Abstract

Endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas are malignancies that affect uterus; however, their biological behaviors are quite different. This distinction has clinical significance, because the appropriate therapy may depend on the site of tumor origin. The purpose of this study is to evaluate four different scoring methods of p16INK4a immunohistochemical staining in distinguishing between primary endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas from limited sizes of tissue specimens. A tissue microarray was constructed using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue from hysterectomy specimens, including 14 endocervical adenocarcinomas and 21 endometrial adenocarcinomas. Tissue array sections were immunostained with a commercially available antibody of p16INK4a. Avidin–biotin complex method was used for antigens visualization. The staining intensity and area extent of the immunohistochemistry was evaluated using the semiquantitative scoring system. Of the four scoring methods for p16INK4a expression, Method Nucleus, Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus, and Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus showed significant (P values <0.05), but Method Cytoplasm did not show significant (P=0.432), frequency distinction between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas. In addition, Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus had the highest overall accuracy rate (80%) for diagnostic distinction among these four score-counting methods. According to the data in this tissue microarray study, Method Nucleus is the most convenient and efficient method to distinguish between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas. Although Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus as well as Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus also revealed statistically significant results, they are relatively more inconvenient due to complicated score calculating means on the basis of mixed cytoplasmic and nuclear p16INK4a expressions. Method Cytoplasm is of no use in the diagnostic distinction between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The histomorphologic overlap of endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas can make differentiation difficult on hematoxylin-and-eosin staining in small preoperative biopsy or curetting specimens. Ascertaining the site of cancer origin may be difficult, but plays an important role in guiding treatment. For the endometrial adenocarcinomas, staging is surgical. Treatment requires hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, usually bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, and likely excision of all tissue involved. For advanced endometrial adenocarcinomas, radiation, hormone, or cytotoxic therapy may also be indicated. In contrast, for primary endocervical adenocarcinomas, staging is clinical. Treatment usually includes initial radical hysterectomy and bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy with or without adjuvant radiation therapy for the localized cancer; if cancer is widely metastasized, treatment is primarily chemotherapy. Management of recurrence should be individualized, depending on the location of disease and the type of previous therapy.1, 2

Previous studies have shown that certain immunohistochemical markers may be helpful in distinguishing between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas. A panel of four traditional markers has previously been proposed to make the distinction. A positive estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and vimentin, as well as a negative carcinoembryonic antigen result indicate an endometrial adenocarcinoma; a negative estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and vimentin, as well as a positive carcinoembryonic antigen result indicate an endocervical adenocarcinoma. There are, however, many unexpected aberrant immunoexpressions not characteristic of either primary endocervical adenocarcinomas or endometrial adenocarcinomas, when using this conventional four-marker panel (estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor/vimentin/carcinoembryonic antigen). No study has identified one marker that clearly and consistently makes this distinction in all cases.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

Recent work has focused on other markers, such as p16INK4a, which may express in different intensities, staining patterns and subcellular localizations in various malignancies and tissues. It is also reported that endocervical adenocarcinomas tends to be positively and diffusely expressed by p16INK4a, whereas endometrial adenocarcinomas tends to be negatively or focally expressed by p16INK4a in routine whole-sectioned tissue slides.9, 10, 11 To date, there is yet no consensus to define the optimal scoring methods of p16INK4a immunoexpression in various tissue samples, especially in those small sizes of preoperative biopsy or curetting specimens of endocervix or endometrium. In this study, we proposed four score-calculating methods, which were defined on the basis of the subcellular localizations of p16INK4a expression, including (1) Method Cytoplasm: independent cytoplasmic scoring alone, irrespective of nuclear stains, (2) Method Nucleus: independent nuclear scoring alone, irrespective of cytoplasmic stains, (3) Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus: scoring using the higher score of either Method Cytoplasm or Method Nucleus, and (4) Method Mean of Cytoplasm and Nucleus: scoring using the mean of Method Cytoplasm and Method Nucleus. Our objective was to propose appropriate and simple scoring methods and to report that these methods can be easily applied to p16INK4a immunohistochemistry as a diagnostic adjunct in clinical discrimination between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas.

