Abstract

Interpretation of gastrointestinal tract mesenchymal lesions is simplified merely by knowing in which anatomic layer they are usually found. For example, Kaposi sarcoma is detected on mucosal biopsies, whereas inflammatory fibroid polyp is nearly always in the submucosa. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are generally centered in the muscularis propria. Schwannomas are essentially always in the muscularis propria. Mesenteric lesions are usually found in the small bowel mesentery. Knowledge of the favored layer is even most important in interpreting colon biopsies, as many mesenschymal polyps are encountered in the colon. Although GISTs are among the most common mesenchymal lesions, we will concentrate our discussion on other mesenchymal lesions, some of which are in the differential diagnosis of GIST, and point out some diagnostic pitfalls, particularly in immunolabeling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Case report

A 4-cm lesion was resected from the gastric antrum of a 56-year-old woman. The surgeon requested KIT mutational analysis. A frozen section was requested. An interpretation of glomus tumor was made on frozen section. Images of the tumor are shown in Figures 1, 2, 3, 4.

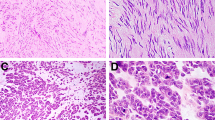

Glomus tumor. (a) These generally arise in the muscularis propria of the stomach. The cells are perfectly round. There is hemangiopericytoma-like vascular pattern. (b) Note the round nuclei and the well-developed cell borders. (c) Smooth muscle actin immunolabeling. Glomus cells are modified smooth muscle cells. They express actin and calponin but not desmin. (d) Collagen type 4 immunolabeling. Each cell is invested in a network of collagen type 4.

Malignant-appearing gastrointestinal glomus tumor. (a) This lesion arose in the muscularis propria of the small bowel. It has areas similar to those depicted in Figure 1 but with transitions to solid and spindle zones. (b) Note the spindling and mitotic activity. (c) Calponin stain. (d) Collagen type 4 stain.

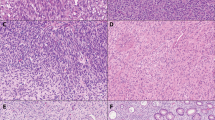

Gastric Kaposi sarcoma. (a) This example is classic and features spindle cells, hemosiderin deposition, and hyaline globule formation. (b) This more subtle example merges with the existing lamina propria but appears more spindled and sclerotic. Such examples are easily mistaken for fibrosis. (c) HHV8 immunolabeling. (d) CD117 immunolabeling. This expression has no correlation with KIT mutations but can lead to a diagnostic pitfall.

Ganglioneuroma. (a) There is a proliferation of Schwann cells and peculiar appearing ganglion cells in colonic lamina propria. (b) Benign fibroblastic polyp of the colon/perineurioma. This example is associated with a serrated polyp, a characteristic association. (c) Schwann cell hamartoma. These lamina propria lesions are brightly eosinophilic and have a suggestion of palisading. They are incidental sporadic (as opposed to syndromic) lesions detected at screening colonoscopy.

Glomus tumors

As illustrated by the case above, gastrointestinal tract (GIT) glomus tumors almost always arise in the gastric muscularis propria but are occasionally found elsewhere in the GIT. They are rare in the GI tract and arise more commonly in the skin. The largest series of GIT glomus tumors (from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP)1) showed a female predominance and a median age at presentation of 55 years. A smaller Korean series limited to gastric glomus tumors showed a male predominance. Most tumors arose in the gastric antrum, and there were no metastases or recurrences (n=10, median follow up: 44.5 months).2 The vast majority are found in the stomach, where they not infrequently present with severe bleeding producing melena. Ulcer-like pain can also be a feature. About 20% of cases in the AFIP series were detected at the time of operations for other lesions. Tumors are circumscribed mural masses with a median diameter of 2.5 cm. They can bulge into the mucosa or externally toward the serosa. They are occasionally calcified on cut surface. Imaging studies may be diagnostically helpful; on endoscopic ultrasound, the tumor has distinct borders and shows a characteristic peripheral halo sign.3 On dynamic contrast-enhanced computer tomography, these tumors may show hemangioma-like globular enhancement. In one study, this pattern was exclusively observed in gastric or duodenal glomus tumors and was absent in other subepithelial lesions such as gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), schwannoma, ectopic pancreas, and leiomyoma.4 Glomus tumors are multinodular at scanning magnification, the nodules separated by strands of residual muscularis propria with ulceration of the overlying mucosa (Figures 1a and b). Tumor nodules are generally composed of solid sheets of cells that surround gaping capillary vessels showing a hemangiopericytoma-like pattern. Tumor cells also tend to be present in the muscular walls of larger vessels. The individual tumor cells are round with sharply defined cell membranes, perfectly rounded nuclei, and delicate chromatin. Some tumors have brightly eosinophilic cytoplasm.

As glomus tumors are composed of modified smooth muscle cells, they express smooth muscle actin (SMA), calponin, and h-caldesmon, but they lack desmin expression (Figure 1c). Pericellular net–like positivity is seen with basement membrane proteins (laminin and collagen type IV) (Figure 1d). Some cases have focal CD34 expression. Glomus tumors are negative for CD117/c-kit. Occasional cases are immunoreactive with synaptophysin, but these tumors lack chromogranin and keratin. Glomus tumors lack C-KIT mutations but some cases harbor MIR143-NOTCH fusions.5

Although most glomus tumors behave in a benign fashion, rare examples metastasize and are lethal (Figure 2).

Gastrointestinal mesenchymal lesions—mucosa to serosa

As a general approach to GIT mesenchymal tumors, it is easiest to know which types of lesions are encountered in which layer. Noting whether a tumor is centered in the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, or serosa goes a long way toward establishing a differential diagnosis; each type of lesion is often restricted to one of these layers. Table 1 shows the likely locations of various GIT mesenchymal lesions. In the following discussion, we mention several commonly encountered lesions of each layer, incorporating a few diagnostic pitfalls.

Mucosal lesions

Kaposi Sarcoma

In the present era of better control of HIV disease, we seldom encounter Kaposi sarcoma (KS) in our GIT material. However, when GIT involvement is encountered it is most likely to be detected in the mucosa rather than other layers of the GIT wall.6 When identified, there is often a history of extreme immunosuppression. Gastric KS can be extremely subtle on biopsies (Figures 3a and b) as the gastric lamina propria of the stomach often contains plasma cells, a feature of the backdrop of KS. If the spindle cell proliferation is noted, it typically appears more spindled than normal lamina propria and often contains hemosiderin, hyaline globules, and prominent plasma cells. The proliferation is composed of CD34-reactive spindle cells. Antibodies to HHV8 are also available to confirm this impression.

