Abstract

B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma, is a diagnostic provisional category in the World Health Organization (WHO) 2008 classification of lymphomas. This category was designed as a measure to accommodate borderline cases that cannot be reliably classified into a single distinct disease entity after all available morphological, immunophenotypical and molecular studies have been performed. Typically, these cases share features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma, or include characteristics of both lymphomas. The rarity of such cases poses a tremendous challenge to both pathologists and oncologists because its differential diagnosis has direct implications for management strategies. In this study, we present 10 cases of B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma and have organized the criteria described by the WHO into four patterns along with detailed clinical, morphological and immunophenotypic characterization and outcome data. Our findings show a male preponderance, median age of 37 years and a mediastinal presentation in 80% of cases. All cases expressed at least two markers associated with B-cell lineage and good response to combination chemotherapy currently employed for non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The term ‘gray zone lymphoma’ has been used to define a group of aggressive B-cell lymphomas that do not reliably fit into a specific diagnostic category. They represent a continuum between two or more well-characterized clinicopathological entities and show an overlap of morphological, immunophenotypic and molecular features that are traditionally used to separate Hodgkin lymphoma from non-Hodgkin, large B-cell lymphomas.1, 2, 3 The two recognized members of ‘gray zone lymphoma’ include those that show features intermediate between primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma.3, 4, 5, 6, 7

The overlap between primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma has been recognized for some time under the terms ‘mediastinal gray zone lymphoma’,3, 5 or ‘large B-cell lymphoma with Hodgkin-like features’.8 More recently, gene expression profiling studies have demonstrated that the overlap in the expression of genes shared between primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma is significantly higher than that between primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.9, 10, 11, 12 While these findings substantiate the previously described overlap in pathological features between primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma, they also indicate that the relatedness at the molecular level may not always be appreciable at the protein level.13 These findings underscore the heterogeneity of this spectrum of lymphomas and the complexity in defining the criteria for diagnosis and classification. In acknowledgment of this recognized degree of acceptable uncertainty, the current World Health Organization (WHO) classification has introduced a borderline category termed B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma.2, 3, 14, 15 This category is designed to accommodate rare cases that show significant overlap or discordance between the morphology and the immunophenotype of primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma, with transitional features, taking into consideration the acceptable variation in morphology and immunophenotype that is typically exhibited by primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma. As stated in the WHO 2008 classification, we also considered in our study sequential and composite cases of both synchronous and metachronous types.

There are very few publications addressing the clinicopathological characteristics of B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with intermediate features between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Most published reports pre-date the WHO 2008 classification.7 The European Association for Hematopathology (EAHP) 2008 workshop report provides a series of cases classified according to the WHO 2008 classification; however, it does not provide sufficient clinical information, including clinical outcome data.7 Two recent studies have reported clinical outcome information in cases occurring in the pediatric age group.16, 17 Given the rarity of such cases and the difficulty they impose on diagnosis and classification as well as management of patients, additional studies are needed to fully understand the spectrum represented by this new WHO category of lymphomas. In this study, we present the clinicopathological features and outcome of a series of 10 cases of B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with intermediate features between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma.

Materials and methods

Clinical Data

The present series includes 10 cases with the diagnosis of B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with intermediate features between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma, as defined by the WHO 2008 classification.3 All cases were retrieved from the archives of Consultoria em Patologia, a large anatomical pathology reference laboratory, located in Botucatu, São Paulo, Brazil, during the period of January 2008 to December 2010. Clinical information, such as presentation at diagnosis (mediastinal or non-mediastinal), staging according to the modified Ann Arbor criteria, treatment and clinical follow-up, were obtained directly from the treating physicians. Patients were treated according to the following protocols: CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone, CHOP with rituximab (RCHOP) and ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vincristine and decarbazine).

Pathology Findings

In all cases, whole tissue sections from the diagnostic biopsy material obtained before the initiation of treatment were reviewed by three pathologists (GG, YN, CEB) (http://www.conspat.com.br). All cases had open biopsies performed and the available tissue was at least 0.5 cm in maximum size. The WHO 20083 criteria were applied, and B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with intermediate features between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma, was diagnosed if any of the following morphological and immunophenotypical patterns or combinations of patterns was present:

Pattern 1: Morphology consistent with classical Hodgkin lymphoma and immunohistochemistry showing expression of CD30 with or without expression of CD15, strong and diffuse expression of B-cell marker CD20 and/or CD79a, and/or expression of CD45.

