Abstract

To achieve fabrication and cost competitiveness in organic optoelectronic devices that include organic solar cells (OSCs) and organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), it is desirable to have one type of material that can simultaneously function as both the electron and hole transport layers (ETLs and HTLs) of the organic devices in all device architectures (i.e., normal and inverted architectures). We address this issue by proposing and demonstrating Cs-intercalated metal oxides (with various Cs mole ratios) as both the ETL and HTL of an organic optoelectronic device with normal and inverted device architectures. Our results demonstrate that the new approach works well for widely used transition metal oxides of molybdenum oxide (MoOx) and vanadium oxide (V2Ox). Moreover, the Cs-intercalated metal-oxide-based ETL and HTL can be easily formed under the conditions of a room temperature, water-free and solution-based process. These conditions favor practical applications of OSCs and OLEDs. Notably, with the analyses of the Kelvin Probe System, our approach of Cs-intercalated metal oxides with a wide mole ratio range of transition metals (Mo or V)/Cs from 1∶0 to 1∶0.75 can offer significant and continuous work function tuning as large as 1.31 eV for functioning as both an ETL and HTL. Consequently, our method of intercalated metal oxides can contribute to the emerging large-scale and low-cost organic optoelectronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic solar cells (OSCs) and organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) have been recognized as attractive candidates for green energy applications. Substantial research progress concerning OSCs and OLEDs has been made in the areas of device fabrication, mechanism, morphology, interface and structure.1,2,3 For instance, OSCs with single and tandem heterojunction structures have been reported with efficiencies of approximately 10%,4,5 which sets a new milestone for high-performance OSCs aimed at conquering the energy crises. OLEDs have been available in the commercial market and have achieved highly efficient performance of RGB (red–green–blue) color and white light displays.6,7,8

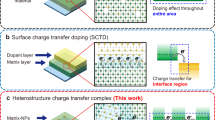

OSCs and OLEDs with efficient and stable performance have been reported using different metal oxides as the electron and hole transport layers (ETLs and HTLs). Metal oxides with a high work function such as MoO3,9,10 V2O5,11 WO312,13 and NiOx14,15 can function as HTLs in organic optoelectronic devices to address the degradation issue of poly(3,4-ethylenedioythiophene):poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS)-based devices.16,17,18 Low-work-function metal oxides such as TiO2,19,20 ZnO21,22,23 and SnOx24 with efficient electron extraction have been utilized as ETLs. Recently, solution-processed metal oxides such as MoO3, V2O5, TiO2 and SnOx with new features of low-temperature and cost-effective processing methods have been developed to improve the availability of organic optoelectronics to the general public.24,25,26,27,28,29,30 Moreover, for instance, Cs-doped TiO2, Cs-doped ZnO, Al-doped ZnO, Al-doped MoO3 and metal oxides incorporated with other functional elements have been developed to realize efficient carrier transport with other features of high conductivity, the carrier blocking effect and optical enhancement.31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 These doped metal oxide interfacial layers require high-temperature annealing or co-evaporation methods, and the film formation is usually limited to either normal or inverted device architecture only.

In this paper, we propose to demonstrate that the Cs-intercalated metal oxide (with different Cs mole ratios) can function as both an ETL and HTL. The metal oxides we studied are molybdenum oxide (MoOx) and vanadium oxide (V2Ox), which are commonly used as HTLs only. In addition, we demonstrate that the Cs-intercalated metal oxide can yield efficient performance and great adaptability in both normal and inverted device architectures of OSCs and OLEDs. Regarding the new approach in forming films of Cs-intercalated metal oxides, it can be easily processed under the simple conditions of room temperature and a water-free and solution-based process, which distinguish this approach from vacuum thermal evaporation or temperature annealing processes. Consequently, the results demonstrate that the new approach can serve as a new and simple route for the emerging technologies of low-cost and large-scale organic optoelectronic devices with normal and inverted device architectures.