Moriz Kaposi's series established this tumor as a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Kaposi’s paper, entitled ‘Idiopathic multiple pigmented sarcoma of the skin’ described in detail five adult male patients, aged 40–68 years, and briefly mentions a boy aged 8–10 years.7 He believed the condition to be a generalized disease that proved rapidly fatal. Interest in the condition remained relatively dormant in the literature for the next 100 years until the disease began manifesting in immunosuppressed individuals, first in the setting of iatrogenic immunosuppression associated with solid organ transplantation and later as a feature of AIDS.

In the ‘classic’ or European form of the disease, KS typically affects male patients between the ages of 50 and 80 years. The peak incidence is in the sixth or seventh decade. Combining data from two large series8, 9 gives a male-to-female ratio of 11:1. A racial predilection is evident, with an increased incidence in men of Mediterranean descent or of Ashkenazic Jewish extraction.10 Isolated familial cases have been reported.11 The disease frequently follows an indolent course.8 Patients typically survive an average of 10–15 years following their initial diagnosis and commonly die of an unrelated cause. Secondary malignancies have been reported in >35% of the patients,12 with approximately half of these tumors being of hematopoietic/lymphoreticular derivation (ie, leukemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma). Cutaneous lesions are usually first noted in the distal portion of the lower extremities and evolve in stages, consisting initially of purple patches, followed by plaques and nodules. Over time, the lesions extend proximally, gradually coalesce, and may ulcerate. Some foci may regress, whereas others progress. Upper extremity and internal involvement may develop although the latter is often clinically silent.10

The African or ‘endemic’ form of KS was classically described in the northeast Zaire-northwest Ugandan region.10 In the early 1980s, this disease reportedly accounted for 9% of maligancies in Ugandan males and approximately 10% of all cancers in Zaire. The relationship to the HIV epidemic has somewhat clouded the issue of endemic disease, but there remains a subset of patients who are uninfected with HIV who seem to have an endemic form of KS;13, 14, 15 this presumably relates to HHV8 serotypes in various endemic areas.13, 14, 15

A third epidemiological subgroup at risk for KS is composed of individuals (primarily transplant patients) receiving potent, high-dose or long-term immunosuppressive therapy. The overall risk to these patients is relatively low. Kaposi's sarcoma is estimated to account about 5% of all malignancies in the transplant population.16 The mean interval to onset after transplantion is 16.5 months.17 Many of these individuals are also of Jewish or Mediterranean descent. However, females comprise a higher percentage of those affected; the male-to-female ratio ranges from 2 to 3:1. Although Kaposi’s sarcoma may assume a chronic or aggressive course in these patients, regression frequently follows discontinuation of the immunosuppressive treatment. Patients receiving immunosuppressive agents for various other collagen vascular and skin disorders are also included in this category.

The ‘epidemic’ or AIDS-related form of Kaposi’s sarcoma occurs in HIV-positive individuals. The risk of developing KS for untreated AIDS patients is estimated to be 300 times greater than that of other immunosuppressed individuals and 20 000 times greater that of the general population.18 In this group, KS frequently assumes an aggressive course. Areas prone to KS in the adult AIDS population include: the oral cavity, especially the hard palate, the tip of the nose, behind the ears, the trunk, penis, legs, and feet. Lesions more often involve the upper half of the body than in classic KS. Postmortem studies have demonstrated a high incidence of concurrent disease in lymph nodes, the GIT, and lungs. Pediatric cases of AIDS-KS have a proclivity for lymphadenopathic disease.

For years, the epidemiological features of KS, including the observation of disease in defined patient populations and the geographic distribution, were suggestive of an infectious etiology. Many organisms were considered over time, but novel viral DNA sequences were discovered in 1994 in KS lesions that were absent in normal tissue from the same individual.19 This virus, a member of the herpesvirus family, was named KS-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) and later classified as human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8).20

In subequatorial Africa, over 30% of the general population carries HHV-8 antibodies. Seropositivity for the virus ranges from 10 to 25% in the Mediterranean area. Where KS is not endemic, the seroprevalence of HHV-8 is around 2–5%.20

Evidence exists for saliva as a route of transmission. Transmission to children within families in endemic regions such as the Mediterranean and subequatorial Africa is not likely to be sexual, further supporting a salivary and close contact mode of transmission. The role of a sexual route of transmission in the male homosexual population remains under debate.20

When KS is seen in the GIT, the spindled component is often prominent, but it can be subtle in the stomach (Figures 3a and b). These cells form slit-like spaces that frequently contain red blood cells. Plasma cells and hemosiderin deposits are also usually apparent. Eosinophilic hyaline globules, 1–7 microns in size, are commonly present and form grape-like agglomerations, which are predominantly intracellular. These structures are thought to represent digested erythrocytes as the neoplastic cells seem to have phagocytic activity.21

Based on immunolabeling studies, KS is best regarded as a lesion of lymphatic endothelial cells, as it expresses CD34, CD31, Fli-1, VEGFR-3, and podoplanin (D2–40).22, 23, 24, 25 Virtually all examples show nuclear labeling with HHV-8 antibodies (Figure 3c).26 An important pitfall for the pathologist is to beware that KS often immunolabels with CD117 antibodies (Figure 3d).

Ganglioneuromas

Ganglioneuromas occur in two general settings:27 (a) as solitary isolated lesions and (b) syndromically as multiple lesions that either produce multiple exophytic polyps (‘ganglioneuromatous polyposis’) or poorly demarcated transmural proliferations (‘ganglioneuromatosis’).28 In solitary examples, there is no gender predominance, and lesions have been detected in adults from ages 20 to 90 years, with a peak incidence between the ages of 40 and 60 years (mean age about 50 years). The majority is found in the colon, generally the left side. Most patients are asymptomatic, and the lesions are detected during routine colonoscopy. Solitary lesions are not associated with genetic syndromes. In contrast, ganglioneuromatous polyposis is associated with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), and diffuse ganglioneuromatosis is associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type IIB and with NF1. Diffuse ganglioneuromatosis is found in virtually all patients with MEN IIB and often antedates the development of the endocrine neoplasms. Patients with MEN IIB and ganglioneuromatosis present with diverse GI symptoms, which may include constipation, diarrhea, difficulty in feeding, projectile vomiting, and crampy abdominal pain. Most syndromic GI tract ganglioneuromas are found in the colorectum and in patients younger (mean age of about 35 years) than those who have sporadic isolated ganglioneuromas.

Polypoid isolated ganglioneuromas are small sessile or pedunculated polyps that grossly resemble juvenile polyps or adenomas and are 1–2 cm. The polyps in ganglioneuromatous polyposis are multiple (20–40) and display greater variability than sporadic ones, ranging from 1 mm to >2 cm. Some are filiform. Rare pediatric examples of ganglioneuromatous polyposis have been reported in association with production of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide producing the watery diarrhea, hypokalemia, and achlorhydria syndrome.29, 30 Diffuse ganglioneuromatosis results in a poorly demarcated, whitish thickening that may be transmural.