Materials and methods

Study Materials

The study material consisted of slides and selected formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks from 35 hysterectomy specimens retrieved from the archives of the Tissue Bank, Clinical Research Center, Chung-Shan Medical University Hospital. These specimens of known origin, endocervix or endometrium, were accessioned between 2004 and 2007. The cases studied included endometrial adenocarcinomas, endometroid type (n=21), as well as endocervical adenocarcinomas, endocervical type (n=14). Two board-certified pathologists (CP Han and LF Kok) reviewed all hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained slides for these cases. A slide with representative tumor was selected and circled from each case. In the next step, the area corresponding to the selected area on the slide was also circled on the block with an oil marker pen. All these donors’ tissue blocks were sent to the commercial Biochiefdom International Co. Ltd, Taiwan for tissue microarray. They were cored with a 1.5 mm diameter needle and transferred to a recipient paraffin block. The recipient block was sectioned at 5 μm, and transferred to silanized glass slides.

Immunohistochemical Staining

Using the avidin–biotin complex technique, immunohistochemistry and antigen retrieval methods were applied in the same manner as described in previous literature.12 Briefly, all the 1.5 mm and 5 μm cores of tissue array specimens embedded in paraffin slice on coated slides, were washed in xylene to remove the paraffin, rehydrated through serial dilutions of alcohol, followed by washings with a solution of PBS (pH 7.2). All subsequent washes were buffered via the same protocol. Treated sections were then placed in a citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and heated in a microwave for two 5-min sessions. The samples were then incubated with a monoclonal anti-mouse p16INK4a antibody (F12, sc-1661; Santa Cruz; 1:200 dilution) for 60 min at 25°C. The conventional streptavidin peroxidase method (LSAB Kit K675; DAKO, Copenhagen, Denmark) was performed for signal development and the cells were counter-stained with hematoxylin. Negative controls were obtained by excluding the primary antibody, and positive controls were simultaneously obtained by staining tissues of squamous cell carcinoma of uterine cervix. This slide was mounted with gum for examination and capture by the Olympus BX51 microscopic and DP71 Digital Camera System for study comparison.

Scoring of Immunohistochemistry Staining Results

The core of specimens on the tissue microarray slides were examined and scored using a two-headed microscope. As scoring algorithms of the p16INK4a immunohistochemistry have not been optimized and standardized, we interpreted the cytoplasmic and nuclear staining separately, as well as a mix-up of cytoplasmic and nuclear staining collectively. We also adopted the German semiquantitative scoring system in considering the staining intensity and area extent, which has been widely accepted and used in previous studies.13, 14, 15, 16 Every tumor was given a score according to the intensity of the nuclear or cytoplasmic staining (no staining=0; weak staining=1; moderate staining=2; strong staining=3) and the extent of stained cells (0%=0; 1–10%=1; 11–50%=2; 51–80%=3; 81–100%=4). The final immunoreactive score was determined by multiplying the intensity and extent of positivity scores of stained cells, with the minimum score of 0 and a maximum score of 12.15, 16, 17

Statistical Analysis

The threshold for differentiating between final positive and negative immunostaining was set at 4 for interpretation. This optimal cut-off value was determined by using the receiver operating characteristic curve analysis (Metz; Zweig and Campbell) in this study. Score of 4 points or greater was considered positive for p16INK4a expression. A negative stain was classified as having an immunostaining score of 0–3 (essentially negative) and indicated a diagnosis of an endometrial adenocarcinoma; whereas a positive stain was classified as having an immunostaining score of 4–12 (at least moderately positive in at least 11–50% of cells) and indicated a diagnosis of an endocervical adenocarcinoma. A χ2 or Fisher's exact test was performed to test the frequency difference of p16INK4a immunostaining (positive vs negative) between groups of two primary adenocarcinomas (endocervical adenocarcinomas vs endometrial adenocarcinomas). A nonparametric analysis of Mann–Whitney U-test was used to test the immunostaining raw scores between the two adenocarcinomas, given the fact that the analytical immunohistochemistry scores were not normally distributed. In addition, we also examined associations among the four different scoring methods. The nonparametric Spearman's rho correlation coefficient was used to analyze associations between pairs of these four types of p16INK4a scores. Data were analyzed using standard statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All tests were two sided and the significance level was 0.05.