Materials and methods

Materials synthesis and preparation

The synthesis of Cs-intercalated and pristine MoOx and V2Ox are based on the molybdenum bronze solution and vanadium bronze solution.27,29,39,40 Molybdenum powder and vanadium powder were purchased from Aladdin Industrial Inc., Shanghai, China. For the molybdenum bronze solution, 0.1 g molybdenum metal powder was dispersed into 10 mL of ethanol using an ultrasound bath, followed by mixing 0.3 mL of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (30%). After 24 h of reaction with a magnetic stirrer, the gray solution turned dark blue, which indicated the formation of hydrogen molybdenum bronzes (HxMoO3) in the solution. For the vanadium bronze solution, 0.1 g vanadium metal powder was dispersed into 10 mL of ethanol using an ultrasound bath, followed by mixing 0.5 mL of H2O2 (30%). After 24 h of reaction with a magnetic stirrer, the solution turned brown, which indicated the formation of hydrogen vanadium bronzes (HxV2O5) in the solution. The remaining solvents of the metal bronze solutions were vaporized in a dry box, after which the molybdenum and vanadium bronze were re-dissolved into ethanol with a concentration of 1 mg mL−1. For Cs-intercalated metal oxides, Cs2CO3 powder was first dissolved in 2-methoxyethanol at a high concentration of 10 mg mL−1. After synthesizing the molybdenum bronze and vanadium bronze solutions, the Cs2CO3 solution was added dropwise into metal bronze solutions with a calculated volume ratio to obtain a certain Cs-intercalated mole ratio in the solutions. Finally, the Cs-intercalated metal bronze solutions were diluted to a total concentration of 1 mg mL−1 with ethanol. The solutions of Cs-intercalated and pristine metal bronze are shown in Figure 1. Further details of the materials synthesis scheme as an additional description with products of each step can be found in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Device fabrication of OSCs and OLEDs OSCs with active layer of poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT):[6,6]-phenyl C61-butyric acid methyl ester (PC61BM)

The OSCs with normal structures of ITO/MoOx/P3HT:PC61BM/MoOx:Cs/Al and ITO/V2Ox/P3HT:PC61BM/V2Ox:Cs/Al were fabricated using the following procedures. The ITO/glass substrates were cleaned with detergent, acetone, ethanol and ultraviolet-ozone treatment for 15 min each. The sheet resistance of the ITO/glass was 15 Ω sq−1. For the HTLs, the MoOx and V2Ox films were formed by spin-coating the molybdenum bronze solution and vanadium bronze solution at 3000 r.p.m. for 30 s at room temperature. The robust polymer blend of P3HT:PC61BM was prepared with a concentration ratio of 20 mg mL−1∶20 mg mL−1 in 1,2-dichlorobenzen. The active layer was fabricated by spin-coating the blended solution at 670 r.p.m. for 30 s, followed by solvent annealing for 1 h and thermal annealing at 120 °C for 10 min in a glove box to form a 220 nm active layer. After the film formation, ETLs using the Cs-intercalated metal oxides layers were formed by spin-coating the corresponding Cs-intercalated metal bronze solution on the active layer at 3000 r.p.m. for 40 s without further treatment. The top electrode of Al was thermally evaporated with a thickness of 100 nm with a mask with a 0.06 cm2 area. For inverted structure OSCs of ITO/MoOx:Cs/P3HT:PC61BM/MoOx/Ag and ITO/V2Ox:Cs/P3HT:PC61BM/V2Ox/Ag, the MoOx:Cs and V2Ox:Cs were formed on the ITO substrate, followed by the active layer formation. HTLs of MoOx and V2Ox were spin-coated on the active layer, and 100 nm Ag was evaporated onto the HTL metal oxides. The device size in this work is 0.06 cm2 unless specified otherwise.

OSCs with active layer of poly[(((2-hexyldecyl)sulfonyl)-4,6-di(thiophen-2-yl)thieno[3,4-b]thiophene-2,6-diyl)-alt-(4,8-bis((2-ethylhexyl)oxy)benzo[1,2-b:4,5-b']dithiophene-2,6-diyl)] (PBDTDTTT-S-T)41:[6,6]-phenyl C71-butyric acid methyl ester (PC71BM)