At low magnification, polypoid sporadic ganglioneuromas often resemble juvenile or inflammatory polyps, in that they have disturbed crypt architecture and expanded lamina propria. At higher magnification, the lamina propria is expanded by collections of spindle cells within a fibrillary matrix and irregular nests and groups of ganglion cells (Figure 4a). Sporadic examples may also have submucosal extension and a plexiform arrangement involving the submucosal nerve plexus, such that they superficially resemble neurofibromas (differing by the presence of many ganglion cells). The ganglioneuromas in ganglioneuromatous polyposis show overlapping features with sporadic ganglioneuromas but tend to be more variable and have more numerous ganglion cells and filiform architecture. In diffuse ganglioneuromatosis, the process is centered in the myenteric plexus, is either diffusely intramural or transmural, and consists of fusiform expansions or confluent transmural ganglioneuromatous proliferations.

These lesions are easily diagnosed without immunohistochemistry, but the spindle cells react with S100 protein and the ganglion cells mark with neuron specific enolase (NSE), synaptophysin, and neurofilament protein (NFP).

The primary distinction is from neurofibroma, which is based on the presence of ganglion cells in ganglioneuromas and their lack in neurofibromas. When ganglion cells are sparse, NSE or synaptophysin staining may help detect them. Ganglioneuromas are distinguished from gangliocytic paraganglioma (PGL)by the presence of epithelioid cells in gangliocytic PGL; these latter cells may be keratin positive. Additionally, gangliocytic PGLs arise primarily in the duodenum, rather than the colon.

Sporadic ganglioneuromas are treated by polypectomy and seldom recur. Patients with syndromic ganglioneuromas must be carefully followed, based on their specific syndromes. Those with NF1 may develop other neural lesions, including malignant peripheral sheath tumors; those with MEN IIB may develop endocrine neoplasms. Ganglioneuromatous polyposis may herald Cowden disease, tuberous sclerosis, FAP, and juvenile polyposis, whereas the diffuse type is most likely associated with NF1 and MEN IIB. This latter type may cause strictures requiring resections, but the ganglioneuromas, themselves, are all benign.

Benign fibroblastic polyps/perineuriomas

These are incidental lesions detected in adult patients undergoing screening colonoscopy. As such, the mean age in reported series ranges from 56 to 64 years.31 They present as small, solitary, asymptomatic polyps (size range, 0.2 to 1.5 cm) usually encountered in the rectosigmoid colon. The polyps consist of an expansion of the lamina propria by a bland, monomorphic spindle cell population with abundant pale eosinophilic cytoplasm focally arranged in a concentric fashion around vessels and crypts. There is no mitotic activity or necrosis. Some are intimately admixed with serrated polyps (Figure 4b), (either sessile serrated adenomas or hyperplastic polyps), which allows authors to discuss ‘epithelial stromal interactions’, an excellent catchphrase that still has little meaning.32, 33, 34

On immunohistochemistry, these are often ‘vimentin-only’ lesions, lacking CD31, S100, CD117/c-kit, Bcl-2, and desmin. As most can be shown to express at least one perineurial marker (EMA, claudin-1, and glucose transporter-1), probably lesions termed ‘colonic perineuriomas’ are the same as benign fibroblastic polyps33, 34, 35 and a minority of cases displays focal SMA and CD34. The Ki67 index is low at approximately 1%. In one study of 22 cases associated with serrated polyps, the authors detected BRAF and KRAS mutations in 63% and 4% of cases, presumably in the serrated polyp component, respectively.32

Benign fibroblastic polyps are managed by simple polypectomy and require no endoscopic follow-up.

Mucosal Schwann cell hamartomas

Mucosal Schwann cell hamartoma is characterized by a diffuse, ill-defined proliferation of spindle cells within the lamina propria, which surrounds colonic crypts.36 Although predominantly encountered in the rectosigmoid, these polyps may arise anywhere in the colon. They are usually small (1–6 mm) and are typically an incidental finding at colonoscopy. The spindle cells show indistinct cell borders and are bland appearing with elongated or wavy nuclei and ample eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 4c). Mucosal ulceration, nuclear atypia, and mitotic activity are absent. The lesional cells are diffusely immunoreactive with S100 protein. In some cases, rare associated axons may be highlighted with a NFP immunostain. The spindle cells are negative for CD34, GFAP, EMA, SMA, and CD117. The main differential diagnosis is with colonic neurofibroma, an important distinction given its clinical association with NF1. Although histologically very similar, colonic neurofibromas display more cellular heterogeneity with more nuclear variability and varying amount of cytoplasm. By immunohistochemistry, the spindle cells in neurofibromas are only focally immunoreactive with S100 protein, and all contain associated axons, which are highlighted with a NFP immunostain. Unlike neurofibromas and ganglioneuromas, mucosal Schwann cell hamartomas are unassociated with syndromic states. Endoscopic follow-up is not necessary after diagnosis.

Psammomatous melanotic schwannoma

Although this tumor is commonly encountered in the posterior spinal nerve roots, the original description by Carney27 presented 11 examples in the GIT. In his report, the most common location was the stomach (7/11), followed by the esophagus (3/11) and rectum (1/11). Lesions may be seen in the setting of Carney complex. When encountered as a polyp in the GIT, this tumor may cause diagnostic confusion because of its rarity and peculiar histological findings (Figures 5a–f). The polyp typically occupies the mucosa and submucosa and is composed of sheets of bland spindle to polygonal medium-sized cells with moderate-to-abundant pink cytoplasm. Rare cases may have nuclear pleomorphism; this finding is not necessarily indicative of malignancy. Intracytoplasmic pigment is evident scattered throughout the polyp. The nuclei are round to ovoid with visible though not prominent nucleoli (as opposed to the macronucleoli of melanoma). Psammoma bodies are present prominently in some examples but are focal in others. Multinucleated cells and osseous metaplasia may be identified. Tumor cells display strong diffuse S100 protein and also express HMB45 and MelanA, which may lead to the consideration of melanoma. Unlike melanoma, however, malignant cytological features are absent. Additionally, Ki67 proliferation index is low. Though GIST may be a consideration, CD117/ckit immunostain is negative in these tumors. In some cases, the correct diagnosis becomes evident after performing multiple deeper levels if the pigment and/or calcifications are not evident on initial cuts. In general, most psammomatous melanotic schwannomas behave indolently, but rare extraintestinal examples have had a more aggressive clinical course.27 It is unclear if the same applies to examples from the GIT.

