Abstract

Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinomas harbor chromosome translocations involving the Xp11 breakpoint, resulting in gene fusions involving the TFE3 gene. The most common subtypes are the ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas resulting from t(X;17)(p11;q25) translocation, and the PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas, resulting from t(X;1)(p11;q21) translocation. A formal clinical comparison of these two subtypes of Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinomas has not been performed. We report one new genetically confirmed Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinoma of each type. We also reviewed the literature for all published cases of ASPSCR1-TFE3 and PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas and contacted all corresponding authors to obtain or update the published follow-up information. Study of two new, unpublished cases, and review of the literature revealed that 8/8 patients who presented with distant metastasis had ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas, and all but one of these patients either died of disease or had progressive disease. Regional lymph nodes were involved by metastasis in 24 of the 32 ASPSCR1-TFE3 cases in which nodes were resected, compared with 5 of 14 PRCC-TFE3 cases (P=0.02).; however, 11 of 13 evaluable patients with ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas who presented with N1M0 disease remained disease free. Two PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas recurred late (at 20 and 30 years, respectively). In multivariate analysis, only older age or advanced stage at presentation (not fusion subtype) predicted death. In conclusion, ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas are more likely to present at advanced stage (particularly node-positive disease) than are PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas. Although systemic metastases portend a grim prognosis, regional lymph node involvement does not, at least in short-term follow-up. The tendency for PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas to recur late warrants long-term follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinomas are characterized by chromosome translocations involving the Xp11 breakpoint, resulting in gene fusions involving the TFE3 transcription factor gene, which maps to this locus.1, 2 The most common subtypes of Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinomas are the ASPSCR1-TFE3 (also known as ASPL-TFE3) renal cell carcinomas resulting from a t(X;17)(p11;q25) translocation,3 and the PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas, resulting from a t(X;1)(p11;q21) translocation.4 As most cytogenetically or molecularly confirmed cases have been described in case reports or small series, a formal clinical comparison of these two subtypes of Xp11 translocation RCC has not been performed.

We report two new genetically confirmed Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinomas, one with an ASPSCR1-TFE3 gene fusion and the other with a PRCC-TFE3 gene fusion. We review the literature for all published cases of ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas (41 cases, 20 publications) and PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas (37 cases, 19 publications) and contacted all corresponding authors to obtain or update published follow-up information. We compiled and statistically analyzed the information received by age, gender, stage, treatment, and follow-up.

Materials and methods

The two new, unpublished cases are from the files of the authors. We reviewed the literature for other cases of genetically confirmed PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas and ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas. Cases were considered to be genetically confirmed if they demonstrated on cytogenetics the characteristic chromosome translocations of the PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma [t(X:1)(p11.2;q21)] or ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma [t(X;17)(p11.2;q25)], or demonstrated the characteristic PRCC-TFE3 or ASPSCR1-TFE3 fusion products on reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR). Published cases were found in the literature by Pub Med search using search terms ‘TFE3’ and ‘Xp11’. Forty-one ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas were identified in 20 publications and 37 PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas were identified in 19 publications. Details of these cases, along with the two new cases reported herein, are presented in Tables 1 and 2. We attempted to contact all corresponding authors of the publications to update follow-up information, and add details of therapy which were not included in the original reports of these cases. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, updated follow-up information was obtained for 4 of 36 published PRCC-TFE3 cases, and 16 of 40 previously published ASPSCR1-TFE3 cases. Updated or new follow-up information not presented in the original publication is shown by italics in Tables 1 and 2. Stage was determined using the current 2010 American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system.5Comparisons between the PRCC-TFE3 RCC and ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas were analyzed using the two-tailed Fisher exact test. Multivariate analysis of survival was performed by Cox regression, using age (as a continuous variable), stage, fusion type, and gender. Statistics were performed using STATA3 (College Station, TX, USA).

Immunohistochemical labeling for TFE3 was performed for both of the new cases using 4-μm sections deparaffinized in xylene for 30 min and rehydrated using graded ethanol concentrations. Antigen retrieval was performed using steaming. Immunohistochemical labeling was performed using the avidin–biotin peroxidase complex technique and 3′,3′-diaminobenzidine as the chromogen. We used the P16 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA; steam in EDTA buffer, 1:600), which binds to the C-terminal portion of TFE3 protein downstream of known fusion breakpoints as previously described.6 RT-PCR for the ASPSCR1-TFE3 fusion product was performed as previously described.3

One patient’s clinical course deserves special attention. This is a patient who was previously reported to have developed both an ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma (ASPSCR1-TFE3 Case 6) and a contralateral PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma (PRCC-TFE3 Case 13) in the setting of long-term cyclophosphamide therapy for systemic lupus erythematosis, which led to the realization that Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinomas may be associated with prior exposure to chemotherapy.7 This patient subsequently developed an abdominal recurrence of renal cell carcinoma. As slides from the recurrence are not available and the subtype of this recurrence was not determined, it is impossible for us to determine if this is a recurrence of his ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma or PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma. Therefore, outcome data on this patient is excluded from the current analysis.

