Abstract

Following primary infection, all eight human herpesviruses persist lifelong in the human host. However, a mapping of all anatomic sites of human herpesvirus persistence is lacking. Fresh tissue specimens representing approximately 40 major anatomic sites from eight autopsies were screened using a recently developed real-time PCR method for detection of all eight human herpesviruses. Patients with evidence of active herpesvirus infection (herpes simplex 1 (HSV-1), herpes simplex 2 (HSV-2), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6), herpesvirus 7 (HHV-7), and herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)) at the time of death were excluded to avoid detection of widely disseminated infection. Despite this precaution, widespread HSV-1 positivity (with blood positivity) was detected in one case—an elderly male who died of cardiac arrest. In a middle-aged male with HIV-AIDS, HSV-1 was found in neural and pharyngeal tissues, skin, cartilage, bone, and urinary bladder, whereas in two other cases, HSV-1 was restricted to neural tissues. HSV-2 was detected in a single site, the anus, in the male with HIV-AIDS. VZV was detected only twice, once in the adrenal gland and once in the small intestine. CMV was detected in three cases, most commonly in nasal mucosa, trachea, thyroid, intestine, and liver. EBV was detected in all eight cases, especially in nasal mucosa, tonsil, spleen, lymph node, tongue, and intestine, but in only two of six whole-blood specimens. HHV-6, like EBV, was detected in all eight cases, most commonly in salivary glands, thyroid, stomach, intestines, liver, and pancreas. HHV-7, like EBV and HHV-6, was detected in all eight cases, most commonly in salivary glands, tonsil, lymph nodes, and bone marrow. HHV-8 was detected in only two sites (both lymph nodes) from two cases. Herpesviruses were detected in three of six whole-blood specimens, including HSV-1, EBV, HHV-6, and HHV-7. These results represent the most comprehensive mapping of herpesvirus tissue distribution in humans reported to date.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

There are eight known human herpesviruses (herpes simplex 1 (HSV-1), herpes simplex 2 (HSV-2), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6), herpesvirus 7 (HHV-7), and herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8). Following symptomatic primary infection, all herpesviruses maintain a state of lifelong asymptomatic latent persistence in the host with sporadic symptomatic reactivation. Each herpesvirus preferentially induces disease in specific tissues, for example, HSV-1 and HSV-2 in oral and genital mucosa, respectively, VZV in skin and mucous membranes, EBV in lymphoid tissue, CMV in lung and kidney, HHV-6 in skin, and HHV-8 in skin and lymphoid tissue. On the other hand, herpesviruses are found in other tissues during latent persistence, for example, HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV in neural tissues, and EBV and HHV-6 in lymphoid tissues. Although a number of sites of latent herpesvirus persistence have been identified, no systematic survey of persistent herpesvirus infection in all human tissues from single individuals has been reported.

We have recently developed a highly sensitive and specific PCR method for detection and identification of all eight known human herpesviruses.1 This nested PCR-based assay utilizes a set of degenerate consensus primers complementary to the highly conserved herpesvirus DNA polymerase gene.2 By applying this method to more than 40 different tissues obtained from each of eight unrestricted autopsy cases, we have been able to identify systematically all sites of herpesvirus persistence in the adult human.

Materials and methods

Autopsy Tissues

Samples (1 cm3) of fresh tissue representing approximately 40 individual tissue types were collected from each study case at the time of post-mortem examination after obtaining proper consent. To prevent crosscontamination of tissues, each sample was collected with a sterile scalpel blade and forceps. To remove as much blood as possible, each sample was briefly rinsed in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.2) and immediately transferred to individual sterile 15 ml tubes containing 5 ml preservative solution (STF, Streck Labs, La Vista, NE, USA). Samples were held at 4°C overnight until DNA extraction the following day. DNA was extracted individually from each sample using sterile technique under a class II biohazard hood with a commercial kit (QIamp DNA Mini Kit, Qiagen Corp., Valencia, CA, USA). DNA yield and purity of each specimen was determined by standard UV spectrophotometry. DNA samples were stored at −20°C until use in real-time PCR.