The OSCs with the normal structures of ITO/MoOx/PBDTDTTT-S-T:PC71BM/MoOx:Cs/Al and ITO/V2Ox/PBDTDTTT-S-T:PC71BM/V2Ox:Cs/Al were fabricated by preparing the blended solution of PBDTDTTT-S-T:PC71BM with a concentration of 8 mg mL−1∶12 mg mL−1 in chlorobenzene with an additive of 3% v/v 1,8-diiodooctane (DIO). The film formation of the HTLs and ETLs used the same procedure with the OSCs based on P3HT:PC61BM. The active layer was formed by spin-coating the prepared blended solution at 2500 r.p.m. for 50 s with a thickness of 110 nm. Then, the active layer was placed into a vacuum chamber of ∼10 Pa for 4 h to remove the additive DIO. After the formation of Cs-intercalated metal oxides, the top electrode of Al was evaporated with a shadow mask of 0.06 cm2 area and 100 nm thickness. The inverted structure OSCs of ITO/MoOx:Cs/PBDTDTTT-S-T:PC71BM/MoOx/Ag and ITO/V2Ox:Cs/PBDTDTTT-S-T:PC71BM/V2Ox/Ag were fabricated using the reverse sequence of the normal OSCs.

OLEDs with active layer of poly[2-(4-(3′,7′-dimethyloctyloxy)-phenyl)-p-phenylene-vinylene] (P-PPV)42

The light-emitting material of the P-PPV solution of 8 mg mL−1 in p-xylene was prepared. The active layer was formed by spin-coating the solution at 2000 r.p.m. for 60 s with a thickness of 80 nm. The formation of the HTLs and ETLs using MoOx (or V2Ox) and MoOx:Cs (or V2Ox:Cs) was performed using the same procedure for both the normal and inverted structure. Normal structure OLEDs of ITO/MoOx(V2Ox)/P-PPV/MoOx:Cs(V2Ox:Cs)/Al and inverted OLEDs of ITO/MoOx:Cs(V2Ox:Cs)/P-PPV/MoOx(V2Ox)/Ag were fabricated in the study.

Measurements and characterizations

The work function of various Cs-intercalated and pristine metal oxides were measured using a SKP5050 scanning Kelvin Probe System with a resolution 1–3 meV from KP Technology Ltd. The Kelvin Probe measurement used a new layer of highly ordered pyrolytic graphite as a reference (4.6 eV) to calculate the absolute work function values of different carrier transport layers. The thicknesses of the Cs-intercalated and pristine metal oxides were measured using Woollam spectroscopic ellipsometry. The OSCs were evaluated by illumination under an ABET AM 1.5 G solar simulator with a light intensity of 100 mW cm−2. The current density–voltage (J–V) characterizations of the OSCs were performed using a Keithley source meter. The incident photon-to-current conversion efficiency of different structure OSCs were measured using a home-built system with a Newport xenon lamp incorporated with an Acton monochromator, a pre-amplifier and a Stanford lock-in amplifier. For the OLED characterizations, the current density–voltage–luminance (J–V–L) and luminance efficiency–current density–luminance (LE–J–L) were tested using a Keithley source meter with a calibrated Si photodiode. The electroluminescence spectra were obtained under a driving current density of 100 mA cm−2 using an Oriel spectrometer integrated with a charge-coupled device.

Results and discussion

Electrical properties of Cs-intercalated metal oxide for HTL and ETL

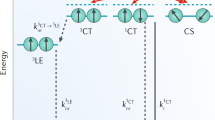

The energy level alignment of interfacial layers with the active layer has great significance for the performance of OSCs.43,44 Here, we use a Kelvin Probe system to investigate the work function of various Cs-intercalation mole ratios of MoOx and V2Ox. The MoOx and V2Ox films formed on ITO/glass substrates exhibit work functions of 5.30 eV and 5.42 eV, respectively. By incorporating Cs into the metal oxides, the work function of the intercalated metal oxides exhibits a continuous modification with increasing Cs mole ratio. The work functions of the Cs-intercalated and pristine metal oxides are listed in Table 1. Remarkably, the work function can be continuously tuned to as large as 1.14 eV for MoOx and 1.31 eV for V2Ox. Figure 2 illustrates the work function tuning abilities of MoOx and V2Ox using the Cs-intercalation method.

