Abstract

As the human papillomavirus (HPV)-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma epidemic has developed in the past several decades, it has become clear that these tumors have a wide variety of morphologic tumor types and features. For the practicing pathologist, it is critical to have a working knowledge about these in order to make the correct diagnosis, not to confuse them with other lesions, and to counsel clinicians and patients on their significance (or lack of significance) for treatment and outcomes. In particular, there are a number of pitfalls and peculiarities regarding HPV-related tumors and their nodal metastases that can easily result in misclassification and confusion. This article will discuss the various morphologic types and features of HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinomas, specific differential diagnoses when challenging, and, if established, the clinical significance of each finding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

It is now well-established that human papillomavirus (HPV) is responsible for a large fraction of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (SCC), particularly in the United States and Europe.1 Many have termed the increase in HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC as an epidemic.2, 3 There are numerous clinical, biological, epidemiological, molecular, and morphologic features that are unique to these tumors,4, 5, 6 such that it is almost misleading to term it as a variant of head and neck SCC. It is probably more accurate to think of these as completely unique tumors, in a category of their own. Most major publications, textbooks, and practice guidelines now clearly separate oropharyngeal from oral (and other anatomic subsite) SCCs, and staging systems are beginning to differentiate HPV-related tumors from others. These are all reflections of the growing appreciation of the differences in biology, morphology, and clinical features.

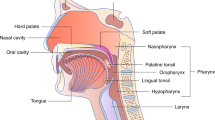

Among its many effects on clinical practice, the oropharyngeal HPV epidemic has put pathologists at the forefront of diagnosis and recognition of these unique tumors, which are much less clinically aggressive than conventional head and neck SCC, and which are beginning to be managed differently.7 Tumor morphology in HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC is diverse,8, 9 interesting, and unique amongst head and neck tumors (Table 1), partially because of the peculiar anatomy of the oropharynx, and partially because of the way HPV-related oropharyngeal SCCs begin in the tonsillar crypts, spread to the neck nodes, and progress once they have metastasized. There are a number of diagnostic pitfalls because of unusual morphology, actually. HPV-related SCCs can look poorly differentiated even in their most prognostically favorable forms, metastasis-capable lesions can look like in situ carcinoma, cystic nodal metastases can mimic benign cysts including the occasional presence of cilia, and oropharyngeal small-cell carcinomas can look very much like SCCs.9, 10 Slight misinterpretations of the morphologic features and their significance are commonplace in current surgical pathology practice. Much like the Frank Abagnale character, who in real life and in the play and movie Catch Me If You Can mimicked many different people and professions he knew almost nothing about, HPV-related carcinomas frequently appear under the microscope as something very different than what they are. Our job as pathologists then is similar to the detective Carl Hanratty: solve the mystery and recognize the imposter for what it really is. This article will discuss the various morphologic types and features of HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinomas, the corresponding differential diagnoses, and, if established, the clinical significance of each finding.

Discussion

Common Morphologic Types of SCC

HPV-related SCCs arise from the reticulated tonsillar crypt epithelium, which is an irregular mucosa which has lymphocytes and basal-appearing squamous cells tightly overlapping and interconnected.11 The squamous cells of this epithelium, particularly in its basal aspects, are immature appearing, with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios and oval nuclei, devoid of nucleoli and showing relatively prominent mitotic activity (Figure 1a). It is perhaps not surprising, then, that most HPV-related oropharyngeal SCCs also have an immature, ‘basal’ appearance. This was first described in the early 2000 s and was variably termed ‘basaloid’, ‘poorly differentiated’, ‘with basal cell features’, or ‘nonkeratinizing.’

Normal reticulated tonsillar crypt epithelium and the most common morphologic types of HPV-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). (a) Reticulated tonsillar crypt epithelium (× 40) (b) Nonkeratinizing SCC (× 10) (c) Nonkeratinizing SCC with maturation (× 10) (d) Keratinizing SCC (× 10).

