Abstract

Type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis can be diagnosed by and is synonymous with its pathognomonic histopathologic appearance called lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis. Type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis, also called IgG4-related pancreatitis, is the pancreatic manifestation of IgG4-related disease. However, the role of IgG4 in the pathogenesis of IgG4-related disease is unclear. We describe patients with LPSP without serum or tissue IgG4 abnormalities. From the Mayo Clinic database of autoimmune pancreatitis patients, we identified three patients with histologically confirmed type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis (lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis) who had normal serum IgG4 and no increase in IgG4-positive plasma cells in tissue. We reviewed original clinical records and pathologic specimens, and describe the clinical and histologic features of these three patients. All patients (age/gender: 63/F, 70/M and 68/M) had normal serum IgG and IgG4 levels, and multiple sections of pancreatic histology did not show increased IgG4-positive plasma cells. Two patients were diagnosed retrospectively following pancreatic surgery, one relapsed in another organ and one has remained relapse free. Another patient was diagnosed by pancreatic core biopsy and has suffered multiple relapses that have been controlled by rituximab. These cases highlight the fact that although the currently agreed upon name for type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis is IgG4-related pancreatitis, serum and tissue IgG4 abnormalities are best considered characteristic, but not essential for the diagnosis of this enigmatic condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Many years before the identification of autoimmune pancreatitis as a clinical entity, its characteristic histopathology was described as ‘lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis’. Kawaguchi et al1 described the process as ‘an unusual lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing inflammatory disease involving the total pancreas, common bile duct, gall bladder, and, in one patient, lip.’ The original histopathological findings of lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, interstitial fibrosis (ie, storiform fibrosis), acinar atrophy, and obliterative phlebitis are now recognized as the characteristic features of type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis (often referred to simply as ‘autoimmune pancreatitis’).

Although it has long been felt that the etiology of chronic pancreatitis cannot be ascertained by reviewing pancreatic histology, autoimmune pancreatitis is an exception. A recent international pathology concordance study found that expert pathologists were able to distinguish autoimmune pancreatitis from alcoholic and obstructive forms of chronic pancreatitis on the basis of histopathology alone (without the aid of IgG4 immunohistochemistry) with a sensitivity and specificity of 91 and 98%, respectively.2 We and others believe that histology alone is sufficient to definitively diagnose type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis, regardless of the serum or tissue IgG4 status.3, 4 The recently established International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis recognizes lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis as being independently diagnostic of autoimmune pancreatitis.4

In 2001, Hamano, et al5 established the association between lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis (ie, type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis) and elevated serum IgG4 levels. This discovery undoubtedly led to a better understanding of the multi-organ syndrome and a more complete picture of the disease spectrum, treatment response, and natural history.5 It also led to the understanding that IgG4-positive plasma cells are present in other organs/sites affected by this disease.6 Based on these observations, Kamisawa et al7 proposed the concept that the disease process in autoimmune pancreatitis and in other organs affected in subjects with autoimmune pancreatitis was ‘related’ to IgG4. Hence, the disease was named as IgG4-related disease.8 Further, a recent consensus conference suggested that specific sites of involvement be named using the descriptor ‘IgG4-related:’ (eg, IgG4-related pancreatitis, IgG4-related sialadenitis, IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis, and so on).8, 9

Thus, type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis is considered as the pancreatic manifestation of IgG4-related disease. Characteristic features of IgG4- related disease are frequent elevation in serum IgG4, increased numbers of IgG4-positive plasma cells in tissue, a characteristic pattern of organ involvement, and response to steroid treatment.8 However, the relationship between IgG4 and the disease named after it remains unclear.

We reviewed our cohort of autoimmune pancreatitis patients who had histologic analysis and describe three patients with characteristic histopathologic features of what would now be called IgG4-related pancreatitis, none of whom had elevated serum IgG4 or increased tissue IgG4. We discuss some of the challenges with using serum and tissue IgG4 levels for diagnosis in this disease in which the pathogenetic role of this immunoglobulin (if any) is not yet understood.