Pattern 2: Morphology consistent with primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma, but neoplastic cells expressing CD30 and CD15 or EBER (EBV) by in situ hybridization (ISH), or with the absence of expression of CD20 with CD45 positivity, or the absence of CD45 with positivity for both CD20 and CD30.

Pattern 3: Morphological features of overlapping areas that look like primary mediastinal B-cell or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma mixed with those with morphological features of classical Hodgkin lymphoma or the presence of many Hodgkin/Reed–Sternberg-like cells admixed in an otherwise morphologically typical primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma with an aberrant immunophenotype such as CD15 expression or CD45 expression or CD20 intense/diffuse and CD45 negative; CD30 is usually positive and intense as in classical Hodgkin lymphoma or focal and weak as in primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma.

Pattern 4: As the WHO classification suggests, we have included in pattern 4 those cases of composite lymphoma with well-defined areas of both classical Hodgkin and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphomas in the same lymph node, as well as synchronous classical Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (involving different lymph nodes at the same time) and metachronous cases, with separate diagnosis of classical Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma occurring a few years apart (metachronous or sequential composite lymphomas). In this last situation, classical Hodgkin lymphoma followed by primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma is described as more frequent than the reverse chronological order.

The following morphological features were evaluated in each case: nodular growth with or without sclerosis; the extent and type of sclerosis (delicate, coarse or hyalinized); necrosis with or without neutrophilic infiltration; neoplastic cell types (large lymphoid cells, Reed–Sternberg-like cells, monomorphic, pleomorphic, centroblastic with amphophilic cytoplasm or clear cells); and type of cells in the background (lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, histiocytes, neutrophils). The neoplastic as well as the background cells were also evaluated by immunohistochemistry and ISH studies.

Immunohistochemistry and ISH

Immunohistochemical studies were performed using the Novolink polymer (Novocastra, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK) as the detection system, and an epitope-retrieval method was applied as needed for each specific antibody; diaminobenzidine was the chromogen. The primary antibodies used in this study are shown in Table 1. Paraffin sections were examined for the expression of Epstein–Barr viral RNA by ISH using the EBER-1 probe, as described previously.18

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) analysis was performed using a 3-μm-thick tissue section of the block, using probes specific for MYC, BCL2 and BCL6 rearrangements, as described previously.19, 20 For the detection of breakpoints (splits) in the MYC and BCL6 loci, specific LSI Dual Color Break-apart Rearrangement probes (Vysis, Abbott AG, Abbott Park, IL, USA) were applied. The t(14;18)(q32;q21) translocation was analyzed using a commercial dual ISI IGH/BCL2 probe (Vysis, Downers Grove, IL, USA). The slides were evaluated using spectrum orange and spectrum green filters (Chroma Technology GmbH, Fuerstenfeldbruck, Germany) on a Zeiss Axio Imager M1 fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany) using the assistance of Isis FISH Imaging Software (Metasystems, Altlussheim, Germany). A positive case was defined when the mean number of positive tiles detected was 3 s.d. above the mean of a negative control (reactive lymphoid tissue). The threshold established was 2.19% for MYC, 15.9% for BCL2, and 2.2% for BCL6 (the mean of the negative control group was 0.73, 7.8 and 0.75%, respectively).

Results

The 10 cases analyzed included 9 men and 1 woman with a mean age of 40 years and median age of 37 years (range 15–85 years). Eight cases presented with mediastinal mass, one with axillary lymph node enlargement and one with retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. Morphological and immunophenotypic features were divided into four patterns as described above (Tables 2 and 3). One case that presented in the mediastinum (case 10) was classified as a sequential composite lymphoma (pattern 4), as the patient initially presented with nodular sclerosis classical Hodgkin lymphoma in the mediastinum, and 14 months later, the tumor relapsed as a primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma, again in the mediastinum. Information about clinical and laboratory findings, stage, bone marrow infiltration, treatment and outcome are shown in Table 4.

