Abstract

Cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (FCL) is reported to have a unique immunophenotype and clinical course as compared with nodal FCL. We studied 19 cases of FCL of the skin using paraffin embedded tissue. An immunohistochemistry panel included CD45, CD3, CD20, CD43, CD21, bcl-2, bcl-6, CD5, and CD10. Molecular studies were performed by polymerase chain reaction for immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) and t(14;18). Trisomy 3 was performed by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) in 13 cases. Follow up was obtained in 17 cases (range 3 to 137 months). Patients included 10 females and 9 males ranging in age from 33 to 88 years at first presentation (mean, 64). Twelve of 19 presented in the head and neck and 6 in the trunk and 1 on the arm. All had no known lymph node disease at presentation. Seventeen patients had no nodal disease with a minimum 3 month follow-up; 2/19 had unknown lymph node status with no follow-up. All cases were immunoreactive with CD20 and negative with CD3. Bcl-2 was immunoreactive in 11/18 cases, bcl-6 in 15/15, CD10 in 14/17, CD43 in 2/16 (both were CD10 immunoreactive) and CD5 in 1/15 (it was also bcl-6 immunoreactive). Eight of 18 cases were monoclonal for IgH. Three of 17 showed the presence of t(14;18). FISH was positive in 4 cases for trisomy 3 ranging from 16 to 22% (12% threshold). Follow-up showed no evidence of disease in 14/17 patients (4 to 137 mos). 3/17 patients are alive with disease (17 to 100 mo), and no patients died of disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The skin is the second most common site for extranodal lymphomas, after the gastrointestinal tract (1). Although follicle center lymphoma (FCL) most often occurs in lymph nodes, it may also present in the skin as both a primary or secondary manifestation of disease and is the most common B-cell lymphoma of the skin (2, 3). A lymphoma is considered to be “primary” to the skin if there is no extra-cutaneous disease at the time (and within the first 6 months) of its diagnosis (2, 4, 5). Primary cutaneous FCL has been reported in the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) for Cutaneous Lymphomas (2) and in other studies as a distinct entity, which has a good prognosis and rarely disseminates to extra-cutaneous sites (4, 6, 7). But it has been argued, that the entity classified as cutaneous FCL in the EORTC is not the same as those described in other classifications (5, 8). It is uncertain if the World Health Organization Classification of Neoplastic Diseases of Lymphoid Tissues (WHO) will consider the entity distinct, although in one proposed schema it has been proposed as a separate entity (9). Other suggestions have included cutaneous FCL as a variant of FCL (10). The Revised European-American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms (R.E.A.L.) does not recognize cutaneous FCL as a distinct entity but includes it in the broader classification of FCL (11). Sander et al. (12, 13) have proposed that the R.E.A.L. be used for cutaneous FCL but state that cutaneous FCL appears to be distinctive. Because the R.E.A.L. is the most current classification used in the United States by hematopathologists, is adequate for diagnosing cutaneous lymphomas, and the grading of FCL in this classification is well established, we classified our cases according to the R.E.A.L. classification. Using the R.E.A.L. classification is also in line with the proposed view that organ specific classifications are not necessary for recognition of common features of lymphoma involving multiple sites (13, 14). In our study, we investigated the clinical, histologic, immunophenotypic and molecular genetic features of cutaneous follicle center lymphomas. We included CD10 (15, 16), bcl-6 (marker of follicle center cells) (17), bcl-2 (18), t (14;18) (19), and trisomy 3 (20) in an attempt to better characterize cutaneous follicle center lymphomas and to separate them from other small B-cell lymphomas that can appear follicular (21).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case Selection

Nineteen cases diagnosed as cutaneous “follicular,” “follicle center,” or “nodular” lymphoma without extra-cutaneous involvement were selected from the files of the Dermatopathology Registry at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology from 1990 to 1997. There were hematoxylin-eosin stained slides and paraffin blocks (or unstained slides) in all cases. All tissues were formalin fixed. Nine cases had more than one biopsy performed. Follow- up was obtained in 17 cases. All cases were classified and graded according to the Revised European-American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms (11).

