Abstract

Molecular pathology is becoming more and more important in present day pathology. A major challenge for any molecular test is its ability to reliably detect mutations in samples consisting of mixtures of tumor cells and normal cells, especially when the tumor content is low. The minimum percentage of tumor cells required to detect genetic abnormalities is a major variable. Information on tumor cell percentage is essential for a correct interpretation of the result. In daily practice, the percentage of tumor cells is estimated by pathologists on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slides, the reliability of which has been questioned. This study aimed to determine the reliability of estimated tumor cell percentages in tissue samples by pathologists. On 47 H&E-stained slides of lung tumors a tumor area was marked. The percentage of tumor cells within this area was estimated independently by nine pathologists, using categories of 0–5%, 6–10%, 11–20%, 21–30%, and so on, until 91–100%. As gold standard, the percentage of tumor cells was counted manually. On average, the range between the lowest and the highest estimate per sample was 6.3 categories. In 33% of estimates, the deviation from the gold standard was at least three categories. The mean absolute deviation was 2.0 categories (range between observers 1.5–3.1 categories). There was a significant difference between the observers (P<0.001). If 20% of tumor cells were considered the lower limit to detect a mutation, samples with an insufficient tumor cell percentage (<20%) would have been estimated to contain enough tumor cells in 27/72 (38%) observations, possibly causing false negative results. In conclusion, estimates of tumor cell percentages on H&E-stained slides are not accurate, which could result in misinterpretation of test results. Reliability could possibly be improved by using a training set with feedback.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Because of the increasing possibilities of targeted therapies and personalized medicine, molecular pathology is becoming more and more important and growing numbers of tests detecting specific gene mutations or other genetic abnormalities are being developed. In the case of pulmonary oncology, for example, the majority of adenocarcinomas harboring activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene show a good response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors like gefitinib and erlotinib.1, 2, 3 The clinical importance of these relatively new drugs is reflected by the number of diagnostic tests that have been developed to detect these mutations.4

A major challenge for any molecular test is its ability to reliably detect mutations in samples consisting of a mixture of tumor cells and normal cells, especially when the tumor content is very low. Each molecular test has its own diagnostic sensitivity: the minimal percentage of mutant alleles present in the sample for the mutation to be detected by the test. The minimally required percentage of tumor cells varies widely, from as little as 0.1% tumor cells for smart amplification process under isothermal conditions and 1% tumor cells for amplification refractory mutation system, to 25% tumor cells for direct sequencing.4 In order to interpret the test results correctly, one has to know whether the percentage of tumor DNA in the sample is sufficient for the specific test used. The percentage of tumor cells is generally estimated by a pathologist, but to the best of our knowledge data concerning the reliability of these estimates have never been published. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the reliability of this estimation.

Materials and methods

Tissue Samples

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slides of 24 transbronchial and transthoracic lung biopsies and 23 lung resection specimens, all containing primary lung carcinomas, were collected from the archives of the Department of Pathology of the University Medical Center, Utrecht, The Netherlands. Slides containing only questionably malignant cells were excluded. For each slide a specific scoring area, containing as little crushing artifacts and necrosis as possible, was delineated. Specific approval of the ethics committee was not necessary for this study, as existing tissue slides were used anonymously.

Tumor Cell Count

To determine the exact percentage of tumor cells in the slides, a Leica Q550MW Imaging Workstation (Leica Microsystems Imaging Solutions Ltd, Cambridge, UK), in combination with a Leica DM LB microscope, a JVC TK-C1480BE Digital Color Video Camera (JVC, Yokohama, Japan), and Leica QProdit software (version 3.2) were used. This setup has the option of demarcating a scoring area on the slide, in which the software selects random high power fields (HPFs). The central areas of these HPFs were used for visually counting tumor and non-tumor cells. These cells were marked manually and counted using the software.

As the cell density of the slides showed a large variation, the number of HPFs to be counted was not fixed. For the biopsy slides, counting was continued until a total of at least 500 cells was reached, for the resection specimens this was at least 1000 cells.

Tumor Cell Estimate

The percentage of tumor cells relative to other cells (eg, stromal cells, inflammatory infiltrate and pre-existing epithelial cells) was independently estimated by nine pathologists. This group consisted of academic pathologists (University Medical Center, Utrecht, The Netherlands) and pathologists from a large referral hospital (St Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, The Netherlands). The estimates were scored in categories of 0–5%, 6–10%, 11–20%, 21–30%, 31–40%, 41–50%, 51–60%, 61–70%, 71–80%, 81–90%, and 91–100% tumor cells.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS software (version 20). For each estimate of a tumor cell percentage by a pathologist, the deviation was calculated as the difference (in number of categories) between the estimated and the counted tumor cell percentage. Mixed models were used to detect differences between pathologists and to investigate the relationship between counted tumor cell percentage and deviation. In these analyses the individual slides were used as subjects, the deviation as the independent variable, the observers as the explanatory variable, and the counted tumor cell percentage as a covariance parameter. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