Over the years, this has been greatly clarified by typing of the tumors into nonkeratinizing, nonkeratinizing with maturation, and keratinizing (or conventional) types.8, 12, 13 Nonkeratinizing SCC consists of submucosal and lobulated tumor with large nests that typically have smooth edges, a haphazard arrangement, and little stromal reaction. The tumor cells have indistinct cell borders, small to modest amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm, and oval to spindled nuclei which are hyperchromatic and lack (or have inconspicuous) nucleoli (Figure 1a). There is brisk mitotic activity and abundant apoptosis. Comedo-type necrosis is also common. Maturing squamous differentiation, characterized by polygonal cells with mature, eosinophilic cytoplasm, distinct cell borders, intercellular bridges, and keratin pearls, is frequently absent, or, if present, is limited (by definition <10% of the tumor surface area). Keratinizing, or conventional, SCC (Figure 1c) is exactly that seen throughout the upper aerodigestive tract. These tumors are composed of irregular, angulated sheets and nests of tumor with infiltrative borders, usually with prominent desmoplastic stromal response. The tumor cells are polygonal with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, prominent cell borders and frequently have intercellular bridges. True keratin formation is common, but does not have to be present, as ‘keratinizing’ refers to the dense cytoplasmic eosinophilia imparted by keratin intermediate filaments. Such tumors can range from well to poorly differentiated. Non-keratinizing SCC with maturation is an intermediate group that consists of definitive nonkeratinizing areas but that also has maturing squamous differentiation comprising >10% of tumor surface area. The squamous differentiation is characteristically located aberrantly at the periphery of the nests (‘reverse maturation’; Figure 1d), and there is often artifactual clefting around the nests, similar to that seen in basal cell carcinomas of the skin.13, 14

Although several studies have correlated morphologic features with high risk HPV status (or p16 immunohistochemical status as a surrogate marker of HPV), showing that tumors termed ‘basaloid’, ‘poorly differentiated’, or ‘basal’ are much more likely to be HPV-related and are prognostically favorable in the oropharynx, nonkeratinizing SCC, in particular, has been shown to be essentially always related to transcriptionally-active high risk HPV. In a large, four year study of routine practice with 435 total patients,8 nonkeratinizing SCC constituted 53% of all tumors and 226 of the 228 patients were p16 positive. Of the two p16-negative patients, one could be tested for HPV and by RT-PCR it was positive for high-risk HPV E6/E7 mRNA. Nonkeratinizing SCC with maturation was usually HPV-related as well (~92%). All p16-positive nonkeratinizing pattern tumors were positive for high risk HPV mRNA by RT-PCR.

Several pitfalls exist here in practice. First, although nonkeratinizing SCCs look poorly differentiated, they are molecularly less complex and clinically more favorable than keratinizing (conventional) SCCs because they are HPV positive.9, 15 So differentiation status, in the classic sense and definitions for head and neck SCC, is not only not indicated, it can be confusing to the clinician because the most poorly differentiated looking tumors are the best ones. It is likely, although unproven, that these tumors are differentiating into the immature appearing tonsillar crypt epithelial type squamous cells which, as mentioned before, are immature looking.11 Finally, one cannot assume that at the other end of the spectrum, keratinizing SCC should be unrelated to HPV. In fact, a small fraction of such tumors (~15–25%), are transcriptionally–active HPV positive. The best available data suggests that these patients have the same favorable prognosis as those with tumors that are nonkeratinizing. As such, the molecular (HPV) status trumps the morphology when it comes to prognosis.12, 16

The differential diagnosis for nonkeratinizing SCC includes small-cell carcinoma and basaloid SCC. Small-cell carcinoma, as will be discussed later, is a high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma, with histologic features identical to those in the lung. Recent studies have shown that the majority of small-cell carcinomas of the oropharynx are related to transcriptionally active high-risk HPV but, unlike SCC, do not seem to have a more favorable prognosis due to the presence of the virus.17, 18, 19 Keys to recognizing them are the very high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios of the cells and angulated or tapered nuclei with speckled chromatin and nuclear molding. These can be only very subtly different from nonkeratinizing SCC, as both have high N:C ratios and apoptosis, mitosis, and necrosis. Seeing squamous differentiation does not rule out small-cell carcinoma as they can be mixed with SCC.20 A low threshold for immunohistochemistry, with a panel of p40, synaptophysin, chromogranin, and cytokeratin 5/6, is recommended.