Immunohistochemistry

The immunohistochemical antibodies are shown in Table 1. Five micron sections from paraffin embedded tissue blocks were prepared for immunophenotypic analysis according to the standard avidin-biotin complex method of Hsu et al. (22). A complete antibody panel for CD45RB, CD20, CD3, CD5, CD43, CD10, bcl-6 and bcl-2 was performed in 14/19 cases in at least one specimen if more than one was available. A partial panel was performed in 5/19, based on availability of material. Cyclin D1 (bcl-1) was performed in two cases, one CD5 positive and one with equivocal CD5 reactivity.

Molecular Diagnostic Studies

Molecular diagnostic studies were performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue in 18/19 cases in at least one biopsy if multiple biopsies were available. Studies included immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH), T-cell receptor (TCR) β, and t (14;18) to detect the major breakpoint region.

IgH gene rearrangement was detected by a PCR method using published consensus primers (FR3A, V region and CFW1 J region) (23). TCR β was detected by a PCR published PCR method using four sets of primer pairs (VJ1, VJ2 D1J2, D2J2) as previously published (23). TCRβ has been described in B-cell lymphoma it therefore would not preclude the diagnosis of a B-cell lymphoma but may indicate malignancy (24). The major breakpoint region of t(14;18) was detected by primers (CH18-515) and probes (pMBR) that have been previously published (25). Her2/neu was used as a control to test for DNA integrity.

Fluorescent In situ Hybridization for Trisomy 3

The trisomy 3 assay was performed in 13/19 cases. A deparaffinization kit was used according to the manufacturer's instructions (Vysis Inc, Dowers Grove, IL.) for trisomy 3 analysis. The DNA probes for chromosome 3, region 3p11.1-q11.1 (Vysis) and chromosome 16, region 16q11.2 (Vysis) were labeled and analyzed using the manufacturer's procedure for CEP Chromosome Enumeration DNA FISH Probes (Vysis). The in situ signals were demonstrated by fluorescence microscopy. Signals were analyzed for the percentage of cells with 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 signals. Twelve percent or higher for three signals were considered positive for trisomy 3. The slides were counterstained with DAPI II counterstain (Vysis). Chromosome 16 was used as a control. The assays were performed in triplicate. Twelve percent was used as a cutoff for the lower limit of normal. We used the following to arrive at 12% as a reasonable cutoff: the manufacturer's recommendation of 10 to 11% and previously published data showing that marginal zone lymphomas have a mean of 16 to 46% positivity for trisomy 3 by FISH with 7 to 15% as the lower level of positivity for marginal zone lymphoma (20, 26, 27, 28).

RESULTS

Clinical Features

The clinical results are summarized in Table 2. There was a near equal distribution of males (9) and females (10) with ages ranging from 33 to 88 years (mean, 64 years). All of the 19 patients presented with cutaneous lesions with no other sites of involvement. Sites of disease included head and neck (12/19) and back or trunk (6/19) and arm (1/19). In 2 patients, no clinical staging history was available after the initial biopsy.

Histology

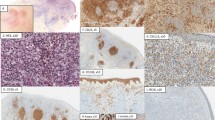

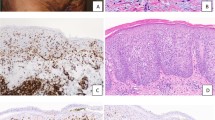

All cases showed a nodular or vaguely nodular, dense atypical lymphoid infiltrate in the deep dermis. There was a grenz zone, or sparing of the epidermis, in 18/18 cases. (In one case, the epidermis was not present for examination). Four of 19 cases were Grade I/III (small cell), 5/19 were Grade II/III (mixed small and large cell) and 8/19 were Grade III/III (large cell), 2/19 had a first biopsy graded as II/III (mixed small and large cell) and a second biopsy graded as III/III (large cell). The mantle zones were well preserved in 4/19, attenuated in 9/19 and absent in 6/19. One case (case 4) showed minimal marginal zone differentiation. In all cases there were intervening centrocytes mixed with the centroblasts with the exception of one case comprised of exclusively centroblasts. In one other case (case 15), the nodules were predominately composed of centrocytes without intervening centroblasts. Tingible body macrophages were seen in only one case. All cases lacked polarity of the malignant follicles (Fig. 1).