Results

PRCC-TFE3 Renal Cell Carcinoma Case Report

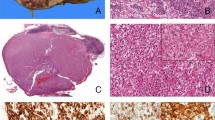

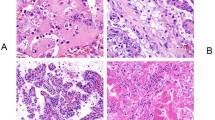

This patient was a 14-year-old boy who suffered trauma while playing soccer and developed uncontrollable abdominal hemorrhage. Intra-operatively, he was found to have a left renal neoplasm, which had ruptured into the peritoneal cavity. The child underwent left nephrectomy, which revealed a 7 cm hemorrhagic mass with a calcified capsule. Microscopically, the neoplasm demonstrated both nested and papillary architectures, and was composed of cells with moderate amounts of clear to faintly eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1). Scattered psammoma bodies were present. Intrarenal vascular invasion was present, but perirenal lymph nodes were not identified for microscopic examination. The neoplasm demonstrated diffuse nuclear immunoreactivity for TFE3. Cytogenetic analysis revealed a t(X;1) (p11.2;q21) translocation, which characteristically results in a PRCC-TFE3 gene fusion.

Five months after surgery, the patient began ironotecan adjuvant therapy, but did not tolerate it and could not complete the treatment course. Two years later, the patient developed metastasis to the left neck (likely representing lymph node metastasis). The patient developed multiple abdominal recurrences over the next 2 years, which were treated by multiple debulking procedures, and received two cycles of ironotecan and vincristine during this time. He received three cycles of sunitinib, which stabilized his condition for approximately 6 months at which time he developed a metastasis to the psoas muscle, which was then debulked. He received carboplatin and paxlitaxel, but developed further metastatic disease. He received gemcitabine, doxorubicin, and oxaliplatin, but progressed on these and died 2 months later, 5.5 years after nephrectomy, at the age of 20 years. His last imaging study revealed masses in the left renal fossa, left paracolic gutter, left psoas muscle, left presacrum, and left pleura.

ASPSCR1-TFE3 Renal Cell Carcinoma Case Report

A 16-year-old white girl presented with a left upper quadrant mass. Computerized tomography revealed a calcified renal mass, with several enlarged perirenal lymph nodes, lytic destruction of the L1 vertebra, and two small lung nodules. A left radical nephrectomy was performed with removal of the left renal hilar lymph nodes as well as a left periaortic lymph node dissection. The upper pole mass measured 15 cm in greatest dimension, and on sectioning had a tan-white, friable appearance with cysts and hemorrhagic areas. Microscopically, the mass had a prominent papillary architecture and areas with solid nest formation (Figure 2). The neoplastic cells had abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and nuclei with prominent central nucleoli. Multiple psammoma bodies were identified, which correlated with the calcifications seen in imaging. Multifocal vascular invasion was seen. A left hilar lymph node and multiple lymph nodes in the left periaortic lymph node dissection were involved by metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

Immunohistochemical studies revealed diffuse nuclear immunoreactivity for TFE3 protein and minimal labeling for S 100 protein. Rare cells were labeled for epithelial membrane antigen, cytokeratin AE1/AE3, and cytokeratin 7. At the submitting institution, reactions for glial fibrillary acidic protein, chromogranin, desmin, and actin were all negative.

Ultrastructural examination revealed moderately preserved cells with swollen mitochondria and membrane-bound lysosomal structures. There was no crystalline-like material present. RT-PCR with ASPSCR1 and TFE3 primers was positive for the type 1 ASPSCR1-TFE3 fusion product. A computed tomography scan performed 1 year later showed progression in the retroperitoneal lymph nodes as well as in the hilum of the left lung. At this point, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Literature Review of PRCC-TFE3 Renal Cell Carcinomas and ASPSCR1-TFE3 Renal Cell Carcinomas