In organic optoelectronic devices, for instance, the commonly used acceptor material PC61BM has the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital of 4.20 eV. With an intercalated mole ratio of 1∶0.5, the work function of the Cs-intercalated metal oxides will become similar to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital of the acceptor, which indicates a good energy level alignment formed between the two layers.43 Because the pristine MoOx and V2Ox have high work functions of 5.30 eV and 5.42 eV, respectively, HTLs of pristine metal oxides can have ohmic contact with a P3HT highest occupied molecular orbital of 5.10 eV and PBDTDTTT-S-T highest occupied molecular orbital of 5.04 eV.41 For both normal and inverted structures, organic optoelectronic devices using Cs-intercalated metal oxides as the ETL and pristine metal oxides as the HTL can exhibit good performance. The energy level of different materials and different device architectures used in this work are summarized and presented in Figure 3. Details of the performance and characteristics of the devices are presented in the following discussion sections.

The Kelvin Probe System measurements demonstrate that the work function of MoOx and V2Ox can be effectively modified using the Cs-intercalation method. With this simple intercalation method, the continuous tuning ability of the work function of metal oxides to as large as 1.31 eV can be achieved. Thus, one metal oxide functioning as both the HTL and ETL through the transition of a high work function to a low work function can be achieved. In particular, room-temperature Cs-intercalated metal oxides functioning as the electron transport layer are not realized only by the Cs2CO3 existing within the film. As indicated by a previous paper, the Cs2CO3 will be decomposed into Cs2O doped with Cs2O2 by thermal annealing process or thermal evaporation, which functions as an n-type semiconductor with more desirable electron transport properties.45 However, the performance of OSCs was not satisfied when using only room-temperature solution-processed Cs2CO3 as the ETL without annealing treatment. The J-V curves of inverted structure OSCs using room-temperature solution-processed Cs2CO3, MoOx:Cs and V2Ox:Cs working as ETLs are presented in Supplementary Fig. S2. The comparison illustrates that the Cs-intercalated metal oxide functioning as the ETL is achieved by the Cs-intercalation process within the metal oxide rather than the existence of Cs2CO3. Consequently, Cs-intercalated metal oxides exhibit a remarkable continuously work function tuning ability and adjustment of energy level favoring applications as both ETLs and HTLs in organic optoelectronic devices.

Device performance of OSCs and OLEDs with Cs-intercalated and pristine metal oxides as the ETL and HTL P3HT-based normal and inverted OSCs

Both the normal and inverted structures of ITO/MoOx(V2Ox)/P3HT:PC61BM/MoOx:Cs(V2Ox:Cs)/Al and ITO/MoOx:Cs(V2Ox:Cs)/P3HT:PC61BM/MoOx(V2Ox)/Ag were fabricated to evaluate the performance of devices with different metal oxides. The thickness and Cs-intercalated mole ratio optimizations of each carrier transport layer are given in Supplementary Figs. S3 and S4. The performance of the normal structure P3HT-based OSC using MoOx and Cs-intercalated MoOx (optimized mole ratio Mo/Cs 1∶0.5) exhibits a short-circuit current density (JSC) of 9.05 mA cm−2, open-circuit voltage (VOC) of 0.61 V, fill factor (FF) of 63.24% and power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 3.50%. The normal structure P3HT-based OSC using V2Ox and Cs-intercalated V2Ox (optimized mole ratio V/Cs 1∶0.5) exhibits a JSC of 9.41 mA cm−2, VOC of 0.61 V, FF of 62.54% and PCE of 3.59%. The inverted structure OSC using Cs-intercalated MoOx and pristine MoOx exhibits a JSC of 9.24 mA cm−2, VOC of 0.60 V, FF of 57.65% and PCE of 3.20%. And the inverted structure OSC using Cs-intercalated V2Ox and pristine V2Ox exhibits a JSC of 9.22 mA cm−2, VOC of 0.60 V, FF of 58.02% and PCE of 3.21%. The results of the different device performances are summarized in Table 2, and the J–V curves are presented in Figure 4. Based on the results, OSCs using Cs-intercalated and pristine metal oxides exhibit comparable performance in both normal and inverted device structures. The corresponding Jdark–V and incident photon-to-current conversion efficiency of OSCs with different structures are presented in Supplementary Figs. S5 and S6. As references devices, OSCs without any ETL were also fabricated and measured. From the results summarized in Supplementary Table S1 and Fig. S7, it can be observed that organic optoelectronic devices perform poorly without Cs-intercalated metal oxides as the ETLs.