Immunohistochemistry

The morphologic, immunohistochemical and molecular genetic results are shown in Table 3. All cases were reactive with CD20 and negative with CD3. Bcl-2 was reactive in 11/18 cases. Bcl-6 was immunoreactive in 15/15 cases. CD10 was immunoreactive in 14/17. CD43 was immunoreactive in 2/16 cases. Both of the CD43 immunoreactive cases were also CD10 and bcl-6 immunoreactive. One of 17 cases were immunoreactive for CD5 and one case was equivocal; the CD5 immunoreactive case was bcl-6 positive and CD10 negative; both were negative with bcl-1. Eleven of 13 cases showed an organized dendritic network in the malignant nodules with CD21.

Molecular Genetic Studies

Eight of 18 cases studied showed monoclonal bands for immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) (one case was non-amplifiable and 9 were negative). Three of 17 showed the presence of t(14;18), cases 2, 5 and 10 (one case was technically unsatisfactory and one had no tissue to perform the assay). One case showed both monoclonal IgH and t(14;18). All negative cases for t(14;18) showed satisfactory DNA integrity with Her2 neu. When TCR testing was performed it is indicated in Table 3. One specimen showed TCRβ monoclonality but also showed t(14;18).

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

The immunohistochemical, molecular and FISH results are summarized in Table 3. Four of 13 cases tested showed the presence of trisomy 3 above the threshold. Of the 4 cases with trisomy 3, none showed the presence of t(14;18). Two of the 4 cases with trisomy 3 showed immunoreactivity with bcl-6 and CD10, which strongly supports follicle center origin (and not extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma). One showed immunoreactivity with bcl-6 but was negative with CD10. The remaining case was only examined with molecular studies and did not show t(14;18) or IgH rearrangements. Case 9 is shown in Figure 2 and was interpreted as positive for trisomy 3 (16%). No cases were positive for trisomy 16, a control marker.

Follow-Up

Overall, 14 of 17 patients are alive with no evidence of disease (ANED) from 4 to 137 months. Three of 17 are alive with disease (AWD) from 17 to 100 months. No follow- up information could be obtained in 2 cases. When examined by cytologic subtypes, follow-up shows that of patients with Grade I/III, 4/4 were ANED. Of the patients with FCL Grade II/III, 2/4 were ANED, 2/4 were AWD and in 1/4 no FU was obtained. Of patients with Grade III/III disease, 6/8 were ANED, 1/8 AWD, and in 1/8 no FU could be obtained. Two patients had 2 biopsies the first showing Grade II/III and the second showing Grade III/III. One of these patients was AWD and the other ANED.

DISCUSSION

Cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is considered by the EORTC classification to be a distinct clinicopathologic entity from nodal FCL. The R.E.A.L. does not recognize cutaneous FCL as a separate entity but considers it to be an extranodal presentation of FCL. The R.E.A.L. does not address the specific clinical behavior of cutaneous FCL but includes it within the broader FCL, which is “generally indolent” (11). The EORTC classification indicates that cutaneous FCL has indolent clinical behavior with a 5-year survival of 97%. It occurs most often in the head and neck region with only rare dissemination to extra-cutaneous sites and does not appear to have shorter survival with higher-grade lesions (2, 23). In contrast, the reported overall 5-year survival of nodal FCL is 67%, although higher grade FCL (follicular large cell versus follicular small cell) offered worse survival (29). But there are exceptions, with occasional cases of nodal FCL having long survival with little or no treatment even in those cases having large cell morphology (30). Our findings support the reported indolent clinical behavior and show no correlation in survival with grading of the lymphoma.