Materials and methods

The Mayo Clinic autoimmune pancreatitis database is prospectively managed by one of the authors (STC), and has been previously described.10, 11 As of 1 November 2013, it contained 131 patients with type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreatic tissue was available for review from 66 patients in the form of either a core biopsy (n=34) or a resected portion of pancreas (n=32). Of those with normal serum IgG4 levels (27/66), three patients also lacked tissue infiltration of the pancreas with IgG4-positive plasma cells. Two blocks were stained for IgG4 in subjects with resected pancreas specimens (cases nos. 1 and 3), whereas only one block was stained for IgG4 for the subject with a core needle biopsy (case no. 2) owing to limited tissue for analysis. Tissue processing was performed at the Mayo Medical Laboratories in Rochester, Minnesota. The IgG4 antibody used for cases nos. 1 and 2 was from Zymed/Invitrogen (mouse monoclonal HP6025) at a dilution of 1/100, and was performed using the Dual EnVision detection kit from Dako. For case no. 3, the IgG4 antibody was acquired pre-dilute through Ventana using the mouse monoclonal MRQ-44. The area with the highest density of IgG4-positive plasma cells was selected. The maximal number of IgG4-positive cells was determined by scanning at low power ( × 40) for the areas with the greatest density of positive cells, then examining several high power fields ( × 400) in that area.

Results

Case No. 1

A 63-year-old woman presented in 1995 with painless jaundice (total bilirubin 7.8 mg/dl and alkaline phosphatase 702 U/l, AST 108 U/l, and ALT 202 U/l) and a 10-pound weight loss. A CT scan of the abdomen showed a mass in the head of the pancreas with obstruction of the common bile duct, and dilation of the intrahepatic bile duct and pancreatic duct. She also had an incidentally noted area of low attenuation in the left kidney. She underwent a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. At that time, the pathology was interpreted as ‘chronic pancreatitis with extensive tumefactive fibrosis.’ Multiple regional lymph nodes were negative for malignancy and the postoperative recovery was uncomplicated.

There were no interval medical events until 2008 when she underwent evaluation for atypical abdominal pain. A CT scan showed a normal-appearing liver with mildly prominent bilateral intrahepatic ducts. The pancreas was atrophic with a sub-centimeter pancreatic cyst. The left kidney was atrophic with scarring in the upper pole. A subsequent MRI/MRCP did not demonstrate biliary narrowing or dilation. During this visit, the possibility of autoimmune pancreatitis was considered. Serum IgG4 level was normal at 80.8 mg/dl (normal 8.0–140.0), as was the total IgG level of 1040 mg/dl (normal 600–1500). Her surgical resection specimen was reexamined, and it showed periductal lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, storiform fibrosis, and obliterative phlebitis (Figure 1). There were no neutrophils in the inflamed lobules or in pancreatic duct epithelium (ie, no granulocytic epithelial lesions). Immunohistochemical stain for IgG4 was negative (only one IgG4-positive cell/high power field), but a diagnosis of type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis was made based on the characteristic histology (lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis). In the absence of active disease attributable to IgG4-related disease, she was not started on medical treatment. She has been followed for over 17 years from the date of her original surgery, with no evidence of recurrent pancreatic or biliary disease.

Histologic features of lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis/type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis from the resected pancreas of subject no. 1. (a) Periductal lymphoplasmacytic infiltration without IgG4-positive cell staining (b). Storiform fibrosis is shown (c) without IgG4-positive cell staining (d). Perineural inflammation (e) without IgG4-positive cell staining (f). Obliterative phlebitis is shown at both low (g, asterisk) and high power (h).

Case No. 2

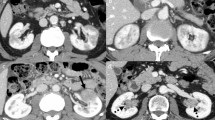

A 70-year-old man developed painless jaundice in 2009 (total bilirubin 11.0 mg/dl, alkaline phosphatase 285 U/l, AST 128 U/l, and ALT 325 U/l). An abdominal CT scan at that time showed a prominent pancreatic head, but no definite mass or pancreatic duct dilation. There were multiple wedge-shaped low-density renal lesions. An ERCP showed a distal biliary stricture and pancreatic duct narrowing without upstream dilation. A plastic biliary stent was placed. Serum IgG4 level was 40.1 mg/dl (normal 2.4–121.0) and total IgG level was 1020 mg/dl (normal 767–1590). EUS of the pancreas showed hypoechoic changes in the body and tail. The wall of the common bile duct was diffusely thickened to 2–3 mm, with maximal thickness (7 mm) located in the intrapancreatic portion. Trucut biopsies of the pancreas were obtained and demonstrated lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, storiform fibrosis, obliterative phlebitis, and scant IgG4 staining (maximum density of five IgG4-positive cells/high power field; Figure 2); confirming a diagnosis of type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis.

