Abstract

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is characterized by the inv12(q13q13)-derived NAB2–STAT6 fusion, which exhibits variable breakpoints and drives STAT6 nuclear expression. The implications of NAB2–STAT6 fusion variants in pathological features and clinical behavior remain to be characterized in a large cohort of SFTs. We investigated the clinicopathological correlates of this genetic hallmark and analyzed STAT6 immunoexpression in 28 intrathoracic, 37 extrathoracic, and 23 meningeal SFTs. These 88 tumors were designated as histologically nonmalignant in 75 cases and malignant in 13, including 1 dedifferentiated SFT. Eighty cases had formalin-fixed and/or fresh samples to extract assessable RNAs for RT-PCR assay, which revealed NAB2–STAT6 fusion variants comprising 12 types of junction breakpoints in 73 fusion-positive cases, with 65 (89%) falling into 3 major types. The predominant NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2 (n=33) showed constant breakpoints at the ends of involved exons, whereas the NAB2ex6–STAT6ex16 (n=16) and NAB2ex6–STAT6ex17 (n=16) might exhibit variable breakpoints and incorporate NAB2 or STAT6 intronic sequence. Including 73 fusion-positive and 7 CD34-negative SFTs, STAT6 distinctively labeled 87 (99%) SFTs in nuclei, exhibited diffuse reactivity in 73, but did not decorate 98 mimics tested. In seven fusion-negative cases, 6 were STAT6-positive, suggesting rare fusion variants not covered by RT-PCR assay. Regardless of histological subtypes, intrathoracic SFTs affected older patients (P=0.035) and tended to be larger in size (P=0.073). Compared with other variants, NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2/4 fusions were significantly predominant in the SFTs characterised by intrathoracic location (P<0.001), older age (P=0.005), decreased mitoses (P=0.0028), and multifocal or diffuse STAT6 staining (P=0.013), but not found to correlate with disease-free survival. Conclusively, STAT6 nuclear expression was distinctive in the vast majority of SFTs, including all fusion-positive tumors, and exploitable as a robust diagnostics of CD34-negative cases. Despite the associations of NAB2–STAT6 fusion variants with several clincopathological factors, their prognostic relevance should be further validated in large-scale prospective studies of SFTs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Solitary fibrous tumor is a relatively uncommon mesenchymal tumor of fibroblastic differentiation in adults, which was prototypically described as pleura-based1 but is currently known to ubiquitously affect any anatomic site.2, 3 Most solitary fibrous tumors are clinically indolent, whereas the overall rate of local recurrences and/or metastases is estimated to be ~10–15%.4, 5 Although the extrapleural solitary fibrous tumors have been reported to behave more aggressively, there were discordant opinions among various series.3, 4, 6, 7, 8 Conventional solitary fibrous tumor is characterized by patternless proliferation of spindly tumor cells with alternating cellularity, varying fibrosclerotic to myxoid stroma, and elaborate staghorn vessels with or without perivascular hyalinization.3, 9 However, the variations in the cellular components, mitotic activity, and stromal matrix constitute a broad clinicopathological spectrum of solitary fibrous tumors, which not only poses difficulties in predicting clinical aggressiveness but also brings about histological subtypes challenging in distinguishing from other benign or malignant mesenchymal neoplasms.3, 9, 10 In the past, solitary fibrous tumors were diagnosed by combined assessment of clinicopathological context and immunohistochemical markers with imperfect sensitivity and specificity, such as CD34, which is not expressed in 5–10% of histologically characteristic solitary fibrous tumors.3, 6, 9, 10 In the era of advocating minimally invasive needle biopsy for deep-seated mesenchymal neoplasms, it is highly desirable to have novel robust biomarker(s) or molecular testing to aid in the diagnosis of difficult cases.

Recently, massive parallel sequencing studies on solitary fibrous tumors have enabled the groundbreaking discovery of an intrachromosomal inversion-derived gene fusion, which juxtaposes the neighboring NGFI-A binding protein 2 (NAB2) gene and signal transducer and activator of transcription 6, interleukin-4 induced (STAT6) gene on 12q13.11, 12, 13 As an initiating pathognomonic event in both benign and malignant solitary fibrous tumors, NAB2–STAT6 fusion identified in this breakthrough incorporated solitary fibrous tumors into the long growing list of mesenchymal neoplasms defined by disease-specific gene fusions.14