Basaloid SCC, although the name sounds similar to nonkeratinizing SCC and both have ‘basal’ appearing nuclei, is a distinct form of head and neck SCC. It should have a very pronounced form of tight nesting with rounded edges, a jigsaw puzzle pattern where the nests ‘mold’ to themselves, and hyalinized basement membrane material in and around the nests. Nuclei are round, and necrosis and basophilic myxoid stroma are common.21 In the oropharynx, most are related to transcriptionally active high-risk HPV.22, 23 Interestingly, in the oropharynx, it is common to have basaloid SCC areas mixed with nonkeratinizing SCC or even with keratinizing SCC.

Anaplasia and Multinucleation

One peculiar feature of HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC is that some tumors have marked nuclear heterogeneity with the presence of eye-popping nuclear pleomorphism or numerous multinucleated cells.15 This is often focal or multifocal in the tumors and rarely diffuse.24 Scattered single anaplastic or multinucleated cells can be seen, but the single definition applied in the literature to date requires at least three anaplastic nuclei (>4 lymphocyte nuclei wide or >~25 microns) or three overtly multinucleated tumor cells in one high-power field (Figure 2).24 The single study24 of surgical resection specimens showed anaplasia and/or multinucleation in 50–60% of patients, and disease specific survival was worse in multivariate analysis. Patients with these changes had better prognosis than HPV-negative tumor patients, but ~10 to 12 times higher likelihood of dying of their cancers than those patients lacking the features. Further, of the patients who lack the changes, almost no one died of their disease. Further study is warranted to validate these for possible use in routine practice.

Tonsillar Crypt Carcinoma (In Situ vs Invasive)

HPV-related SCCs tend to present clinically in different ways than other head and neck cancers. In particular, they very frequently have nodal metastases at presentation (as high as 80–85% of patients),3, 25 while having higher rates of T1 and T2 tumors than HPV-negative SCC and.1, 26, 27 The reason for this has not clearly been established, but some unusual anatomic features of the tonsillar tissue of the oropharynx provide some clues. HPV is tropic for tonsillar tissue, in particular, the reticulated tonsillar crypt epithelium (Figure 1a). This epithelium consists of irregular, drawn out invaginations of squamous mucosa with increased numbers of basal appearing cells intimately admixed with lymphocytes and with the organized lymphoid tissue of the oropharynx (specifically the palatine tonsils and base of tongue). Electron microscopy studies of this epithelium have revealed that the basement member is discontinuous and further, that there are intraepithelial capillaries.11, 15 Biopsies of tumors and even full resections of small tumors frequently show what histologically appears to be nonkeratinizing SCC in situ (Figure 3), even in the face of known nodal metastases. This is likely because the tonsillar crypt epithelium is a poor barrier to spread, rather than a function of tumor aggressiveness.15, 28 HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC frequently grows along the surface of the tonsillar crypts without stromal reaction or obvious tumor infiltration or stromal reaction.9, 15, 28 As one cannot tell histologically what is just localized versus metastasis capable tumor, the term in situ carcinoma of the tonsillar crypt epithelium should not be used. Rather, the simple term ‘squamous cell carcinoma’ should be used in this situation without reference to invasive or not.15, 28

Other Histologic Variants of SCC

Although most HPV-related oropharyngeal SCCs have a nonkeratinizing morphology, these constitute only approximately 80–85% of all tumors.8 Numerous other histologic variants of SCC occur in the oropharynx.22, 23, 29, 30, 31, 32

Basaloid SCC, as previously mentioned, and its most strict form, consists of a very blue looking tumor with large, rounded nests with a jigsaw puzzle pattern of growth, hyalinized basement membrane material in thin lines between the nests and in nodules, foci of comedo necrosis, and often myxoid material (Figure 4a).21 These constitute ~3% of all oropharyngeal SCC,8 and approximately 80–90% are transcriptionally active high-risk HPV positive.22, 23 Nonkeratinizing SCC, in contrast, tends to have larger nests that are more irregular and haphazard. Tumor cells are often more oval or spindled rather than round, and there is no hyalinized basement membrane-like material.14

