

Indian Council of Medical Research. Ethical guidelines for biomedical research on human participants. 2006, Available at http://icmr.nic.in/ethical_guidelines.pdf, accessed 2 June 2017.

Knoppers BM, Zawati MH, Sénécal K . Return of genetic testing results in the era of whole-genome sequencing. Nat Rev Genet 2015; 16: 553–559.

Parliament of Spain. Law 14/2007, of 3 July, on Biomedical Research, 2000. Available at http://www.isciii.es/ISCIII/es/contenidos/fd-investigacion/SpanishLawonBiomedicalResearchEnglish.pdf, accessed 2 June 2017.

The Bioethics Advisory Committee Singapore. Ethical, legal and social issues in genetic testing and genetics research, 2005. Available at http://www.bioethics-singapore.org/images/uploadfile/21929 PMGT CP Final.pdf, accessed 2 June 2017.

Danish Council of Ethics. Genome testing: ethical dilemmas in relation to diagnostics, research and direct-to-consumer testing. 2012, Available at http://www.etiskraad.dk/~/media/Etisk-Raad/en/Publications/Genome-testing-report-2012.pdf?la=da, accessed 2 June 2017.

Parliament of Taiwan. Human Biobank Management Act. 2012. Available at http://law.moj.gov.tw/Eng/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?PCode=L0020164, accessed 2 June 2017.

Evans JP, Berg JS, Olshan AF, Magnuson T, Rimer B . We screen newborns, don’t we?: realizing the promise of public health genomics. Genet Med 2013; 15: 332–334.

Weiss KH . Wilson disease. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Stephens K, Amemiya A, Ledbetter N (eds). GeneReviews® [Internet]. University of Washington: Seattle, WA, 2016. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1512/, accessed 17 May 2017.

American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. ACMG practice guidelines: incidental findings in clinical genomics: a clarification. Genet Med 2013; 15: 664–666.

McGuire AL, Joffe S, Koenig BA, Biesecker BB, McCullough LB, Blumenthal-Barby JS et al. Ethics and genomic incidental findings. Science 2013; 340: 1047–1048.

Wolf SM, Annas GJ, Elias S . Patient autonomy and incidental findings in clinical genomics. Science 2013; 340: 1049–1050.

Burke W, Antommaria AH, Bennet R, Botkin J, Clayton EW, Henderson GE et al. Recommendations for returning genomic incidental findings? We need to talk!. Genet Med 2013; 15: 855–859.

American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. ACMG updates recommendation on ‘opt out’ for genome sequencing return of results, 2014. Available at https://www.acmg.net/docs/Release_ACMGUpdatesRecommendations_final.pdf.

Kalia SS, Adelman K, Bale SJ, Chung WK, Eng C, Evans JP et al. Recommendations for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, 2016 update (ACMG SF v2. 0): A policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med 2017; 19: 249–255.

Geisinger Health System. Geisinger Health System list of clinically actionable genes for the Mycode Community Health Initiative. Available at https://www.geisinger.org/-/media/OneGeisinger/Images/GHS/Research/CentersandInstitutes/ClinicallyActionableGenes.ashx?la=en, accessed 8 June 2017.

Berg JS, Khoury MJ, Evans JP . Deploying whole genome sequencing in clinical practice and public health: meeting the challenge one bin at a time. Genet Med 2011; 13: 499–504.

Berg JS, Amendola LM, Eng C, Van Allen E, Gray W, Wagle N et al. Processes and preliminary outputs for identification of actionable genes as incidental findings in genomic sequence data in the Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research Consortium. Genet Med 2013; 15: 860–867.

Lu Y, Pouget JG, Andreassen OA, Djurovic S, Esko T, Hansen T et al. Genetic risk scores and family history as predictors of schizophrenia in Nordic registers. Psychol Med 2017; 1–9; doi: 10.1017/S0033291717002665 [e-pub ahead of print].

Lázaro-Muñoz G . The fiduciary relationship model for managing clinical genomic ‘incidental’ findings. J Law Med Ethics 2014; 42: 576–589.

Lázaro-Muñoz G, Conley JM, Davis AM, Van Riper M, Walker RL, Juengst ET . Looking for trouble: preventive genomic sequencing in the general population and the role of patient choice. Am J Bioeth 2015; 15: 3–14.

Appelbaum PS, Parens E, Waldman CR, Klitzman R, Fyer A, Martinez J et al. Models of consent to return incidental findings in genomic research. Hastings Cent Rep 2014; 44: 22–32.