Psammomatous melanotic schwannoma. (a) The tumor is seen here occupying the mucosa and submucosa and is composed of bland spindle to polygonal plump, bland cells with moderate amount of pink cytoplasm and visible nucleoli. Note scattered cells with intracytoplasmic brown pigment. (b) Higher magnification shows better nuclear detail. Although nucleoli are evident, they are unlike the macronucleoli typical of melanoma. (c) This high magnification image shows a psammoma body. These were rare in this particular example. Note the scattered intracytoplasmic pigment. (d) A Ki67 immunostain shows a low proliferation index. (e) The lesional cells are immunoreactive with HMB45. (f) A S100 immunostain highlights the lesional cells.

Benign epithelioid nerve sheath tumors

Benign epithelioid nerve sheath tumors are identified at colonoscopy as incidental polyps37 (the mean age in our series was 58.6 years), and most arise in the left colon, attaining a size of up to 1 cm, although we have also rarely encountered larger examples. None of the patients that we have encountered with these tumors has had a known history of neurofibromatosis or MEN IIB.

Histologically, the lesions show an infiltrative growth pattern and are composed of spindled to predominantly epithelioid cells arranged in nests and whorls. The epicenter of the lesion is in the lamina propria with extension to the superficial submucosa although we have also encountered cases that extend into the muscularis propria. The proliferating cells have uniform round-to-oval nuclei with frequent intranuclear pseudoinclusions and eosinophilic fibrillary cytoplasm (Figure 6). Some cases display cystic spaces and a pseudoglandular pattern. No mitoses are seen. If Ki-67 is performed, all have a low proliferative index. These tumors express diffuse S100 protein but lack melanoma markers. They have variable CD34 labeling in supporting cells. Tumors lack CD117 and calretinin, and SM31 shows no intralesional neuraxons.

Mucosal neuromas associated with MEN IIB

When other benign nerve sheath tumors are encountered, the concern is always that the lesion could be a mucosal neuroma. Such tumors are different from gangliomeuromas. Both types of tumors are also a component of MEN IIB/ Sipple syndrome, consisting of mucosal neuromas, pheochromocytoma, mesodermal dysplasia, and medullary thyroid carcinoma. Some patients with MEN IIB present with disfigured lips/mouths as a hint of neural tumors throughout their GITs and others with intestinal obstruction. The neuromas of MEN IIB are true neuromas and are composed of coiled and twisted enlarged nerves in which individual fibers are surrounded by coats of perineurium in manner similar to the appearance of a traumatic neuroma (Figures 7a and b). As such, they are easy to distinguish from various nerve sheath tumors in the differential diagnosis.

Submucosa

Inflammatory Fibroid Polyp

Inflammatory fibroid polyp was described in a series in 1949,38 although there were prior case reports. The present term appeared in the early 1950s.39 The vast majority of these tumors occur in the stomach, but they have been reported throughout the GIT. Most patients are between 60 and 80 years. These polyps are not seen in children. Most are found in the antrum, but other gastric sites are known. Their endoscopic appearance is that of a smooth submucosal lesion that can be pedunculated or sessile with surface ulceration/erosion in about one-third of cases. Presentation is somewhat site-specific, in that small intestinal examples can lead to intussusception40 or obstruction, and gastric examples are found in patients with pain, nausea, and vomiting. Inflammatory fibroid polyps have been reported in a family in which three generations of women have had these ‘Devon polyposis’ lesions.41, 42 These polyps were believed to be reactive in the past, but they are now known to have mutations in the platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA) gene,43 a feature that they share with a subset of GISTs. However, in constrast to GISTs, inflammatory fibroid polyps are always benign. Japanese examples have been found in association with gastric dysplasia/carcinoma, presumably based on coincidence,44 but not Western ones. Patients with small bowel inflammatory fibroid polyps often present with intussusception.40

Histologically (Figures 8a and b), these tumors are well-marginated but nonencapsulated. Although they arise in the submucosa, most examples extend into the overlying mucosa. Inflammatory fibroid polyps are composed of uniform spindled cells, mixed inflammatory cells, and prominent vasculature. The spindle cells have amphophilic cytoplasm and pale nuclei, ranging from ovoid to spindle shape, that display variable collagen deposition. Most examples display a whorled, ‘onion skin’ (Figure 8b) proliferation of the spindle cells around vessels, and all examples are punctuated by abundant background eosinophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. Mitoses are infrequent.

The immunohistochemical and ultrastructural profile of the proliferating cells is that of modified fibroblasts/myofibroblasts, with variable actin but no S100 protein or epithelial markers. Their consistent expression of cyclin D1 and fascin suggests that they have dendritic cell differentiation,45 but their key feature is consistent CD34 reactivity in small tumors, which sometimes disappears in larger examples.44 Inflammatory fibroid polyps lack CD117 expression. In large examples, sarcomas are often considered, but the bland appearance of the proliferating cells and the inflammatory background argue against this interpretation. In some respects, these polyps resemble nodular/proliferative fasciitis, but fasciitis lacks CD34 and is typically strongly actin-reactive.46 Solitary fibrous tumor is also CD34-reactive, but it seldom arises in the GIT and lacks an inflammatory backdrop.

Muscularis propia

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor

GIST is the key entity in the muscularis propria and is well studied and will be addressed only briefly in this discussion.

The stomach is the most common site for GISTs, and they are occasionally diagnosed on mucosal biopsies. Typically, but not invariably, those diagnosed on biopsies are aggressive lesions that have invaded the mucosa. GISTs are mesenchymal tumors arising in the GIT and, occasionally, within the abdomen with no demonstrable GI connection. The availability of specific antibodies, and clarification of their immunohistochemical profile, has facilitated diagnosis. However, careful morphological examination and clinicopathological correlation remain essential for excluding mimics and for assessing likely behavior in this heterogeneous group of neoplasms.

GISTs comprise 5–10% of all sarcomas (for comparison, retroperitoneal=15% and extremity, 42%), and about 25% of GISTs are malignant, representing about 1% of all GI malignancies. GISTs are most common in adults 50–60 years. These tumors vary in differentiation and prognosis, according to their location within the GIT. Esophageal GISTs are rare, but 50–70% involve the stomach; 25–40% affect the small intestine (of which 10–20% arise in the duodenum, 27–37% in the jejunum, and 27–53% in the ileum); and <10% are colorectal (50% colonic, 50% rectal). GIST-type tumors arising in omentum, peritoneum, and retroperitoneum have been identified, comprising 6.7% of the large AFIP series of 1008 GISTs.47