Alternative fusion partners or exon composition types of some gene fusion-defined sarcomas may modestly impact on clinical and biological variations.15, 16, 17 Intriguingly, recent studies revealed significant preponderance of the NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2/3 variants over NAB2ex6–STAT6ex16/17 variants in pleuropulmonary solitary fibrous tumors, and the former were associated with extensive fibrosclerotic stroma, favorable histological variables, and perhaps indolent behavior.18, 19 This finding indicated that determining NAB2–STAT6 exon composition types in solitary fibrous tumors is of potential clinicopathological interest. However, the chimeric NAB2–STAT6 fusion transcript exhibits highly variable breakpoints across 5′ exons of NAB2 and 3’ exons of STAT6, hence, rendering reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay more cumbersome to perform using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue.2, 11, 12, 13, 18 As the resultant NAB2–STAT6 fusion protein drives the nuclear entry of STAT6,11 several groups exploited this biological character of STAT6 nuclear expression to facilitate the discrimination between solitary fibrous tumors and histological mimics, without resorting to RT-PCR.10, 20, 21 However, Doyle et al22 have notified that STAT6 nuclear expression is driven by gene amplification and coamplified with CDK4 and MDM2 in a minor subset of dedifferentiated liposarcomas, a treacherous caveat liable to result in misdiagnosis of solitary fibrous tumors, given occasional presence of solitary fibrous tumor-like histology in dedifferentiated liposarcomas.23, 24

Aiming at better characterization of the relevance of STAT6 nuclear entry and NAB2–STAT6 fusion variants, we have comparatively analyzed the STAT6 immunoexpression and NAB2–STAT6 exon composition types and correlated the findings with clinicopathological features of a large cohort of recently accessioned thoracic, extrathoracic, and meningeal solitary fibrous tumors.

Materials and methods

Patient Cohort

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, which granted exemption of informed consent for tissue procurement after an anonymous unlinked process (102-3703B, l02-3843B). To perform RT-PCR assay, the personal consult file (HYH) and archives of Chang Gung Hospitals in Kaohsiung and Taoyuan were searched for cases coded as solitary fibrous tumor, hemangiopericytoma, and giant cell angiofibroma with primary or recurrent formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens resected after 2009 and/or available fresh tissues. After a central review of hematoxylin eosin-stained slides to exclude potential histological mimics, 88 diagnostically confirmed solitary fibrous tumors formed the study cohort for further clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and molecular analyses, including 84 with only formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded materials, 2 with only cryopreserved fresh tissues, and 2 with both fresh and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. As shown in the Table 1, there were 28 intrathoracic, 37 extrathoracic, and 23 meningeal cases. Their histological features were regarded as conventional, cellular, atypical, malignant, or dedifferentiated based on the WHO tumor classification of Tumors of Soft tissue as detailed by Doyle et al3, 10 Briefly, it requires >4 mitoses per 10 high-power fields (HPFs) to designate malignant solitary fibrous tumors, with or without hypercellularity, nuclear atypia, tumor necrosis, and infiltrative borders. Those with apparent nuclear atypia but ≤4 mitoses/10 HPFs were classified as atypical solitary fibrous tumors. Not fulfilling the criteria of malignant or atypical solitary fibrous tumors, cellular variants were reminiscent of so-called hemangiopericytomas, and characterized by diffusely increased cellularity with scant collagenous stroma. For the simplification in statistics, we dichotomized solitary fibrous tumors into two groups (Table 1), namely histologically nonmalignant and malignant, with the conventional, cellular, and atypical variants jointly categorized into the former group. Clinicopathological and follow-up data, such as age at presentation, tumor sizes, and the dates of local recurrences and metastases, were obtained by reviewing the electronic medical charts. To examine the specificity of STAT6 nuclear expression, we recruited a wide variety of 98 benign or malignant mesenchymal neoplasms listed in Supplementary Table S1 as controls, which principally presented with prominent staghorn vasculature and underwent molecular confirmation in translocation-associated tumor types.

Immunohistochemistry

To perform STAT6 immunohistochemistry, one representative formalin-fixed tissue block was recut at 3-μm thickness from each solitary fibrous tumors and control case. The recut sections were microwaved in citrate buffer at pH 6.0 for 15 min and incubated with a primary rabbit monoclonal antibody against STAT6 (1:100, YE361, GeneTex), followed by detection with Envision Plus system (DAKO). The staining intensity (0, no staining; 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, strong) and extent (0, <1%; 1, 1–25%; 2, 26–50%; 3, 51–75%; 4: >75%) were recorded for each case, with only nuclear staining being considered positive. CD34 stain was performed in 82 cases at the initial diagnosis and reappraised using the same scoring method for STAT6 assessment, except for evaluating only the cytoplasmic staining. Two pathologists (HCT) and (ICC) independently scored the immunohistochemical findings without knowledge of patient outcomes and molecular testing results. For cases with discrepancies between two observers, the senior author (HYH) joined the reading to reach a consensus by a majority vote under multiheaded microscopy.