Papillary SCC is also a major histologic variants in the oropharynx (also ~3%).8, 29, 30 Although definitions vary somewhat, the WHO classifies these as papillary if they are predominantly composed of tumor cells on delicate papillae, thus many require at least 50% papillary growth.33 Tumors should consist of full-thickness dysplastic squamous cells, and most of the time these are nonkeratinizing in appearance with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios and brisk mitotic activity (Figure 4b). The literature shows that ~75 to 80% of papillary SCC are transcriptionally active high-risk HPV positive.29, 30

Lymphoepithelial (or undifferentiated) carcinoma occurs in the oropharynx (approximately 2–3%).8 It has a morphology identical to that seen in nasopharyngeal undifferentiated carcinoma, with sheets or sometimes singly dispersed tumor cells in a dense lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 4c). Tumor cells classically have a syncytial appearance with ill defined cell borders and only modest amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm. The nuclei are classically vesicular with thick nuclear membranes and prominent single macro nucleoli. These can be very subtle, mixed in with the background lymphoid tissue of the tonsil and base of tongue. Between 95 and 100% of such tumors in the oropharynx are transcriptionally active high-risk HPVpositive.32, 34 In the oropharynx, they are not related to Epstein–Barr virus.32, 34

Other SCC variants occur in the oropharynx, but they are much less common. Adenosquamous carcinomas have punched out glandular spaces, usually with associated mucin production, but mixed with areas of typical SCC (Figure 4d).35 Very few cases of adenosquamous carcinoma of the oropharynx have been tested for high risk HPV so no reliable fraction is known. However, the few cases have been ~50% HPV-related.8, 36 Spindle cell carcinomas are very uncommon in the oropharynx, but rare transcriptionally active HPV-positive tumors have been reported.37, 38 Verrucous carcinomas are extremely rare in the oropharynx and literature suggests that essentially none of the verrucous carcinomas anywhere in the head and neck are related to transcriptionally active HPV.39, 40 The best evidence available, and the data are somewhat limited by small numbers of patients, strongly suggests that all types of oropharyngeal SCC, including the variants, when associated with transcriptionally active high-risk HPV, have the same favorable prognosis.22, 23, 29, 30, 32, 34, 36

Cystic Nodal Metastases and Ciliated Cells

Nodal metastases are very frequent and HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC, occurring in as many as 80–85% of patients at presentation.25 We have previously discussed how the reticulated tonsillar crypt epithelium appears to be a poor barrier to the spread of these tumors due to its unique anatomy. A common finding in these nodal metastases is cystic change. This has been documented in many different studies, by clinical, radiographic, and pathologic analysis.41 Although non-HPV-related metastatic squamous cell carcinomas can be cystic and necrotic, marked cystic change with thin walls to the nodal metastases is very highly associated with HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC (Figure 5). Further, the vast majority of the cystic lymph node metastases from HPV-related SCC have a nonkeratinizing appearance. The lining tumor cells can range from extremely thin to an almost single layer with a relatively bland appearance to having markedly thick walls with hyperchromatic and vary angulated and jumbled appearing cells with small nests of tumor cells in the adjacent nodal tissue. Nodal metastases with cystic change can be a source of great confusion and difficulty for several reasons.

Since many patients present due to their neck masses for metastatic SCC, and since primary tumors are often very small or are completely clinically occult (cancer of unknown primary or CUP),42 tissue sampling of the cystic lymph nodes is often required. This is frequently by fine-needle aspiration, and there is a low but non-negligible false-negative rate due to aspirating only cyst contents with degenerating squamous cells.43, 44, 45 In addition, as p16 immunohistochemistry is being used more frequently on cell block preparations from neck lymph node metastasis fluid, one has to be careful because degenerating squamous cells can lose their reactivity, again resulting in not a false negative malignancy diagnosis, but a false negative results for this surrogate marker of transcriptionally active HPV. A few recent studies on neck lymph node fine-needle aspiration patients has demonstrated this, fortunately uncommon, phenomenon.43, 44, 45

Another confusing aspect to cystic nodal metastases, particularly when they occur in patients in whom clinical and radiographic evaluation does not find an obvious primary lesion, is that they may be mistaken as branchial cleft cysts or as carcinoma arising in a branchial cleft cyst.46, 47 The latter phenomenon is still reported today, but must be exceedingly rare.47 In this day and age, in a cystic squamous carcinoma in the neck surrounded by organized lymphoid tissue should be considered metastatic SCC until proven otherwise.

