Abstract

DeltaNp63 (DNp63) has become widely used, in particular, for distinguishing invasive carcinomas from noninvasive ducts by highlighting the myoepithelial or basal cells in the breast and prostate, respectively. It is not known whether this marker may have any application in another exocrine organ, the pancreas. As the ductal and intraductal proliferations of this organ become better characterized, the need for markers to distinguish among these processes increases. We investigated immunohistochemical expression of DNP63 in 105 cases. A total of 25 cases were non-neoplastic pancreata, 25 were pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) of various grades, and 50 were examples of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Sections of non-neoplastic pancreata included various types of non-neoplastic processes such as squamous/transitional metaplasia (five cases), which can be mistaken for high-grade PanINs, as well as various degrees of reactive ductal atypia and incidental microcysts with attenuated lining (five cases). No DNp63 expression was noted in normal pancreatic ducts. On the other hand, all five foci of squamous/transitional metaplasia were strongly and uniformly positive for this marker. DNp63 labeling was also noted in those incidental microcysts lined by attenuated cells, seen amidst normal pancreatic lobules. All PanINs were negative. Among invasive carcinomas, DNp63 expression was detected only in areas of squamous differentiation and was completely absent in ordinary ductal areas. Based on this observation, five additional cases of adenosquamous/squamous carcinoma was retrieved and stained, and the squamous components of all of these were also positive. In conclusion, (I) DNp63 is a reliable marker of squamous differentiation in the pancreas. It is valuable in distinguishing squamous/transitional metaplasia from PanINs, a distinction of importance for both researchers and diagnosticians. Among invasive carcinomas, it seems to be entirely specific for areas of squamous differentiation. (II) Those incidental microcysts seen in acinar lobules and lined by attenuated cells are also positive for DNp63, which suggests that they may be metaplastic in nature, and that they do not represent neoplastic cells. (III) Unlike the ducts of other exocrine organs, breast and prostate, there are no DNp63-expressing cells in the normal pancreatic ducts, and therefore, this marker cannot be used in distinguishing invasive carcinomas from the non-invasive ducts. (IV) No p63-expressing ‘stem’ cells are present in the pancreas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

p63 is a member of the p53 family of molecules. It has a high degree of homology with p53, but its function seems to be substantially different. Although considered a regulator of cell cycle and apoptosis like p53, p63 does not appear to be as essential as p53 itself for the cellular machinery.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 For instance, p63-null mice do not develop tumors.4, 6 The role of p63 in tumor progression or suppression seems to be far more limited.2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 While the role of p63 in cellular pathways is not well understood, it has been suggested that it is the molecular switch for initiation of the epithelial stratification program.13

Not only does the role, but the regulation of p63 also appear to be complex. Often, there is no correlation between the amplification of p63 gene and the expression levels of p63 protein.3 This is partly attributed to the various post-translational modifications that this molecule undergoes.4 Furthermore, there are various isoforms of p63,13, 14, 15 the expression of which varies significantly from tissue to tissue.15 p63 is expressed both as a multiple alternatively spliced C-terminal isoform and as N-terminally deleted, dominant-negative protein with reciprocal functional regulation.4

The isoform of p63 that is referred to as DeltaN (DNp63), which lacks the transactivation domain, is detectable immunohistochemically in the ‘stem’ cell types (basal cells and myoepithelial cells)14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 but is typically lacking in the differentiated epithelial cells except for squamous epithelium.18

DNp63 has been found to have two major applications in diagnostic pathology.

(I) As a marker of ‘stem’ (basal or myoepithelial) cells. Typically, the normal ducts of prostate and breast, unlike the invasive carcinoma glands of these organs, have a continuous peripheral layer of basal/myoepithelial cells. This specific expression of DNp63 has rendered it a highly reliable marker in the distinction of invasive carcinoma from benign ducts in these exocrine organs.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21

(II) As a marker of squamous differentiation. Another application of DNp63 in surgical pathology has been identified as its specificity for squamous differentiation. As the key molecule of the epithelial stratification program,13 DNp63 expression is highly specific for squamous differentiation in neoplasia, and is usually not detected in nonsquamous carcinomas such as adenocarcinoma, small cell carcinoma or mesothelioma and others.3, 9, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26 This is valuable in the differential diagnosis of poorly differentiated malignant tumors of undetermined origin.

The experience with p63 expression in the pancreas is limited. Ito et al27 have noted p63 gene amplification in >60% of the ductal adenocarcinomas of the pancreas; however, they have not found any correlation with clinicopathologic findings. Immunohistochemical expression of DNp63, on the other hand, as applied in other exocrine organs, has not been systematically tested in the normal pancreas or in the pathologic conditions of this organ.