RT-PCR

Regardless of the tissue sources, detection of NAB2–STAT6 fusion transcript by RT-PCR was performed in all 88 cases with available formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, and/or fresh materials. Briefly, RNA was extracted from fresh and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues by RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and RecoverAll Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Ambion), respectively. Following the manufacturers’ instructions, 2 μg of total RNA from each fresh or formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sample was used to synthesize the first-strand cDNA using ImPromII RT System (Promega). The subsequent PCR was performed by Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) in a final reaction volume of 25 μl, using 2 μl of cDNA product and newly designed primer sets I to VIII to cover most of the fusion transcripts with various previously reported exon compositions11, 13, 18, 19 as listed in Supplementary Table S2. The thermal protocol started with 95 °C for 5 min for denaturation, followed by 38 cycles of amplification for formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens and 35 cycles for fresh specimens, which consisted of 95 °C for 30 s, a touchdown temperature gradient from 62 to 59 °C in cycles 1 to 4 and 58 °C in the remaining cycles for 30 s, and 72 °C for 45 s, and a terminal elongation step of 72 °C for 10 min. Housekeeping phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) gene was used as indicators of RNA quality. Negative controls without cDNA template or RT enzyme were amplified in parallel to ensure no false-positive findings. The PCR products were separated on 2.0% agarose gels with ethidium bromide and visualized under UV illumination. In selected cases harboring major NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2, NAB2ex6–STAT6ex16, and NAB2ex6–STAT6ex17 fusion variants, their PCR-amplified products were validated by Sanger sequencing (Applied Biosystems 3730 DNA Analyzer) to serve as the positive controls. In these sequenced reference cases, there was neither interruption of the integrity of juxtaposing exons at the breakpoints nor incorporation of intronic sequences of NAB2 and STAT6 genes, hence, yielding PCR products of fixed amplicon sizes for comparison in the subsequent assays. All discrete bands of other possible fusion variants were all similarly determined for their breakpoints and exon compositions using Sanger sequencing and analyzed by the BLAST provided by the National Center for Biotechnology Information. The NAB2 and STAT6 exons were numbered as previously reported according to the Ensembl platform (www.ensembl.org/).19

Statistical Analysis

Agreement on the extent of STAT6 nuclear expression between observers was evaluated by κ statistics. Associations and comparisons of STAT6 immunoexpression or NAB2–STAT6 fusion variants with various clinicopathological parameters were evaluated by the χ2- or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables as appropriate. The end point evaluated was disease-free survival. In univariate survival analysis, Kaplan–Meier curves were plotted and the difference between groups compared by the log-rank test. For all analyses, two-sided tests of significance were used with P< 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Clinicopathological Features and Follow-up

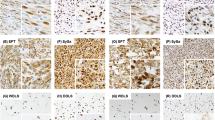

As tabulated in Table 1, there were 49 male and 39 female patients with solitary fibrous tumors, ranging widely in age from 13 to 82 years (median, 51 years; mean, 50 years). Patients with intrathoracic solitary fibrous tumors ranked the oldest, who were significantly older than those with extrathoracic and meningeal tumors (P=0.035). Of 81 solitary fibrous tumors with known size (range, 0.8–27.5 cm), intrathoracic cases tended to present with a larger size than the extrathoracic and meningeal counterparts (P=0.073). Histologically, these 88 cases were categorized into 75 nonmalignant solitary fibrous tumors, including 53 conventional (Figures 1a1 and b1) or cellular (Figure 1c1), 22 atypical (Figure 1d1) variants, and 13 malignant solitary fibrous tumors (Figure 1e1), including 1 dedifferentiated variant (Figure 1f1). In the conventional/cellular solitary fibrous tumors, 5 cases (orbits, 2; trunk, 2; nasal cavity, 1) exhibited focal or prominent giant cell angiofibroma-like histology with multinucleated cells surrounding pseudoangiomatous spaces (Figure 1g1), 2 fat-forming solitary fibrous tumors contained mature adipocytes (Figure 1h1), and 1 case had multinodular growth of elaborate vessels with varying calibers, reminiscent of that seen in soft-tissue angiofibroma (Figure 1i1). In the dedifferentiated solitary fibrous tumor, there was an abrupt interface between the conventional hypocellular solitary fibrous tumor and the dedifferentiated component featuring solid sheets of closely packed, small hyperchromatic round cells with increased mitoses and geographic necrosis (Figure 1f1). Tumor location was neither associated with histological subtypes nor with mitotic rates.

Histological spectrum and STAT6 nuclear reactivity in various subtypes of solitary fibrous tumors. (a1) A conventional pleural solitary fibrous tumor, harboring NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2 fusion, exhibits alternating cellularity of bland spindle cells and staghorn vessels with perivascular hyalinization. (b1) Another pleural solitary fibrous tumor, also harboring NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2 fusion, shows diffuse hypocellularity and sclerotic matrix with staghorn vessels and thick collagen fibers (inset). (c1) A cellular meningeal solitary fibrous tumor, harboring NAB2ex6–STAT6ex17 fusion, shows closely packed oval tumor cells around thin-walled capillaries in the paucity of collagen fibers. (d1) A pleura-based atypical solitary fibrous tumor, harboring NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2 fusion, exhibits storiform or fascicular growth of at least moderately atypical spindle cells without increased mitoses (inset). (e1) A histologically malignant meningeal solitary fibrous tumor, harboring NAB2ex6–STAT6ex16 fusion, is characterized by hypercellular proliferation of round to oval tumor cells, with a mitotic count >4 per 10 HPFs (inset, increased mitoses). (f1) A dedifferentiated solitary fibrous tumor of the pelvic cavity shows an abrupt interface between the conventional (left upper) and dedifferentiated (right lower) components, with sheet-like growth of high-grade small round cells in the latter (inset) and identical NAB2ex6–STAT6ex16 fusion being detected in both components. (g1) An inguinal giant cell angiofibroma-like solitary fibrous tumor, harboring NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2 fusion, displays small cracking spaces surrounded by multiple multinucleated giant cells. (h1) A cellular fat-forming solitary fibrous tumor shows aggregates of mature adipocytes among tumor cells. (i1) A soft-tissue angiofibroma-like solitary fibrous tumor of the back exhibits scattered spindle cells within a rich vascular network comprising vague lobules of small capillaries with peripheral hyalinized vessels. (a2–i2) The corresponding STAT6 immunostains of Figures a1-i1 reveal diffuse strong nuclear labeling in most cases, whereas moderate intensity was observed in the representative atypical (d2) and dedifferentiated (f2) variants.