Survival in noncutaneous FCL also has been reported to have worse prognosis when bcl-2 rearrangements are absent, a finding not typically seen in cutaneous FCL (31). We report a low level of t(14;18) positivity in our cases by PCR (3/17 or 18%). This low percentage of t(14;18) may be inherent in the PCR method from paraffin embedded tissue, rather than a true lack of t(14;18) because there have been similar low levels of t(14;18) in previously reported findings in nodal FCL of 20 to 50% in paraffin embedded tissues (32, 33, 34, 35). In contrast to our study, a recent study reported no cases of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma possessed the t(14;18) (4). Although we feel that our findings reflect true presence of t(14;18), even in the present study, the rate of t(14;18) in cutaneous FCL is much less than nodal FCL, which in our laboratory is approximately 40% using PCR from paraffin tissue. Bcl-2 protein expression does not appear to reflect the incidence of t(14;18). However, bcl-2 protein expression was higher in the present study, than that previously reported in which bcl-2 was positive in only 0 to 46% (4, 33, 36, 37, 38). This also includes the EORTC, which notes that follicular lymphomas rarely express bcl-2 (2). A recent study found 3 of 4 cases showed immunoreactivity for bcl-2 but these cases were secondary (39). Because bcl-2 has been reported in a variety of small B-cell lymphomas without t(14;18) it is less specific than once thought in FCL, both cutaneous and in lymph node.

Bcl-6 and CD10 are both markers of follicle center cells and are immunoreactive in noncutaneous follicle center lymphomas (16, 40, 41). Our study shows they are also immunoreactive in the cutaneous form of FCL. Previous reports are not consistent in their finding of CD10 immunoreactivity. Reports by Willemze et al. (2), Berti et al. (42), and Santucci et al. (43) show no CD10 immunoreactivity, although a report by Garcia et al. did show cases that were immunoreactive with CD10 (44), and Yang et al. showed 14/15 cases immunoreactive (33). CD10 immunoreactivity is in keeping with Norton's (8) view that the true FCL of the skin have a similar immunophenotype to nodal FCL. Bcl-6 is a recently recognized germinal center cell marker (40), which has been reported positive in 15/15 cutaneous FCL in one previous study by Yang et al. (33). We found these two markers particularly helpful in differentiating FCL from both mantle cell lymphoma and marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, which support previous reported findings in nodal disease (17). We also found that CD21 highlighted the organized follicular dendritic cells in the malignant nodules, particularly in the lower grades, and was also helpful; a finding similar to that in nodal FCL (11). These findings also are supportive of the view that an organ specific classification such as the EORTC is not required and indeed may impede the recognition of common features of lymphomas involving multiple anatomic sites (13, 14).

The significance of CD5 or CD43 immunoreactivity in cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is unknown, but our study suggests that this co-expression with CD10 does not adversely affect clinical outcome. The low expression of CD43 in our study is consistent with previous reports of rare cases of FCL (45, 46). The two CD43 immunoreactive cases in this study are Grade III. Lai et al. also reported Grade III FCL expressing CD43 more often than Grade I or II (45). The coexpression of CD5 and CD10 has also been reported other small B-cell lymphomas (47) and in a recent report by Tiesinga et al. describing a unique floral variant of FCL (48). We do not know the significance of the CD5 expression in this study.

The percentage of cells determined with FISH to be positive for trisomy 3 (above the 12% threshold) in our study is 16 to 22% (mean 19%) and is in the scope of previously reported mean values in marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract (16 to 46%). Of note, the actual number of positive cells in previous reports varied greatly (7.5 to 86%) (20, 26, 27, 28). Blanco et al. and Wotherspoon et al. also examined other types of lymphoma and found low levels of trisomy three (20, 26). Our findings likely represent a true low level of trisomy 3, similar to previous reports in which +3 and +3p have been found in FCL in lymph node (49, 50). When seen in nodal FCL it is generally in Grade II or III, which may or may not also have the t(14;18) (49, 50, 51). Trisomy 3 in high-grade lymphoma may impart a good prognosis (49). None of our cases with trisomy 3 has marginal zone differentiation (marginal zone differentiation was minimally present in only one of our cases of FCL without trisomy 3); therefore it is not a likely explanation for the trisomy 3 positivity by FISH. Cytogenetics performed on fresh tissue, which is not available to us, would be helpful in further characterizing this finding.