PRCC-TFE3 cases

The new PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma case and results of the literature review are presented in Table 1.4, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 Follow-up for these cases ranged from 1 to 30 years (mean 4.5 years, median 7.1 years). The mean age of these patients was 24 years and the median 20 years (range 2–69 years). The gender distribution of these cases was nearly equal (17 males and 20 females). Among these 37 cases, stage was reported in 26: 9 were stage 1; 2 were stage 2; 13 were stage 3; and 2 were stage 4. Among patients with stage 1 disease, all nine on whom there was follow-up showed no evidence of disease. The one stage 2 patient with follow-up recurred at 2.5 years following resection. Among the seven stage 3 patients on whom there is follow-up, four died of disease. Two developed metastases (retroperitoneum and liver) 2 years after resection, and one patient showed no evidence of disease after 30 months. Two patients presented with stage 4 disease due to locally advanced primary tumors (T4 disease) but follow-up was not available on those patients.

Lymph node status was evaluable in only 14 of the 37 patients; in the remaining cases, lymph nodes were not examined microscopically. Among the patients for whom lymph nodes were examined, nine had uninvolved nodes (N0 disease), whereas five had involved nodes (N1 disease). Four patients in the node-positive group had stage 3 disease (ie, no evidence of distant metastasis or T4 disease). Among these patients, two died of disease at 10 years and 20 months, respectively, whereas one developed retroperitoneal metastases at 2 years. One patient showed no evidence of disease at 36 months follow-up. No patient with PRCC-TFE3 presented with distant metastases (M1 disease).

ASPSCR1-TFE3 cases

The new ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma case and cases from the literature review are presented in Tables 2 and 3.17, 26, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49 Follow-up for these cases ranged from 0.17 to 19 years (median 2.75 years, mean 5.35 years), which on average is less than that for the PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas. The mean age of these patients was 21 years and the median age was 13 years (range 1–75 years). There was a female predominance (25 F: 16M). Stage was evaluable in 40 of the 41 ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas in the literature. Among these cases, 9 presented at stage 1, 1 at stage 2, 18 at stage 3, and 12 at stage 4. Among patients with stage 1 ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma, six showed no evidence of disease in follow-up, whereas three patients died by disease at 26 months, 40 months, and 8.9 years. The solitary patient with stage 2 disease showed no evidence of disease at 8 years. Among the 18 patients with stage 3 ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas, 14 had follow-up. Twelve of these patients showed no evidence of disease including three patients who received no adjuvant therapy and had prolonged follow-up (9 years, 10 years, and 19 years, respectively). Two patients died of disease at 31 months and 23 months, respectively. Among the 12 patients with stage 4 ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma, 4 died of disease, 4 are alive with progressive disease, 2 are alive with disease, and 2 showed no evidence of disease at 4.5 and 11 years follow-up.

Among the 41 cases of ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma, 32 had nodes examined microscopically. Of these, 24 had involved lymph nodes (N1 disease), whereas 8 had uninvolved lymph nodes (N0 disease). Among 16 ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma patients with N1 stage 3 disease (ie, no evidence of distant metastasis or T4 disease which would make them stage 4), 11 showed no evidence of disease, including the 3 patients noted above who had no adjuvant therapy and prolonged follow-up. Two patients died of disease at 31 months and 23 months, respectively, whereas follow-up was not available on three of these cases.

Eight patients with ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma presented with distant metastases (M1 disease). Four of these patients died of disease, whereas three are alive with progressive disease. One patient who presented with a liver metastasis shows no evidence of disease with 4.5 years of follow-up. This patient had received interferon-2 alpha and vaccine tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells.

Comparison of ASPSCR1-TFE3 and PRCC-TFE3 Renal Cell Carcinomas

The data reported above are summarized in Table 3 for comparison. The ages of patients with ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma and PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma were not statistically different. Although the numbers are small, ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas were statistically more likely to present with involved nodes (24 of 32 evaluable cases) than were PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas (5 of 14 evaluable cases (P=0.02). All eight patients from the literature who presented with distant metastases (M1 disease) had ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas. Stated differently, 8 of 40 patients with ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma on whom stage was recorded presented with distant metastasis, whereas none of the 26 such patients with PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma did (P=0.02). However, the patients with N1 stage 3 disease (ie, involved nodes but no evidence of T4 disease or distant metastases) tended to have different outcomes. Although the difference was not statistically significant, three of the four patients with N1 stage 3 PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas either died of disease or progressed, whereas only 2 of 13 evaluable ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas presenting with N1 stage 3 disease progressed (P=0.06).