Follow-up data were available in 79 cases with a median duration of 22.8 months (1.9 years; range, 0.1–12.4 years). At last follow-up, 67 patients were doing well after tumor resection with no evidence of disease, including 3 meningeal cases receiving postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy. Eight patients were alive with tumors, including six with cellular meningeal solitary fibrous tumors having persistent or recurrent diseases, one with a malignant meningeal solitary fibrous tumor developing four local recurrences, and one with a malignant pleural solitary fibrous tumor exhibiting multiple pulmonary metastases. Three patients were dead of tumors, including one with a malignant meningeal solitary fibrous tumor afflicted by uncontrollable local recurrences and two with malignant pleural solitary fibrous tumors developing metastases to the bones and lungs. The only one patient dead of unrelated cause had a 2.2-cm conventional solitary fibrous tumor on the back. Compared with the nonmeningeal counterpart, the meningeal location was the only factor marginally associated with worse disease-free survival (Figures 2a, P=0.0554), whereas other variables were not significant regarding this endpoint on account of the relatively shorter follow-up time and fewer adverse events.

(a) In the log-rank prognostic analyses, the meningeal location is the only clinicopathological factor that is marginally related to worse disease-free survival. (b) Regarding disease-free survival, solitary fibrous tumors with NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2/4 fusions are not prognostically different from those with all other fusion variants.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemically, CD34 was positive in 74 out of 82 cases (90%). There was excellent concordance between two pathologists in the interpretation of nuclear STAT6 immunoexpression (κ=0.872, 95% CI: 0.735–1.000). As seen in Figure 1a2–i2 and Table 1, STAT6 distinctively decorated the nuclei with moderate to strong intensity in 87 (99%) of 88 solitary fibrous tumors tested, the staining extent of which was multifocal (3+) or diffuse (4+) in 73 (83%) cases. Of the eight CD34-negative solitary fibrous tumors, seven cases exhibited STAT6 nuclear expression, being focal in three and multifocal/diffuse in four. There was no statistically significant difference in the staining extent among intrathoracic, extrathoracic and meningeal solitary fibrous tumors. Moreover, STAT6 nuclear expression was observed in none of the 98 histologic mimics tested, except for nonspecific cytoplasmic staining noted in few cases.

Determination of NAB2–STAT6 Fusion Variants and Their Clinicopathological and Immunohistochemical Correlations

In the RT-PCR assay, NAB2–STAT6 fusion variants with considerable heterogeneity in exon compositions were successfully detected in 73 samples by using 8 primer pairs (Supplementary Table S2, Figures 3 and 4), which revealed 12 types of junction breakpoints as a whole. The breakpoints were identical between cryopreserved primary tumors and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded recurrent lesions in two cases and between the conventional and dedifferentiated components in one dedifferentiated solitary fibrous tumor. Eight cases were noninformative because of RNA degradation as indicated by nonamplifiable PGK mRNA, whereas seven cases with amplifiable PGK showed no detectable NAB2–STAT6 gene fusion using the same primer pairs. NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2 was present in 33 cases, representing the most frequent variant (Figure 3). The functionally similar NAB2ex6–STAT6ex16 and NAB2ex6–STAT6ex17 variants were present in 16 cases each, both equally ranking the second (Figure 3). Notably, one solitary fibrous tumor with NAB2ex6–STAT6ex16 additionally incorporated 39-bp intronic sequence of NAB2 fused in frame to the 5′-end of STAT6 exon 16, and another solitary fibrous tumor with NAB2ex6–STAT6ex17 had an intervening 18-bp intronic sequence of STAT6 fused in frame to the 5′-end of STAT6 exon 17 (Figure 4b2). Other unusual types of gene fusions were NAB2ex3–STAT6ex19 and NAB2ex7–STAT6ex2 in two cases each, and NAB2ex3–STAT6ex2, NAB2ex4–STAT6ex4, NAB2ex6–STAT6ex3, and NAB2ex6–STAT6ex18 in one case each.