HPV-related cystic nodal metastases have also recently been shown to occasionally have true gland formation with mucin, to have columnar are lining cells, and to have, on rare occasions, apical cilia (Figure 6). In two recently published series,48, 49 determining these tumors as either ‘ciliated adenosquamous carcinoma’ or just ‘ciliated HPV-related carcinoma,’ 10 patients were reported in whom all had cystic neck lymph node metastases. Five of these patients had identifiable primary lesions in the oropharynx, most of these also showing ciliated cells and gland formation. All patients’ tumors were diffusely positive for p16 and were positive for high risk HPV DNA.

Branchial cleft cysts should have an overtly benign lining epithelium. These can express p16 by immunohistochemistry, but it is usually not strong and diffuse, typically being patchy, weaker, and more limited to the superficial cell layers.50, 51 Caution must be exercised on fine-needle aspiration specimens, however. Usually, the distinction is not difficult as the aspirations and any subsequent tissue resections show overtly benign squamous lining. However, any lesion with strong and diffuse p16 immunohistochemistry should probably be tested for high risk HPV to make sure that the lesion is not a bland appearing metastatic HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC.52 Branchial cleft cyst carcinoma can occur, at least theoretically, but very strict criteria must be applied, including at least the following (as proposed by Martin et al.53 and then later modified by Khafif et al.46): (1) location of the tumor in the anatomic region of the branchial cleft cyst or sinus as defined by Martin et al.53 (2) Histologic appearance of the tumor consistent with its origin from branchial vestiges; ie, SCC. (3) Presence of the carcinoma within the lining of an identifiable epithelial cyst. (4) Identification of transition from the normal squamous epithelium of the cyst to carcinoma. (5) Absence of any identifiable primary malignant tumor after exhaustive evaluation of the patient. Another modern criterion must almost certainly be lack of diffuse p16 reactivity and lack of high-risk HPV. As the most helpful criterion is supposed to be transition from benign appearing squamous epithelium into cancer, one still has to be careful with HPV-related carcinoma metastases because they can contain extremely bland-appearing areas of squamous lining.

Small Cell Carcinoma

Small cell (or high-grade neuroendocrine) carcinoma is well documented in the oropharynx, albeit in much smaller numbers than for laryngeal, sinonasal, and oral cavity ones54 Since small-cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix are frequently HPV-related, it stood to reason that the same might be true in the oropharynx. Until recently, however, this had not been clearly investigated. Recent studies have shown many oropharyngeal SCC to be transcriptionally active high-risk HPV positive.17, 18, 19 Morphologically, they are no different than the same tumors arising elsewhere, with the only exception being that the ‘combined’ tumors (ie, those mixed with a conventional carcinoma component) in the oropharynx are sometimes mixed with nonkeratinizing SCC.18

The differential diagnosis for oropharyngeal small carcinoma includes nonkeratinizing SCC, basaloid SCC, and adenoid cystic carcinoma. Also, rare cases of metastatic small-cell carcinoma from the lung to the oropharynx have been described. Small-cell carcinoma and nonkeratinizing SCC are blue cell tumors with high rates of apoptosis and mitosis, although small-cell carcinoma tends to have more necrosis. Small-cell carcinomas are more sheet-like and SCC more nested, but the real key is cytology. Small-cell carcinoma is composed of cells with extremely high N:C ratios, tear drop shaped nuclei with tapered projections, and stippled chromatin (Figure 7). However, this can be very subtle so it is recommended to have a low threshold for confirmatory immunochemistry. A recommended panel would include TTF-1, p40, synaptophysin, chromogranin, and possibly cytokeratin 5/6 (online). Basaloid SCC has a jigsaw puzzle pattern of growth with stromal hyaline material and round nuclei.21 Solid adenoid cystic carcinoma is also exquisitely nested, often with a jigsaw puzzle pattern, and almost always has at least small foci with rounded collections of basophilic basement-membrane material mimicking true duct formation.55 Nuclei are round to oval, not molding to each other, and without salt and pepper chromatin. Again, immunohistochemistry can be very useful in distinguishing these entities from small-cell carcinoma.56, 57