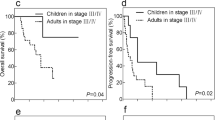

On multivariate analysis, only older age (hazard ratio 1.04, P=0.003) and advanced stage at presentation (stage 4 versus stage 1, 2, and 3; hazard ratio 5.1, P=0.018) independently predicted death. Fusion subtype (P=0.287) and gender (P=0.848) were not independent significant predictors of death. A Kaplan–Meier plot of survival versus stage is presented in Supplementary Figure 1.

Discussion

We report new cases of PRCC-TFE3 and ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma, and review the existing literature on these neoplasms (mostly small series and case reports). We attempted to contact the authors of all reports in the literature to provide the most current update of knowledge on these neoplasms. One striking finding of our study is that there was a tendency for ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas to present at more advanced stage than the PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas. This tendency for advanced stage was reflected in a greater likelihood of having involved regional lymph nodes (N1 disease), as well as a greater likelihood of presenting with distant metastases (M1 disease). In our original reports of these distinctive neoplasms, we noted a trend toward a difference in the tendency to present at advanced stage,3, 4 but review of the literature provides additional cases, which make this difference statistically significant. Furthermore, we note that urologists performing nephrectomies often perform a lymph node dissection only if the lymph nodes seem enlarged by radiography or intraoperative examination. Along these lines, the greater frequency of lymph node sampling among the ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas (32 of 41 cases) compared with the PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas (14 of 37 cases) supports the concept that the former spreads to lymph nodes more frequently.

It is tempting to speculate that the difference in clinical presentation between the ASPSCR1-TFE3 and PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas reflects functional differences between the two fusion proteins, which are postulated to act as transcription factors, which drive the underlying biology of these neoplasms. Along these lines, we previously noted that the ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas tend to have higher nuclear grade and more voluminous cytoplasm than the PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas.3, 4 A further more objective difference between these neoplasms is their differential immunohistochemical expression of the cysteine protease cathepsin K.50, 51 We have previously shown that a majority (12 of 14, or 86%) of PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas diffusely express cathepsin K, whereas all eight ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas tested have been negative for this immunohistochemical marker. As cathepsin K expression is typically driven by the transcription factor MITF, which is in the same family as TFE3 and TFEB, and has overlapping activity, our hypothesis has been that the PRCC–TFE3 fusion protein is better able to activate cathepsin K expression compared with the ASPSCR1–TFE3 fusion protein. It seems plausible that biological distinctions such as this and others between these two neoplasms may drive the differing clinical behavior documented in this report. We caution, however, that the overall numbers of cases in this literature review are still small, and the level of statistical significance of the difference is not robust. Furthermore, we recognize that the cases reviewed here were resected, processed, and treated at different institutions using different protocols, so that differences in surgical approach, pathologic examination, and treatment could potentially have influenced the data. Furthermore, we noted considerable clinical heterogeneity in the cases, with some patients with advanced disease dying rapidly, whereas others followed a more indolent course. Therefore, we believe that further experience and prospective data are required before our observations can be confirmed.

Although the ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas were more likely to present at advanced stage than the PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas, we note that those patients with node positive but non-metastatic (N1 stage 3 disease) tended to have a worse outcome when they had a PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma than if they had an ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma, although the difference was not statistically significant. Moreover, PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas have been documented in the literature to recur late (20 and 30 years after diagnosis). Hence, advanced local stage at presentation may not reflect the overall long-term outcome of these patients. As these neoplasms typically demonstrate low proliferation rates (typically less than 5%)3, 4 and are known to have the capacity to recur late, long-term (over 20 year) follow-up is needed to more accurately determine their biologic behavior. Furthermore, a low proliferative rate may explain the relatively indolent course of ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma in patients 3 and 8 who have each survived with disease for over 10 years

It should be noted that there is a precedent for the association of different fusion subtypes within the same translocation-associated neoplasm with differing biological features and clinical outcomes. For example, among Ewing sarcomas, the type 1 EWS–FLI1 fusion (fusing exon 7 of EWS with exon 6 of FLI1) is associated with lower transcriptional activity, lower proliferative rate, and a more favorable outcome than are other variant EWS–FLI1 gene fusions,52, 53, 54 although current treatment protocols have eliminated this prognostic advantage.55 Among alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas, those tumors with the PAX7–FOXO1 gene fusion have a more favorable outcome than those with the PAX3–FOXO1 gene fusion.56 Further differences include the fact that PAX7–FOXO1 fusion gene is amplified in the majority of alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas, whereas the PAX3–FOXO1 is not.57 Finally, the SYT1–SSX2 gene fusion in synovial sarcoma has been more strongly associated with monophasic spindle cell histology compared with the SYT1–SSX1 gene fusion,58 although whether fusion status is an independent predictor of outcome is debated.59, 60 Although these examples highlight the potential for fusion subtype to impact patient care, they emphasize the need for prospective data to validate these distinctions. Regardless, as Barr et al have pointed out,61 fusion subtype has relevance in detection of minimal residual disease, in design of potential antisense-targeted therapy, and in distinction of second primaries from recurrences, regardless of any prognostic implications.