A schematic diagram of frequency distribution and exon compositions of various NAB2–STAT6 fusion patterns in 73 successfully analyzed solitary fibrous tumors using RT-PCR. Note exons 7–15 of STAT6 are incompletely illustrated and indicated by a hatched segment. ‡, breakpoints within the truncated exons; Italic I, NAB2 or STAT6 intronic sequence.

NAB2–STAT6 fusion variants in solitary fibrous tumors identified by RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing. (a) In the gel electrophoresis of PCR products, various NAB2–STAT6 fusions with heterogeneous exon compositions in representative tumors are identified using eight primer pairs (upper, I–III; middle, IV–VIII). The seven solitary fibrous tumors negative for detection of NAB2–STAT6 fusion by RT-PCR shows amplifiable housekeeping PGK transcript (lower). *Fusion transcript validated by direct sequencing. ‡, breakpoints within the truncated exons. The red arrow in lane 18 indicates the in-frame fusion product of the 2 bands obtained. (b1,2) Direct Sanger sequencing reveals 12 different junction breakpoints in representative cases as labeled using the lane numbers on the gels in (a). Of note, the case in lane 10 demonstrates a stretch (18 bp) of STAT6 intronic sequence between the 3′-end of NAB2 exon 6 and 5′-end of STAT6 exon 17, whereas the case in lane 15 harbors a stretch (39 bp) of NAB2 intronic sequence between the 3′-end of NAB2 exon 6 and 5′-end of STAT6 exon 16. ‡, breakpoints within the truncated exons.

As seen in the Table 2, patients with solitary fibrous tumors harboring the NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2/4 transcripts were significantly older in the mean age at presentation (P=0.005, 54.03 years vs 46.28 years), indicating possible age-related variability in the exon compositions of NAB2–STAT6 fusion transcripts. The NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2/4 variants were strongly associated with the intrathoracic solitary fibrous tumors (P<0.001), in contrast to the dominance of all other fusion types in both extrathoraic and meningeal solitary fibrous tumors. Furthermore, solitary fibrous tumors with NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2/4 were significantly associated with lower mitotic rates (P=0.028) and multifocal/diffuse STAT6 nuclear reactivity (P=0.013), while 9 of 39 cases with other fusion variants displayed focal nuclear STAT6 expression only. There was no prognostic difference in disease-free survival between solitary fibrous tumors harboring NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2/4 and other fusion variants (Figures 2b, P=0.2175).

Discussion

Gene fusions in bone and soft-tissue neoplasms are currently known to derive from chromosomal translocations, whereas the underlying differences in the exon compositions or fusion partners may variably dictate the tumor biology in terms of morphology and clinical behavior.15, 16, 17, 25, 26 For instance, patients with metastatic alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas harboring PAX3–FOXO1 fare worse than those with PAX7–FOXO1-positive metastatic tumors.16 In synovial sarcomas, there are strong correlations between SSX2 rearrangements and monophasic histology and between SSX1 rearrangements and preference of extremities in tumor location.15, 25, 27 In contrast, there is at most modest, if any, prognostic difference between heterogeneous fusion variants (EWSR1–FLI1 type 1 fusion vs others) in Ewing sarcomas.17, 26, 28

Notably, few mesenchymal tumor types with specific gene fusions discovered to date do not exhibit typical chromosomal translocations visible at the karyotypic level.11, 13, 14, 29, 30 Instead, this minor subset harbors previously unrecognized intrachromosomal inversion(s), eg, inv(12) (q13q13) in solitary fibrous tumors,11, 13 or interstitial deletion(s), eg del(8)(q13.3q21.1), in mesenchymal chondrosarcomas.30 In these tumors, the rearranged partner genes have been recently identified by sophisticated profiling or sequencing technology to characterize disease-defining molecular hallmarks.11, 13, 30 Of these, the NAB2–STAT6 fusion as the main molecular driver of solitary fibrous tumors is unique among currently known gene fusions in mesenchymal tumors for its difficulty in applying FISH to aid in diagnosis. This is ascribed to the close proximity of rearranged NAB2 and STAT6 genes that precludes adequate resolution of florescent signals.11, 13 To make matters complicated, the tremendous variability in both NAB2 and STAT6 breakpoints even exceeded the complexity reported in the EWSR1–FLI1 fusion of Ewing sarcomas28 and in the FUS–CREB3L1/2 fusions of low-grade fibromyxoid sarcomas,31 making the delineation of exon compositions in the resultant fusion variants more cumbersome and requiring several RT-PCR assays to cover the less prevalent variants.11, 13, 18, 19 Given the nuclear entry of STAT6 driven by the NAB2–STAT6 gene fusion, several studies have reported the roles of STAT6 nuclear expression both in authenticating CD34-negative solitary fibrous tumors and in distinguishing solitary fibrous tumors from histological mimics featuring staghorn vasculature and/or CD34 reactivity.10, 20, 21 In this study, STAT6 exhibited distinctive nuclear labeling in seven of eight CD34-negative solitary fibrous tumors with typical histology, indicating its better sensitivity. In addition, we experienced a peculiar CD34-positive tumor with a rich, but potentially misleading, vascular network of lobules of capillaries and dilated staghorn vessels, which closely mimicked a soft-tissue angiofibroma but turned out to be a solitary fibrous tumor with diffuse STAT6 nuclear expression.32 Except for nonspecific cytoplasmic staining found randomly in few cases, the diagnostic specificity of STAT6 was also exemplified in 98 histological mimics, which embraced 37 benign or malignant mesenchymal tumor types and lacked STAT6 nuclear expression in every sample tested. Some tumor types in the negative control group had never been previously examined for STAT6, such as superficial angiomyxoma, juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, inflammatory fibroid polyp, angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma, and spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma.