Nested PCR Assay

Control herpesvirus DNA was obtained by DNA extraction (QIamp DNA Mini Kit, Qiagen Corp., Valencia, CA, USA) from the following sources: HSV-1 (American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Rockville, MD, USA), HSV-2 (ATCC), VZV (Ellen strain; ATCC), EBV (B95-8 (type 1), Jijoye (type 2); ATCC), CMV (AD169 strain; ATCC), HHV-6 (U1102 strain (type A), gift of Dr Philip Pellett (CDC); Z-29 strain (type B); Advanced Biotechnologies, Columbia, MD, USA), HHV-7 (H7-4 strain; Advanced Biotechnologies), and HHV-8 (BCBL-1; NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Rockville, MD, USA). Amplicons obtained by panherpes PCR of each reference herpesvirus above were cloned into a TA cloning vector (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) and identity confirmed by DNA sequencing and comparison of sequence with that found in GenBank. These vectors serve as herpesvirus DNA standards. Purified DNA (1 μg) previously obtained from autopsy tissues was subjected to nested PCR (EasyStart DNA PCR Kit, Molecular Bioproducts Corp., San Diego, CA, USA; Taq DNA polymerase, Sigma-Genosys Corp., St Louis, MO, USA) with a set of 10 degenerate herpesvirus DNA polymerase PCR primers: 1-GAYTTYGCNAGYYTNTAYCC, 2-TCCTGGACAAGCAGCARN YSGCNMTNAA, 3-GAYTTYGCIAGYYTITAYCC, 4-TCCTGGACAAGCAGCARIYSGCIMTIAA, 5-TGTAACTCGGTGTAYGGNTTYACNGGNGT, 6-TGTAACTCGGTGTAYGGITTYACIGGIGT, 7-GTCTTGCTCACCAGNTCNACNCCYTT, 8-GTCTTGCTCACCAGITCIACICCYTT, 9-CACAGAGTCCGTRTCNCCRTADAT, and 10-CACAGAGTCCGTRTCICCRTAIAT.2 These sequences include nucleotide symbols R=A/G,Y=C/T, M=A/C, S=C/G, D=A/G/T, and N=A/C/G/T, and I=inosine. First-round PCR with panherpes primers 1–4, 7, and 8 consisted of 55 cycles of 94°C for 2 min 40 s, 94°C for 20 s, 46°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, with a final 72°C extension for 7 min. Second-round (nested) PCR with primers 5, 6, 9, and 10 consisted of 55 cycles of 94°C for 2 min 40 s, 94°C for 20 s, 46°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 20 s, with a final 72°C extension for 7 min. To avoid DNA contamination, DNA extraction and PCR were performed with sterile technique with aerosol-resistant pipette tips under a level 2 biohazard hood and an Airclean 600 Workstation (Raleigh, NC, USA) each located in two different laboratories in different campus buildings. As further assurance of noncontamination, both positive and negative control PCR tubes were run with each PCR batch.

Dot-Blot Nucleic Acid Hybridization

PCR product (5 μl) from each sample, denatured by sodium hydroxide solution, was spotted onto nylon membranes (GeneScreen Plus, Dupont-NEN, Boston, MA, USA).1 Following membrane prehybridization, digoxigenin-labeled specific probe (HSV probes are 65 bp, all other probes are the same size as their PCR products) was heat-denatured, mixed in 6 ml hybridization buffer (5 × SSC, 0.1% N-lauroylsarcosine, 0.02% SDS, 1% blocking reagent), added to the membranes, and incubated for 6 h at 68°C. The membranes were washed twice in 2 × SSC–0.1% SDS for 5 min at room temperature, and twice in 0.1 × SSC–0.1% SDS for 30 min at 68°C. The membranes were next incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) followed by chemiluminescent substrate according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA), exposed to X-OMAT AR radiographic film (Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA) for up to 10 min, and developed.