The reported cases have raised the possibility that older age is an unfavorable prognostic factor for Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinomas.29, 33, 46 This was confirmed in our multivariate analysis, in that older age and advanced stage independently predicted death. The association of older age with worse outcome is supported by recent genetic data by Malouf et al,62 who found more genetic alterations (particularly chromosome 17q gain) in adult Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinomas compared with pediatric cases. Although the ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas tended to present at advanced stage, advanced stage (specifically stage 4 disease) but not fusion type independently predicted death. This likely reflects the relatively indolent course of patients with stage 3 N1M0 ASPSCR1-TFE3 renal cell carcinomas, which counterbalances the aggressive course of ASPSCR1-TFE3 patients with stage 4 disease. We caution, however, that the number of cases in our series is small, and it is possible that node status impacts long-term outcome. We recognize that the limited power of our study because of the small number of cases does not allow one to definitely conclude that node status is not important.

Finally, review of the literature on these renal cell carcinomas as well as that of other genetically confirmed Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinomas provides some useful information for clinicians who must treat patients with this disease. We note that one of the patients in this series (ASPSCR1-TFE3-case 40) responded to sorafenib, and that the new PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma case reported in this study stabilized under sunitinib therapy. Moreover, two other genetically confirmed Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinomas in the literature (fusion partner not determined) responded to sunitinib.63, 64 These data suggest the possible efficacy of utilizing tyrosine kinase inhibitors in treating these neoplasms. The Juvenile Renal Cell Carcinoma network has reported a partial response and disease stabilization in patients receiving mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor therapy, although it is not clear how many of these cases were confirmed to be Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinomas genetically.65 However, we note that other patients in our review failed to respond to these same treatments. Moreover, the one patient who has survived with no evidence of disease despite hematogenous metastasis (M1 disease; ASPSCR1-TFE3 Case 33) responded to immune therapy including tumor vaccine and interleukin 2 treatments, whereas these treatments have been ineffective in other patients (such as case 12 of reference 38 and case 2 of reference 26). These reports highlight that a single effective treatment remains out of reach at the current time for these neoplasms, and underscore the importance of further genetic analysis66, 67 to identify potential targets such as MET (known to be induced by TFE3 gene fusions66) for effective, nontoxic therapies for these patients.

References

Ross H, Argani P . Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinoma. Pathology 2010;42:369–373.

Argani P, Ladanyi M . Renal carcinomas associated with Xp11.2 translocations/TFE3 gene fusions In: Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn IA (eds). World Health Organization Classification of Tumors: Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. IARC Press: Lyon, 2004, pp 37–38.

Argani P, Antonesu CR, Illei PB et al. Primary renal neoplasms with the ASPL-TFE3 gene fusion of alveolar soft part sarcoma: a distinctive tumor entity previously included among renal cell carcinomas of children and adolescents. Am J Pathol 2001;159:179–192.

Argani P, Antonescu CR, Couturier J et al. PRCC-TFE3 renal carcinomas: morphologic, immunohistochemical, ultrastructural, and molecular analysis of an entity associated with the t(X;1)(p11.2;q21). Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:1553–1566.

American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). Cancer Staging Handbook from the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual 7th edn Springer: New York, NY, 2010.

Argani P, Lal P, Hutchinson B et al. Aberrant nuclear immunoreactivity for TFE3 in neoplasms with TFE3 gene fusions: a sensitive and specific immunohistochemical assay. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:750–761.

Argani P, Lae M, Ballard ET et al. Translocation carcinomas of the kidney after chemotherapy in childhood. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:1529–1534.

Tonk V, Wilson KS, Timmons CF et al. Renal cell carcinoma with translocation (X;1). Further evidence for a cytogenetically defined subtype. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1995;81:72–75.

Dal Cin P, Stas M, Sciot R et al. Translocation (X;1) reveals metastasis 31 years after renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1998;101:58–61.