Materials and methods

Immunohistochemical expression of DNp63 was tested in 105 cases. A total of 25 examples of non-neoplastic pancreatic tissue, 25 examples of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) of various grades, 50 cases of pancreatic adenocarcinoma of ductal type and five examples of adenosquamous/squamous carcinoma were identified from the files of the authors’ institutions (Harper University Hospital, Karmanos Cancer Institute and Wayne State University; VA Medical Center; Providence Hospital). The pathology material, including the surgical pathology reports, routine formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded and H&E-stained sections of all cases were reviewed.

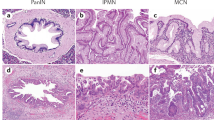

Sections of the non-neoplastic pancreata included various types of non-neoplastic processes such as squamous/transitional metaplasia (five cases; Figure 1), which can manifest as multilayered epithelium mimicking high-grade PanIN (Figure 2), and incidental microcysts (five cases; Figures 3 and 4), seen amidst normal pancreatic lobules.

In all cases, immunohistochemical stains for p63 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA; dilution 1:100; treatment Steam&EDTA) were performed. Routine streptavidin–biotin peroxidase method was used. Negative and positive controls (prostate) were included with each batch of slides tested.

Results

No DNp63 expression was noted in normal pancreatic ducts (0/25). All PanINs were negative (0/25; Figure 5). On the other hand, all five foci of squamous/transitional metaplasia showed strong and uniform nuclear positivity for this marker (5/5; Figure 6). Expression was detected in all cells of squamous nature. DNp63 labeling was also seen in five incidental microcysts (5/5). Typically these cysts had a basal layer of ovoid cells with minimal/no cytoplasm, which showed nuclear labeling with p63. There was a separate luminal layer composed of one or more cells, which were nonmucinous and flattened with transparent cytoplasm, and this was negative for p63. Pale, acidophilic concentrations, typical of acinar secretions, were present in the lumen of these cysts (Figure 7). However, the lining cells did not show morphologic features of acinar cells (devoid of any intracytoplasmic granules and no prominent nucleoli present).

Among 50 invasive ductal carcinomas, DNp63 expression was detected only in areas of squamous differentiation (two cases, Figure 8). Ordinary tubular and poorly differentiated nonsquamous components of these two cases were completely negative. DNp63 was completely absent in ordinary ductal areas (0/48). In addition, the squamous components of all of adenosquamous/squamous carcinoma cases were also strongly positive (5/5).

The results are shown in Table 1.

Discussion

DNp63 is valuable in distinguishing intraductal squamous metaplasia from intraductal neoplasia, because it is consistently expressed in squamous/transitional metaplasia in pancreatic ducts, but typically absent in the PanIN. Transitional/squamous metaplasia typically manifests as multilayered epithelium with some degrees of disorganization, and may therefore mimic high-grade PanINs. PanIN diagnosis is important. Whereas low-grade PanINs are common incidental findings, high-grade PanINs are typically associated with ductal adenocarcinoma.28 Furthermore, high-grade PanINs may have potential for progressing into invasive carcinoma and therefore should duly be reported in the surgical pathology report in a patient with no other neoplasia.29, 30 Therefore, the distinction of PanINs from squamous metaplasia is important, not only for researchers but also for diagnosticians. At the same time, this differential expression of DNp63 raises the interesting question of whether the progression of PanIN can be turned off by induction of p63. As a proapoptotic molecule,15 a homologue of p53, and as the molecule that triggers epithelial stratification,13 p63 is likely to be responsible for squamous transformation of the ductal epithelial cells. Therefore, it is conceivable that activation (or induction) of p63 may divert the intraductal neoplastic cells towards a more mature, metaplastic process.

As in other organs,3, 9, 23, 24, 25 DNp63 is a reliable marker of squamous differentiation also in pancreatic carcinoma. Among invasive carcinomas of the pancreas, DNp63 immuno-expression is largely limited to the areas of squamous differentiation. Ordinary ductal adenocarcinomas, including the poorly differentiated components, are typically negative for this marker. DNp63 may be useful in distinguishing poorly differentiated pancreatic carcinomas from poorly differentiated squamous carcinomas of especially pulmonary origin. Occasionally, this differentiation is important in determining the primary source of metastatic carcinomas, both in the liver and in the pancreas itself. Pulmonary and pancreatic carcinomas are two of the most common primaries that metastasize to the liver,31 and they are also the most common sources of ‘carcinoma of unknown origin’.32, 33 Furthermore, lung cancer is the most common tumor to metastasize to the pancreas.34 Therefore, on occasion this differentiation becomes an important issue and p63 can be successfully utilized in this distinction.

DNp63 is not helpful in the separation of ductal adenocarcinoma from normal ducts. Unlike in the other exocrine organs prostate and breast,14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 immunohistochemical expression of DNp63 is not applicable in the pancreas to distinguish normal ducts from invasive carcinoma. In fact, the lack of DNp63 labeling in this study confirms the absence of a basal/myoepithelial cell layer in this organ.