Conclusion

There are many unusual morphologic patterns seen in HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinomas. From the typical nonkeratinizing SCC to cystic nodal metastases, ciliated cells, and small cell carcinoma, these tumors are diverse and challenging to diagnose As such, it is not a stretch to compare HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinomas to the Frank Abagnale from real life, and from the play and movie ‘Catch Me If You Can’. He masquerades as all manner of people he is not. We as pathologists are tissue detectives so must, just like the detective Carl Hanratty from the story, find and call out HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinomas wherever and however we find them so that they can be managed and the destruction they can produce avoided.

References

Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R et al, Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:24–35.

Marur S, D'Souza G, Westra WH et al, HPV-associated head and neck cancer: a virus-related cancer epidemic. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:781–789.

Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF et al, Epidemiology of human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3235–3242.

McIlwain WR, Sood AJ, Nguyen SA et al, Initial symptoms in patients with HPV-positive and HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;140:441–447.

Benson E, Li R, Eisele D et al, The clinical impact of HPV tumor status upon head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Oncol 2014;50:565–574.

Hayes DN, Van Waes C, Seiwert TY . Genetic landscape of human papillomavirus-associated head and neck cancer and comparison to tobacco-related tumors. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3227–3234.

Yom SS, Gillison ML, Trotti AM . Dose de-escalation in human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal cancer: first tracks on powder. Intern J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2015;93:986–988.

Gondim DD, Haynes W, Wang X et al, Histologic typing in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: A 4-year prospective practice study with p16 and high-risk hpv mrna testing correlation. Am J Surg Pathol 2016;40:1117–1124.

El-Mofty SK . Human papillomavirus-related head and neck squamous cell carcinoma variants. Sem Diagn Pathol 2015;32:23–31.

Westra WH . The changing face of head and neck cancer in the 21st century: the impact of HPV on the epidemiology and pathology of oral cancer. Head Neck Pathol 2009;3:78–81.

Perry ME . The specialised structure of crypt epithelium in the human palatine tonsil and its functional significance. J Anat 1994;185:111–127.

Chernock RD, El-Mofty SK, Thorstad WL, et al. HPV-related nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: utility of microscopic features in predicting patient outcome. Head Neck Pathol 2009;3:186–194.

Lewis JS Jr, Khan RA, Masand RP et al, Recognition of nonkeratinizing morphology in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma - a prospective cohort and interobserver variability study. Histopathol 2012;60:427–436.

Chernock RD . Morphologic features of conventional squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: 'keratinizing' and 'nonkeratinizing' histologic types as the basis for a consistent classification system. Head Neck Pathol 2012;6 (Suppl 1):S41–S47.

Westra WH . The morphologic profile of HPV-related head and neck squamous carcinoma: implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and clinical management. Head Neck Pathol 2012;6 (Suppl 1):S48–S54.

Cai C, Chernock RD, Pittman ME et al, Keratinizing-type squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: p16 overexpression is associated with positive high-risk HPV status and improved survival. Am J Surg Pathol 2014;38:809–815.

Bates T, McQueen A, Iqbal MS et al, Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the oropharynx harbouring oncogenic HPV-infection. Head Neck Pathol 2014;8:127–131.

Bishop JA, Westra WH . Human papillomavirus-related small cell carcinoma of the oropharynx. Am J Surg Pathol 2011;35:1679–1684.

Kraft S, Faquin WC, Krane JF . HPV-associated neuroendocrine carcinoma of the oropharynx: a rare new entity with potentially aggressive clinical behavior. Am J Surg Pathol 2012;36:321–330.