Perot C, Bougaran J, Boccon-Gibod L et al. Two new cases of papillary renal cell carcinoma with t(X;1)(p11;q21) in females. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1999;110:54–56.

Yenamandra A, Zhou X, Trinchitella L et al. Renal cell carcinoma with X;1 translocation in a child with Klinefelter syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1998;77:281–284.

Desangles F, Camparo P, Fouet C et al. Translocation (X;1) associated with a nonpapillary carcinoma in a young woman: a new definition for an Xp11.2 RCC subtype. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1999;113:141–144.

Zattara-Cannoni H, Daniel L, Roll P et al. Molecular cytogenetics of t(X;1)(p11.2;q21) with complex rearrangements in a renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2000;123:61–64.

Perot C, Boccon-Gibod L, Bouvier R et al. Five new cases of juvenile renal cell carcinoma with translocations involving Xp11.2: a cytogenetic and morphologic study. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2003;143:93–99.

Onder AM, Teomete U, Argani P et al. PRCC-TFE3 renal cell carcinoma in a boy with a history of contralateral mesoblastic nephroma. Pediatr Nephrol 2006;21:1471–1475.

Sidhar S, Clark J, Gill S et al. The t(X;1)(p11.2q21.2) translocation in papillary renal cell carcinoma fuses a novel gene PRCC to the TFE3 transcription factor gene. Hum Mol Genet 1996;5:1333–1338.

Camparo P, Vasiliu V, Molinié V et al. Renal translocation carcinomas, clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and gene expression profiling analysis of 31 cases with a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:656–670.

Altinok G, Kattar MM, Mohamed A et al. Pediatric renal carcinoma associated with Xp11.2 translocations/TFE3 gene fusions and clinicopathologic associations. Pediatr Devel Pathol 2005;8:168–180.

Sangkhathat S, Kusafuka T, Yoneda A et al. Renal cell carcinoma in a pediatric patient with an inherited mitochondrial mutation. Pediatr Surg Int 2005;21:745–747.

Meloni AM, Bridge J, Sandberg AA . Reviews on chromosome studies in urological tumors. J Urol 1992;148:253–265.

Meloni AM, Dobbs RM, Pontes JE et al. Translocation (X;1) in papillary renal cell carcinoma. A new cytogenetic subtype. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1993;54:1–6.

Shipley JM, Birdsall S, Clark J et al. Mapping the X chromosome breakpoint in two papillary renal cell carcinoma cell lines with a t(X;1)(p11.2;q21.2) and the first report of a female case. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1995;71:280–284.

De Jong B, Molenaar IM, Leeuw JA et al. Cytogenetics of a renal adenocarcinoma in a 2-year-old child. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1986;15:165–169.

Kardas I, Denis A, Babinska M et al. Translocation (X;1)(p11.2;q21) in a papillary renal cell carcinoma in a 14-year-old girl. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1998;101:159–161.

Dijkhuizen T, van den Berg E, Störkel S et al. Distinct features for chromophilic renal cell cancer with Xp11.2 breakpoints. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1998;104:75–76.

Komai Y, Fujiwara M, Fujii Y et al. Adult Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinoma diagnosed by cytogenetics and immunohistochemistry. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:1170–1176.

Hung CC, Pan CC, Lin CC et al. Xp11.2 translocation renal cell carcinoma: clinical experience of Taipei Veterans General Hospital. J Chin Med Assoc 2011;74:500–504.

Macher-Geoppinger S, Roth W, Wagener N et al. Molecular heterogeneity of TFE3 activation in renal cell carcinomas. Mod Pathol 2012;25:308–315.

Pan CC, Sung M-T, Huang H-Y et al. High chromosomal copy number alterations in Xp11 tranlocation renal cell carcinomas detected by comparative genomic hybridization are associated with aggressive behavior. Am J Surg Pathol 2013;37:1116–1119.

Tomlinson GE, Nisen PD, Timmons CF et al. Cytogenetics of a renal cell carcinoma in a 17-month-old child. Evidence for Xp11.2 as a recurring breakpoint. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1991;57:11–17.

Renshaw AA, Granter SR, Fletcher JA et al. Renal cell carcinomas in children and young adults: increased incidence of papillary architecture and unique subtypes. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:795–802.

Zambrano E, Reyes-Mugica M . Renal cell carcinoma with t(X;17): singular pediatric neoplasm with specific phenotype/genotype features. Pediatr Devel Pathol 2002;6:84087.