Findings of lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis/type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis without tissue IgG4 infiltration (never >1 IgG4-positive cell/hpf) in the Trucut biopsy of subject no. 2. (a and b) Lymphoplasmacytic inflammation with storiform fibrosis (which is attenuated due to crush artifact). (c) Obliterative phlebitis (asterisk; artery on the left). (d) Negative IgG4 immunostaining.

He was started on prednisone, and follow-up imaging 1 month later showed resolution of the pancreatic head fullness, atrophy of the remaining pancreas, normalization of liver test abnormalities, and a decrease in the size of his renal lesions. Complete resolution of the distal stricture was demonstrated 2 months later and the stent was removed. He had two subsequent biliary relapses (serum IgG4 remained normal) involving the proximal extrahepatic biliary tree, one occurring during treatment with azathioprine. Owing to the refractory nature of his disease, he is currently being treated with rituximab.

Case No. 3

A 68-year-old man presented in 2012 with painless jaundice (total bilirubin 12.3 mg/dl, alkaline phosphatase 320 U/l, AST 226 U/l, and ALT 561 U/l). A CA 19-9 level was elevated at 557 U/l (normal <55 U/l), but serum IgG4 was not evaluated. An abdominal CT scan showed vague fullness in the head of the pancreas, without a definite mass, and extrahepatic biliary duct dilation. Endoscopic ultrasonography of the pancreas showed hyperechoic foci and stranding in the head, but no definite mass, so FNA was not performed. The bile duct wall was 1–2 mm in thickness. ERCP revealed a 2-cm pancreatic duct stricture in the head without upstream dilation. Intraductal ultrasound showed a 2-cm pancreatic mass centered on the pancreatic duct of variable echogenicity and with a well-defined border. Brushings from the biliary and pancreatic ducts for cytology and FISH studies for biliary tract malignancy were both negative. As a result of the high suspicion for a pancreatic neoplasm, he underwent a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. The resected specimen was interpreted as ‘severe chronic pancreatitis’ and grossly had a firm area in the region of the pancreatic head, but without a definite mass.

He was seen 12 months later for clinical follow-up and was having postprandial symptoms of abdominal bloating, fullness, and intermittent loose stools. Laboratory evaluation was notable for vitamin D and E deficiencies. A CT scan of the abdomen showed a normal-appearing pancreas remnant, and periaortic soft tissue thickening, that was not present previously. The new finding raised the question of IgG4-related disease as an underlying diagnosis. His surgical resection was reexamined and showed periductal lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, storiform fibrosis, and obliterative phlebitis (Figures 3 and 4). Immunohistochemical stain for IgG4 showed only rare IgG4-positive cells. Although a serum IgG4 level was low (<0.3 mg/dl, normal 2.4–121.0) the total IgG level was normal (917 mg/dl, normal range 767–1,590). The serum IgG4 level was unchanged when evaluated with serial dilutions. The combination of definitive histology for type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis and characteristic other organ involvement of the retroperitoneum confirmed the diagnosis of IgG4-related disease. As a consequence of the periaortic thickening, suggesting active inflammation, steroid therapy was initiated. Follow-up imaging 1 month later showed radiographic improvement. He was started on pancreatic enzyme therapy due to steatorrhea (confirmed on a quantitative fecal fat collection) and fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies.

Typical findings of lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis including lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, storiform fibrosis, and obliterative phlebitis seen at medium power in a resected pancreatic specimen from subject no. 3. Black boxes denote areas seen at higher magnification in Figure 4.

Discussion

The three patients described here had all features of IgG4-related disease except IgG4 abnormalities: they each met histopathologic criteria for lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis, and they had other organ involvement and responded to steroids, when used. While representing only a small subset of our cohort, these cases highlight the limitations of IgG4 abnormalities as diagnostic tools, and raise the question of what the relationship is between IgG4-related disease and IgG4.