Tumors present with primary mass, pain or bleeding (46%), or metastasis (47%); and two-thirds exceed 5 cm at presentation. Malignant GISTs are rare, with about 5 per million people (compared with 25 per million for soft tissue sarcomas). There is an increased incidence of GISTs, including multiple tumors in the small intestine in patients with NF-1 (possibly associated with interaction between the NF-1 gene product and c-kit). This latter type of GIST is fascinating in that it is KIT wild type (without KIT mutations), but the neoplasms express CD117 (again, a presumed result of an interaction between the NF-1 gene product and c-kit);48 they usually arise in the small bowel rather than the stomach. Also, GIST is occasionally familial (associated with a germline c-kit mutation; see below). Some patients have second cancers, and some epithelioid gastric stromal tumors are associated with PGL and pulmonary chondroma in Carney triad. The newly recognized Carney Stratakis is a dyad; patients have germline mutations of the succinate dehydrogenase subunits B (SDHB), C (SDHC) and D (SDHD) and develop multifocal GISTs and multicentric PGLs.49, 50 The GISTs in these syndromes are quite interesting as they lack staining for SDHB (whereas regular GISTs have it) and lack KIT mutations, features they share with pediatric GISTs51 (Figure 9)

(a) Gastrointestinal stromal tumor, pediatric type. Note the plexiform pattern. This neoplasm was shown to have SDHB loss on immunolabeling. (b) Gastrointestinal stromal tumor, pediatric type. Note the monotonous appearance of the neoplastic cells. (c) Gastric carcinoma. (d) Gastric carcinoma, keratin stain. (e) Gastric carcinoma, DOG1 stain. About a third of gastric adenocarcinomas express DOG1, a potential pitfall in the differential diagnosis of epithelioid gastrointestinal stromal tumor. (f) Epithelioid gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Some examples appear similar to gastric adenocarcinomas although there tends to be less conspicuous nuclear pleomophism (and usually no mucosal component).

Most GISTs are spindle cell tumors with variable palisading, peculiar paranuclear vacuoles, and collagen fibrils. On a practical note, it is epithelioid GISTs that are most likely to cause diagnostic problems on mucosal biopsies, because they are readily mistaken for a host of epithelioid and epithelial neoplasms. It is advisable to perform an immunohistochemical panel in assessing them to include CD117/c-kit, S100 protein (to address melanoma), and a cytokeratin stain to address signet cell carcinoma. The vast majority of GISTs have kit mutations and are CD117/c-kit–stain positive, but about 5% (from all sites) lack kit mutations and many in the c-kit–negative subset have alternate mutations of platelet-derived growth factor-α instead.52, 53, 54 As about 70% of gastric GISTs express CD34, this can also be included in a diagnostic panel. DOG1 (discovered on GISTs1) is another antibody that was discovered using gene expression profiling and is also expressed by most GISTs; it can be a supplement to KIT/CD117 labeling.55, 56, 57 However, an important pitfall is that nearly a third of gastric adenocarcinomas express DOG155 (Figures 9c–e), an issue with epithelioid GIST (Figure 9f) but one usually resolved by noting strong diffuse keratin expression in carcinomas. Another pitfall is that epithelioid GISTs sometimes label with melan-A.58

Gastrointestinal schwannomas

Most gastrointestinal schwannomas arise in the stomach and are centered in the muscularis propria.59 They show a female predominance; the largest series documents nearly a 4:1 female-to-male ratio.59 As they affect the muscularis propria, they are nearly always assumed to be GISTs preoperatively and intra-operatively. These are grossly similar to GISTs, having a fibrotic, rubbery, white-yellow cut surface, and well-circumscribed outline typically without a capsule. The tumor is surrounded by a lymphoid cuff in >90% of the cases. On biopsy or fine needle aspiration, this lymphoid cuff is more likely to be obtained than the underlying mesenchymal lesion, potentially misleading the observer to a diagnosis of lymphoma.60 This lymphoid cuff is also a helpful feature to aid in frozen section diagnosis (Figure 10a).

Gastric schwannoma. (a) The lymphoid cuff is a diagnostic clue on frozen sections even though, like GIST, gastric schwannoma almost always arises in the muscularis propria. (b) The mild nuclear pleomorphism and the scattered background lymphocytes differ from the appearance of GIST, which typically has essentially no inflammatory cells and very monomorphic nuclei. (c) Retroperitoneal schwannoma. The features are those of a nerve sheath tumor. Retroperitoneal schwannomas are the source for diagnostic issues on needle biopsies. (d) Retroperitoneal schwannoma, keratin immunolabeling. This example shows strong diffuse keratin expression. This is a common finding. (e) Retroperitoneal schwannoma, S100 protein.

GIT schwannomas are typically not encapsulated, a feature that distinguishes them from schwannomas in the peripheral nervous system. They can also be plexiform. Diffuse intralesional lymphocytes are seen in all cases (Figure 10b). They are composed of interlacing bundles of spindle cells that are only weakly palisaded. Well-formed Verocay bodies are rare. Occasional cases show epithelioid morphology. Most cases present scattered cells with nuclear atypia, but mitotic activity is low. Areas of myxoid change, xanthoma cells, and vascular hyalinization can be encountered in some examples. Although schwannomas appear quite similar to GISTs, the lymphoid cuff is a tip-off that they are, indeed, schwannian. These tumors are all strongly S100 protein-positive and lack muscle markers and CD117. Unlike GISTs, gastric schwannomas lack KIT and PDGFRA mutations (0/9 cases studied). Few studied cases show multiple copies of chromosomes 22, 2, and 18. NF2 mutations, common is soft tissue schwannomas, are rare in gastric examples. These are benign tumors.

As an aside, an important pitfall that can be encountered in samples obtained by imaging-assisted biopsies is that keratin is commonly expressed in retroperitoneal schwannomas (Figures 10c and e).61

Mesenteric lesions

Most mesenteric lesions are found in the small bowel mesentery, but all of them can affect the gastric mesentery. These include fibromatosis, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, sclerosing mesenteritis (which has overlapping features with retroperitoneal fibrosis/IgG4-related sclerosing diseases), and calcifying fibrous pseudotumor. Their features are summarized in Table 2.

Mesenteric fibromatosis

Mesenteric fibromatosis is probably the commonest among the intra-abdominal fibromatosis group. It usually presents as a slowly growing mass that involves small bowel mesentery or retroperitoneum, where distinction may become extremely difficult from retroperitoneal fibrosis. There are cases associated with pregnancy and Crohn’s disease even though the majority is considered to be secondary to trauma in individuals with the appropriate predisposition. Mesentric fibromatosis in patients with Gardner’s syndrome appears to have a substantially higher recurrence rate than in patients without this syndrome. Gardner’s syndrome is an autosomal dominant familial disease with a female predilection and consists of numerous colorectal adenomatous polyps, osteomas, cutaneous cysts, soft tissue masses, and other manifestations. Gardner’s syndrome is related to FAP, a disorder caused by germline adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene mutations. It is associated with an 8–12% incidence of developing fibromatosis.