Argani P, Olgac S, Tickoo SK et al. Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinoma in adults: expanded clinical, pathologic, and genetic spectrum. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:1159–1160.

Huang FS, Zwerdling T, Stern LE et al. Renal cell carcinoma as a secondary malignancy after treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2001;23:609–611.

Heimann P, El Housni H, Ogur G et al. Fusion of a novel gene, RCC17 to the TFE3 gene in t(X:17)(p11.2;q25.3) bearing papillary renal cell carcinomas. Cancer Res 2001;15:4130–4135.

Geller JI, Argani P, Adeniran A et al. Translocation renal cell carcinoma: lack of negative impact due to lymph node spread. Cancer 2008;112:1607–1616.

Chen C, Hsueh C, Lai JY et al. Renal cell carcinoma with t(X;17)(p11.2;q25) in a 6 year old Taiwanese boy. Virchows Arch 2007;450:215–219.

Ramphal R, Pappo A, Zielenska M et al. Clinical, pathologic, and molecular abnormalities associated with the members of the MiT transcription factor family. Am J Clin Pathol 2006;126:349–364.

Hernandez-Marti et al. Renal adenocarcinoma in an 8-year-old child with a t(X;17)(p11.2;q25). Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1995;83:82–83.

Caracao M et al. Renal cell carcinoma in children: a different disorder from its adult counterpart? Med Pediatr Oncol 1998;31:153–158.

Barroca H . Cytologic and cytogenetic diagnosis of pediatric renal cell carcinoma associated with t(X;17). Acta Cytol 2008;52:384–386.

Kuroda N et al. Diagnostic pitfall on the histological spectrum of adult-onset renal carcinoma associated with Xp11.2 translocations/TFE3 gene fusions. Med Mol Morphol 2010;43:86–90.

Rakheja D, Kapur P, Tomlinson GE et al. Pediatric renal cell carcinomas with Xp11.2 rearrangements are immunoreactive for hMLH1 and hMSH2 proteins. Pediatr Devel Pathol 2005;8:615–620.

Zhong M, De Angelo P, Osborne L et al. Dual-color, break-apart FISH assay on paraffin-embedded tissues as an adjunct to diagnosis of Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinoma and alveolar soft part sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:757–766.

Klatte T, Streubel B, Wrba F et al. Renal cell carcinoma associated with transcription factor E3 expression and Xp11.2 translocation: incidence, characteristics, and prognosis. Am J Clin Pathol 2012;137:761–768.

Sukov WR, Hodge JC, Lohse CM et al. TFE3 rearrangements in adult renal cell carcinoma: clinical and pathologic features with outcome in a large series of consecutively treated patients. Am J Surg Pathol 2012;36:663–670.

Gaillot-Durand L, Chevallier M, Colombel M et al. Diagnosis of Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinomas in adult patients under 50 years: interest and pitfalls of automated immunohistochemical detection of TFE3 protein. Pathol Res Pract 2013;15:83–89.

Mir MC, Trilla E, de Torres IM et al. Altered transcription factor E3 expression in unclassified adult renal cell carcinoma indicates adverse pathological features and poor outcome. BJU Int 2011;108:E71–E76.

Hou M-M, Hsieh J-J, Chang N-J et al. Response to Sorafenib in a patient with metastatic Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinoma. Clin Drug Investig 2010;30:799–80.

Martignoni G, Pea M, Gobbo S et al. Cathepsin-K immunoreactivity distinguishes MiTF/TFE family renal translocation carcinomas from other renal carcinomas. Mod Pathol 2009;22:1016–1022.

Martignoni G, Gobbo S, Camparo P et al. Differential expression of cathepsin-K in neoplasms harbouring TFE3 gene fusions. Mod Pathol 2011;24:1313–1319.

Lin PP, Brody RI, Hamelin AC et al. Differential transactivation by alternative EWS-FLI1 fusion proteins correlates with clinical heterogeneity in Ewing's sarcoma. Cancer Res 1999;59:1428–1432.

de Alava E, Panizo A, Antonescu CR et al. Association of EWS-FLI1 type 1 fusion with lower proliferative rate in Ewing's sarcoma. Am J Pathol 2000;156:849–855.

de Alava E, Kawai A, Healey JH et al. EWS-FLI 1 fusion transcript structure is an independent determinant of prognosis in Ewing’s sarcoma. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:1248–1255.

van Doorninck JA, Ji L, Schaub B et al. Current treatment protocols have eliminated the prognostic advantage of type 1 fusions in Ewing sarcoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1989–1994.