PBDTDTTT-S-T-based normal and inverted OSCs

To demonstrate high-efficiency performance OSCs with the Cs-intercalated and pristine metal oxides as the ETL and HTL, respectively, OSCs were fabricated using the low band gap polymer PBDTDTTT-S-T blended with PC71BM as the active layer. Both the normal and inverted structures of ITO/MoOx(V2Ox)/PBDTDTTT-S-T:PC71BM/MoOx:Cs(V2Ox:Cs)/Al and ITO/MoOx:Cs(V2Ox:Cs)/PBDTDTTT-S-T:PC71BM/MoOx(V2Ox)/Ag were studied. As shown in the Figure 5, the normal and inverted structures of the OSCs provide comparable performance as discussed below. The J–V characteristics are summarized in Table 3. The best performing PBDTDTTT-S-T-based OSCs with the structure of ITO/V2Ox/PBDTDTTT-S-T:PC71BM/V2Ox:Cs/Al exhibits a JSC of 16.29 mA cm−2, VOC of 0.68 V, FF of 67.21% and PCE of 7.44%, which is comparable to the characteristics of reported PBDTDTTT-S-T-based OSCs with the normal structure of ITO/PEDOT:PSS/active layer/Ca/Al as the HTL and ETL.41 This finding indicates the excellent electron and hole extraction abilities compared with the non-metal oxides carrier transport layers. Moreover, using Cs-intercalated and pristine metal oxides as carrier transport layers, OSCs can be prepared with both normal and inverted structures. As demonstrated in Table 3, all the normal and inverted OSCs exhibit good performance. The slight reduction of performance could be explained by the effects of different morphology and phase separation conditions of OSCs with different structures.46,47 As demonstrated in Supplementary Figs. S8 and S9, the good Jdark–V and incident photon-to-current conversion efficiency characteristics of OSCs using Cs-intercalated and pristine metal oxides yield efficient performance with various structures of OSCs. The performances of reference OSCs without Cs-intercalated metal oxides as the ETL are summarized in Supplementary Table S1 and Fig. S7.

P-PPV-based normal and inverted OLEDs

OLEDs are also demonstrated with Cs-intercalated and pristine metal oxides as the ETL and HTL. Normal and inverted structures of ITO/MoOx(V2Ox)/P-PPV/MoOx:Cs(V2Ox:Cs)/Al and ITO/MoOx:Cs(V2Ox:Cs)/P-PPV/MoOx(V2Ox)/Ag were fabricated with 80 nm thickness for the light-emitting layer. The J–V–L and LE–J–L characteristics of different OLEDs are shown in Figure 6. The normal structure OLED with MoOx-based carrier transport layers exhibits a turn-on voltage (VON) of 5.5 V and a maximum luminance (LMAX) of 23 316 cd m−2 at 11.75 V, whereas the V2Ox-based normal structure OLED exhibits a VON of 5 V and LMAX of 30 983 cd m−2 at 11.25 V. The inverted-structure OLEDs also exhibit comparable performance as the normal structures. For MoOx:Cs and MoOx, the inverted OLED exhibits a VON of 5.75 V and LMAX of 22 316 cd m−2 at 11.75 V. For V2Ox:Cs and V2Ox, the inverted OLED exhibits a VON of 5.25 V and LMAX of 28533 cd m−2 at 11.5 V. The normalized electroluminescence spectra of OLEDs with different structures are shown in Supplementary Fig. S10. The results of the OLEDs with different structures indicate the good charge injection capabilities of Cs-intercalated and pristine metal oxides. The reference devices characteristics of OLEDs without any ETL are shown in Supplementary Fig. S11.