The findings in this study highlight the morphologic and immunophenotypic and genotypic features of cutaneous FCL. Previous studies of cutaneous FCL may have included other small B-cell lymphomas with a nodular appearance making it difficult to “sort out” the reported findings. With the new paraffin markers available, it is more likely that cutaneous follicle center lymphoma will become a better-defined entity. Cutaneous FCL, it appears, has an immunophenotype similar to that of nodal FCL, although it may act in a more indolent manner, but this remains to be substantiated. Continuing study is necessary to completely characterize this neoplasm.

References

Freeman C, Berg JW, Cutler SJ . Occurrence and prognosis of extranodal lymphomas. Cancer 1972; 29: 252–260.

Willemze R, Kerl H, Sterry W, Berti E, Cerroni L, Chimenti S, et al. EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas: a proposal from the Cutaneous Lymphoma Study Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Blood 1997; 90: 354–371.

Gilliam AC, Wood GS . Primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides. Semin Oncol 1999; 26: 290–306.

Cerroni L, Arzberger E, Putz B, Hofler G, Metze D, Sander CA, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center cell lymphoma with follicular growth pattern. Blood 2000; 95: 3922–3928.

Willemze R, Meijer CJ . EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas: the best guide to good clinical management. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Am J Dermatopathol 1999; 21: 265–273.

Kerl H, Kresbach H . Germinal center cell-derived lymphomas of the skin. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1984; 10: 291–295.

Pimpinelli N, Santucci M, Bosi A, Moretti S, Vallecchi C, Messori A, et al. Primary cutaneous follicular centre-cell lymphoma- a lymphoproliferative disease with favourable prognosis. Clin Exp Dermatol 1989; 14: 12–19.

Norton AJ . Classification of cutaneous lymphoma: a critical appraisal of recent proposals. Am J Dermatopathol 1999; 21: 279–287.

Jaffe ES . Hematopathology: integration of morphologic features and biologic markers for diagnosis. Mod Pathol 1999; 12: 109–115.

Chan JKC . Is the REAL classification for REAL? Do we need a separate classification for cutaneous lymphomas? Adv Anat Pathol 1997; 4: 359–369.

Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein J, Banks PM, Chan JKC, Cleary ML, et al. A revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 1994; 84: 1361–1392.

Sander CA, Kind P, Kaudewitz P, Raffeld M, Jaffe ES . The Revised European-American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms (REAL): a new perspective for the classification of cutaneous lymphomas. J Cutan Pathol 1997; 24: 329–341.

Sander CA, Flaig MJ, Kaudewitz P, Jaffe ES . The revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms (REAL): a preferred approach for the classification of cutaneous lymphomas. Am J Dermatopathol 1999; 21: 274–278.

Jaffe ES, Sander CA, Flaig MJ . Cutaneous lymphomas: a proposal for a unified approach to classification using the R.E.A.L./WHO classification. Ann Oncol 2000; 11 (Suppl 1): S17–S21.

Almasri NM, Iturraspe JA, Braylan RC . CD10 expression in follicular lymphoma and large cell lymphoma is different from that of reactive lymph node follicles. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1998; 122: 539–544.

McIntosh GG, Lodge AJ, Watson P, Hall AG, Wood K, Anderson JJ, et al. NCL-CD10–270: a new monoclonal antibody recognizing CD10 paraffin-embedded tissue. Am J Pathol 1999; 154: 77–82.