Among patients with FAP, intestinal and extra-intestinal neoplasms typically arise through bi-allelic (germline then somatic) inactivation of the APC gene, whereas the corresponding tumors in non-FAP patients occur either through somatic bi-allelic APC inactivation or somatic mutation of a single beta-catenin allele. As the various FAP-associated tumors have been studied, somatic alterations of the APC/beta-catenin pathway have been initially detected in familial examples and then subsequently demonstrated in the sporadic counterparts. The first tumors studied were gastrointestinal adenomas, followed by desmoid tumors, medulloblastomas, childhood hepatoblastomas, gastric fundic gland polyps, and nasopharyngeal angiofibromas, all of which occur more frequently in FAP patients than in controls. It has been estimated that FAP patients in general have an 852-fold increased risk of developing desmoids, typically intra-abdominal lesions.

Mesenteric fibromatoses involve the mesentery, of course, but they often infiltrate into the muscularis propria but seldom into the submucosa or mucosa. Grossly, the tumor is firm with coarse white trabeculation resembling a scar and cuts with a gritty sensation. Microscopically, the lesion is poorly defined with infiltrative margins consisting of spindled fibroblasts separated by abundant collagen. Cells and collagen are organized in parallel arrays. Keloid-like collagen and hyalinization may be so extensive as to obscure the original pattern of the tumor. Scattered thin-walled, elongated, and compressed vessels are usually seen with focal areas of hemorrhage, lymphoid aggregates and, rarely, calcification or chondro-osseous metaplasia. Typically the vessels, though thin-walled, appear conspicuous at scanning magnification (Figure 11a). The nuclei of the proliferating lesion are typically tinctorially lighter than those of the endothelial cells and the smooth muscle cytoplasm in vessel walls is pinker than the surrounding myofibroblastic cytoplasm of the tumor cells. Mitotic figures are infrequent. Mesenteric examples often have a storiform pattern similar to that of nodular fasciitis in the soft tissue of the extremities. As fibromatoses are myofibroblastic, they express actin but usually not desmin or CD34. A caveat concerning mesenteric fibromatosis is that these tumors frequently need to be distinguished from GISTs. Although their features are readily distinguishable on routine H&E-stained slides, pathologists should be aware that fibromatoses may react with some comercially available CD117 antibodies. Staining is typically weaker than that seen with true GISTs, but in doubtful cases, β-catenin staining can be helpful (Figure 11b), as nuclear staining is only seen in desmoids.62, 63

(a) Mesenteric fibromatosis. The pale collagen contrasts with the eosinophilic vascular walls. As such, even though the vessels are small, they are conspicuous. The one in the center gapes open, a feature that is chatracteristic of mesenteric examples. (b) Mesesteric fibromatosis, beta catenin stain. Note that the staining is nuclear. Cytoplasmic staining is not considered positive for diagnosis of fibromatosis.

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory fibrosarcoma)

Although these lesions were originally described as separate entities, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor and inflammatory fibrosarcoma are now recognized as ends of a spectrum of tumors unified by a common molecular profile and grouped together by the WHO.64 Gene fusions involving anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) at chromosome 2p23 have been described. In their original description, these tumors were termed ‘inflammatory fibrosarcoma’.65 They are most common in childhood but with a wide age range. This tumor arises within the abdomen, involving mesentery, omentum, and retroperitoneum (>80% of cases), with occasional cases in the mediastinum, abdominal wall, and liver. Sometimes there are associated systemic symptoms. The tumor can be solitary or multinodular (30%) and up to 20 cm in diameter. The tumors are composed of myofibroblasts and fibroblasts in fascicles or whorls (Figure 12a) and also histiocytoid cells. Pleomorphism is moderate, but mitoses are infrequently seen. There is a variable but often marked inflammatory infiltrate, predominantly plasmacytic but with some lymphocytes, and occasionally neutrophils or eosinophils as well. Fibrosis and calcification can be seen in the stroma. Immunostaining is positive for SMA, and many examples express cytokeratin especially where there is submesothelial extension. By immunohistochemistry, ALK has been detected in about 60–70% of cases, a finding that can be exploited for diagnosis and possibly prognosis (positive cases may have a better prognosis) (Figure 12b). The tumors invade adjacent viscera; occasional examples metastasize and are aggressive but most are treated surgically and have indolent behavior. These lesions are more cellular than sclerosing mesenteritis.

(a) Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. The lesional myofibroblastic cells display prominent nucleoli. (b) Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, ALK immunolabeling. This shows the stellate contours of the myofibroblastic cells to advantage. (c) Sclerosing mesenteritis. This process features sclerosis, inflammation, and fat necrosis. It may display IgG4 immunolabeling in plasma cells but lacks the storiform process of classic IgG4-related fibrosclerosis but may be in a spectrum with it. (d) Sclerosing mesenteritis. Note the dense fibrosis and fat necrosis.

Sclerosing mesenteritis

Sclerosing mesenteritis (also known as mesenteric panniculitis, retractile mesenteritis, liposclerotic mesenteritis, mesenteric Weber–Christian disease, xanthogranulomatous mesenteritis, mesenteric lipogranuloma, systemic nodular panniculitis, inflammatory pseudotumor, and mesenteric lipodystrophy) most commonly affects the small bowel mesentery, presenting as an isolated large mass although about 20% of patients have multiple lesions. The etiology remains unknown though it is assumed to reflect a reparative response although the stimulus is not clear; prior trauma/surgery is usually not reported.

Lesions consist of fibrous bands infiltrating and encasing fat lobules with an associated admixture of inflammatory cells, typically lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils (Figures 12c and d). Sometimes these lesions have prominent IgG4-reactive plasma cells, and they often display a lymphocytic phlebitis pattern akin to that in lymphoplasmacytic pancreatitis and retroperitoneal fibrosis.66 There seems to be some relationship between sclerosing mesenteritis and the family of so-called ‘IgG4-related sclerosing disorders’. However, in contrast to the IgG4-related sclerosing disorders, usually sclerosing mesenteritis does not respond to steroids and is less likely to display prominent IgG4 labeling. IgG4-related disease is characterized by the triad of a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, a storiform pattern of fibrosis, and obliterative phlebitis.67

This process is benign but a minority or affected patients die of complications, such as small bowel obstruction. Disease does not typically progress or recur, and the patients’ symptoms are relieved by resection.

Calcifying fibrous pseudotumor

These tumors were originally described as ‘childhood fibrous tumor with psammoma bodies’. Calcifying fibrous tumor/pseudotumor is a rare benign fibrous lesion. Most soft tissue examples affect children and young adults without gender predilection, whereas visceral examples usually occur in adults. These tumors were originally described in the subcutaneous and deep soft tissues (extremities, trunk, neck, and scrotum) but have subsequently been reported all over the body, notably in the mesentery and peritoneum and pleura (sometimes multiple). Visceral examples may produce site-specific symptoms. Radiographs show well-marginated, non-calcified tumors. Calcifications are apparent on CT and may be thick and band-like or punctuate. On MRI, masses appear similar to fibromatoses, with a mottled appearance and a signal closer to that of muscle than fat. Although examples have followed trauma and occurred in association with Castleman’s disease and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors, the pathogenesis remains unknown.