As a summary of organic optoelectronic devices, OSCs and OLEDs with Cs-intercalated and pristine metal oxides using different active layers materials exhibit comparable device performance with different device architectures. Both the normal and inverted devices architectures exhibit good device performance. The results illustrate that Cs-intercalated metal oxides offer a simple method to achieve a large continuous tuning of the work function and structure adaptability for organic optoelectronic devices. Consequently, the organic optoelectronic devices exhibit good performance for both normal and inverted device architectures using Cs-intercalated and pristine metal oxides as the ETL and HTL, respectively.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated a unified synthesis method for using Cs-intercalated and pristine MoOx and V2Ox as ETLs and HTLs in OSCs and OLEDs. This method has the attractive features of being a room-temperature, solution-based and water-free process as well as producing high-quality interface layers in both normal and inverted device architectures. Kelvin Probe System measurement results indicate that the continuous variation of the work function can be over 1 eV for the Cs-intercalated metal oxides. The comparable performances of OSCs and OLEDs with different devices structures demonstrate the great adaptability and insensitivity achieved using metal oxides with the incorporation of Cs. The performance of organic optoelectronic devices can be fully achieved without obvious barriers existing at the interface. This new approach can be used to simplify the fabrication procedures of OSCs and OLEDs and has great potential for the preparation of organic optoelectronic devices.

References

Mihailetchi VD, Koster LJ, Hummelen JC, Blom PW . Photocurrent generation in polymer-fullerene bulk heterojunctions. Phys Rev Lett 2004; 93: 216601.

Koster LJ, Smits EC, Mihailetchi VD, Blom PW . Device model for the operation of polymer/fullerene bulk heterojunction solar cells. Phys Rev B 2005; 72: 085205.

Peet J, Kim JY, Coates NE, Ma WL, Moses D et al. Efficiency enhancement in low-bandgap polymer solar cells by processing with alkane dithiols. Nat Mater 2007; 6: 497– 500.

He Z, Zhong C, Su S, Xu M, Wu H et al. Enhanced power-conversion efficiency in polymer solar cells using an inverted device structure. Nat Photonics 2012; 6: 591– 595.

You J, Dou L, Yoshimura K, Kato T, Ohya K et al. A polymer tandem solar cell with 10.6% power conversion efficiency. Nat Commun 2013; 4: 1446.

Reineke S, Lindner F, Schwartz G, Seidler N, Walzer K et al. White organic light-emitting diodes with fluorescent tube efficiency. Nature 2009; 459: 234– 238.

Zheng H, Zheng Y, Liu N, Ai N, Wang Q et al. All-solution processed polymer light-emitting diode displays. Nat Commun 2013; 4: 1971.

Zhang Q, Li B, Huang S, Nomura H, Tanaka H et al. Efficient blue organic light-emitting diodes employing thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Nat Photonics 2014; 8: 326– 332.

Cao Y, Yu G, Parker ID, Heeger AJ . Ultrathin layer alkaline earth metals as stable electron-injecting electrodes for polymer light emitting diodes. J Appl Phys 2000; 88: 3618– 3623.

Shrotriya V, Li G, Yao Y, Chu CW, Yang Y . Transition metal oxides as the buffer layer for polymer photovoltaic cells. Appl Phys Lett 2006; 88: 073508.

Li G, Chu CW, Shrotriya V, Huang J, Yang Y . Efficient inverted polymer solar cells. Appl Phys Lett 2006; 88: 253503.

Han S, Shin WS, Seo M, Gupta D, Moon SJ et al. Improving performance of organic solar cells using amorphous tungsten oxides as an interfacial buffer layer on transparent anodes. Org Electron 2009; 10: 791– 797.

Stubhan T, Li N, Luechinger NA, Halim SC, Matt GJ et al. High fill factor polymer solar cells incorporating a low temperature solution processed WO3 hole extraction layer. Adv Energy Mater 2012; 2: 1433– 1438.

Ratcliff EL, Meyer J, Steirer KX, Garcia A, Berry JJ et al. Evidence for near-surface NiOOH species in solution-processed NiOx selective interlayer materials: impact on energetics and the performance of polymer bulk heterojunction photovoltaics. Chem Mater 2011; 23: 4988– 5000.

Garcia A, Welch GC, Ratcliff EL, Ginley DS, Bazan GC et al. Improvement of interfacial contacts for new small-molecule bulk-heterojunction organic photovoltaics. Adv Mater 2012; 24: 5368– 5373.

de Jong MP, van IJzendoorn LJ, de Voigt MJA . Stability of the interface between indium-tin-oxide and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)/poly(styrenesulfonate) in polymer light-emitting diodes. Appl Phys Lett 2000; 77: 2255– 2257.