To evaluate and compare the patterns of p16INK4a expression in making a diagnostic distinction of primary endocervical adenocarcinomas from primary endometrial adenocarcinomas, the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and the positive predictive value and negative predictive value were compared and displayed. Sensitivity is defined as the probability of positive p16INK4a stain in primary endocervical adenocarcinomas. Specificity is, on the other hand, defined, as the probability of negative p16INK4a stain in primary endometrial adenocarcinomas.18 Overall accuracy is the proportion of true diagnosis of endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas in total number of p16INK4a scoring tests. Positive predictive value is the probability that a patient with a positive p16INK4a expression has a primary adenocarcinoma of endocervical origin. Negative predictive value is the probability that a person with a negative p16INK4a expression has a primary adenocarcinoma of endometrial origin.18 To assess whether the test results were statistically different from each other based on correct diagnosis, McNemar's test was performed. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

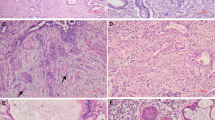

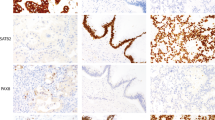

For evaluation of p16INK4a immunohistochemistry, nuclear and cytoplasmic stains were taken into account separately as well as collectively for all cases. Hematoxylin-and-eosin staining and immunoreactivities for p16INK4a can be identified in representatives of endocervical adenocarcinomas (Figure 1) and endometrial adenocarcinomas (Figure 2). The p16INK4a expression in endocervical adenocarcinomas was observed both in nuclei and cytoplasm with varying degrees of staining intensity and area extent. Nuclear staining was predominant in 7 out of 14 cases (Figure 1a–c), both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining were codominant in 5 out of 14 cases (Figure 1d), and cytoplasmic staining was predominant in 2 out of 14 cases. On the other hand, the p16INK4a expression in endometrial adenocarcinomas was also observed both in nuclei and cytoplasm with varying degrees of staining intensity and area, except for 3 out of 21 cases with a score of 0. Nuclear staining was predominant in 7 out of 21 cases (Figure 2a), both nuclear and cytoplasmic stainings were codominant in 6 out of 21 cases, and cytoplasmic staining was predominant in 5 out of 21 cases (Figure 2b–d). One case of endometrial adenocarcinoma showed a patchy staining pattern with a mix of prominent positive and negative staining areas. There was also focally weak positive nuclear staining, which intermingled with moderate cytoplasmic staining in some glands, but absence of staining in other areas (Figure 2b).

Immunohistochemical analysis of p16INK4a staining in endocervical adenocarcinomas. Photomicrographs (a–c) revealed individual representatives with more prominent p16INK4a staining at nucleus than that at cytoplasm. (a) Focally weakly positive nuclear staining intensity, no cytoplasmic staining, (b) focally moderately positive nuclear staining intensity, no cytoplasmic staining, (c) diffusely moderately positive nuclear staining intensity, as well as diffusely weakly positive cytoplasmic staining intensity. Photomicrograph (d) revealed one case with equal intensities in both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining, which manifested by diffusely strongly positive nuclear staining intensity, diffusely strongly positive cytoplasmic staining. All photomicrographs (a–d) were taken in high-powered, × 400.

Immunohistochemical analysis of p16INK4a staining in endometrial adenocarcinomas. Photomicrograph (a) revealed one case with more prominent p16INK4a staining at nucleus, which manifested by focally weakly positive nuclear staining intensity, no cytoplasmic staining. Photomicrographs (b–d) revealed representatives with both cytoplasmic and nuclear staining showing variable patterns and intensities. (b) Patchy pattern with focally weakly positive nuclear staining intensity, and focally moderately cytoplasmic staining intensity. (c) Focally weakly positive nuclear staining, diffusely moderately positive cytoplasmic staining intensity. (d) Focally moderately positive nuclear staining intensity, diffusely strongly positive cytoplasmic staining intensity. All photomicrographs (a–d) were taken in high-powered, × 400.

Regardless of the intensity of p16INK4a staining, the area extent of the cytoplasmic staining varied from 0 to 100% in both endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas, whereas the area extent of nuclear staining varied from 40 to 90% in endocervical adenocarcinomas, and 0–60% in endometrial adenocarcinomas. The area extent of p16INK4a staining can be subdivided by binary tiers with diffusely staining (81–100% positive, 4 points) and negative to focally staining (0–80% positive, 0–3 points). Of the 21 endometrial adenocarcinoma specimens, one case (1/21) revealed diffusely strong cytoplasmic staining, but focally strong nuclear staining. The rest of the cases (20/21) revealed varying degrees of intensity and varying area extents of staining in both cytoplasmic and nuclear subcellular compartments. Of the 14 endocervical adenocarcinoma specimens, one case showed diffusely strong cytoplasmic and nuclear staining. The remaining cases (13/14) showed varying degrees of intensity and area extents of staining in both cytoplasmic and nuclear subcellular compartments.