Grossly, these lesions are well marginated but unencapsulated, ranging in size from <1 to 15 cm. Some show indistinct boundaries with infiltration into surrounding tissues. On occasion, a gritty texture is noted on sectioning, which reveals a firm white lesion. Microscopically, calcifying fibrous tumor consists of well-circumscribed, unencapsulated, paucicellular, hyalinized fibrosclerotic tissue with a variable inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and plasma cells (Figure 13a). Lymphoid aggregates may be present. Calcifications, both psammomatous and dystrophic, are scattered throughout (Figure 12b). Lesional cells express vimentin and FXIIIa but usually lack actins, desmin, FVIII, S100 protein, NFP, cytokeratins, CD34, and CD31. The immunophenotype differs from that of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors in that most calcifying fibrous pseudotumors lack actin and ALK. Occasional lesions have expressed CD34. These tumors are benign; occasional recurrences are recorded.

In addition to the aforementioned entities, occasionally lesions analogous to myositis ossificans are present in the mesentery (heterotopic myositis ossificans).

Summary

In closing, the diagnosis of mesenchymal lesions of the GIT can be simplified if one is familiar with the layer in which they arise (mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, etc). Immunohistochemistry, while helpful in some cases, has its pitfalls, and familiarity with these traps is crucial to avoid diagnostic errors.

References

Miettinen M, Paal E, Lasota J et al. Gastrointestinal glomus tumors: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 32 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:301–311.

Kang G, Park HJ, Kim JY et al. Glomus tumor of the stomach: a clinicopathologic analysis of 10 cases and review of the literature. Gut Liver 2012;6:52–57.

Baek YH, Choi SR, Lee BE et al. Gastric glomus tumor: analysis of endosonographic characteristics and computed tomographic findings. Dig Endosc 2013;25:80–83.

Hur BY, Kim SH, Choi JY et al. Gastroduodenal glomus tumors: differentiation from other subepithelial lesions based on dynamic contrast-enhanced CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011;197:1351–1359.

Mosquera JM, Sboner A, Zhang L et al. Novel MIR143-NOTCH fusions in benign and malignant glomus tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2013;52:1075–1087.

Huppmann AR, Orenstein JM . Opportunistic disorders of the gastrointestinal tract in the age of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Hum Pathol 2010;41:1777–1787.

Braun M . Classics in oncology. Idiopathic multiple pigmented sarcoma of the skin by Kaposi. CA Cancer J Clin 1982;32:340–347.

Reynolds WA, Winkelmann RK, Soule EH . Kaposi's sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study with particular reference to its relationship to the reticuloendothelial system. Medicine (Baltimore) 1965;44:419–443.

Cox FH, Helwig EB . Kaposi's sarcoma. Cancer 1959;12:289–298.

Templeton AC . Kaposi's sarcoma. Pathol Annu 1981;16 (Pt 2):315–336.

Finlay AY, Marks R . Familial Kaposi's sarcoma. Br J Dermatol 1979;100:323–326.

Safai B, Mike V, Giraldo G et al. Association of Kaposi's sarcoma with second primary malignancies: possible etiopathogenic implications. Cancer 1980;45:1472–1479.

Mosam A, Aboobaker J, Shaik F . Kaposi's sarcoma in sub-Saharan Africa: a current perspective. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2009;23:119–123.

Wamburu G, Masenga EJ, Moshi EZ et al. HIV—associated and non—HIV associated types of Kaposi's sarcoma in an African population in Tanzania. Status of immune suppression and HHV-8 seroprevalence. Eur J Dermatol 2006;16:677–682.

Sissolak G, Mayaud P . AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma: epidemiological, diagnostic, treatment and control aspects in sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2005;10:981–992.

Penn I . Kaposi's sarcoma in transplant recipients. Transplantation 1997;64:669–673.

Penn I . Kaposi's sarcoma in immunosuppressed patients. J Clin Lab Immunol 1983;12:1–10.

Beral V, Peterman TA, Berkelman RL et al. Kaposi's sarcoma among persons with AIDS: a sexually transmitted infection? Lancet 1990;335:123–128.

Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin MS et al. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Science 1994;266:1865–1869.

Horenstein MG, Moontasri NJ, Cesarman E . The pathobiology of Kaposi's sarcoma: advances since the onset of the AIDS epidemic. J Cutan Pathol 2008;35 (Suppl 2):40–44.

Kao GF, Johnson FB, Sulica VI . The nature of hyaline (eosinophilic) globules and vascular slits of Kaposi's sarcoma. Am J Dermatopathol 1990;12:256–267.

Folpe AL, Chand EM, Goldblum JR et al. Expression of Fli-1, a nuclear transcription factor, distinguishes vascular neoplasms from potential mimics. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:1061–1066.

Folpe AL, Veikkola T, Valtola R et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 (VEGFR-3): a marker of vascular tumors with presumed lymphatic differentiation, including Kaposi's sarcoma, kaposiform and Dabska-type hemangioendotheliomas, and a subset of angiosarcomas. Mod Pathol 2000;13:180–185.

Fukunaga M . Expression of D2-40 in lymphatic endothelium of normal tissues and in vascular tumours. Histopathology 2005;46:396–402.

Orchard GE, Wilson Jones E, Russell Jones R . Immunocytochemistry in the diagnosis of Kaposi's sarcoma and angiosarcoma. Br J Biomed Sci 1995;52:35–49.

Hammock L, Reisenauer A, Wang W et al. Latency-associated nuclear antigen expression and human herpesvirus-8 polymerase chain reaction in the evaluation of Kaposi sarcoma and other vascular tumors in HIV-positive patients. Mod Pathol 2005;18:463–468.

Carney JA . Psammomatous melanotic schwannoma. A distinctive, heritable tumor with special associations, including cardiac myxoma and the Cushing syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 1990;14:206–222.

Shekitka KM, Sobin LH . Ganglioneuromas of the gastrointestinal tract. Relation to Von Recklinghausen disease and other multiple tumor syndromes. Am J Surg Pathol 1994;18:250–257.

Moon SB, Park KW, Jung SE et al. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-producing ganglioneuromatosis involving the entire colon and rectum. J Pediatr Surg 2009;44:e19–e21.

Rescorla FJ, Vane DW, Fitzgerald JF et al. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-secreting ganglioneuromatosis affecting the entire colon and rectum. J Pediatr Surg 1988;23:635–637.