Wong KW, Yip HL, Luo Y, Wong KY, Lau WM et al. Blocking reactions between indium-tin oxide and poly (3,4-ethylene dioxythiophene):poly(styrene sulphonate) with a self-assembly monolayer. Appl Phys Lett 2002; 80: 2788– 2790.

Ionescu-Zanetti C, Mechler A, Carter SA, Lal R . Semiconductive polymer blends: correlating structure with transport properties at the nanoscale. Adv Mater 2004; 16: 385– 389.

Kim JY, Kim SH, Lee HH, Lee K, Ma W et al. New Architecture for high-efficiency polymer photovoltaic cells using solution-based titanium oxide as an optical spacer. Adv Mater 2006; 18: 572– 576.

Wang J, Polleux J, Lim J, Dunn B . Pseudocapacitive contributions to electrochemical energy storage in TiO2 (anatase) nanoparticles. J Phys Chem C 2007; 111: 14925– 14931.

Gilot J, Barbu I, Wienk MM, Janssen RAJ . The use of ZnO as optical spacer in polymer solar cells: theoretical and experimental study. Appl Phys Lett 2007; 91: 113520.

Sun Y, Seo JH, Takacs CJ, Seifter J, Heeger AJ . Inverted polymer solar cells integrated with a low-temperature-annealed sol–gel-derived ZnO film as an electron transport layer. Adv Mater 2011; 23: 1679– 1683.

Kyaw AKK, Wang DH, Wynands D, Zhang J, Nguyen TQ et al. Improved light harvesting and improved efficiency by insertion of an optical spacer (ZnO) in solution-processed small-molecule solar cells. Nano Lett 2013; 13: 3796– 3801.

Trost S, Zilberberg K, Behrendt A, Riedl T . Room-temperature solution processed SnOx as an electron extraction layer for inverted organic solar cells with superior thermal stability. J Mater Chem 2012; 22: 16224– 16229.

Tan Za, Zhang W, Cui C, Ding Y, Qian D et al. Solution-processed vanadium oxide as a hole collection layer on an ITO electrode for high-performance polymer solar cells. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2012; 14: 14589– 14595.

Wang F, Xu Q, Tan Z, Qian D, Ding Y et al. Alcohol soluble titanium(IV) oxide bis(2,4-pentanedionate) as electron collection layer for efficient inverted polymer solar cells. Org Electron 2012; 13: 2429– 2435.

Xie F, Choy WCH, Wang C, Li X, Zhang S et al. Low-temperature solution-processed hydrogen molybdenum and vanadium bronzes for an efficient hole-transport layer in organic electronics. Adv Mater 2013; 25: 2051– 2055.

Tan Za, Qian D, Zhang W, Li L, Ding Y et al. Efficient and stable polymer solar cells with solution-processed molybdenum oxide interfacial layer. J Mater Chem A 2013; 1: 657– 664.

Li X, Choy WCH, Xie F, Zhang S, Hou J . Room-temperature solution-processed molybdenum oxide as a hole transport layer with Ag nanoparticles for highly efficient inverted organic solar cells. J Mater Chem A 2013; 1: 6614– 6621.

Hadipour A, Müller R, Heremans P . Room temperature solution-processed electron transport layer for organic solar cells. Org Electron 2013; 14: 2379– 2386.

Park MH, Li JH, Kumar A, Li G, Yang Y . Doping of the metal oxide nanostructure and its influence in organic electronics. Adv Funct Mater 2009; 19: 1241– 1246.

Bolink HJ, Brine H, Coronado E, Sessolo M . Phosphorescent hybrid organic–inorganic light-emitting diodes. Adv Mater 2010; 22: 2198– 2201.

Sessolo M, Bolink HJ . Hybrid organic–inorganic light-emitting diodes. Adv Mater 2011; 23: 1829– 1845.

Park SY, Kim BJ, Kim K, Kang MS, Lim KH et al. Low-temperature, solution-processed and alkali metal doped ZnO for high-performance thin-film transistors. Adv Mater 2012; 24: 834– 838.