Raible MD, Hsi ED, Alkan S . Bcl-6 protein expression by follicle center lymphomas. A marker for differentiating follicle center lymphoma from other low-grade lymphoproliferative disorders. Am J Clin Pathol 1999; 112: 101–107.

Lai R, Arber DA, Chang KL, Wilson CS, Weiss LM . Frequency of bcl-2 expression in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a study of 778 cases with comparison of marginal zone lymphoma and monocytoid B-cell hyperplasia. Mod Pathol 1998; 11: 864–869.

Crisan D, Anstett MJ . bcl-2 gene rearrangements in follicular lymphomas. Lab Med 1993; 24: 579–588.

Wotherspoon AC, Finn TM, Isaacson PG . Trisomy 3 in low-grade B-cell lymphomas of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Blood 1995; 85: 2000–2004.

Isaacson PG . Malignant lymphomas with a follicular growth pattern. Histopathology 1996; 28: 487–495.

Hsu S-MRLFH . Use of avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) in immunoperoxidase techniques: a comparison between ABC and unlabeled antibody (PAP) procedures. J Histochem Cytochem 1981; 29: 577–580.

Abruzzo LV, Griffith LM, Nandedkar M, Aguilera NS, Taubenberger JK, Raffeld M, et al. Histologically discordant lymphomas with B-cell and T-cell components. Am J Clin Pathol 1997; 108: 316–323.

Krafft AE, Taubenberger JK, Sheng ZM, Bijwaard KE, Abbondanzo SL, Aguilera NSI, et al. Enhanced sensitivity with a novel TCRgamma PCR assay for clonality studies in 569 formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) cases. Mol Diagn 1999; 4: 119–133.

Abbondanzo SL, Rush W, Bijwaard KE, Koss MN . Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the lung: a clinicopathologic study of 14 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24: 587–597.

Blanco R, Lyda M, Davis B, Kraus M, Fenoglio-Preiser C . Trisomy 3 in gastric lymphomas of extranodal marginal zone B-cell (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue) origin demonstrated by FISH in intact paraffin tissue sections. Hum Pathol 1999; 30: 706–711.

Dierlamm J, Michaux L, Wlodarska J, Pittaluga S, Zeller W, Stul M, et al. Trisomy 3 in marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: a study based on cytogenetic analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization. Br J Hematol 1996; 93: 242–249.

Zhang Y, Cheung ANY, Chan ACL, Shen D-H, Xu W-S, Chung L-P, et al. Detection of trisomy 3 in primary gastric B-cell lymphoma by using in situ hybridization on paraffin sections. Am J Clin Pathol 1998; 110: 347–353.

Martin AR, Weisenberger Chan WC, Ruby EI, Anderson JR, Vose JM, et al. Prognostic value of cellular proliferation and histologic grade in follicular lymphoma. Blood 1995; 85: 3671–3678.

Sapunar F, Catovsky D, Wotherspoon A, Matutes E . Follicular lymphoma. A series of 11 patients with minimal or no treatment and long survival. Leuk Lymphoma 2000; 37: 163–167.

Lopez-Guillermo A, Cabanillas F, McDonnell TI, McLaughlin P, Smith T, Pugh W, et al. Correlation of bcl-2 rearrangement with clinical characteristics and outcome in indolent follicular lymphoma. Blood 1999; 93: 3081–3087.

Liu J, Johnson RM, Traweek ST . Rearrangement of the BCL-2 gene in follicular lymphoma. Detection by PCR in both fresh and fixed tissue samples. Diagn Mol Pathol 1993; 2: 241–247.

Yang B, Tubbs RR, Finn W, Carlson A, Pettay J, Hsi ED . Clinicopathologic reassessment of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas with immunophenotypic and molecular genetic characterization. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24: 694–702.

Miettinen M, Lasota J . Polymerase chain reaction based gene rearrangement studies in the diagnosis of follicular lymphoma-performance in formaldehyde-fixed tissue and application in clinical problem cases. Pathol Res Pract 1997; 193: 9–19.