The advantage of STAT6 immunostaining in sparing laborious RT-PCR assays may raise the question about necessity of ascertaining the exon compositions of individual fusion variants in solitary fibrous tumors. Prior expression profiling analysis indicated a homogenous transcriptional signature of solitary fibrous tumors, which clustered in a distinct genomic group from other sarcoma types and was independent of anatomic sites.33 However, this study was published before the identification of NAB2–STAT6, lacking the clustering analysis for various fusion types to interrogate whether there are different transcriptional repertoires of downstream target genes regulated by NAB2–STAT6. Therefore, it remains desirable to better characterize whether the intrinsic genetic difference of this molecular hallmark may dominate the observed clinicopathological variability in solitary fibrous tumors from various primary locations. To elucidate the potential impact of individual NAB2–STAT6 fusion variants, we adopted multiple primer pairs to determine exon compositions for robust correlations with clinical, pathological, and STAT6 immunohistochemical finding of solitary fibrous tumors. Since fresh tumor samples are not always available, this attempt was most easily attainable by analyzing a large series of recently obtained formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples from various representative locations as performed in this study. Given the potential limitations of UV illumination for detecting small changes in transcript size, we only determined NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2, NAB2ex6–STAT6ex16, and NAB2ex6–STAT6ex17 with constant breakpoints at the exonic junction ends of both NAB2 and STAT6 genes by comparing the product sizes with known sequenced controls. When leaving aside eight cases with nonanalyzable degraded RNAs, our overall positive detection rate of NAB2–STAT6 fusion was 91% (73/80), comparable to 92% (48/52) in a recent study.19 Of the remaining seven cases, six were diffusely positive for STAT6 nuclear expression, but undetectable for NAB2–STAT6 fusion. This discrepancy between the NAB2–STAT6 chimeric transcript and STAT6 protein in expression might be attributable to complex rearrangements involving other exons beyond the coverage of our primer combination or potential existence of an unrecognized alternative partner gene other than NAB2.

Compared with prior data,19 we yet obtained a slightly higher prevalence rate (89% vs 75%) of three major fusion variants, namely NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2, NAB2ex6–STAT6ex16, and NAB2ex6–STAT6ex17, among all successfully analyzed cases. In addition, solitary fibrous tumors harboring NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2/4 not only presented with an older age and a predilection for the intrathoracic region but also exhibited significantly lower mitotic activity in our series. These findings reinforced the presumption claimed by Barthelmeß et al19 that solitary fibrous tumors harboring NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2/3/4 were distinct from those with other fusion types in several clinicopathological aspects. In their study, solitary fibrous tumors with NAB2ex6–STAT6ex16/17 more frequently exhibited cellular histology with scanty collagenous stroma, a predominance of nonpleuropulmonary sites, younger patient ages, and perhaps more aggressive behavior. As summarized in Table 3, ~40% (19/48) of cases with informative RT-PCR finings in the series of Barthelmeß lacked information of follow-up durations, and the prognostic comparison for different fusion variants was not evaluated by the ordinary log-rank method. Similar to the series of Akaike et al18 (Table 3), we could not significantly distinguish between genetic subsets of solitary fibrous tumors with different exon compositions in disease-free survival, leaving the real prognostic impact of NAB2–STAT6 fusion variants undetermined. Admittedly, the desired optimization of RT-PCR in detecting NAB2–STAT6 fusion variants necessitated the extraction of most recently resected formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens with inherent limitation in the length of follow-up duration and the number of adverse events, which may account for the absence of significant prognostic impact of increased mitoses and malignant histology in our series. Moreover, among the three series for comparison in Table 3, our cohort notably contained the highest percentage of solitary fibrous tumors classified as nonmalignant with the lowest mean mitotic rate, conceivably requiring even longer follow-up time for adverse events to occur.