Histological and Immunohistological Findings

The histological and immunohistological features of each case are summarized in Tables 2 and 3 and the overall immunoarchitectural pattern is presented in Table 4.

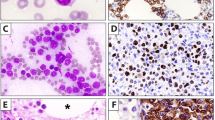

Pattern 1 was observed only in 1 case (case 1; Figure 1). The morphological features were typical of classical Hodgkin lymphoma: the tumor cells were large with an appearance consistent with classical Hodgkin (Reed–Sternberg, mononuclear variants and lacunar) cells and sclerotic bands delineating nodules. In some areas, confluent growth of Hodgkin cells resembling the syncytial variant of nodular sclerosis classical Hodgkin lymphoma was seen, while in other areas, focal necrosis was observed. An inflammatory background of eosinophils, neutrophils and lymphocytes was present. The neoplastic cells expressed CD30 and CD15 and exhibited strong and uniform positivity for CD20. In addition, CD79a and CD45 were also positive. The small lymphocytes were mainly B cells with admixed small T cells.

B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL), pattern 1 (case 1): histological sections show large atypical cells with Reed–Sternberg-like and centroblastic cells in a polymorphous background with eosinophils and punctate necrosis (a and b). Immunohistological studies show that the large atypical cells express CD45 (c), CD20 (d), CD30 (e) and CD15 (f). Original magnifications: × 200, × 400.

Pattern 2 was observed in cases 2 (Figure 2) and 3. The morphological features of these cases showed a monomorphous infiltrate of confluent sheet-like growth of large cells with irregular nuclear contours and clear cytoplasm. Most of these cells showed multiple, peripheral small nucleoli, although a minority of these cells exhibited a single central nucleolus with immunoblastic features. Classic Reed–Sternberg cells were not seen. In case 2, diffuse areas of sclerosis surrounded groups of neoplastic cells and, in focal areas, well-defined bands of compartmentalizing fibrosis were also present. In case 3, the solid sheets of neoplastic cells were separated by delicate fibrosis that did not form collagen bands. The background composition included a moderate inflammatory infiltrate of small lymphocytes and histiocytes with a scarcity of plasma cells. Eosinophils were identified only in case 3. Focal necrosis without neutrophilic debris was observed in case 2. Both cases showed immunoreactivity for CD30 and strong and diffuse expression of CD20; case 2 also showed positivity for CD15 and CD45. In contrast, case 3 lacked CD15 and was focally positive for CD45. The background small lymphocytes were a mixture of predominantly T cells (60%) and B cells (40%).

B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL), pattern 2 (case 2): histological sections show large atypical cells with immunoblastic and centroblastic morphology with diffuse sclerosis in a background of lymphocytes, histiocytes and few plasma cells (a and b). Immunohistological studies show that the large atypical cells express CD45 (c), CD20 (d), CD30 (e) and CD15 (f). Original magnifications × 200, × 400.

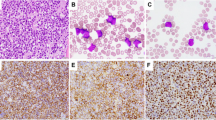

Pattern 3 was observed in 6 cases (cases 4–9) (Figure 3). This pattern presented a wider morphological range, with intricate mixtures of features of both classical Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma. The variation in cytological features ranged from medium to large cells with clear cytoplasm resembling centroblasts, whereas others resembled classical Reed–Sternberg cells; all were intimately associated with a diffuse and coarse fibrotic stroma. Case 5, in particular, showed a nodular architecture with very well-delineated nodules composed of thick fibrous bands. The inflammatory infiltrate was sparse with many lymphocytes and histiocytes, but fewer eosinophils and rare plasma cells. Focal necrosis without neutrophilic infiltrate was observed in cases 4, 6 and 9. There was a partial preservation of the lymph node parenchyma with hyperplastic follicles in case 4. In all cases with pattern 3, the neoplastic cells were positive for CD20, CD45 and CD30. A proportion of the Reed–Sternberg-like cells expressed CD15 in cases 5, 6 and 9, but the remainder of the cases lacked CD15. The neoplastic Reed–Sternberg-like cells were also strongly positive for at least one of the transcription factors BOB1, PAX5 and/or OCT2. Originally, some of these cases were diagnosed as B-cell lymphomas with Hodgkin-like pattern by the referring pathologist (cases 5 and 7). EBV was present in 2 cases as demonstrated by the expression of LMP-1 protein and/or EBER ISH in cases 7 and 8 (Table 3).