Shibata D, Hu E, Weiss LM, Brynes RK, Nathwani BN . Detection of specific t(14;18) chromosomal translocations in fixed tissues. Hum Pathol 1990; 21: 199–203.

Cerroni L, Volkenandt M, Rieger E, Soyer P, Kerl H . bcl-2 protein expression and correlation with the interchromosomal 14;18 translocation in cutaneous lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. J Invest Dermatol 1994; 102: 231–235.

Chimenti S, Cerroni L, Zenahlik P, Peris K, Kerl H . The role of MT2 and anti-bcl-2 protein antibodies in the differentiation of benign from malignant cutaneous infiltrates of B-lymphocytes with germinal center formation. J Cutan Pathol 1996; 23: 319–322.

Geelen FAMJ, Vermeer MH, Meijer CJLM, Van der Putte SCJ, Kerhof E, Kluin PM, et al. Bcl-2 protein expression in primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma is site-related. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 2080–2085.

Triscott JA, Ritter JH, Swanson PE, Wick MR . Immunoreactivity for bcl-2 protein in cutaneous lymphomas and lymphoid hyperplasias. J Cutan Pathol 1995; 22: 2–10.

Falini B, Fizzotti M, Pileri S, Liso A, Pasqualucci L, Flenghi L . Bcl-6 protein expression in normal and neoplastic lymphoid tissues. Ann Oncol 1997; 8 (Suppl 2): 101–104.

Kaufmann O, Flath B, Spath-Schwalbe E, Possinger K, Dietel M . Immunohistochemical detection of CD10 with monoclonal antibody 56C6 on paraffin sections. Am J Clin Pathol 1999; 111: 117–122.

Berti EAE, Caputo R . Reticulohistiocytoma of the dorsum (Crosti's disease) and other B-cell lymphomas. Semin Diag Pathol 1991; 8: 82–90.

Santucci M, Pimpinelli N, Arganini L . Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: a unique type of low-grade lymphoma. Clinicopathologic and immunologic study of 83 cases. Cancer 1991; 67: 2311–2326.

Garcia CF, Weiss LM, Warnke RA, Wood GS . Cutaneous follicular lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1986; 10: 454–463.

Lai R, Weiss LM, Chang KL, Arber DA . Frequency of CD43 expression in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. A survey of 742 cases and further characterization of rare CD43+ follicular lymphomas. Am J Clin Pathol 1999; 111: 488–494.

Treasure J, Lane A, Jones DB, Wright DH . CD43 expression in B cell lymphoma. J Clin Pathol 1992; 45: 1018–1022.

Bookman MA, Lardelli P, Jaffe ES, Duffey PL, Longo DL . Lymphocytic lymphoma of intermediate differentiation: morphologic, immunophenotypic, and prognostic factors. J Natl Cancer Inst 1990; 82: 742–748.

Tiesinga JJ, Wu CD, Inghirami G . CD5+ follicle center lymphoma. Immunophenotyping detects a unique subset of “floral” follicular lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol 2000; 114: 912–921.

Schouten HC, Sanger WG, Weinsinberger DD, Anderson J, Armitage JO, for the Nebraska Lymphoma Study Group. Chromosomal abnormalities in untreated patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: associations with histology, clinical characteristics and treatment outcome. Blood 1990; 75: 1841–1847.

Yunis JJ, Frizzera G, Oken MM, McKenna J, Theologides A, Arnesen M . Multiple recurrent genomic defects in follicular lymphoma. A possible model for cancer. N Engl J Med 1987; 316: 79–84.

Levine EG, Bloomfield CD . Cytogenetics of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1990; 10: 7–12.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private view of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of the Army, Department of the Air Force, or Department of Defense.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aguilera, N., Tomaszewski, MM., Moad, J. et al. Cutaneous Follicle Center Lymphoma: A Clinicopathologic Study of 19 Cases. Mod Pathol 14, 828–835 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880398

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880398

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Follicular center helper T-cell (TFH) marker positive mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndrome

Modern Pathology (2013)