Eslami-Varzaneh F, Washington K, Robert ME et al. Benign fibroblastic polyps of the colon: a histologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:374–378.

Agaimy A, Stoehr R, Vieth M et al. Benign serrated colorectal fibroblastic polyps/intramucosal perineuriomas are true mixed epithelial-stromal polyps (hybrid hyperplastic polyp/mucosal perineurioma) with frequent BRAF mutations. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:1663–1671.

Groisman G, Amar M, Alona M . Early colonic perineurioma: a report of 11 cases. Int J Surg Pathol 2010;18:292–297.

Groisman GM, Polak-Charcon S . Fibroblastic polyp of the colon and colonic perineurioma: 2 names for a single entity? Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:1088–1094.

Hornick JL, Fletcher CD . Intestinal perineuriomas: clinicopathologic definition of a new anatomic subset in a series of 10 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:859–865.

Gibson JA, Hornick JL . Mucosal Schwann cell ‘hamartoma’: clinicopathologic study of 26 neural colorectal polyps distinct from neurofibromas and mucosal neuromas. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:781–787.

Lewin MR, Dilworth HP, Abu Alfa AK et al. Mucosal benign epithelioid nerve sheath tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:1310–1315.

Vanek J . Gastric submucosal granuloma with eosinophilic infiltration. Am J Pathol 1949;25:397–411.

Helwig E, Ranier A . Inflammatory fibroid polyps of the stomach. Surg Gynecol Obstets 1953;96:355–367.

Liu TC, Lin MT, Montgomery EA et al. Inflammatory fibroid polyps of the gastrointestinal tract: spectrum of clinical, morphologic, and immunohistochemistry features. Am J Surg Pathol 2013;37:586–592.

Allibone RO, Nanson JK, Anthony PP . Multiple and recurrent inflammatory fibroid polyps in a Devon family ('Devon polyposis syndrome'): an update. Gut 1992;33:1004–1005.

Anthony PP, Morris DS, Vowles KD . Multiple and recurrent inflammatory fibroid polyps in three generations of a Devon family: a new syndrome. Gut 1984;25:854–862.

Schildhaus HU, Cavlar T, Binot E et al. Inflammatory fibroid polyps harbour mutations in the platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA) gene. J Pathol 2008;216:176–182.

Hasegawa T, Yang P, Kagawa N et al. CD34 expression by inflammatory fibroid polyps of the stomach. Mod Pathol 1997;10:451–456.

Pantanowitz L, Antonioli DA, Pinkus GS et al. Inflammatory fibroid polyps of the gastrointestinal tract: evidence for a dendritic cell origin. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:107–114.

Montgomery EA, Meis JM . Nodular fasciitis. Its morphologic spectrum and immunohistochemical profile. Am J Surg Pathol 1991;15:942–948.

Emory TS, Sobin LH, Lukes L et al. Prognosis of gastrointestinal smooth-muscle (stromal) tumors: dependence on anatomic site. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:82–87.

Miettinen M, Fetsch JF, Sobin LH et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis 1: a clinicopathologic and molecular genetic study of 45 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:90–96.

Gaal J, Stratakis CA, Carney JA et al. SDHB immunohistochemistry: a useful tool in the diagnosis of Carney-Stratakis and Carney triad gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Mod Pathol 2011;24:147–151.

Stratakis CA, Carney JA . The triad of paragangliomas, gastric stromal tumours and pulmonary chondromas (Carney triad), and the dyad of paragangliomas and gastric stromal sarcomas (Carney-Stratakis syndrome): molecular genetics and clinical implications. J Intern Med 2009;266:43–52.

Gill AJ, Chou A, Vilain R et al. Immunohistochemistry for SDHB divides gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) into 2 distinct types. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:636–644.

Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Demetri GD et al. Kinase mutations and imatinib response in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:4342–4349.

Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Duensing A et al. PDGFRA activating mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science 2003;299:708–710.

Yamamoto H, Oda Y, Kawaguchi K et al. c-kit and PDGFRA mutations in extragastrointestinal stromal tumor (gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the soft tissue). Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:479–488.

Miettinen M, Wang ZF, Lasota J . DOG1 antibody in the differential diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a study of 1840 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:1401–1408.

Liegl B, Hornick JL, Corless CL et al. Monoclonal antibody DOG1.1 shows higher sensitivity than KIT in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors, including unusual subtypes. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:437–446.

Espinosa I, Lee CH, Kim MK et al. A novel monoclonal antibody against DOG1 is a sensitive and specific marker for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:210–218.

Guler ML, Daniels JA, Abraham SC et al. Expression of melanoma antigens in epithelioid gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a potential diagnostic pitfall. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2008;132:1302–1306.

Voltaggio L, Murray R, Lasota J et al. Gastric schwannoma: a clinicopathologic study of 51 cases and critical review of the literature. Hum Pathol 2012;43:650–659.

Rodriguez E, Tellschow S, Steinberg DM et al. Cytologic findings of gastric schwannoma: a case report. Diagn Cytopathol 2014;42:177–180.

Fanburg-Smith JC, Majidi M, Miettinen M . Keratin expression in schwannoma; a study of 115 retroperitoneal and 22 peripheral schwannomas. Mod Pathol 2006;19:115–121.

Bhattacharya B, Dilworth HP, Iacobuzio-Donahue C et al. Nuclear beta-catenin expression distinguishes deep fibromatosis from other benign and malignant fibroblastic and myofibroblastic lesions. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:653–659.

Montgomery E, Folpe AL . The diagnostic value of beta-catenin immunohistochemistry. Adv Anat Pathol 2005;12:350–356.

Fletcher C, Unni K, Mertens FE . World Health Organization Classification of Tumours In: Sohin L (ed). Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. IACR Press: Lyon, France, 2002.

Fletcher C, Bridge J, Hogendoorn PC et al WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone Bosman F, Jaffe E, Lakhani S, Ohgaki H (eds)., WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

Chen TS, Montgomery EA . Are tumefactive lesions classified as sclerosing mesenteritis a subset of IgG4-related sclerosing disorders? J Clin Pathol 2008;61:1093–1097.

Deshpande V, Zen Y, Chan JK et al. Consensus statement on the pathology of IgG4-related disease. Mod Pathol 2012;25:1181–1192.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Voltaggio, L., Montgomery, E. Gastrointestinal tract spindle cell lesions—just like real estate, it’s all about location. Mod Pathol 28 (Suppl 1), S47–S66 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2014.126

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2014.126

This article is cited by

-

Isolated intestinal Ganglioneuromatosis: case report and literature review

Italian Journal of Pediatrics (2021)

-

A Case of Glomus Tumor Mimicking Neuroendocrine Tumor on 68 Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT

Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (2021)