B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL), pattern 3 (case 6): histological sections show large atypical cells with anaplastic, Reed–Sternberg-like cells and centroblastic cells (a and b). Immunohistological studies show that the large atypical cells express CD45 (c), CD20 (d), CD30 (e) and CD15 (f). Original magnifications: × 200, × 400.

Pattern 4 was observed in 1 case (case 10) (Figure 4) as a metachronous classical Hodgkin lymphoma, followed by typical primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma. The initial mediastinal mass showed typical morphological and immunophenotypic features of nodular sclerosis classical Hodgkin lymphoma with Reed–Sternberg and lacunar cells that exhibited positivity for CD30 and CD15 with focal, weak and heterogeneous expression of CD20, but lacked CD45. B-cell transcription factors were variably positive: PAX5 was weakly positive, with the typical pattern of classical Hodgkin lymphoma, whereas BOB1 and OCT2 were negative in this original biopsy. After 1 year, disease recurrence in the mediastinum showed typical features of primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma. In this second biopsy of the mediastinal mass, there was a monomorphic proliferation of medium to large sized cells with round or ovoid nuclei and abundant clear cytoplasm. There were no Reed–Sternberg-like cells. The proliferation was associated with a diffuse fibrosis, with a minimal inflammatory infiltrate and no necrosis. The neoplastic cells were strongly positive for CD45, CD20, PAX5 and BOB1, with weak and focal positivity for CD30, and lacked CD15 and LMP-1. The findings were therefore typical of sequential primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma in a patient with a previous diagnosis of classical Hodgkin lymphoma.

B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL), pattern 4 (case 10, sequential composite type): histological sections of the initial biopsy show classical Hodgkin lymphoma, nodular sclerosis subtype with lacunar cells, Reed–Sternberg cells and mononuclear variants in a polymorphous background of eosinophils, histiocytes, lymphocytes and neutrophils (a). Immunohistological studies show that the Hodgkin cells express weak CD20 (b), CD30 (c) and CD15 (d). A subsequent biopsy of the mediastinum shows a monotonous and cohesive atypical large lymphoid proliferation with clear cytoplasm associated with geographic necrosis and delicate fibrosis without thickened sclerotic bands (e). Immunohistological studies show that these large atypical cells express CD45 (f), CD20 (g) and CD30 (h). Original magnification: × 200, × 400.

It is of interest that among the other immunohistological stains analyzed, 6 of 7 cases showed CD23 positivity in neoplastic cells. P63 expression was observed in 5 of 9 cases (56%). The expression of p63 was observed in both cases with pattern 2, in 2 of 4 cases with pattern 3, but also in case 1 that presented with pattern 1 resembling Hodgkin lymphoma. B-cell transcription factors BOB1, OCT2 and PAX5 showed a range of expression patterns: all three were strongly positive in 2 cases (cases 6 and 10 in second biopsy); PAX5 was positive in all 10 cases, except in case 4, in which a variable intensity from weak to strong was observed; all other cases displayed homogeneous and intense positive nuclear staining for PAX5. Weak/strong expression of OCT2 was observed in 6 of 8 cases and BOB1 in 4 of 10 cases. CD79a was also positive in all cases, MUM1/IRF4 in 6 of 10 and BCL6 in 5 of 9 cases.

All 10 cases lacked MYC, BCL2 and BCL6 rearrangements as assessed by FISH studies with appropriate positive controls.

Clinical follow-up was available in all cases, except in case 6. Two patients died: one due to sepsis in the initial phase of chemotherapy (R-CHOP) treatment (case 4) and the other due to progression of the disease 8 months after diagnosis (case 8), despite CHOP treatment ( × 6 series). These patients also had high-stage disease (stages IVa and III, respectively). The remaining seven patients achieved complete remission with combined modality treatments as shown in Table 5, with outcome periods from 10 to 28 months. Two of these patients (cases 5 and 7) also received bone marrow transplantation. One case (case 10), initially treated as classical Hodgkin lymphoma (ABVD) with only a partial clinical response, was switched to R-CHOP and radiotherapy 4 months later, and achieved complete clinical remission. Of these 7 cases, 6 (cases 1, 2, 3, 5, 9 and 10) received combined treatment with chemotherapy and radiotherapy (Table 5).