The immunohistochemistry results of these four p16INK4a scoring methods, (1) Method Cytoplasm, (2) Method Nucleus, (3) Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus, and (4) Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus, are summarized in Table 1. By using score of 4 as a cut-off point, except for Method Cytoplasm, all other 3 scoring methods based on N, dominant C or N, and mean of C plus N, showed significant frequency differences between immunostaining (positive vs negative) in tissues from the two adenocarcinomas (endocervical vs endometrial) in origin. Individually, (1) Method Cytoplasm stained positive in 5 out of 14 (36%) endocervical adenocarcinoma tumors and 4 out of 21 (19.0%) stained positive in endometrial adenocarcinoma tumors (P=0.432), with median staining score and range of 2 (0–12) and 2 (0–12), respectively (P=0.249); (2) Method Nucleus stained positive in 11 out of 14 (79%) endocervical adenocarcinoma tumors and 7 out of 21 (33%) stained positive in endometrial adenocarcinoma tumors (P=0.015), with median staining score and range of 5 (2–12) and 2 (0–9), respectively (P=0.001); (3) Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus stained positive in 12 out of 14 (86%) endocervical adenocarcinoma tumors and 8 out of 21 (38%) stained positive in endometrial adenocarcinoma tumors (P=0.007), with median staining score and range of 6 (2–12) and 2 (0–12), respectively (P=0.002); and (4) Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus stained positive in 10 out of 14 (71%) endocervical adenocarcinoma tumors and 3 out of 21 (14%) stained positive in endometrial adenocarcinoma tumors (P=0.001), with median staining score and range of 4.25 (2–12) and 2 (0–11), respectively (P=0.001). In summary, Method Cytoplasm for p16INK4a immunohistochemistry was not a statistically significant method to distinguish between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas. However, the other three methods for p16INK4a immunohistochemistry, Method Nucleus, Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus, and Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus, resulted in significant frequency differences (P<0.05) between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas.

The associations between pairs of these four types of p16INK4a scoring methods in endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas were also explored and shown in Figure 3 and Table 2. The immunostaining scores based on Method Cytoplasm were significantly positive correlated with those based on Method Nucleus in endometrial adenocarcinomas (Spearman's rho=0.53, P=0.014), but the correlation was not significant in endocervical adenocarcinomas (Spearman's rho=−0.128, P=0.663; Figure 3a1 and b1). Method Cytoplasm scores exhibited significant positive correlation with Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus scores in endometrial adenocarcinomas (Spearman's rho=0.763, P<0.001), but the correlation was not significant in endocervical adenocarcinomas (Spearman's rho=0.032, P=0.914; Figure 3a2 and c1). Method Cytoplasm scores exhibited significant positive correlation with Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus scores in endometrial adenocarcinomas (Spearman's rho=0.859, P<0.001), but the correlation was not significant in endocervical adenocarcinomas (Spearman's rho=0.456, P=0.101; Figure 3a3 and d1). Method Nucleus scores exhibited significant positive correlation with Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus scores in both endometrial adenocarcinomas (Spearman's rho=0.853, P<0.001) and endocervical adenocarcinomas (Spearman's rho=0.905, P<0.001; Figure 3b2 and c2). Moreover, Method Nucleus scores exhibited significant positive correlation with Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus scores in both endometrial adenocarcinomas (Spearman's rho=0.863, P<0.001) and endocervical adenocarcinomas (Spearman's rho=0.713, P=0.004; Figure 3b3 and d2). Finally, Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus scores exhibited significant positive correlation with Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus scores in both endometrial adenocarcinomas (Spearman's rho=0.926, P<0.001) and endocervical adenocarcinomas (Spearman's rho=0.85, P<0.001; Figure 3c3 and d3).

Scatter plots showing the relationships between pairs of four types of p16INK4a scoring methods in endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas. (1) a1, b1 revealed the correlation of immunostaining scores between Method Cytoplasm and Method Nucleus. Method Cytoplasm was positively correlated with Method Nucleus in endometrial adenocarcinomas, but was not in endocervical adenocarcinomas (2) a2, c1 revealed the correlation of immunostaining scores between Method Cytoplasm and Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus. Method Cytoplasm was positively correlated with Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus in endometrial adenocarcinomas but was not in endocervical adenocarcinomas. (3) a3, d1 revealed the correlation of immunostaining scores between Method Cytoplasm and Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus. Method Cytoplasm was positively correlated with Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus in both endometrial adenocarcinomas endocervical adenocarcinomas. (4) b2, c2 revealed the correlation of immunostaining scores between Method Nucleus and Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus. Method Nucleus was positively correlated with Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus in both endometrial adenocarcinomas and endocervical adenocarcinomas. (5) b3, d2 revealed the correlation of immunostaining scores between Method Nucleus and Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus. Method Nucleus was positively correlated with Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus in both endometrial adenocarcinomas and endocervical adenocarcinomas. (6) c3, d3 revealed the correlation of immunostaining scores between Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus and Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus. Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus was positively correlated with Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus in both endometrial adenocarcinomas and endocervical adenocarcinomas.