Real-Time PCR

Primer sequences were: HSV-1, ATACCGACCACACCGACGA and ACAACTCCCTAACCCCTGCT; HSV-2, TTCCCCCGTGGCTCAATATT and ACGCGCCGGGGCAGGTCT; VZV, GGCGGAACTTTCGTAACCAA and CCCCATTAAACAGGTCAACAAAA; EBV, CCAAGAAGGTGGCCCAGA and CCTGCCTCCATCACCCTG; CMV, TCGCGCCCGAAGAGG and CGGCCGGATTGTGGATT; HHV-6, TCGAAATAAGCATTAATAGGCACACT and CGGAGTTAAGGCATTGGTTGA; HHV-7, ATGTACCAATACGGTCCCACTTG and AGAGCTTGCGTTGTGCATGTT; and HHV-8, TGCCCTGAGCCAGTTTGTC and AATAAACGCCGGGTCTGTACC. Probe sequences were: HSV-1, AGGGGCCATTTTACGAGGAGGA; HSV-2, TTATGCCTATCCCCGGTTGGACGA; VZV, TCCAACCTGTTTTGCGGCGGC; EBV, CCGCAGATGACCCAGGAGAAGGCC; CMV, CACCGACGAGGATTCCGACAACG; HHV-6, CCAAGCAGTTCCGTTTCTCTGAGCCA; HHV-7, AGCACGCACGGCAATAACTCTAGAAG; and HHV-8, AACATGCCGCACACCGTCAG. All probes were dual-labeled with a 5′ fluorochrome (FAM, TET, or ROX) and a 3′ black hole (BHQ) quencher (Sigma Genosys). Real-time PCR was set up with the Sigma Real-Time PCR Kit and JumpStart Taq Ready Mix (Sigma). Final primer and probe concentrations were 0.2 μmol/l. Real-time PCR began with a 2 min period at 95°C to activate the Taq polymerase, followed by 55 cycles of 95°C for 15 s; 60°C for 30 s; and 72°C for 30 s using a Cepheid SmartCycler real-time PCR instrument. Generally speaking, in those instances in which very faint (ambiguous) signals were obtained by nested dot-blot assay, samples were also analyzed by real-time PCR to confirm (or reject) positivity. Specifically, a few samples with faint HHV-7 positivity by dot-blot were confirmed as positive by real-time PCR, and a few samples with very faint VZV positivity were judged as negative after negative real-time PCR results were obtained.

Results

The eight autopsy cases consisted of four males and four females ranging in age from 14 to 73 (Table 1). Two patients (1 and 6) died with HIV-AIDS. Bacterial and/or fungal sepsis appears to have contributed to death in two cases, whereas myocardial infarction and/or cardiopulmonary failure contributed to death in six cases. In no case was a diagnosis of herpesvirus infection, pre- or post mortem, entertained.

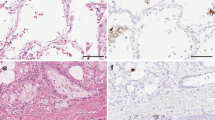

HSV-1 was detected in four cases within peripheral (non-CNS) neural tissues, nasal mucosa, cartilage, marrow, skin, and bone. In two cases (1 and 3), HSV-1 was found in multiple tissues, a finding most consistent with active infection. In the remaining two positive cases (2 and 6), HSV-1 was detected only in neural tissues, a finding more consistent with latent infection. In contrast to HSV-1, HSV-2 was found only in a single tissue (anus) from case 1, a male with HIV-AIDS who also had evidence of active HSV-1 infection. VZV was detected in only four sites (dorsal root ganglion, spinal cord, adrenal gland, small intestine) from three cases. Not unexpectedly, EBV was detected in many sites in all eight cases, most commonly lymphoid tissues (including thymus), tongue, nasal mucosa, intestines, and liver, although seldom found in neural and genitourinary tissues. CMV was detected in three cases within multiple tissues. In two cases, CMV was confined to nasal mucosa, trachea, thyroid, intestine, and liver, whereas in case 1, CMV was detected in multiple tissues including nasal mucosa, trachea, thyroid, lung, urinary bladder, urethra, mediastinal node, and anus. HHV-6, like EBV, was detected in multiple tissues from all eight cases, most commonly in salivary glands and gastrointestinal tissues. HHV-7, like EBV and HHV-6, was detected in all eight cases, primarily in salivary glands and lymphoid tissues. HHV-8 was detected in only two lymph nodes from two cases, a 43-year-old HIV-positive male and a 73-year-old HIV-negative male (Table 2).

Discussion

Largely by virtue of their ability to maintain lifelong infectious persistence following primary infection, the human herpesviruses are widely distributed throughout the world. For example, based upon seroepidemiologic surveys, it is estimated that more than 90% of all adult humans are infected with EBV. Reactivation of herpesviral replication from latency may occur throughout life, and leads not only to infection of naïve contacts but also to significant host morbidity and mortality. Although many anatomical sites of human herpesvirus persistence have been discovered, no complete mapping of all anatomical sites of herpesvirus latent persistence is currently available.