In this series, all subjects had characteristic histology, with lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, storiform fibrosis, and obliterative phlebitis. In addition, each had imaging evidence of other organ involvement, including the biliary tree, kidneys, and retroperitoneal fibrosis. Although the clinical outcomes were different for these subjects, they represent somewhat characteristic courses: the first and third subjects presented with obstructive jaundice and abnormal imaging of the pancreatic head suspicious for neoplasm, thus, resections were performed. The lack of recurrent disease in the first subject following resection is not surprising, as only 20% of patients have a relapse following pancreaticoduodenectomy.11 However, subsequent development of extrapancreatic organ involvement in the third subject is a recognized scenario that may result in a retrospective autoimmune pancreatitis diagnosis following surgery. The second patient had a typical response to steroid therapy for autoimmune pancreatitis, but later developed steroid-responsive sclerosing cholangitis with multiple relapses. Recurrence, with loss of response to azathioprine is not uncommon. We have reserved rituximab for these immunomodulator-resistant patients with reasonable success.10

A review of the literature shows that IgG4 abnormalities in tissue and serum are neither sufficient nor diagnostic of IgG4-related disease. An initial report of tissue infiltration with IgG4-positive plasma cells suggested that this finding was specific for autoimmune pancreatitis, at least in comparison with alcoholic pancreatitis and Sjögren’s syndrome.12 That expectation has not held up over time. It has been noted that low levels (5–10 per high power field) of IgG4-positive plasma cells are not specific for autoimmune pancreatitis, and may occur in chronic alcoholic pancreatitis (44%) and pancreatic cancer (24%).13 The specificity issue has been further investigated in multiple studies involving multiple organs, and abundant tissue IgG4 has been reported in numerous other conditions including pancreatobiliary malignancies such as pancreatic cancer and cholangiocarcinoma (Table 1). The recent consensus statement on the pathology of IgG4-related disease addressed this issue in two ways: (i) by requiring at least two of three histologic criteria (lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, storiform fibrosis, and obliterative phlebitis), except in organs known to not feature fibrosis (such as lacrimal glands and lymph nodes), and (ii) by establishing high cutoff values for tissue IgG4-positive plasma cell numbers (50 per high power field in a resected pancreas, 100 per high power field in a resected salivary gland, and so on).14 Although it is definitely worth remembering that increased tissue IgG4 is not diagnostic of IgG4-related disease, we should also recognize an important corollary, ie, tissue IgG4 infiltration is not always present in IgG4-related disease. Also, although we have presented a group of patients with truly IgG4-negative disease, there may also be a group of patients with minor amounts of nonspecific IgG4 tissue infiltration.

It is well recognized now that elevated serum IgG4 is not specific for autoimmune pancreatitis (or any other manifestation of IgG4-related disease). Elevated serum IgG4 levels have been reported in ∼10% of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) up to 14% of those with cholangiocarcinoma and up to 10% of patients with pancreatic cancer (Table 2). These ‘false positive’ elevations are of considerable diagnostic concern, because each of these serious pancreatobiliary diseases shares clinical features with the pancreatobiliary manifestations of IgG4-related disease. As shown by Ghazale et al15, the specificity of serum IgG4 can be increased by using a cutoff of >2 times the upper limit of normal, but this improvement in specificity substantially limits the sensitivity. The combination of false positive test results and the low disease prevalence leads to a very low positive predictive value for elevated serum IgG4 levels for the diagnosis of IgG4- related disease (<10%; Ngwa et al38).

Even at the currently accepted upper limit of normal, the high sensitivity (95%) of elevated serum IgG4 for detecting autoimmune pancreatitis initially reported by Hamano et al5 has not been replicated by subsequent larger studies. In fact, clinical series have reported the prevalence of elevated serum IgG4 levels for autoimmune pancreatitis to be as low as 43% (Table 3). In a recent international multicenter study, the rate of IgG4 seropositivity was ∼65% in 160 patients with histologically confirmed type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis, which appears to be a fair estimate.16 One contributing factor to the poor sensitivity of serum IgG4 is some patients with markedly elevated levels will have a falsely negative level owing to the prozone (or hook) effect.17 The serum of case no. 3 was evaluated with a dilution assay to ensure that the serum IgG4 was truly negative. However, cases nos. 1 and 2 were evaluated before the IgG4 prozone effect was appreciated, so the possibility of a false negative is present. Nonetheless, we believe that the normal serum total IgG levels and absence of IgG4 tissue infiltration support our impression of IgG4 negativity in these subjects.