Bishop JA, Lewis JS Jr., Rocco JW et al, HPV-related squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: An update on testing in routine pathology practice. Sem Diagn Pathol 2015;32:344–351.

Cardesa A, Zidar N, Ereno C et al Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma. In: Barnes EL, Eveson JW, Reichart P (eds). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours - Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2005, pp 125–126.

Begum S, Westra WH . Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck is a mixed variant that can be further resolved by HPV status. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:1044–1050.

Chernock RD, Lewis JS Jr., Zhang Q et al, Human papillomavirus-positive basaloid squamous cell carcinomas of the upper aerodigestive tract: a distinct clinicopathologic and molecular subtype of basaloid squamous cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol 2010;41:1016–1023.

Lewis JS Jr, Scantlebury JB, Luo J et al, Tumor cell anaplasia and multinucleation are predictors of disease recurrence in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, including among just the human papillomavirus-related cancers. Am J Surg Pathol 2012;36:1036–1046.

Ukpo OC, Flanagan JJ, Ma XJ et al, High-risk human papillomavirus E6/E7 mRNA detection by a novel in situ hybridization assay strongly correlates with p16 expression and patient outcomes in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2011;35:1343–1350.

Dahlstrom KR, Calzada G, Hanby JD et al, An evolution in demographics, treatment, and outcomes of oropharyngeal cancer at a major cancer center: a staging system in need of repair. Cancer 2013;119:81–89.

Hong AM, Martin A, Armstrong BK et al, Human papillomavirus modifies the prognostic significance of T stage and possibly N stage in tonsillar cancer. Ann Oncol 2013;24:215–219.

Lewis JS Jr., Chernock RD . Human papillomavirus and Epstein Barr virus in head and neck carcinomas: suggestions for the new WHO classification. Head Neck Pathol 2014;8:50–58.

Jo VY, Mills SE, Stoler MH et al, Papillary squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: frequent association with human papillomavirus infection and invasive carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:1720–1724.

Mehrad M, Carpenter DH, Chernock RD et al. Papillary squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: clinicopathologic and molecular features with special reference to human papillomavirus. Am J Surg Pathol 2013;37:1349–1356.

Bishop JA, Ma XJ, Wang H et al, Detection of transcriptionally active high-risk HPV in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma as visualized by a novel E6/E7 mRNA in situ hybridization method. Am J Surg Pathol 2012;36:1874–1882.

Carpenter DH, El-Mofty SK, Lewis JS Jr. . Undifferentiated carcinoma of the oropharynx: a human papillomavirus-associated tumor with a favorable prognosis. Mod Pathol 2011;24:1306–1312.

Cardesa A, Zidar N, Nadal A et al, Papillary squamous cell carcinoma, In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, (eds). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours - Pathology and Genetics Head and Neck Tumours. IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2005, p 126.

Singhi AD, Stelow EB, Mills SE et al, Lymphoepithelial-like carcinoma of the oropharynx: a morphologic variant of HPV-related head and neck carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:800–805.

Cardesa A, Zidar N, Alos L et al Adenosquamous carcinoma. In: Barnes L, Eveson J, Reichart P, (eds). Pathology and Genetics Head and Neck Tumours. IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2005, pp 130–131.

Masand RP, El-Mofty SK, Ma XJ et al, Adenosquamous carcinoma of the head and neck: relationship to human papillomavirus and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol 2011;5:108–116.

Bishop JA, Montgomery EA, Westra WH . Use of p40 and p63 immunohistochemistry and human papillomavirus testing as ancillary tools for the recognition of head and neck sarcomatoid carcinoma and its distinction from benign and malignant mesenchymal processes. Am J Surg Pathol 2014;38:257–264.

Watson RF, Chernock RD, Wang X et al, Spindle cell carcinomas of the head and neck rarely harbor transcriptionally-active human papillomavirus. Head Neck Pathol 2013;7:250–257.

Patel KR, Chernock RD, Zhang TR et al, Verrucous carcinomas of the head and neck, including those with associated squamous cell carcinoma, lack transcriptionally active high-risk human papillomavirus. Hum Pathol 2013;44:2385–2392.