Discussion

Pathologists as well as hematologists have struggled with the challenges imposed by ‘gray zone lymphomas’ and have strived to appropriately classify as well as treat patients accordingly, although not always, successfully. In recognition of this dilemma, the WHO 2008 lymphoma classification addressed this problem by incorporating two borderline categories of aggressive B-cell lymphomas that cannot be further classified.3 In this study, we sought to address the clinicopathological and immunophenotypic features of 10 cases of unclassifiable B-cell lymphoma overlapping the spectrum between classical Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma. Our findings show that these lymphomas span a wide age range, occur most frequently in the mediastinum and show an immunoarchitectural pattern that is most often a combination of morphological and immunophenotypic features of both classical Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma/diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, although simultaneous as well as sequential composite lymphomas also exist in this milieu, as stated by the WHO 2008 classification.

Both classical Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma are two well-established clinicopathological entities.3 Typical morphological features of primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma include the presence of fine compartmentalizing sclerosis, neoplastic cells with abundant clear cytoplasm and/or multilobated nuclei and the presence of large cells with Reed–Sternberg cell-like morphology.21 The characteristic immunophenotype includes B-cell-associated antigens, with the majority of cases expressing BCL6, MUM1/IRF4, BCL2, CD23 and CD30, the last of which varies in intensity and is usually found in a subset of tumor cells.22 Classical Hodgkin lymphoma is characterized by the presence of Hodgkin cells (Reed–Sternberg cells and its variants) that are positive for CD30, and in more than 80% of the cases, for CD15, associated with an abundant mixed inflammatory infiltrate. The separation between these two entities is not always clearcut, but extremely important for therapeutic decision making.7

The overlap between primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and mainly the nodular sclerosis subtype of classical Hodgkin lymphoma includes clinical, pathological, genetic and molecular features. Both classical Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma share several clinicopathological characteristics such as female predominance, presence in young adulthood as well as frequent manifestation as an anterior mediastinal mass. The identification of molecular links through gene expression profiling further support the hypothesis that there is likely to be pathogenetic overlap and that these two entities may indeed represent the opposite ends of a continuum.16 Some studies have pointed out that despite the molecular overlap, protein expression in primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma appears to resemble that of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified, compared with classical Hodgkin lymphoma, particularly with regard to B-cell-associated antigens, which are strongly and homogeneously expressed in both mediastinal and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified, but usually show weak and heterogeneous expression in classical Hodgkin lymphoma.13 Quintanilla-Martinez et al7 propose that the presence or absence of a single marker or its variability should not alone be exploited to render a diagnosis of B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, and that familiarity with the acceptable spectrum of morphological and immunophenotypic features should be taken into consideration. For example, the expression of strong CD20 alone is not enough for an otherwise classical Hodgkin lymphoma to be diagnosed as B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma. In addition to the strong CD20, if the neoplastic cells were also positive for PAX5 and/or CD79a, then that diagnosis may be warranted.

Before the WHO 2008 classification, it was not always possible to classify accurately the borderline cases, and therefore, the inclusion of the B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, diagnoses in the WHO 2008 classification offers the pathologist a place to put difficult cases that cannot be further classified. Although this approach may make the pathologist more comfortable, it is imperative that a multidisciplinary team approach is used such that pathologists, hematologists/oncologists and radiologists are all closely involved in selecting an optimal treatment plan for the patient.