While the argument that type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis can occur in patients without tissue IgG4 makes the story of IgG4-related disease more complicated, we feel that it more accurately defines the bounds of the disease spectrum. To date, the role of IgG4 antibodies in IgG4-related disease remains unknown, and overemphasizing this marker as a diagnostic requirement may overlook a subset of treatable patients. We are not advocating for loosening the diagnostic criteria, but rather want to draw attention to a limitation of the current classification system. By themselves, neither clinical phenotype nor serum IgG4 positivity can reliably diagnose patients. In contrast, the histologic findings are specific and sufficient to independently diagnose autoimmune pancreatitis.13 We recognize that there are differences in opinions regarding the safety and optimal means of obtaining histologic specimens, but, those concerns aside, we propose that the histology should be considered as the gold standard against which other ‘definitive’ means of diagnosis should be compared.

Although histopathologic pattern is diagnostic in most organs, not all sites demonstrate the complete spectrum of histologic changes. The lack of characteristic histopathology is most pronounced in lymph nodes, lymphoma-like presentations in the orbit, and certain kidney manifestations, such as tubulointerstitial nephritis. In these cases, tissue IgG4 may have a more critical role in the diagnosis, as will the presence of multifocal disease with characteristic morphology in other organs.

In summary, many questions remain regarding the disease entity currently referred to as IgG4-related disease. The pathogenesis remains poorly understood, but it appears that IgG4 antibodies are not directly pathogenic. Serum and tissue IgG4 status have inadequate sensitivity and specificity for reliably distinguishing IgG4-related disease from other important diagnostic considerations, including PSC, cholangiocarcinoma, and pancreatic cancer. In contrast, histology is often diagnostic in IgG4-related disease independent of IgG4 status. We are hopeful that advances in our understanding of the pathogenesis of IgG4-related disease will clarify the issues we have raised and permit further refinement of the disease nomenclature.

References

Kawaguchi K, Koike M, Tsuruta K et al. Lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis with cholangitis: a variant of primary sclerosing cholangitis extensively involving pancreas. Hum Pathol 1991;22:387–395.

Chari ST, Kloeppel G, Zhang L et al. Histopathologic and clinical subtypes of autoimmune pancreatitis: the Honolulu consensus document. Pancreas 2010;39:549–554.

Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Levy MJ et al. Diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis: the Mayo Clinic experience. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4:1010–1016 quiz 934.

Shimosegawa T, Chari ST, Frulloni L et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis: guidelines of the International Association of Pancreatology. Pancreas 2011;40:352–358.

Hamano H, Kawa S, Horiuchi A et al. High serum IgG4 concentrations in patients with sclerosing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med 2001;344:732–738.

Kamisawa T, Funata N, Hayashi Y et al. A new clinicopathological entity of IgG4-related autoimmune disease. J Gastroenterol 2003;38:982–984.

Kamisawa T, Nakajima H, Egawa N et al. IgG4-related sclerosing disease incorporating sclerosing pancreatitis, cholangitis, sialadenitis and retroperitoneal fibrosis with lymphadenopathy. Pancreatology 2006;6:132–137.

Umehara H, Okazaki K, Masaki Y et al. A novel clinical entity, IgG4-related disease (IgG4RD): general concept and details. Mod Rheumatol 2012;22:1–14.

Stone JH, Khosroshahi A, Deshpande V et al. Recommendations for the nomenclature of IgG4-related disease and its individual organ system manifestations. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:3061–3067.

Hart PA, Topazian MD, Witzig TE et al. Treatment of relapsing autoimmune pancreatitis with immunomodulators and rituximab: the Mayo Clinic experience. Gut 2013;62:1607–1615.

Sah RP, Chari ST, Pannala R et al. Differences in clinical profile and relapse rate of type 1 versus type 2 autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2010;139:140–148 quiz e12-3.

Kamisawa T, Funata N, Hayashi Y et al. Close relationship between autoimmune pancreatitis and multifocal fibrosclerosis. Gut 2003;52:683–687.

Zhang L, Notohara K, Levy MJ et al. IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration in the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis. Mod Pathol 2007;20:23–28.

Deshpande V, Zen Y, Chan JK et al. Consensus statement on the pathology of IgG4-related disease. Mod Pathol 2012;25:1181–1192.

Ghazale A, Chari ST, Smyrk TC et al. Value of serum IgG4 in the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis and in distinguishing it from pancreatic cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:1646–1653.

Kamisawa T, Chari ST, Giday SA et al. Clinical profile of autoimmune pancreatitis and its histological subtypes: an international multicenter survey. Pancreas 2011;40:809–814.