Clinicians may also find interesting the following parameters when judging the test effectiveness of p16INK4a expression as a marker for diagnostic distinction between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas. Table 3 shows the diagnostic performance of these four different scoring methods for measuring p16INK4a expression in distinguishing 14 endocervical adenocarcinomas from 21 endometrial adenocarcinomas. (1) When using Method Cytoplasm, the sensitivity of positively stained endocervical adenocarcinomas was 36% (5/14) and positive predictive value was 56%, whereas the specificity of negatively stained endometrial adenocarcinomas was 81% (17/21) and negative predictive value was 65%. The overall accuracy rate was 63%. (2) When using Method Nucleus, the sensitivity was 79% (11/14) and positive predictive value was 61%, whereas the specificity was 67% (14/21) and negative predictive value was 82%. The overall accuracy rate was 71%. (3) When using Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus, the sensitivity was 86% (12/14) and positive predictive value was 60%, whereas the specificity was 62% (13/21) and negative predictive value was 87%. The overall accuracy rate was 71%. (4) When using Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus, the sensitivity was 71% (10/14) and positive predictive value was 77%, whereas the specificity (18/21) was 86% and negative predictive value was 82%. The overall accuracy rate was 80%, the highest among the four scoring methods.

Discussion

Distinguishing between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas before planning the patient treatment is clinically important. When the tumor involves both the uterine endometrium and the endocervix, it becomes difficult to distinguish the primary site of the tumor during preoperative assessment of the limited sizes of biopsy or curetting specimens. In this study, we evaluate p16INK4a expression patterns in both endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas by using a tissue microarray. We investigate more advantageous, appropriate, and easier means of score-counting methods of p16INK4a immunoreactivities. We also want to determine whether it could be used as a simple and convenient ancillary tool in distinguishing these two types of gynecologic cancers in Taiwanese women. Our valuable domestic data can be extrapolated to women in general and will be helpful in referring and managing such cases worldwide.

The p16INK4a (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 4) is a tumor suppressor protein that binds to cyclin-cdk4/6 complexes, which blocks kinase activity and inhibits progression to the S phase of the cell cycle in the nucleus.17, 19, 20 However, interpretation of immunohistochemistry of p16INK4a staining results is complicated because of its unclear biological significance of cytoplasmic staining and lack of universal accepted algorithm in scoring methodology. Cytoplasmic reactivity is often regarded as unexpected, unspecific event.21 Some consider only nuclear p16INK4a labeling in tumor cells to be positive and ignore cytoplasmic staining.10, 22, 23 Others state that both nuclear and cytoplasmic immunoreactivities in tumor cells are characteristic and are indeed due to p16INK4a expression.24, 25, 26, 27, 28 It has also been reported that strong cytoplasmic staining in mammary carcinomas is associated with negative prognostic factors, such as low differentiation, p53, Ki-67 labeling, etc. We have learned that despite nuclear expression, p53 tumor suppressor protein is localized on cell cytoplasm, where it is regarded as a way of functional inactivation.29, 30, 31 From our data, we cannot draw any conclusion yet about the biological significance of cytoplasmic p16INK4a expression. The knowledge about the functional meaning of cytoplasmic p16INK4a expression is still limited and further large-scale studies are recommended to evaluate its authentic role at various subcellular compartments in human normal tissues and tumors.

There are variable scoring methods including computer-based plans in literatures, and still seems to be no generally accepted protocols in research laboratories and clinical practices for rating and scoring the immunostaining results. Comparing commercially derived computer-based programs with the conventional analyses by pathologists, there is a lack of optimized and standardized immunohistochemistry scoring algorithms. As a result, the objective accuracy did not significantly improve clinical outcome measures.24, 25, 26, 27, 28

There are a variety of quantitative scoring methods of p16INK4a expression using various cut-off thresholds in literature. Without mentioning the grading of intensity, Vallmanya Llena reports the cut-off point for p16INK4a expression to be 15% positively staining extent.29 Fregonesi defines the cut-off point for p16INK4a expression to be 5% cells stained positively.22 Khoury used the positive staining area >50% as a cutoff.10 All of them took both nuclear and cytoplasmic p16INK4a immunohistochemistry staining into consideration. However, Huang regarded any nuclear labeling of p16INK4a to be positive, irrespective of cytoplasmic staining.30 Kommoss only used the nuclear staining patterns for p16INK4a evaluation.31 Milde-Langosch defined the 12-tier scoring system which was also used in this study.32 In addition, we investigated four score-counting methods of p16INK4a immunohistochemistry staining and evaluated which means could be effective diagnostic adjunct tools in the distinction between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas. These results can potentially be applied to future clinically diagnostic techniques, when using p16INK4a immunohistochemistry.