Regier DA, Peacock SJ, Pataky R et al. Societal preferences for the return of incidental findings from clinical genomic sequenicng: a discrete-choice experiment. CMAJ 2015; 187 (6): E190–E197.

Federal Register. Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, 82 Fed. Reg. 7149, 7221 (19 January 2017).

Fullerton SM, Wolf WA, Brothers KB, Clayton EW, Crawford DC, Denny JC et al. Return of individual research results from genome-wide association studies: experience of the Electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE) Network. Genet Med 2012; 14: 424–431.

Goddard KA, Whitlock EP, Berg JS, Williams MS, Webber EM, Webster JA et al. Description and pilot results from a novel method for evaluating return of incidental findings from next generation sequencing technologies. Genet Med 2013; 15: 721–728.

Lázaro-Muñoz G, Conley JM, Davis AM, Prince AE, Cadigan RJ . Which results to return: subjective judgments in selecting medically actionable genes. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 2017; 21: 184–194.

Vassos E, Collier DA, Holden S . Penetrance for copy number variants associated with schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet 2010; 19: 3477–3481.

Kirov G, Rees E, Walters JTR, Escott-Price, Georgieva L, Richards AL et al. The penetrance of copy number variants for schizophrenia and developmental delay. Biol Psychiatry 2014; 75: 378–385.

Kocarnik JM, Fullerton SM . Returning pleiotropic results from genetic testing to patients and research participants. JAMA 2014; 311: 795–796.

McDonald-McGinn DM, Emanuel BS, Zackai EH 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Stephens K, Amemiya A, Ledbetter N (eds). GeneReviews® [Internet]. University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 2013. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1523/, accessed 17 May 2017.

Patterson M Niemman–Pick disease type C. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Stephens K, Amemiya A, Ledbetter N (eds) GeneReviews® [Internet]. University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 2013. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1296/, accessed 17 May 2017.

International Society for Psychiatric Genomics. Genetic testing statement, 2017. https://ispg.net/genetic-testing-statement/, accessed 17 May 2017.

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 2015; 17: 405–424.

Budin-Ljøsne I, Mascalzoni D, Soini S, Machado H, Kaye J, Bentzen HB et al. Feedback of individual genetic results to research participants: is it feasible in Europe? Biopreserv Biobank 2016; 14: 241–248.

Clinical Laboratory Improvements Act of 1988, Pub. L. No. 100-578, 102 Stat. 2903; see regulations at 42 CFR 493(b)2.

Finn CT . Increasing genetic education for psychiatric residents. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2007; 15: 30–33.

Hoop JG, Savla G, Roberts LW, Zisook S, Dunn LB . The current state of genetics training in psychiatric residency: Views of 235 U.S. Educators and Trainees. Acad Psychiatry 2010; 34: 109–114.

Genes for Good. Learning about your genome, 2017. Available at https://genesforgood.sph.umich.edu/return_of_results/ancestry, accessed 25 September 2017.

Jamal L, Robinson JO, Christensen KD, Blumenthal-Barby J, Slashinski MJ, Perry DL et al. When bins blur: Patient perspectives on categories of results from clinical whole genome sequencing. AJOB Empir Bioeth 2017; 8: 82–88.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Maria D. Iglesias de Ussel, Eric T. Ward, Genna Finkel, Jonathan S. Berg and James P. Evans for helpful work and discussions about the topics addressed in this paper. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful observations. Research for this article was funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R00HG008689 (Lázaro-Muñoz, G).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

PF Sullivan reports the following potentially competing financial interests: Element Genomics (Scientific Advisory Board member, stock options), Lundbeck (advisory committee), Pfizer (Scientific Advisory Board member) and Roche (grant recipient, speaker reimbursement). The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lázaro-Muñoz, G., Farrell, M., Crowley, J. et al. Improved ethical guidance for the return of results from psychiatric genomics research. Mol Psychiatry 23, 15–23 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.228

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.228

This article is cited by

-

Disclosure of clinically actionable genetic variants to thoracic aortic dissection biobank participants

BMC Medical Genomics (2021)

-

“It’s all about delivery”: researchers and health professionals’ views on the moral challenges of accessing neurobiological information in the context of psychosis

BMC Medical Ethics (2021)

-

Ethical issues in genomics research on neurodevelopmental disorders: a critical interpretive review

Human Genomics (2021)

-

Perceptions of best practices for return of results in an international survey of psychiatric genetics researchers

European Journal of Human Genetics (2021)

-

Psychosis, vulnerability, and the moral significance of biomedical innovation in psychiatry. Why ethicists should join efforts

Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy (2020)