Primary HSV-1 infection of immunocompetent persons is characterized by lesions of the oral mucosa, followed by latent persistence within neurons of cervical and cranial nerve sensory ganglia.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 In some cases, HSV-1 and HSV-2 can be found in brain tissue.12 Viral reactivation can lead to recurrent mucocutaneous disease, whereas dissemination may lead to widespread organ involvement, including esophagus, lower gastrointestinal tract, trachea, lungs, brain, eyes, and skin. Primary infections with the herpes simplex viruses are characterized by localized mucocutaneous vesicular eruptions, with HSV-1 eruptions in the oral region and HSV-2 eruptions in the genital region. Virus then spreads along the sensory nerves to sensory root ganglia where latency is established in ganglionic neurons.9, 10, 11, 13 HSV-1 was detected in four of eight cases. In two cases, HSV-1 was detected only in neural tissues (dorsal root ganglion, spinal cord, sympathetic ganglion, and peripheral nerve), whereas in two other cases, HSV-1 was detected in multiple tissues. Although review of the medical records and autopsy findings revealed no evidence of active herpes simplex infection in either case, it is clear that occult HSV-1 viremia with dissemination occurred at the time of death. Although the weak PCR positivity noted in some tissues is likely owing to blood contamination, other tissues in which the PCR signal was significantly stronger than that of whole blood may represent sites of HSV-1 replication. These tissues included neural tissues (peripheral nerve, sympathetic and dorsal root ganglia, spinal cord), digestive system (tongue, parotid gland, stomach, large intestine), urinary system (kidney, urinary bladder), nasal mucosa, trachea, pleura, thymus, vena cava, skin, smooth muscle (diaphragm), cartilage, and bone.

Primary HSV-2 infection of immunocompetent persons is characterized by lesions of the genital mucosa, followed by latent persistence within sacral ganglia. In some cases, spinal cord involvement may lead to ascending myelitis, meningitis, and autonomic dysfunction. Anorectal involvement may be seen in homosexual males. In the present study, HSV-2 was found in only one site, the anus of a 43-year-old male with HIV-AIDS. Given their relative inaccessibility during prosection, sacral ganglia were not examined in this study.

Primary VZV infection is characterized by lesions of the oral mucosa and skin, followed by latent persistence within cranial nerve sensory ganglia (geniculate, trigeminal), dorsal root ganglia, and the olfactory bulb.9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16 Dissemination may lead to widespread organ involvement, including the eye, brain, lung, myocardium, and liver. Primary VZV infection, most often acquired in early childhood, is characterized by fever and a diffuse maculopapular rash. Although VZV DNA can be detected in many different cell types during active infection, latency seems largely to be established in neural tissues, particularly in non-neuronal cells of sensory ganglia.9, 10, 11, 13, 14 In the present study, VZV was detected in three of eight cases within only four sites: dorsal root ganglion, spinal cord, adrenal gland, and small intestine. VZV may maintain latency within the ganglion cells of the adrenal medulla and the parasympathetic ganglia of the small intestine.

EBV first infects oropharyngeal mucosa and lymphoid tissues, and establishes latent persistence in lymphoid tissues, most notably tonsils and lymph nodes, as well as peripheral blood B cells. Immunocompromised persons are at risk for development of EBV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome or B-cell lymphoma. Numerous sites of EBV persistence were detected in the present study in all eight cases, with the most common sites of involvement being blood and lymphoid tissues. Although primary childhood infection with EBV often goes unrecognized, infection in young adults, termed infectious mononucleosis, is characterized by fever, pharyngitis, and cervical lymphadenopathy. EBV DNA is commonly detected in saliva, tonsils, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood from healthy adults. Latency is established in small B-lymphocytes, with lytic infection rarely detected in oral epithelium.17, 18 In the present study, EBV as expected was detected in all eight cases within numerous tissues, most prominently hematolymphoid tissues (lymph node, spleen, tonsil, thymus, bone marrow, blood), pharyngeal tissues (tongue, parotid gland), and digestive tissues (esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, liver, pancreas).