Our series of 10 B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with intermediate features between classical Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma were in accord with other published series.3, 15, 23 As described in the literature, our cases also showed male predominance (9 men and 1 women), mediastinal involvement in most cases (8/10 cases) in addition to which one case showed retroperitoneal adenopathy, while another exhibited axillary adenopathy. We organized these cases into four patterns based on clinicopathological and immunoarchitectural features, which allowed us to catalog systematically the spectrum of features in this spectrum of lymphomas. There was one case with pattern 1, two with pattern 2, six with pattern 3 (60%) and one with pattern 4. The morphology was variable, and although the most frequent morphological findings showed a mixture of features resembling primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma, it also contained Reed–Sternberg cells and variants. Similarly, immunophenotypic features were typically aberrant for either a primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma or a classical Hodgkin lymphoma: some cases presented with areas with the expression of markers typical of classical Hodgkin lymphoma and other areas typical of primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma, while other cases presented with an intricate mixture of both immunoarchitectural patterns. In the study of mediastinal gray zone lymphomas presented by Traverse-Glehen et al,24 58% of cases corresponded to pattern 3 and is very similar in frequency to our cohort.

The most common immunophenotype included the expression of CD20, CD30 and CD45, in addition to which CD15 and EBV were expressed in a subset of cases. CD20 and CD30 were the two most frequent markers expressed and were present in all cases in our series. CD45 was absent in only 1 case, which was remarkable for morphological features consistent with primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (pattern 2). Our cases also showed a high frequency of expression of CD79a (8/8) and PAX5 (10/10) even in Reed–Sternberg-like cells. BOB1 expression was found in 40% (4/10) of cases; its positivity is typical of mature B-cell lymphomas, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma, but absent or weak in classical Hodgkin lymphoma, although Reed–Sternberg cells may also rarely express BOB1.25 Hoeller et al26 proposed an algorithm to separate primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma, and to avoid the use of B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, by employing BOB1, CD79a and cyclin E that, according to these authors, enable accurate classification of the majority of cases of one or other type. It is worthwhile to note that in that study the authors included cases with the expression of CD20 and CD30, but the absence of CD15, without reference to CD45 status or morphological features resembling classical Hodgkin lymphoma. If these cases, however, were CD45 negative, they could simply represent classical Hodgkin lymphoma with CD20 expression. In our series, the use of BOB1 did not specifically contribute toward the separation of primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma or classical Hodgkin lymphoma, or indeed toward areas within a case that resembled primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma vs classical Hodgkin lymphoma. In addition, all of our cases also expressed CD79a and PAX5 expression, which is indicative of a B-cell immunophenotype in these cases.

The existence of B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma with EBV expression is described in the WHO 2008 classification.3 The frequency of EBV in this borderline category is yet to be determined as only a few cases have been reported in the literature. In the Traverse-Glehen et al24 series, 2 of 7 cases showed evidence of EBV, while Minami et al,25 and Quintanilla-Martinez et al7 reported one case each. Two cases in our series were associated with EBV, both exhibiting pattern 3. One of these patients was also the only woman in our series and had high-stage disease (stage III) with retroperitoneal involvement.

CD23 is frequently expressed in neoplastic cells of primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma.3 The expression of this marker in this lymphoma has been taken as evidence to suggest the origin of this lymphoma in ‘asteroid’ thymic B cells.22 This marker is usually absent in classical Hodgkin lymphoma, and often lends support for the diagnosis of primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma when typical morphological features and a B-cell immunophenotype are present. In our cohort, 5 of 6 cases were positive for CD23, with immunostaining in both monomorphically large and Reed–Sternberg-like neoplastic cells.

P63 expression has been reported in normal lymph nodes and in a subset of reactive lymphocytes in other tissues.27 Among hematolymphoid neoplasms, P63 protein has been described as positive in some types of non-Hodgkin lymphomas including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified,26, 28 primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma26 and anaplastic large-cell lymphoma,29 but is absent in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. P63 expression was observed in 5 of 8 of our cases (63%), which is slightly more frequent than in the series presented by Eberle et al,23 who found 49%. It is likely that P63 is expressed in cases biologically closer to primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma, although among the five positive cases in our series, no particular pattern was preferentially involved.

We also sought to address whether FISH studies would be useful in detecting MYC-, BCL2- or BCL6-related rearrangements, which are not infrequently found in aggressive B-cell lymphomas, particularly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. These rearrangements are especially pertinent to cases of B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with intermediate features between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma. Our cases, however, did not show these rearrangements.