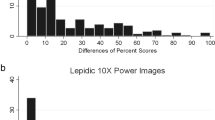

The distribution of the slides over the different categories of tumor content is shown in Table 1. Figure 1 shows representative examples of H&E-stained slides with the corresponding counted percentage of tumor cells and the individual estimates shown in Figure 2. Figure 3 shows the frequency distribution of the deviations from the counted tumor cell percentage of the 423 observations. The data were normally distributed with a mean deviation of 0.144, a median of 0, and a standard deviation of 2.508. The mean range between the lowest and the highest estimate per slide was 6.26 categories. The estimate was correct in 58 (14%) observations. The percentage of tumor cells was underestimated in 176 (42%) observations and overestimated in 189 (45%) observations. A deviation of at least three categories was present in 141 (33%) observations (Table 2). Table 3 shows the results for each observer. The mean deviation was >2 categories for three observers, with a negative mean deviation for two observers and a positive mean deviation for one observer. Figure 4 illustrates the performance of the observers with the largest systematic errors (underestimation for observers two and three, overestimation for observers six and seven) in the resection specimens. The mixed models analysis demonstrated a significant difference between the observers (P<0.001) and a significant influence of the tumor cell percentage in the slide on the observed deviation (P=0.003, regression coefficient −0.2287, ie, overestimation in samples with low tumor content and underestimation in samples with high tumor content). If deviations of 20% between observers were accepted, the mixed models analysis still showed a significant difference between the observers (P<0.001).

Individual estimates per slide, corresponding to the slides shown in Figure 1 (a, c, e, respectively). Arrows in the graphs (a–c) represent the counted percentages of tumor cells.

Frequency distribution of the deviation (number of categories, see Table 1) from the counted gold standard for nine pathologists estimating tumor cell fraction in lung cancer biopsies and resections.

Performance of the observers with the largest systematic errors, compared with the counted percentage of tumor cells, in the resection specimens. The results of two observers with systematic overestimation and of two observers with systematic underestimation are shown. The specimens were ordered according to the ascending percentage of tumor cells.

Samples with Low (<20%) Tumor Cell Content

As a reliable estimate of the tumor cell percentage is especially important in tissue samples with tumor cell percentages around the diagnostic threshold of the molecular test, we focused on the eight slides containing <20% of tumor cells (close to the percentage of tumor cells required for direct sequencing4, 5). Twenty-seven of the 72 (38%) estimates on these slides were >20% tumor cells. Of these 27 overestimates, 26 were made by six observers, whereas only one of the three remaining observers overestimated one of these cases (Table 4). The observers who systematically overestimated the tumor cell percentage were also responsible for the majority of overestimations in the slides containing <20% tumor cells.

Samples with High (>20%) Tumor Cell Content

The remaining 39 slides contained >20% tumor cells. Of the total of 351 estimates on these slides, 61 (17%) were <20% tumor cells. Fifty-six of these underestimates were made by four observers, whereas the five remaining observers underestimated only one case each (Table 4). The observers who systematically underestimated the tumor cell percentage were responsible for the majority of underestimations.

Discussion

The presence of sufficient tumor DNA is crucial for the correct interpretation of a molecular test result of the examined sample. When the proportion of tumor DNA is insufficient, genetic abnormalities can be missed by the test because the signal of the aberrant DNA from the tumor cells can be overshadowed by an excess of normal DNA from non-tumor cells. The treating physician must be aware of this, and the pathology report or molecular test report should contain a disclaimer when the tumor content is around or below the diagnostic threshold of a test. As far as we know, the tumor content of a sample is generally estimated by a pathologist on the H&E-stained slide, the accuracy of which has never been published.

In the present study, we examined the accuracy of tumor cell percentage estimates by comparing these estimates to tumor cell percentages as determined digitally using a video overlay system. The mean deviation was small (only 0.14 categories), but this can be misleading, as it can be the result of large positive and negative deviations that balance each other out. In fact, in about one-third of the observations, there was a deviation of at least three categories and overall there was a wide mean range of 6.26 categories between the lowest and the highest estimate per slide. The small mean deviation does not adequately reflect this inaccuracy and indeed the negative deviations largely compensate for the positive deviations. This improves the mean deviation, but is of no use for the individual estimate. A better way to evaluate the quality of the estimates is therefore the mean absolute deviation, which had an overall magnitude of 2.04 categories. This large inaccuracy of the estimates could have serious consequences for the treatment of patients, as argued below.

We chose a cutoff point of 20% tumor cells, which is close to the reported diagnostic threshold for direct sequencing,4, 5 a widely used technique to detect mutations, to evaluate the clinical consequences of the estimates. Tissue slides containing <20% tumor cells were estimated to contain >20% tumor cells in over one-third (38%) of observations. In case of a molecular test requiring at least 20% tumor cell content, such samples could not only generate false negative test results, but the overestimation of tumor cell content may also lead to unjustified security about the result. This observation is of great clinical importance. In this manner, beneficial therapies could erroneously be withheld from patients. The reverse error can also be the case (sufficient tumor cells present in the sample, but estimated to be below the threshold value of the test), which we observed in 61 out of 351 (17%) estimates. The clinical relevance of this, however, is somewhat smaller, as it can only lead to an unjustified insecurity about the test result, but not to a false result in itself.