McCluggage and Mittal stated that a diffuse, strong staining pattern of p16INK4a, involving nearly all tumor cells tends to be an endocervical adenocarcinoma, whereas focal, patchy staining pattern of p16INK4a involving 0–50% of cells tends to be an endometrial adenocarcinoma in routine whole-sectioned tissue slides.9, 11 It has also been reported that strong cytoplasmic staining might overlap with weaker nuclear p16INK4a expression, and cytoplasmic and nuclear staining may correlate closely in most cases of breast cancer.31 We found the patchy pattern of p16INK4a immunohistochemistry staining in one case of endometrial adenocarcinoma in this study. Endometrial adenocarcinomas may have seemed to overexpress p16INK4a beyond the limited 1.5 mm core area and therefore mimic a diffuse pattern of endocervical adenocarcinoma primary. Although some cases revealed either nuclear or cytoplasmic staining predominant, the others showed nuclear and cytoplasmic staining codominant. In addition, there could be various degrees of staining intensity and varying areas of staining percentage in the same tissue section. These discrepancies of p16INK4a expression in different subcellular compartments (cytoplasmic vs nuclear) may have caused significant difficulties in the scoring process. As a result, we did not use the patchy or diffuse pattern of p16INK4a immunohistochemistry staining as a diagnostically distinctive criterion between endocervical and endometrial adenocarcinomas in this tissue microarray study. Instead, we preferred to use the semiquantitative scoring system in considering the three-tier staining intensity and four-tier staining area by multiplying both, yielding a range of score 0–12 points. We then divided the results by an appropriate cut-off threshold of 4 to a two-tier of negative (0–3 points) or positive (4–12 points) for interpretation.

In addition, there is no consensus on how to weigh the appropriate ratio between nuclear and cytoplasmic staining in counting total scores of the mixed cytoplasmic and nuclear p16INK4a expression results. Of the 14 endocervical adenocarcinoma and 21 endometrial adenocarcinoma tissue samples in this study, we found that 3 of the 4 scoring methods (Method Nucleus, Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus, and Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus) showed significant frequency differences (P<0.05), whereas the fourth scoring method (Method C) did not show a significant difference (P>0.05) in distinguishing between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas (Table 1). We cannot completely yet rule out the possibility of the indigenous heterogeneity within individual tumors, leading to different p16INK4a expression patterns in various areas within the same tissue samples, because of the limited number of cases (14 endocervical adenocarcinoma and 21 endometrial adenocarcinomas tissues) and limited core size (1.5 mm) of the tumor specimens in tissue microarray. However, our data in Table 2 showed that the p16INK4a expression in endometrial adenocarcinoma cytoplasms is significantly correlated with that in endometrial adenocarcinoma nuclei (P=0.014), but p16INK4a expression in endocervical adenocarcinoma cytoplasms is not significantly correlated with that in endocervical adenocarcinoma nuclei (P=0.663). In short, both cytoplasmic staining and nuclear staining correlate well, but tend to be weaker or negative in endometrial adenocarcinomas. However, both cytoplasmic staining and nuclear staining correlate poorly, but tend to be stronger or positive in endocervical adenocarcinomas.

For the p16INK4a-marker test effectiveness of endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas discrimination, the goal is to minimize the chance or probability of false-positive and false-negative results, and to maximize the probability of true positive and true negative results. According to our data, Method Cytoplasm does not show significant frequency difference in making distinction between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas (P=0.432). The sensitivity of Method Cytoplasm was 36%, indicating a high false-negative rate, whereas, the specificity of Method Cytoplasm is 81%, indicating a favorable low false-positive rate. Both the negative predictive value (65%) and the positive predictive value (55.6%) do not provide valuable information. However, the scoring of p16INK4a expression using the other three methods, including Method Nucleus, Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus, and Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus shows significant frequency differences in making distinction between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas (P<0.05). The highest sensitivity is 86% using Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus, the highest specificity is 85.7% using Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus, the highest negative predictive value is 87% using Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus, whereas the highest positive predictive value is 77.0% using Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus. Notably, Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus has the highest overall accuracy (80%).