In children and adults, CMV probably first infects oropharyngeal tissues, and may persist in salivary glands, renal tubular cells, endothelium, alveolar macrophages, blood monocytes, and marrow cells.19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 In contrast, congenital (in utero) infection leads to infection of the central nervous system. In the immunocompromised host, CMV lesions may be found in numerous organs, including lung, brain, liver, gastrointestinal tract, and kidney. CMV infection is most often acquired by young adulthood and often presents as a mononucleosis syndrome similar to that caused by EBV. Sites of CMV latency have been clearly established but may include marrow myeloid progenitors, spleen, arterial smooth muscle, and bronchoalveolar cells.32, 33, 34, 35, 36 CMV DNA has also been detected in a wide variety of other cell types including hepatocytes, renal tubular and glomerular cells, splenic red pulp cells, and pancreatic acinar cells from healthy adults.37 In the present study, CMV was detected in three of eight cases within nasopulmonary tissues (nasal mucosa, trachea, lung), thyroid gland, small and large intestine, anus, urinary tissues (urethra, urinary bladder), and lymph node. In two cases, CMV was detected in only a few tissues (nasal mucosa, trachea, thyroid, intestine, liver) that may represent sites of latency. In contrast, in one HIV-positive case, CMV was also detected in other sites including lung, lymph node, urinary bladder, and urethra, and thus may represent active infection.

HHV-6 is a ubiquitous virus that probably first infects oropharyngeal tissue during early childhood causing high fever and a characteristically evanescent rash. Latent persistence likely occurs in salivary glands and lymphoid tissues.38, 39, 40 In adults, HHV-6 infection may present with a mononucleosis-like syndrome with acute lymphadenitis.41 Disseminated infection may be associated with hepatitis, pneumonia, marrow suppression, and encephalitis. HHV-6 has also been detected, albeit at low levels, in Hodgkin's lymphoma and angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy,42 and has been implicated in multiple sclerosis.43 HHV-6 infection is common in early childhood, when it presents as a febrile illness with rash, known as roseola. In healthy adults, HHV-6 DNA has been detected in saliva and salivary gland epithelium.44, 45 HHV-6 has also been detected in lymph nodes from adults with a form of lymphadenitis.46 In organ transplant recipients, HHV-6 has been detected in bile duct and gastroduodenal epithelium.47 In HIV-AIDS, HHV-6 may be detected in a wide range of tissues, including lung, lymph node, spleen, liver, kidney, and brain.48 In the present study, HHV-6 was detected in all eight cases, in a wide variety of tissues including pharyngeal tissues (tongue, parotid and submandibular glands, nasal mucosa, tonsil), pulmonary tissues (lung and pleura), thyroid and adrenal glands, lymphoid tissues (blood, spleen, lymph node), muscle (skeletal and smooth), gastrointestinal tissues (esophagus, stomach, small and large intestine, liver, gall bladder, pancreas), urinary tissues (kidney, urinary bladder), and vagina. The presence of HHV-6 in vagina suggests the possibility of sexual and perinatal transmission of HHV-6 infection to sexual partners and newborns, respectively.

Primary HHV-7 infection in children is very common and is characterized by high fever. Most persons have been infected by adulthood, with adult seroprevalence rates of 60–80%. Oral transmission leads to active replication in the oropharynx. Virus has been obtained from peripheral blood T cells and monocytes, saliva, salivary glands, and uterine cervical secretions.49, 50 HHV-7 DNA has been detected in saliva and salivary gland epithelium from healthy adults.45, 51 By immunohistochemistry, HHV-7 antigen has been detected in lymph node, tonsils, liver, and kidney of healthy adults.52 In the present study, HHV-7 was detected in all eight cases, in pharyngeal tissues (submandibular and parotid gland, tonsil), hematologic tissues (marrow, blood, spleen), gastrointestinal tissues (stomach, small intestine), and vagina. As with HHV-6, the presence of HHV-7 in vagina suggests the possibility of sexual and perinatal transmission of HHV-7.