Odar K, Kocjan BJ, Hosnjak L et al, Verrucous carcinoma of the head and neck - not a human papillomavirus-related tumour? J Cell Mol Med 2014;18:635–645.

Cantrell SC, Peck BW, Li G et al, Differences in imaging characteristics of HPV-positive and HPV-Negative oropharyngeal cancers: a blinded matched-pair analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013;34:2005–2009.

Chernock RD, Lewis JS . Approach to metastatic carcinoma of unknown primary in the head and neck: squamous cell carcinoma and beyond. Head Neck Pathol 2015;9:6–15.

Holmes BJ, Maleki Z, Westra WH . The fidelity of p16 staining as a surrogate marker of human papillomavirus status in fine-needle aspirates and core biopsies of neck node metastases: implications for HPV testing protocols. Acta Cytol 2015;59:97–103.

Holmes BJ, Westra WH . The expanding role of cytopathology in the diagnosis of HPV-related squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Diagn Cytopathol 2014;42:85–93.

Jalaly JB, Lewis JS Jr, Collins BT et al, Correlation of p16 immunohistochemistry in FNA biopsies with corresponding tissue specimens in HPV-related squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx. Cancer Cytopathol 2015;123:723–731.

Khafif RA, Prichep R, Minkowitz S . Primary branchiogenic carcinoma. Head Neck 1989;11:153–163.

Bradley PT, Bradley PJ . Branchial cleft cyst carcinoma: fact or fiction? Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;21:118–123.

Radkay-Gonzalez L, Faquin W, McHugh JB et al, Ciliated adenosquamous carcinoma: expanding the phenotypic diversity of human papillomavirus-associated tumors. Head Neck Pathol 2016;10:167–175.

Bishop JA, Westra WH . Ciliated HPV-related Carcinoma: A well-differentiated form of head and neck carcinoma that can be mistaken for a benign cyst. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:1591–1595.

Cao D, Begum S, Ali SZ et al, Expression of p16 in benign and malignant cystic squamous lesions of the neck. Hum Pathol 2010;41:535–539.

Pai RK, Erickson J, Pourmand N et al, p16(INK4A) immunohistochemical staining may be helpful in distinguishing branchial cleft cysts from cystic squamous cell carcinomas originating in the oropharynx. Cancer 2009;117:108–119.

Goldenberg D, Begum S, Westra WH et al, Cystic lymph node metastasis in patients with head and neck cancer: An HPV-associated phenomenon. Head Neck 2008;30:898–903.

Martin H, Morfit HM, Ehrlich H . The case for branchiogenic cancer (malignant branchioma). Ann Surg 1950;132:867–887.

Barker JL Jr, Glisson BS, Garden AS et al, Management of nonsinonasal neuroendocrine carcinomas of the head and neck. Cancer 2003;98:2322–2328.

Fordice J, Kershaw C, El-Naggar A et al, Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: predictors of morbidity and mortality. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;125:149–152.

Serrano MF, El-Mofty SK, Gnepp DR et al, Utility of high molecular weight cytokeratins, but not p63, in the differential diagnosis of neuroendocrine and basaloid carcinomas of the head and neck. Hum Pathol 2008;39:591–598.

Klijanienko J, el-Naggar A, Ponzio-Prion A et al, Basaloid squamous carcinoma of the head and neck. Immunohistochemical comparison with adenoid cystic carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1993;119:887–890.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lewis, J. Morphologic diversity in human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: Catch Me If You Can!. Mod Pathol 30 (Suppl 1), S44–S53 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.152

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2016.152

This article is cited by

-

Clinical, morphologic and molecular heterogeneity of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer

Oncogene (2023)

-

Etiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of human papilloma virus-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma

International Journal of Clinical Oncology (2023)

-

HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer: epidemiology, molecular biology and clinical management

Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology (2022)

-

Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the tongue base: the clinicopathology of seven cases and evaluation of HPV and EBV status

Diagnostic Pathology (2020)

-

Metastatic HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Versus Primary Pulmonary Squamous Cell Carcinoma: is p16 Immunostain Useful?

Head and Neck Pathology (2020)