In summary, even though p16INK4a-scoring methods using Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus and Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus can provide promising results, Method Nucleus based on nuclear staining alone seems to be a sufficient, simple, and useful scoring means in distinguishing between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas. Despite the finite number of cases, our data provide significant and valuable reference as to verify that p16INK4a with appropriate scoring methods can be applied as a useful member of diagnostic panel to distinguish between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas from limited sizes of tissue specimens.

It is concluded that distinguishing between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas can often be accomplished by careful gross and histologic examinations, but some cases remain uncertain with indeterminate tumor origins or histomorphologic overlap. True diagnosis may often require the use of ancillary immunohistochemistry panel stains. The p16INK4a marker tends to be positively and diffusely expressed in endocervical adenocarcinomas, but tends to be negatively or focally expressed in endometrial adenocarcinomas. However, there is still a lack of optimized consensus or standardized for p16INK4a immunohistochemistry scoring scenarios. According to the scientific data, three out of the four total methods, which includes (1) Method Dominant Cytoplasm or Nucleus, (2) Method Mean of Cytoplasm plus Nucleus and (3) Method Nucleus, helps to distinguish between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas, but the last method, (4) Method Cytoplasm, is of no use in the diagnostic differentiation between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas. Method Nucleus, based on independent nuclear scoring alone, irrespective of cytoplasmic stains, can conveniently and effectively distinguish between endocervical adenocarcinomas and endometrial adenocarcinomas.

References

Luran JR, Bidus MA, Elkas JC . Uterine cancer, cervical and vaginal cancer. In: Berek RS (ed). Novak's Gynecology, 14th edn. Lippincott: Philadelphia, 2007, pp 1343–1402.

Wehling M . Translational medicine: science or wishful thinking? J Transl Med 2008;6:31.

Zaino RJ . The fruits of our labors: distinguishing endometrial from endocervical adenocarcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2002;21:1–3.

Castrillon DH, Lee KR, Nucci MR . Distinction between endometrial and endocervical adenocarcinoma: an immunohistochemical study. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2002;21:4–10.

McCluggage WG, Sumathi P, McBride HA, et al. A panel of immunohistochemical stains, including carcinoembryonic antigen, vimentin, and estrogen receptor, aids in the distinction between primary endometrial and endocervical adenocarcinomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2002;21:11–15.

Alkushi A, Irving J, Hsu F, et al. Immunoprofile of cervical and endometrial adenocarcinomas using a tissue microarray. Virchows Arch 2003;442:271–277.

Yao CC, Kok LF, Lee MY, et al. Ancillary p16(INK4a) adds no meaningful value to the performance of ER/PR/Vim/CEA panel in distinguishing between primary endocervical and endometrial adenocarcinomas in a tissue microarray study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2009 Jan 20, Springer doi:10.1007/s00404-008-0859-1 [e-pub ahead of print].

Miller RT . Endocervical vs endometrial adenocarcinoma: update on useful immunohistochemical markers. THE FOCUS—Immunohistochemistry 2003 April; 1–2, http://www.ihcworld.com/_newsletter/2003/focus_apr_2003.pdf [e-publication].

McCluggage WG, Jenkins D . p16 immunoreactivity may assist in the distinction between endometrial and endocervical adenocarcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2003;22:231–235.

Khoury T, Tan D, Wang J, et al. Inclusion of MUC1 (Ma695) in a panel of immunohistochemical markers is useful for distinguishing between endocervical and endometrial mucinous adenocarcinoma. BMC Clin Pathol 2006;6:1.

Mittal K, Soslow R, McCluggage WG . Application of immunohistochemistry to gynecologic pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2008;132:402–423.

Cheng YW, Wu MF, Wang J, et al. Human papillomavirus 16/18 E6 oncoprotein is expressed in lung cancer and related with p53 inactivation. Cancer Res 2007;67:10686–10693.

Remmele W, Schicketanz K-H . Immunohistochemical determination of estrogen and progesterone receptor content in human breast cancer. Computer-assisted image analysis (QIC score) vs subjective grading (IRS). Pathol Res Pract 1993;189:862–866.

de Matos LL, Stabenow E, Tavares MR, et al. Immunohistochemistry quantification by a digital computer-assisted method compared to semiquantitative analysis. Clinics 2006;61:417–424.