This study also confirms our previous finding that there are no identifiable stem cells residing within the pancreatic ducts.35 Some authors believe that pancreatic ducts contain stem cells,36 which are presumed to be the counterparts of ‘oval’ cells in the liver (Carolyn C Compton, September 1999, personal communications).37 There are indeed rare, scattered nonductal cells within the ductal epithelium. These were originally identified by Feyrter,38 who referred to them as ‘helle Zellen’. In our experience,35 these cells usually prove to be endocrine in nature by immunohistochemistry and they probably do not represent stem cells. In this study, these cells have failed to label with DNp63, which is reported as a ‘stem cell marker’ by some authors,14, 22 hence bringing further doubt to the ‘stem’ cell nature of these cells.

This study has also shown that those incidental microcysts within normal pancreatic parenchyma, which generally measure no more than 2–3 mm, are metaplastic in nature. They are typically lined by attenuated cells that cytologically resemble centroacinar cells (neither ductal nor acinar in morphology), and they contain amorphous acidophilic muco-secretory plugs characteristic of enzymatic concretions, suggesting that these cysts actively communicate with the acini, and may represent dilatation of the centroacinar system. For this reason, we have been referring to these cysts as ‘centroacinar microcyst’. The nature of these microcysts, which are relatively common incidental findings, has been difficult to determine. It is also difficult to determine whether they are related to the recently described acinar cell cystadenoma.39 In this study, these microcysts were consistently positive for DNp63 in contrast to the rest of the pancreatic parenchyma. This suggests that the cells lining these cysts, especially those that are basally located, had undergone squamous transformation, that is, a metaplastic process.

In conclusion, DNp63 expression in the pancreas appears to be limited to squamous differentiation and may aid in distinguishing squamous/transitional metaplasia from PanINs. It is also a marker for squamous differentiation in invasive carcinoma. Unlike the breast or prostate, there are no DNp63-expressing basal/myoepithelial cells in the pancreas; therefore, this marker is not applicable in the distinction of invasive carcinoma from benign ducts.

References

Choi HR, Batsakis JG, Zhan F, et al. Differential expression of p53 gene family members p63 and p73 in head and neck squamous tumorigenesis. Hum Pathol 2002;33:158–164.

Urist MJ, Di Como CJ, Lu ML, et al. Loss of p63 expression is associated with tumor progression in bladder cancer. Am J Pathol 2002;161:1199–1206.

Geddert H, Kiel S, Heep HJ, et al. The role of p63 and deltaNp63 (p40) protein expression and gene amplification in esophageal carcinogenesis. Hum Pathol 2003;34:850–856.

Melino G, Lu X, Gasco M, et al. Functional regulation of p73 and p63: development and cancer. Trends Biochem Sci 2003;28:663–670.

Chen YK, Huse SS, Lin LM . Differential expression of p53, p63 and p73 protein and mRNA for DMBA-induced hamster buccal-pouch squamous-cell carcinomas. Int J Exp Pathol 2004;85:97–104.

Parsons JK, Gage WR, Nelson WG, et al. p63 protein expression is rare in prostate adenocarcinoma: implications for cancer diagnosis and carcinogenesis. Urology 2001;58:619–624.

Irwin MS, Kaelin Jr WG . Role of the newer p53 family proteins in malignancy. Apoptosis 2001;6:17–29.

Koga F, Kawakami S, Fujii Y, et al. Impaired p63 expression associates with poor prognosis and uroplakin III expression in invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Clin Cancer Res 2003;9:5501–5507.

Massion PP, Taflan PM, Jamshedur Rahman SM, et al. Significance of p63 amplification and overexpression in lung cancer development and prognosis. Cancer Res 2003;63:7113–7121.

Moll UM . The role of p63 and p73 in tumor formation and progression: coming of age toward clinical usefulness. Clin Cancer Res 2003;9:5437–5441.

Puig P, Capodieci P, Drobnjak M, et al. p73 expression in human normal and tumor tissues: loss of p73alpha expression is associated with tumor progression in bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2003;9:5642–5651.

Douc-Rasy S, Goldschneider D, Million K, et al. Interrelations between p73 and p53: a model, neuroblastoma. Med Sci (Paris) 2004;20:317–324.

Koster MI, Kim S, Mills AA, et al. p63 is the molecular switch for initiation of an epithelial stratification program. Genes Dev 2004;18:126–131.

Reis-Filho JS, Schmitt FC . Taking advantage of basic research: p63 is a reliable myoepithelial and stem cell marker. Adv Anat Pathol 2002;9:280–289.

Vincek V, Knowles J, Li J, et al. Expression of p63 mRNA isoforms in normal human tissue. Anticancer Res 2003;23:3945–3948.