In our series, we found that the intrathoracic solitary fibrous tumors tended to be larger in size and presented with a significantly older age than the extrathoracic and meningeal counterparts. This location-associated variability could be partly explained by the fact that the presentation of intrathoracic solitary fibrous tumors was usually an incidental discovery on chest X-ray or CT with a longer preoperative duration to form a sizable mass or become symptomatic at the older age. In univariate analysis, only the meningeal location showed a marginal trend toward association with worse disease-free survival, which might be attributable to the difficulty in achieving complete resection of solitary fibrous tumors in this anatomical region.34 However, the possible intrinsic biological effect of the preponderant NAB2ex6–STAT6ex16/17 fusions (17 of 19) in meningeal solitary fibrous tumors could not be totally excluded at this point. Therefore, it is of potential interest to elucidate the prognostic relevance of NAB2–STAT6 gene fusions in a future large-scale study comprising prospectively accrued solitary fibrous tumors with molecular characterization at diagnsosis, balanced proportions of tumors from various anatomic regions, and longer subsequent follow-up. For the part of molecular testing, we propose to first discriminate the NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2/3 from other non-NAB2ex4-fused fusion patterns using primer pair I, followed by simultaneous detection of NAB2ex–STAT6ex16 and NAB2ex6–STAT6ex17 using separate primer pairs III and IV, and then specific determination of rare fusion variants using individual primer pairs as appropriate for negative cases.

In conclusion, our immunohistochemical and molecular analyses of solitary fibrous tumors reinforce the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of STAT6 nuclear immunoexpression in the differential diagnosis of histological mimics. We further delineate the common and rare NAB2–STAT6 fusion variants in solitary fibrous tumors, of which the NAB2ex4–STAT6ex2, NAB2ex6–STAT6ex16, and NAB2ex6–STAT6ex17 represent the three major fusion variants. The large case number of this study enables more robust correlation between the clinicopathological features and molecular data, identifying that those NAB2ex4-fused solitary fibrous tumors are distinct from non-NAB2ex4-fused counterparts in many clinicopathological aspects, such as locations, ages, and mitotic activity. However, the prognostic relevance of NAB2–STAT6 fusion variants should be further validated in future large-scale prospective studies with longer follow-up duration.

References

Klemperer P, Coleman BR . Primary neoplasms of the pleura: a report of five cases. Arch Pathol 1931;11:385.

Brunnemann RB, Ro JY, Ordonez NG et al. Extrapleural solitary fibrous tumor: a clinicopathologic study of 24 cases. Mod Pathol 1999;12:1034–1042.

Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Lee J-C, Extrapleural solitary fibrous tumour In: Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW et al. (eds). WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. IARC: Lyon, France, 2013, pp 80–82.

Demicco EG, Park MS, Araujo DM et al. Solitary fibrous tumor: a clinicopathological study of 110 cases and proposed risk assessment model. Mod Pathol 2012;25:1298–1306.

Gold JS, Antonescu CR, Hajdu C et al. Clinicopathologic correlates of solitary fibrous tumors. Cancer 2002;94:1057–1068.

Hasegawa T, Matsuno Y, Shimoda T et al. Extrathoracic solitary fibrous tumors: their histological variability and potentially aggressive behavior. Hum Pathol 1999;30:1464–1473.

Nielsen GP, O'Connell JX, Dickersin GR et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of soft tissue: a report of 15 cases, including 5 malignant examples with light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural data. Mod Pathol 1997;10:1028–1037.

van Houdt WJ, Westerveld CM, Vrijenhoek JE et al. Prognosis of solitary fibrous tumors: a multicenter study. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:4090–4095.

Fletcher CDM, Gibbs A, Solitary fibrous tumour In: Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP et al. (eds) WHO Classification of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart 4th edn Volume 7. IARC: Lyon, France, 2015, pp 178–179.

Doyle LA, Vivero M, Fletcher CD et al. Nuclear expression of STAT6 distinguishes solitary fibrous tumor from histologic mimics. Mod Pathol 2014;27:390–395.

Chmielecki J, Crago AM, Rosenberg M et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies a recurrent NAB2-STAT6 fusion in solitary fibrous tumors. Nat Genet 2013;45:131–132.

Mohajeri A, Tayebwa J, Collin A et al. Comprehensive genetic analysis identifies a pathognomonic NAB2/STAT6 fusion gene, nonrandom secondary genomic imbalances, and a characteristic gene expression profile in solitary fibrous tumor. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2013;52:873–886.

Robinson DR, Wu YM, Kalyana-Sundaram S et al. Identification of recurrent NAB2-STAT6 gene fusions in solitary fibrous tumor by integrative sequencing. Nat Genet 2013;45:180–185.

Antonescu CR, Dal Cin P . Promiscuous genes involved in recurrent chromosomal translocations in soft tissue tumours. Pathology 2014;46:105–112.

Ladanyi M, Antonescu CR, Leung DH et al. Impact of SYT-SSX fusion type on the clinical behavior of synovial sarcoma: a multi-institutional retrospective study of 243 patients. Cancer Res 2002;62:135–140.

Sorensen PH, Lynch JC, Qualman SJ et al. PAX3-FKHR and PAX7-FKHR gene fusions are prognostic indicators in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the children's oncology group. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:2672–2679.

Huang HY, Illei PB, Zhao Z et al. Ewing sarcomas with p53 mutation or p16/p14ARF homozygous deletion: a highly lethal subset associated with poor chemoresponse. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:548–558.