Han CP, Lee MY, Tzeng SL, et al. Nuclear Receptor Interaction Protein (NRIP) expression assay using human tissue microarray and immunohistochemistry technology confirming nuclear localization. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2008;27:25.

Kamoi S, AlJuboury MI, Akin MR, et al. Immunohistochemical staining in the distinction between primary endometrial and endocervical adenocarcinomas: another viewpoint. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2002;21:217–223.

Xu MH, Deng CS, Zhu YQ, et al. Role of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in aberrant crypt foci-adenoma-carcinoma sequence. World J Gastroenterol 2003;9:1246–1250.

Bodner G, Schocke MF, Rachbauer F, et al. Differentiation of malignant and benign musculoskeletal tumors: combined color and power Doppler US and spectral wave analysis. Radiologe 2002;223:410–416.

Musgrove EA, Lee CSL, Cornish AL, et al. Antiprogestin inhibition of cell cycle progression in T47-D breast cancer cells is accompanied by induction of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21. Mol Endocrinol 1997;11:54–66.

Milde-Langosch K, Riethdorf L, Bamberger A-M, et al. P16/MTS1 and pRb expression in endometrial carcinomas. Virchows Arch 1999;434:23–28.

Camp RL, Chung GG, Rimm DL . Automated subcellular localization and quantification of protein expression in tissue microarrays. Nat Med 2002;8:1323–1327.

Fregonesi PA, Teresa DB, Duarte RA, et al. p16 INK4A immunohistochemical overexpression in premalignant and malignant oral lesions infected with human papillomavirus. J Histochem Cytochem 2003;51:1291–1297.

Corless CL, Schroeder A, Griffith D, et al. PDGFRA mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors: frequency, spectrum and in vitro sensitivity to imatinib. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:5357–5364.

Powell EL, Leoni LM, Canto MI, et al. Concordant loss of MTAP and p16/CDKN2A expression in gastroesophageal carcinogenesis: evidence of homozygous deletion in esophageal noninvasive precursor lesions and therapeutic implications. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:1497–1504.

Ranade K, Hussussian CJ, Sikorski RS, et al. Mutations associated with familial melanoma impair p16INK4 function. Nat Genet 1995;10:114–116.

Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J . Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with longterm follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:52–68.

Franquemont DW . Differentiation and risk assessment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Clin Pathol 1995;103:41–47.

Borden EC, Baker LH, Bell RS, et al. Soft tissue sarcomas of adults: state of the translational science. Clin Cancer Res 2003;9:1941–1956.

Vallmanya Llena FR, Laborda Rodríguez A, Lloreta Trull J, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of p53, p21, p16, and cyclin D1 in superficial bladder cancer. Actas Urol Esp 2006;30:754–762.

Huang HY, Huang WW, Lin CN, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of p16INK4A, Ki-67, and Mcm2 proteins in gastrointestinal stromal tumors: prognostic implications and correlations with risk stratification of NIH consensus criteria. Ann Surg Oncol 2006;13:1633–1644.

Kommoss S, du Bois A, Ridder R, et al. Independent prognostic significance of cell cycle regulator proteins p16INK4a and pRb in advanced-stage ovarian carcinoma including optimally debulked patients: a translational research subprotocol of a randomised study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Ovarian Cancer Study Group. Br J Cancer 2007;96:306–313.

Milde-Langosch K, Bamberger AM, Rieck G, et al. Overexpression of the p16 cell cycle inhibitor in breast cancer is associated with a more malignant phenotype. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2001;67:61–70.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Han, CP., Kok, LF., Wang, PH. et al. Scoring of p16INK4a immunohistochemistry based on independent nuclear staining alone can sufficiently distinguish between endocervical and endometrial adenocarcinomas in a tissue microarray study. Mod Pathol 22, 797–806 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2009.31

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2009.31

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Keratin 14-high subpopulation mediates lung cancer metastasis potentially through Gkn1 upregulation

Oncogene (2019)

-

TIM-4 promotes the growth of non-small-cell lung cancer in a RGD motif-dependent manner

British Journal of Cancer (2015)

-

CUL4A facilitates hepatocarcinogenesis by promoting cell cycle progression and epithelial-mesenchymal transition

Scientific Reports (2015)

-

Significance of p53 expression in background endometrium in endometrial carcinoma

Virchows Archiv (2015)

-

FXYD6: a novel therapeutic target toward hepatocellular carcinoma

Protein & Cell (2014)