Davis LD, Zhang W, Merseburger A, et al. p63 expression profile in normal and malignant prostate epithelial cells. Anticancer Res 2002;22:3819–3825.

Weinstein MH, Signoretti S, Loda M . Diagnostic utility of immunohistochemical staining for p63, a sensitive marker of prostatic basal cells. Mod Pathol 2002;15:1302–1308.

Werling RW, Hwang H, Yaziji H, et al. Immunohistochemical distinction of invasive from noninvasive breast lesions: a comparative study of p63 versus calponin and smooth muscle myosin heavy chain. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:82–90.

Zhou M, Shah R, Shen R, et al. Basal cell cocktail (34betaE12 + p63) improves the detection of prostate basal cells. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:365–371.

Stefanou D, Batistatou A, Nonni A, et al. p63 expression in benign and malignant breast lesions. Histol Histopathol 2004;19:465–471.

Westfall MD, Pietenpol JA . p63: molecular complexity in development and cancer. Carcinogenesis 2004;25:857–864.

Reis-Filho JS, Preto A, Soares P, et al. p63 expression in solid cell nests of the thyroid: further evidence for a stem cell origin. Mod Pathol 2003;16:43–48.

Hu H, Xia SH, Li AD, et al. Elevated expression of p63 protein in human esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Cancer 2002;102:580–583.

Pelosi G, Pasini F, Olsen Stenholm C, et al. p63 immunoreactivity in lung cancer: yet another player in the development of squamous cell carcinomas? J Pathol 2002;198:100–109.

Wu M, Wang B, Gil J, et al. p63 and TTF-1 immunostaining. A useful marker panel for distinguishing small cell carcinoma of lung from poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of lung. Am J Clin Pathol 2003;119:696–702.

Foschini MP, Gaiba A, Cocchi R, et al. Pattern of p63 expression in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Virchows Arch 2004;444:332–339.

Ito Y, Takeda T, Wakasa K, et al. Expression of p73 and p63 proteins in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: p73 overexpression is inversely correlated with biological aggressiveness. Int J Mol Med 2001;8:67–71.

Andea A, Sarkar F, Adsay VN . Clinicopathological correlates of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia: a comparative analysis of 82 cases with and 152 cases without pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol 2003;16:996–1006.

Brat DJ, Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ, et al. Progression of pancreatic intraductal neoplasias to infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22:163–169.

Hruban RH, Adsay NV, Albores-Saavedra J, et al. Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia: a new nomenclature and classification system for pancreatic duct lesions. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:579–586.

Rosai J . Liver tumors and tumorlike conditions. In: Rosai and Ackerman's Surgical Pathology, 9th edn. Mosby, New York, NY, 2004. p 1015.

Greco FA, Hainsworth JD . Tumors of unknown origin. CA Cancer J Clin 1992;42:96–115.

Pavlidis N, Briasoulis E, Hainsworth J, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic management of cancer of an unknown primary. Eur J Cancer 2003;39:1990–2005.

Adsay NV, Andea A, Basturk O, et al. Secondary tumors of the pancreas: an analysis of a surgical and autopsy database and review of the literature. Virchows Arch 2004;444:527–535.

Vyas P, Andea A, Sarkar F, et al. In search of a stem cell in pancreatic ducts: the nature of round, non-ductal appearing cells in human pancreatic ducts. Mod Pathol 2003;16:287A.

Pour P . Experimental pancreatic ductal (ductular) tumors. Monogr Pathol 1980;21:111–139.

Yoon BI, Choi YK, Kim DY . Differentiation processes of oval cells into hepatocytes: proposals based on morphological and phenotypical traits in carcinogen-treated hamster liver. J Comp Pathol 2004;131:1–9.

Feyrter F . The insular organ and its autonomic innervation. Acta Neuroveg (Wien) 1954;9:44–46.

Zamboni G, Terris B, Scarpa A, et al. Acinar cell cystadenoma of the pancreas: a new entity? Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:698–704.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute Specialized Program for Research Excellence (SPORE), PAR-02-068.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This study was presented in part at the annual meeting of the United States and Canadian Division of the International Academy of Pathology in Vancouver, March 2004.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Basturk, O., Khanani, F., Sarkar, F. et al. DeltaNp63 expression in pancreas and pancreatic neoplasia. Mod Pathol 18, 1193–1198 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800401

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800401

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Research advances and treatment perspectives of pancreatic adenosquamous carcinoma

Cellular Oncology (2023)

-

Morphological and p40 immunohistochemical analysis of squamous differentiation in endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle biopsies of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Overexpression and ratio disruption of ΔNp63 and TAp63 isoform equilibrium in endometrial adenocarcinoma: correlation with obesity, menopause, and grade I/II tumors

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2012)

-

Adenosquamous carcinoma of the pancreas harbors KRAS2, DPC4 and TP53 molecular alterations similar to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

Modern Pathology (2009)