Liu J, Shao S, Fang G, Meng B, Xie Z et al. High-efficiency inverted polymer solar cells with transparent and work-function tunable MoO3–Al composite film as cathode buffer layer. Adv Mater 2012; 24: 2774– 2779.

Brine H, Sánchez-Royo JF, Bolink HJ . Ionic liquid modified zinc oxide injection layer for inverted organic light-emitting diodes. Org Electron 2013; 14: 164– 168.

Jiang X, Wong FL, Fung MK, Lee ST . Aluminum-doped zinc oxide films as transparent conductive electrode for organic light-emitting devices. Appl Phys Lett 2003; 83: 1875– 1877.

Murdoch GB, Hinds S, Sargent EH, Tsang SW, Mordoukhovski L et al. Aluminum doped zinc oxide for organic photovoltaics. Appl Phys Lett 2009; 94: 213301.

Douvas AM, Vasilopoulou M, Georgiadou DG, Soultati A, Davazoglou D et al. Sol–gel synthesized, low-temperature processed, reduced molybdenum peroxides for organic optoelectronics applications. J Mater Chem C 2014; 2: 6290– 6300.

Soultati A, Douvas AM, Georgiadou DG, Palilis LC, Bein T et al. Solution-processed hydrogen molybdenum bronzes as highly conductive anode interlayers in efficient organic photovoltaics. Adv Energy Mater 2014; 4: 1300896

Huang Y, Guo X, Liu F, Huo L, Chen Y et al. Improving the ordering and photovoltaic properties by extending π-conjugated area of electron-donating units in polymers with D–A structure. Adv Mater 2012; 24: 3383– 3389.

Becker H, Spreitzer H, Kreuder W, Kluge E, Schenk H et al. Soluble PPVs with enhanced performance—a mechanistic approach. Adv Mater 2000; 12: 42– 48.

Mihailetchi VD, Blom PWM, Hummelen JC, Rispens MT . Cathode dependence of the open-circuit voltage of polymer: fullerene bulk heterojunction solar cells. J Appl Phys 2003; 94: 6849– 6854.

Greiner MT, Helander MG, Tang WM, Wang ZB, Qiu J et al. Universal energy-level alignment of molecules on metal oxides. Nat Mater 2012; 11: 76– 81.

Liao HH, Chen LM, Xu Z, Li G, Yang Y . Highly efficient inverted polymer solar cell by low temperature annealing of Cs2CO3 interlayer. Appl Phys Lett 2008; 92: 173303.

Campoy-Quiles M, Ferenczi T, Agostinelli T, Etchegoin PG, Kim Y et al. Morphology evolution via self-organization and lateral and vertical diffusion in polymer: fullerene solar cell blends. Nat Mater 2008; 7: 158– 164.

Xu Z, Chen LM, Yang G, Huang CH, Hou J et al. Vertical phase separation in poly(3-hexylthiophene): fullerene derivative blends and its advantage for inverted structure solar cells. Adv Funct Mater 2009; 19: 1227– 1234.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the University Grant Council of the University of Hong Kong (Grant Nos. 10401466 and 201111159062), the General Research Fund (Grant Nos. HKU711813 and HKU711612E), an RGC-NSFC grant (N_HKU709/12) and grant CAS14601 from the CAS-Croucher Funding Scheme for Joint Laboratories.

Note: Accepted article preview online 15 January 2015

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Note: Supplementary Information for this article can be found on the Light: Science & Applications' website.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Xie, F., Zhang, S. et al. MoOx and V2Ox as hole and electron transport layers through functionalized intercalation in normal and inverted organic optoelectronic devices. Light Sci Appl 4, e273 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2015.46

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2015.46

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Approaching Ohmic hole contact via a synergetic effect of a thin insulating layer and strong electron acceptors

Science China Materials (2021)

-

Recent advances in thermally activated delayed fluorescence for white OLEDs applications

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2020)

-

Undoped highly efficient green and white TADF-OLEDs developed by DMAC-BP: manufacturing available via interface engineering

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2020)

-

Tailoring electroluminescence characteristics with enhanced electron injection efficiency in organic light emitting diodes by doping engineering

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2019)

-

S-1805/Ag/Au Hybrid Transparent Electrodes for ITO-free Flexible Organic Photovoltaics

Chemical Research in Chinese Universities (2019)