In the case of oncogenic point mutations, usually only one of the two copies of a gene is mutated, resulting in only 25% mutated DNA in a sample containing 50% tumor cells. This further increases the need for a sufficient fraction of tumor cells, especially with the use of relatively insensitive detection methods like Sanger sequencing. Genetic abnormalities like aneuploidy, loss of heterozygosity, or amplification of the mutated allele can alter the percentage of mutated DNA, thus making it impossible to calculate this percentage with certainty, even when the percentage of tumor cells is accurately estimated.

The implementation of next generation/massive parallel sequencing creates new opportunities for mutation analysis, as these techniques can detect mutations that are present in a very small fraction of cells in the sample. On the one hand, this reduces the need for an accurate estimation of tumor cell percentage, as the diagnostic threshold of the test is easily met. On the other hand, as these techniques can provide rather precise estimates of the ratio of mutated and non-mutated DNA, information concerning tumor cell percentage is still important in the interpretation of this ratio, for example, to answer questions concerning intratumoral genetic heterogeneity and genetic abnormalities like those mentioned in the previous paragraph.

The main question is how to improve the estimation skills of pathologists. A first possibility would be to emphasize the fact that the observers should make the estimate based on the number of nuclei and not on the fraction of surface area of the tumor tissue present in the slide because generally the tumor cells tend to be larger than the inflammatory or stromal cells. At first glance a tissue section can consist almost completely of tumor tissue, while at second glance small lymphocytes can outnumber the larger tumor cells, thus diluting the tumor DNA enormously and causing only a relatively small fraction of mutated DNA to be present in the DNA sample. Pathologists should also be aware of this when designating areas of tumor for manual microdissection to isolate DNA. Another option could be the use of immunohistochemical stains to clarify which cells are tumor cells and non-tumor cells. This option, however, has the risk of causing overestimation of the fraction of positively stained cells compared with the non-stained cells, as intensely stained cells or nuclei tend to stand out more. Finally, the fraction of tumor cells may be actually counted using methods like the one of the current study to set the gold standard, but this is relatively time consuming.

Erroneous estimates can be produced either by systematic errors (general tendency to over- or underestimate) or by random errors. Both mechanisms seem to have a role in this study, as both the mean deviation and the standard deviation vary considerably between the observers. Three observers showed large systematic errors of at least two categories (systematic underestimation for two observers and overestimation for one observer), whereas others showed large standard deviations of the estimates. A large mean absolute deviation per observer (of at least two categories for four observers) can be the result of a large systematic error, a large random error, or both. Information concerning the type of error made by an individual pathologist could help to improve the estimates of this specific pathologist.

In most pathology laboratories, there never is any feedback on the estimates made, which implies that pathologists who systematically overestimate or underestimate the percentage of tumor cells will not improve their estimates over time. It could be useful to have a training set of slides with a known (counted) percentage of tumor cells. Pathologists could estimate the tumor cell percentage and receive feedback afterwards. Further, such a set of slides could be used as a reference set to review occasionally. Whether any of these options could improve the quality of estimates of tumor cell percentage would be an interesting subject for future research, and we are exploring the possibility of designing a digital training set. In any case, it seems useful to limit the estimation of tumor cell fraction to a few dedicated and trained pathologists per laboratory.

In conclusion, the quality of tumor cell percentage estimates on H&E-stained slides for molecular testing, the manner in which this is performed by pathologists in current practice, is far from optimal, possibly leading to misinterpretation of the test results. Options for improvement include more detailed instructions for the observers or specific training with feedback.

References

Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science 2004;304:1497–1500.

Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2129–2139.

Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M et al. EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from "never smokers" and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:13306–13311.

Thunnissen E, Kerr KM, Herth FJ et al. The challenge of NSCLC diagnosis and predictive analysis on small samples. Practical approach of a working group. Lung Cancer 2012;76:1–18.

Park S, Holmes-Tisch AJ, Cho EY et al. Discordance of molecular biomarkers associated with epidermal growth factor receptor pathway between primary tumors and lymph node metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:809–815.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Oncology Center of the St Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, The Netherlands. The authors would like to thank E Tromp and JC Kelder, St Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, for advice on statistical analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smits, A., Kummer, J., de Bruin, P. et al. The estimation of tumor cell percentage for molecular testing by pathologists is not accurate. Mod Pathol 27, 168–174 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.134

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.134

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

PUREE: accurate pan-cancer tumor purity estimation from gene expression data

Communications Biology (2023)

-

Variant allelic frequency of driver mutations predicts success of genomic DNA methylation classification in central nervous system tumors

Acta Neuropathologica (2023)

-

Deriving tumor purity from cancer next generation sequencing data: applications for quantitative ERBB2 (HER2) copy number analysis and germline inference of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations

Modern Pathology (2022)

-

Biological data annotation via a human-augmenting AI-based labeling system

npj Digital Medicine (2021)

-

The histopathologist is essential in molecular pathology quality assurance for solid tumours

Virchows Archiv (2021)