The treatment of B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma is a challenge because its rarity limits experience not only with diagnosis and subclassification, but also with therapeutic approaches, which are yet to be established. Of the nine patients on whom we obtained complete clinical information, all were treated with chemotherapy protocols similar to those used for non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphomas, and six were also given radiotherapy; one patient underwent bone marrow transplantation. Two patients, who were treated only with chemotherapy, had high-stage disease and succumbed to their lymphoma. At the completion of this study, eight patients were alive and free of disease, although the follow-up period was relatively short at 10–28 months. One patient who received ABVD for classical Hodgkin lymphoma with no response (case 9) underwent a repeat biopsy of the mediastinum, which showed B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma; the regimen was altered to R-CHOP and radiotherapy, and the patient achieved complete remission. In general, our cases seem to reveal a better outcome than those described. This finding raises the important question of whether this category of lymphomas should be considered diffuse large B-cell lymphomas with aberrant immunophenotypes. Additional experience with larger cohorts of well-characterized patients over a longer follow-up period will likely be needed to unequivocally address this issue.

In summary, we presented a series of 10 well-characterized cases of B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma that add to our understanding of a new and difficult-to-diagnose WHO category of lymphomas. Our findings confirm and extend previous observations in the literature and enhance the morphological and immunophenotypic spectrum of this category of lymphomas. Further studies are nevertheless indicated to fully elucidate the disease heterogeneity and the therapeutic options for patients with this borderline category of aggressive lymphomas.

References

Carbone A, Gloghini A, Aiello A, et al. B-cell lymphomas with features intermediate between distinct pathologic entities. From pathogenesis to pathology. Hum Pathol 2010;41:621–631.

Sabattini E, Bacci F, Sagramoso C, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues in 2008: an overview. Pathologica 2010;102:83–87.

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al (eds). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues 2008.

Poppema S, Kluiver JL, Atayar C, et al. Report: workshop on mediastinal grey zone lymphoma. Eur J Haematol Suppl 2005;66:45–52.

Rudiger T, Jaffe ES, Delsol G, et al. Workshop report on Hodgkin's disease and related diseases (‘grey zone’ lymphoma). Ann Oncol 1998;9 (Suppl 5):S31–S38.

Rudiger T, Gascoyne RD, Jaffe ES, et al. Workshop on the relationship between nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin's lymphoma and T cell/histiocyte-rich B cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol 2002;13 (Suppl 1):44–51.

Quintanilla-Martinez L, de Jong D, de Mascarel A, et al. Gray zones around diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Conclusions based on the workshop of the XIV meeting of the European Association for Hematopathology and the Society of Hematopathology in Bordeaux, France. J Hematopathol 2009;2:211–236.

Garcia JF, Mollejo M, Fraga M, et al. Large B-cell lymphoma with Hodgkin's features. Histopathology 2005;47:101–110.

Rosenwald A, Staudt LM . Gene expression profiling of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2003;44 (Suppl 3):S41–S47.

Rosenwald A, Wright G, Leroy K, et al. Molecular diagnosis of primary mediastinal B cell lymphoma identifies a clinically favorable subgroup of diffuse large B cell lymphoma related to Hodgkin lymphoma. J Exp Med 2003;198:851–862.

Savage KJ, Monti S, Kutok JL, et al. The molecular signature of mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma differs from that of other diffuse large B-cell lymphomas and shares features with classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2003;102:3871–3879.

Calvo KR, Traverse-Glehen A, Pittaluga S, et al. Molecular profiling provides evidence of primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma as a distinct entity related to classic Hodgkin lymphoma: implications for mediastinal gray zone lymphomas as an intermediate form of B-cell lymphoma. Adv Anat Pathol 2004;11:227–238.

Marafioti T, Pozzobon M, Hansmann ML, et al. Expression pattern of intracellular leukocyte-associated proteins in primary mediastinal B cell lymphoma. Leukemia 2005;19:856–861.

Hasserjian RP, Ott G, Elenitoba-Johnson KS, et al. Commentary on the WHO classification of tumors of lymphoid tissues (2008): ‘gray zone’ lymphomas overlapping with Burkitt lymphoma or classical Hodgkin lymphoma. J Hematopathol 2009;2:89–95.

Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, et al. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood 2011;117:5019–5032.

Oschlies I, Burkhardt B, Salaverria I, et al. Clinical, pathological and genetic features of primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphomas and mediastinal gray zone lymphomas in children. Haematologica 2011;96:262–268.

Liang X, Greffe B, Cook B, et al. Gray zone lymphomas in pediatric patients. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2010;14:57–63.

Bacchi MM, Bacchi CE, Alvarenga M, et al. Burkitt lymphoma in Brazil: strong association with Epstein–Barr virus. Mod Pathol 1996;9:63–67.

Chuang SS, Ye H, Du MQ, et al. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry in distinguishing Burkitt lymphoma from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with very high proliferation index and with or without a starry-sky pattern: a comparative study with EBER and FISH. Am J Clin Pathol 2007;128:558–564.

Oschlies I, Klapper W, Zimmermann M, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in pediatric patients belongs predominantly to the germinal-center type B-cell lymphomas: a clinicopathologic analysis of cases included in the German BFM (Berlin–Frankfurt–Munster) Multicenter Trial. Blood 2006;107:4047–4052.

Lamarre L, Jacobson JO, Aisenberg AC, et al. Primary large cell lymphoma of the mediastinum. A histologic and immunophenotypic study of 29 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1989;13:730–739.

Calaminici M, Piper K, Lee AM, et al. CD23 expression in mediastinal large B-cell lymphomas. Histopathology 2004;45:619–624.

Eberle FC, Salaverria I, Steidl C, et al. Gray zone lymphoma: chromosomal aberrations with immunophenotypic and clinical correlations. Mod Pathol 2011;24:1586–1597.

Traverse-Glehen A, Pittaluga S, Gaulard P, et al. Mediastinal gray zone lymphoma: the missing link between classic Hodgkin's lymphoma and mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:1411–1421.

Minami J, Dobashi N, Asai O, et al. Two cases of mediastinal gray zone lymphoma. J Clin Exp Hematop 2010;50:143–149.

Hoeller S, Zihler D, Zlobec I, et al. BOB.1, CD79a and cyclin E are the most appropriate markers to discriminate classical Hodgkin's lymphoma from primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Histopathology 2010;56:217–228.

Di Como CJ, Urist MJ, Babayan I, et al. p63 expression profiles in human normal and tumor tissues. Clin Cancer Res 2002;8:494–501.

Hedvat CV, Teruya-Feldstein J, Puig P, et al. Expression of p63 in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2005;13:237–242.

Gualco G, Weiss LM, Bacchi CE . Expression of p63 in anaplastic large cell lymphoma but not in classical Hodgkin's lymphoma. Hum Pathol 2008;39:1505–1510.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the Medical Centers and colleagues who provided the clinical and follow-up information: Alexandre Tafuri, MD, André de A Corinthi, MD, Dairton Miranda, MD, Daniela Derossi, MD, Eduardo Serafini, MD, Evyo Abreu e Lima, MD, Marcus Aurelho de Lima, MD, Maria Cecília Ferro, MD, Maria Cristina de Araújo Neves, MD, Rosa Arcuri, MD, Rubens Barros Costa, MD and Rubens Rodriguez, MD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gualco, G., Natkunam, Y. & Bacchi, C. The spectrum of B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma: a description of 10 cases. Mod Pathol 25, 661–674 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2011.200

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2011.200

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Optimized multiplex immunofluorescence for the characterization of tumor immune microenvironment in neoplastic paraffin-preserved tissues

Journal of Cell Communication and Signaling (2023)

-

Mediastinal large B cell lymphoma and surrounding gray areas: a report of the lymphoma workshop of the 20th meeting of the European Association for Haematopathology

Virchows Archiv (2023)

-

Comparison of pediatric and adult lymphomas involving the mediastinum characterized by distinctive clinicopathological and radiological features

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Neues von der Histopathologie des Hodgkin-Lymphoms

Der Onkologe (2014)

-

B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma without mediastinal disease: mimicking nodular sclerosis classical Hodgkin lymphoma

Medical Molecular Morphology (2013)