The clinical characteristics of primary HHV-8 infection have not been clearly defined. Similarly, little information is available about sites of HHV-8 persistence. However, based upon the presence of the virus in blood monocytes, lymphoid tumors, and lymphatic endothelial tumors, it is likely that HHV-8 may persist in hematopoietic and lymphatic tissues. In the present study, HHV-8 was detected in lymph node tissue from two cases. As HHV-8 infection was originally thought to be confined to patients with HIV-infected homosexual males, it is noteworthy that HHV-8 was present not only in tissue from an middle-aged HIV-positive male but also in an elderly Caucasian male with no clinical or pathological evidence of immunodeficiency. Although the clinical characteristics of primary HHV-8 infection have not been clearly elucidated, a recent report suggests that some cases of mononucleosis in childhood may be owing to HHV-8 infection.53 As HHV-8 was discovered in cutaneous Kaposi's sarcoma tissues from patients with HIV-AIDS, most of our information regarding tissue distribution of HHV-8 is based upon analysis of tissues from severely immune compromised patients with HIV-AIDS and thus may not reflect the situation in healthy adults. In patients with HIV-AIDS and KS, HHV-8 DNA can be detected in saliva, peripheral blood monocytes, lymphoid tissues, normal skin, prostate gland, and bone marrow.54, 55, 56, 57 Since in the present study HHV-8 was detected only twice in lymph nodes, we suggest that the site of HHV-8 latency is in peripheral lymphoid tissues.

Determination of all anatomical sites of viral latency or persistence in humans is a remarkably tedious procedure as it not only requires a robust assay but also access to all (preferably fresh) tissues from each donor. We have previously developed a robust PCR assay for detection and identification of all eight known human herpesviruses and have now applied this assay to DNA isolated from fresh post-mortem tissues representing approximately 40 anatomical sites from eight randomly selected patients aged 14–73 years who died of causes unrelated to herpesvirus infection.

References

Hudnall SD, Chen T, Tyring SK . Species identification of all eight human herpesviruses with a single nested PCR assay. J Virol Methods 2004;116:19–26.

Ehlers B, Borchers K, Grund C, et al. Detection of new DNA polymerase genes of known and potentially novel herpesviruses by PCR with degenerate and deoxyinosine-substituted primers. Virus Genes 1999;18:211–220.

Thompson RL, Sawtell NM . Herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript gene promotes neuronal survival. J Virol 2001;75:6660–6675.

Bustos DE, Atherton SS . Detection of herpes simplex virus type 1 in human ciliary ganglia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2002;43:2244–2249.

Thompson RL, Sawtell NM . Replication of herpes simplex virus type 1 within trigeminal ganglia is required for high frequency but not high viral genome copy number latency. J Virol 2000;74:965–974.

Lokensgard JR, Bloom DC, Dobson AT, et al. Long-term promoter activity during herpes simplex virus latency. J Virol 1994;68:7148–7158.

Daheshia M, Feldman LT, Rouse BT . Herpes simplex virus latency and the immune response. Curr Opin Microbiol 1998;1:430–435.

Lehner T, Wilton JM, Shillitoe EJ . Immunological basis for latency, recurrences and putative oncogenicity of herpes simplex virus. Lancet 1975;2:60–62.

Theil D, Horn AK, Derfuss T, et al. Prevalence and distribution of HSV-1, VZV, and HHV-6 in human cranial nerve nuclei III, IV, VI, VII, and XII. J Med Virol 2004;74:102–106.

Theil D, Paripovic I, Derfuss T, et al. Dually infected (HSV-1/VZV) single neurons in human trigeminal ganglia. Ann Neurol 2003;54:678–682.

Mitchell BM, Bloom DC, Cohrs RJ, et al. Herpes simplex virus-1 and varicella-zoster virus latency in ganglia. J Neurovirol 2003;9:194–204.

Gordon L, McQuaid S, Cosby SL . Detection of herpes simplex virus (types 1 and 2) and human herpesvirus 6 DNA in human brain tissue by polymerase chain reaction. Clin Diagn Virol 1996;6:33–40.

Croen KD, Ostrove JM, Dragovic LJ, et al. Patterns of gene expression and sites of latency in human nerve ganglia are different for varicella-zoster and herpes simplex viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1988;85:9773–9777.

Annunziato PW, Lungu O, Panagiotidis C . Varicella zoster virus in human and rat tissue specimens. Arch Virol Suppl 2001;17:135–142.

Abendroth A, Arvin A . Varicella-zoster virus immune evasion. Immunol Rev 1999;168:143–156.

Lungu O, Annunziato PW, Gershon A, et al. Reactivated and latent varicella-zoster virus in human dorsal root ganglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995;92:10980–10984.