Akaike K, Kurisaki-Arakawa A, Hara K et al. Distinct clinicopathological features of NAB2-STAT6 fusion gene variants in solitary fibrous tumor with emphasis on the acquisition of highly malignant potential. Hum Pathol 2015;46:347–356.

Barthelmess S, Geddert H, Boltze C et al. Solitary fibrous tumors/hemangiopericytomas with different variants of the NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion are characterized by specific histomorphology and distinct clinicopathological features. Am J Pathol 2014;184:1209–1218.

Cheah AL, Billings SD, Goldblum JR et al. STAT6 rabbit monoclonal antibody is a robust diagnostic tool for the distinction of solitary fibrous tumour from its mimics. Pathology 2014;46:389–395.

Yoshida A, Tsuta K, Ohno M et al. STAT6 immunohistochemistry is helpful in the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2014;38:552–559.

Doyle LA, Tao D, Marino-Enriquez A . STAT6 is amplified in a subset of dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Mod Pathol 2014;27:1231–1237.

Creytens D, Libbrecht L, Ferdinande L . Nuclear expression of STAT6 in dedifferentiated liposarcomas with a solitary fibrous tumor-like morphology: a diagnostic pitfall. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2015;23:462–463.

Huang HY, Brennan MF, Singer S et al. Distant metastasis in retroperitoneal dedifferentiated liposarcoma is rare and rapidly fatal: a clinicopathological study with emphasis on the low-grade myxofibrosarcoma-like pattern as an early sign of dedifferentiation. Mod Pathol 2005;18:976–984.

Kawai A, Woodruff J, Healey JH et al. SYT-SSX gene fusion as a determinant of morphology and prognosis in synovial sarcoma. N Engl J Med 1998;338:153–160.

Le Deley MC, Delattre O, Schaefer KL et al. Impact of EWS-ETS fusion type on disease progression in Ewing's sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor: prospective results from the cooperative Euro-E.W.I.N.G. 99 trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1982–1988.

Nielsen TO, Poulin NM, Ladanyi M . Synovial sarcoma: recent discoveries as a roadmap to new avenues for therapy. Cancer Discov 2015;5:124–134.

de Alava E, Kawai A, Healey JH et al. EWS-FLI1 fusion transcript structure is an independent determinant of prognosis in Ewing's sarcoma. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:1248–1255.

Mertens F, Antonescu CR, Hohenberger P et al. Translocation-related sarcomas. Semin Oncol 2009;36:312–323.

Wang L, Motoi T, Khanin R et al. Identification of a novel, recurrent HEY1-NCOA2 fusion in mesenchymal chondrosarcoma based on a genome-wide screen of exon-level expression data. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2012;51:127–139.

Guillou L, Benhattar J, Gengler C et al. Translocation-positive low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of a series expanding the morphologic spectrum and suggesting potential relationship to sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma: a study from the French Sarcoma Group. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:1387–1402.

Sugita S, Aoyama T, Kondo K et al. Diagnostic utility of NCOA2 fluorescence in situ hybridization and Stat6 immunohistochemistry staining for soft tissue angiofibroma and morphologically similar fibrovascular tumors. Hum Pathol 2014;45:1588–1596.

Hajdu M, Singer S, Maki RG et al. IGF2 over-expression in solitary fibrous tumours is independent of anatomical location and is related to loss of imprinting. J Pathol 2010;221:300–307.

Bisceglia M, Galliani C, Giannatempo G et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the central nervous system: a 15-year literature survey of 220 cases (August 1996-July 2011). Adv Anat Pathol 2011;18:356–392.

Acknowledgements

We thank Chang Gung genomic core laboratory for technical assistance (CMRPG880251). This work was sponsored by Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology (NSC102-2628-B-182A-002-MY3 to HYH) and Chang Gung Hospital (CMRPG8C0982 to HYH, CMRPG8C1231 to PCL, and CMRPG8Cl241 to SLY).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work was presented in part at the 104th annual meeting of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Boston, USA, March 21–27, 2015

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Modern Pathology website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tai, HC., Chuang, IC., Chen, TC. et al. NAB2–STAT6 fusion types account for clinicopathological variations in solitary fibrous tumors. Mod Pathol 28, 1324–1335 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2015.90

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2015.90

This article is cited by

-

Adenofibromatous Solitary Fibrous Tumor: An Unusual Morphologic Variant Occurring in the Sinonasal Tract

Head and Neck Pathology (2022)

-

Solitary fibrous tumor of the adrenal gland – its biological behavior and report of a new case

Surgical and Experimental Pathology (2021)

-

A case of a large solitary fibrous tumor in the thigh, displaying NAB2ex4-STAT6ex2 gene fusion

Skeletal Radiology (2021)

-

Histological and molecular features of solitary fibrous tumor of the extremities: clinical correlation

Virchows Archiv (2020)

-

What’s new in fibroblastic tumors?

Virchows Archiv (2020)