Khosroshahi A, Cheryk LA, Carruthers MN et al. Brief Report: spuriously low serum IgG4 concentrations caused by the prozone phenomenon in patients with IgG4-related disease. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:213–217.

Deshpande V, Chicano S, Finkelberg D et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis: a systemic immune complex mediated disease. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:1537–1545.

Dhall D, Suriawinata AA, Tang LH et al. Use of immunohistochemistry for IgG4 in the distinction of autoimmune pancreatitis from peritumoral pancreatitis. Hum Pathol 2010;41:643–652.

Deshpande V, Sainani NI, Chung RT et al. IgG4-associated cholangitis: a comparative histological and immunophenotypic study with primary sclerosing cholangitis on liver biopsy material. Mod Pathol 2009;22:1287–1295.

Boonstra K, Culver EL, de Buy Wenniger LM et al. Serum IgG4 and IgG1 for distinguishing IgG4-associated cholangitis from primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology 2013;59:1954–1963.

Zhang L, Lewis JT, Abraham SC et al. IgG4+ plasma cell infiltrates in liver explants with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:88–94.

Zen Y, Quaglia A, Portmann B . Immunoglobulin G4-positive plasma cell infiltration in explanted livers for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Histopathology 2011;58:414–422.

Oseini AM, Chaiteerakij R, Shire AM et al. Utility of serum immunoglobulin G4 in distinguishing immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis from cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology 2011;54:940–948.

Harada K, Shimoda S, Kimura Y et al. Significance of IgG4-positive cells in extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Molecular mechanism of IgG4 reaction in cancer tissue. Hepatology 2012;56:157–164.

Navaneethan U, Bennett AE, Venkatesh PG et al. Tissue infiltration of IgG4+ plasma cells in symptomatic patients with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. J Crohns Colitis 2011;5:570–576.

Sweetser S, Ahlquist DA, Osborn NK et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: support for autoimmunity. Dig Dis Sci 2012;57:496–502.

Mendes FD, Jorgensen R, Keach J et al. Elevated serum IgG4 concentration in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:2070–2075.

Hirano K, Kawabe T, Yamamoto N et al. Serum IgG4 concentrations in pancreatic and biliary diseases. Clin Chim Acta 2006;367:181–184.

Bjornsson E, Chari S, Silveira M et al. Primary sclerosing cholangitis associated with elevated immunoglobulin G4: clinical characteristics and response to therapy. Am J Ther 2011;18:198–205.

Choi EK, Kim MH, Lee TY et al. The sensitivity and specificity of serum immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin G4 levels in the diagnosis of autoimmune chronic pancreatitis: Korean experience. Pancreas 2007;35:156–161.

Raina A, Krasinskas AM, Greer JB et al. Serum immunoglobulin G fraction 4 levels in pancreatic cancer: elevations not associated with autoimmune pancreatitis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2008;132:48–53.

Ryu JK, Chung JB, Park SW et al. Review of 67 patients with autoimmune pancreatitis in Korea: a multicenter nationwide study. Pancreas 2008;37:377–385.

Raina A, Yadav D, Krasinskas AM et al. Evaluation and management of autoimmune pancreatitis: experience at a large US center. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:2295–2306.

Frulloni L, Scattolini C, Falconi M et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis: differences between the focal and diffuse forms in 87 patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:2288–2294.

Song TJ, Kim MH, Moon SH et al. The combined measurement of total serum IgG and IgG4 may increase diagnostic sensitivity for autoimmune pancreatitis without sacrificing specificity, compared with IgG4 alone. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:1655–1660.

Maire F, Le Baleur Y, Rebours V et al. Outcome of patients with type 1 or 2 autoimmune pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:151–156.

Ngwa TN, Law R, Murray D et al. Serum immunoglobulin g4 level is a poor predictor of immunoglobulin g4-related disease. Pancreas 2014;43:704–707.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hart, P., Smyrk, T. & Chari, S. Lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis without IgG4 tissue infiltration or serum IgG4 elevation: IgG4-related disease without IgG4. Mod Pathol 28, 238–247 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2014.91

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2014.91

This article is cited by

-

Serum and histological IgG4-negative type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis

Clinical Journal of Gastroenterology (2019)

-

Diagnosis and Management of Autoimmune Pancreatitis

Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology (2017)

-

Adult bile duct strictures: differentiating benign biliary stenosis from cholangiocarcinoma

Medical Molecular Morphology (2016)