Gratama JW, Oosterveer MA, Zwaan FE, et al. Eradication of Epstein–Barr virus by allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: implications for sites of viral latency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1988;85:8693–8696.

Schmidt CW, Misko IS . The ecology and pathology of Epstein–Barr virus. Immunol Cell Biol 1995;73:489–504.

Jarvis MA, Nelson JA . Mechanisms of human cytomegalovirus persistence and latency. Front Biosci 2002;7:1575–1582.

Bolovan-Fritts CA, Mocarski ES, Wiedeman JA . Peripheral blood CD14(+) cells from healthy subjects carry a circular conformation of latent cytomegalovirus genome. Blood 1999;93:394–398.

Adam E, Melnick JL, DeBakey ME . Cytomegalovirus infection and atherosclerosis. Cent Eur J Public Health 1997;5:99–106.

Guetta E, Guetta V, Shibutani T, et al. Monocytes harboring cytomegalovirus: interactions with endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and oxidized low-density lipoprotein. Possible mechanisms for activating virus delivered by monocytes to sites of vascular injury. Circ Res 1997;81:8–16.

Kondo K, Mocarski ES . Cytomegalovirus latency and latency specific transcription in hematopoietic progenitors. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl 1995;99:63–67.

Kondo K, Kaneshima H, Mocarski ES . Human cytomegalovirus latent infection of granulocyte–macrophage progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994;91:11879–11883.

Kondo K, Xu J, Mocarski ES . Human cytomegalovirus latent gene expression in granulocyte–macrophage progenitors in culture and in seropositive individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996;93:11137–11142.

Sindre H, Tjoonnfjord GE, Rollag H, et al. Human cytomegalovirus suppression of and latency in early hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood 1996;88:4526–4533.

Kondo K, Mocarski ES . Cytomegalovirus latency and latency-specific transcription in hematopoietic progenitors. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl 1995;99:63–67.

Fajac A, Vidaud M, Lebargy F, et al. Evaluation of human cytomegalovirus latency in alveolar macrophages. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;149:495–499.

Taylor-Wiedeman J, Sissons JG, Borysiewicz LK, et al. Monocytes are a major site of persistence of human cytomegalovirus in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Gen Virol 1991;72:2059–2064.

Toorkey CB, Carrigan DR . Immunohistochemical detection of an immediate early antigen of human cytomegalovirus in normal tissues. J Infect Dis 1989;160:741–751.

Jordan MC . Latent infection and the elusive cytomegalovirus. Rev Infect Dis 1983;5:205–215.

Sissons JG, Bain M, Wills MR . Latency and reactivation of human cytomegalovirus. J Infect 2002;44:73–77.

Dworniczak S, Ziora D, Kaminski J, et al. Broncho-alveolar lavage cells are the most significant reservoir of human cytomegalovirus genome. Pneumonol Alergol Pol 2003;71:512–520.

Khaiboullina SF, Maciejewski JP, Crapnell K, et al. Human cytomegalovirus persists in myeloid progenitors and is passed to the myeloid progeny in a latent form. Br J Haematol 2004;126:410–417.

Kraat YJ, Hendrix MG, Wijnen RM, et al. Detection of latent human cytomegalovirus in organ tissue and the correlation with serological status. Transpl Int 1992;5 (Suppl 1):S613–S616.

Hendrix MG, Dormans PH, Kitslaar P, et al. The presence of cytomegalovirus nucleic acids in arterial walls of atherosclerotic and nonatherosclerotic patients. Am J Pathol 1989;134:1151–1157.

Hendrix RM, Wagenaar M, Slobbe RL, et al. Widespread presence of cytomegalovirus DNA in tissues of healthy trauma victims. J Clin Pathol 1997;50:59–63.

Kondo K, Shimada K, Sashihara J, et al. Identification of human herpesvirus 6 latency-associated transcripts. J Virol 2002;76:4145–4151.

Kondo K, Kondo T, Okuno T, et al. Latent human herpesvirus 6 infection of human monocytes/macrophages. J Gen Virol 1991;72:1401–1408.

Cuomo L, Angeloni A, Zompetta C, et al. Human herpesvirus 6 variant A, but not variant B, infects EBV-positive B lymphoid cells, activating the latent EBV genome through a BZLF-1-dependent mechanism. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 1995;11:1241–1245.