Skapek SX, Anderson J, Barr FG et al. PAX-FOXO1 fusion status drives unfavorable outcome for children with rhabdomyosarcoma: a children's oncology group report. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:1411–1417.

Duan F, Smith LM, Gustafson DM et al. Genomic and clinical analysis of fusion gene amplification in rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2012;51:662–674.

Antonescu CR, Kawai A, Leung DH et al. Strong association of SYT-SSX fusion type and morphologic epithelial differentiation in synovial sarcoma. Diagn Mol Pathol 2000;9:1–8.

Ladanyi M, Antonescu CR, Leung DH et al. Impact of SYT-SSX fusion type on the clinical behavior of synovial sarcoma: a multi-institutional retrospective study of 243 patients. Cancer Res 2002;62:135–140.

Guillou L, Benhattar J, Bonichon F et al. Histologic grade, but not SYT-SSX fusion type, is an important prognostic factor in patients with synovial sarcoma: a multicenter, retrospective analysis. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:4040–4050.

Barr FG, Meyer WH . Role of fusion subtype in Ewing sarcoma. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1973–1974.

Malouf GG, Monzon FA, Couturier J et al. Genomic heterogeneity of translocation renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:4673–4684.

Numakura K, Tsuchiya N, Yuasa T et al. A case study of metastatic Xp11.2 translocation renal cell carcinoma effectively treated with sunitinib. Int J Clin Oncol 2011;16:577–580.

Choueiri TK, Mosquera JM, Hirsch MS . A case of adult metastatic Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinoma treated successfully with sunitinib. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2009;7:E93–E94.

Malouf GG, Camparo P, Oudard S et al. Targeted agents in metastatic Xp11 translocation/TFE3 gene fusion renal cell carcinoma (RCC): a report from the Juvenile RCC Network. Ann Oncol 2010;21:1834–1838.

Tsuda M, Davis IJ, Argani P et al. TFE3 fusions activate MET signaling by transcriptional up-regulation, defining another class of tumors as candidates for therapeutic MET inhibition. Cancer Res 2007;67:919–929.

Kobos R, Nagai M, Tsuda M et al. Combining integrated genomics and functional genomics to dissect the biology of a cancer-associated, aberrant transcription factor, the ASPSCR1-TFE3 fusion oncoprotein. J Pathol 2013;229:743–754.

Acknowledgements

We thank and acknowledge the following colleagues for contributing the updated information on the patients studied: Charles Timmons (Dallas, TX), Raf Sciot (Leuven, Belgium), Liliane Boccon-Gibod (Paris, France), Steven Hajdu (Manhasset, New York), Michael Hughson (Jackson, MS), Jean-Christophe Fournet (Montreal, Quebec), Daryl Lundgrin (Chattanooga, TN), Maria Rodriguez (Miami, FL), Phillipe Camparo (Paris, France), Janet Poulik (Detroit, MI), Yoshinobu Komai and Yasuhisa Fujii (Tokyo, Japan), Robert Newbury (San Diego, CA), Kathryn Ruble (Baltimore, MD), Antonio Perez-Atayde (Boston, MA), A Julian Garvin (Winston-Salem, NC), Joseph McNamara (New Haven, CT), Brad Warner (St Louis, MO), Bo Ngan (Toronto, Canada), Maria João Gil da Costa and Nuno Jorge dos Reis Farinha (Porto, Portugal), Miguel Reyes-Múgica (Pittsburgh,PA), Richard Hessler, Deborah Gourley and Manoo Bhakta (Chattanooga, TN), and Antonio Perez-Atayde (Boston, MA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Modern Pathology website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ellis, C., Eble, J., Subhawong, A. et al. Clinical heterogeneity of Xp11 translocation renal cell carcinoma: impact of fusion subtype, age, and stage. Mod Pathol 27, 875–886 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.208

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.208

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Start of a New Era: Management of Non-Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma in 2022

Current Oncology Reports (2022)

-

Characterization of a distinct low-grade oncocytic renal tumor (CD117-negative and cytokeratin 7-positive) based on a tertiary oncology center experience: the new evidence from China

Virchows Archiv (2021)

-

Renal cell carcinoma with leiomyomatous stroma in tuberous sclerosis complex: a distinct entity

Virchows Archiv (2021)

-

TRIM63 is a sensitive and specific biomarker for MiT family aberration-associated renal cell carcinoma

Modern Pathology (2021)

-

Integrated exome and RNA sequencing of TFE3-translocation renal cell carcinoma

Nature Communications (2021)