Maric I, Bryant R, Abu-Asab M, et al. HHV-6 associated acute lymphadenitis in immunocompetent adults. Mod Pathol 2004;17:1427–1433.

Luppi M, Barozzi P, Garber R, et al. Expression of human herpesvirus-6 antigens in benign and malignant lymphoproliferative diseases. Am J Pathol 1998;153:815–823.

Goodman AD, Mock DJ, Powers JM, et al. Human herpesvirus 6 genome and antigen in acute multiple sclerosis lesions. J Infect Dis 2003;187:1365–1376.

Collot S, Petit B, Bordessoule D, et al. Real-time PCR for quantification of human herpesvirus 6 DNA from lymph nodes and saliva. J Clin Microbiol 2002;40:2445–2451.

Di Luca D, Mirandola P, Ravaioli T, et al. Human herpesviruses 6 and 7 in salivary glands and shedding in saliva of healthy and human immunodeficiency virus positive individuals. J Med Virol 1995;45:462–468.

Sumiyoshi Y, Kikuchi M, Ohshima K, et al. A case of human herpesvirus-6 lymphadenitis with infectious mononucleosis-like syndrome. Pathol Int 1995;45:947–951.

Randhawa PS, Jenkins FJ, Nalesnik MA, et al. Herpesvirus 6 variant A infection after heart transplantation with giant cell transformation in bile ductular and gastroduodenal epithelium. Am J Surg Pathol 1997;21:847–853.

Knox KK, Carrigan DR . Active HHV-6 infection in the lymph nodes of HIV-infected patients: in vitro evidence that HHV-6 can break HIV latency. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 1996;11:370–378.

Kempf W, Adams V, Wey N, et al. CD68+ cells of monocyte/macrophage lineage in the environment of AIDS-associated and classic sporadic Kaposi sarcoma are singly or doubly infected with human herpesviruses 7 and 6B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997;94:7600–7605.

Kempf W, Muller B, Maurer R, et al. Increased expression of human herpesvirus 7 in lymphoid organs of AIDS patients. J Clin Virol 2000;16:193–201.

Yadav M, Nambiar S, Khoo SP, et al. Detection of human herpesvirus 7 in salivary glands. Arch Oral Biol 1997;42:559–567.

Kempf W, Adams V, Mirandola P, et al. Persistence of human herpesvirus 7 in normal tissues detected by expression of a structural antigen. J Infect Dis 1998;178:841–845.

Chen RL, Lin JC, Wang PJ, et al. Human herpesvirus 8-related childhood mononucleosis: a series of three cases. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004;23:671–674.

Diamond C, Brodie SJ, Krieger JN, et al. Human herpesvirus 8 in the prostate glands of men with Kaposi's sarcoma. J Virol 1998;72:6223–6227.

Blasig C, Zietz C, Haar B, et al. Monocytes in Kaposi's sarcoma lesions are productively infected by human herpesvirus 8. J Virol 1997;71:7963–7968.

Decker LL, Shankar P, Khan G, et al. The Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is present as an intact latent genome in KS tissue but replicates in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of KS patients. J Exp Med 1996;184:283–288.

Corbellino M, Poirel L, Bestetti G, et al. Restricted tissue distribution of extralesional Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS patients with Kaposi's sarcoma. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 1996;12:651–657.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms Judith A Smith and members of the UTMB Autopsy Division (Judith F Aronson, MD, Director) for their valuable cooperation and assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, T., Hudnall, S. Anatomical mapping of human herpesvirus reservoirs of infection. Mod Pathol 19, 726–737 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800584

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800584

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Acute myelitis with multicranial neuritis caused by Varicella zoster virus: a case report

BMC Neurology (2022)

-

Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived salivary gland organoids model SARS-CoV-2 infection and replication

Nature Cell Biology (2022)

-

Visceral disseminated varicella-zoster virus infection in an immunocompetent host

Clinical Journal of Gastroenterology (2022)

-

Frequency of varicella zoster virus DNA in human adrenal glands

Journal of NeuroVirology (2016)

-

Detection frequency of human herpesviruses-6A, -6B, and -7 genomic sequences in central nervous system DNA samples from post-mortem individuals with unspecified encephalopathy

Journal of NeuroVirology (2016)