Abstract

The solar cell market is predominantly based on textured screen-printed solar cells. Due to parasitic absorption in nanostructures, using plasmonic processes to obtain an enhancement that exceeds 2.5% of the short-circuit photocurrent density is challenging. In this paper, a 7.2% enhancement in the photocurrent density can be achieved through the integration of plasmonic Al nanoparticles and wrinkle-like graphene sheets. For the first time, we experimentally achieve Al nanoparticle-enhanced solar cells. An innovative thermal evaporation method is proposed to fabricate low-coverage Al nanoparticle arrays on solar cells. Due to the ultraviolet (UV) plasmon resonance of Al nanoparticles, the performance enhancement of the solar cells is significantly greater than that from Ag nanoparticles. Subsequently, we deposit wrinkle-like graphene sheets over the Al nanoparticle-enhanced solar cells. Compared with planar graphene sheets, the bend carbon layer also exhibits a broadband light-trapping effect. Our results exceed the limit of plasmonic light trapping in textured screen-printed silicon solar cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Scientists have recently discovered that plasmonic effects from metallic nanoparticles are capable of significantly improving solar cell performance.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 Because plasmonic nanoparticles are integrated into photovoltaic devices with relatively low surface coverages (typically less than 30%), light-trapping effects increase solar cell absorption and enhance the short-circuit photocurrent density (Jsc) of not only new-generation solar cells (organic solar cells and dye-sensitized solar cells),1,2 but textured screen-printed silicon solar cells12,13 which dominate the photovoltaic market. However, plasmonic nanostructures suffer from parasitic absorption that cannot contribute to photocurrents; thus, the performance of plasmonic solar cells is limited.1,15 Using plasmonic light-trapping to increase the Jsc of textured screen-printed solar cells by more than 2.5% is challenging.14 Therefore, a novel method to exceed the Jsc enhancement limit, in which the parasitic absorption of the nanostructure must be considered, is critical.

Below the plasmon resonance of nanostructures, a negative influence named Fano effect can be generated from the destructive interference between the scattered and unscattered light, causing reduced light absorption in solar cells at short wavelengths.16 Among plasmonic materials, only the plasmon resonance of Al nanoparticles exhibits in the ultraviolet (UV) range, where the intensity of solar irradiance is negligible. Consequently, Al nanoparticle-enhanced photovoltaic devices have much greater potential to avoid the Fano effect, compared with the solar cells integrated by Ag and Au nanoparticles. However, current research on plasmonic solar cells focuses on Ag nanoparticle-enhanced and Au nanoparticle-enhanced solar cells.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,13,14 Al nanoparticle-enhanced solar cells have not been realized because a method to simultaneously synthesize Al nanoparticles and control the low surface coverage has not been developed. An Al nanostructure is too active to be produced by a wet-chemical method under ambient temperatures. Although it can be obtained through the evaporation of a metal thin film onto the solar cell surface followed by an annealing process, surface coverage less than 30% is difficult to be achieved.17 With high coverage, the nanoparticles block a significant amount of light, which reduces solar cell absorption.

On the other hand, to achieve the maximum Jsc, other light-trapping materials should be integrated into plasmonic solar cells. Because the materials need to be deposited on screen-printed solar cells using conventional light-trapping structures (pyramid textures and antireflection coatings), the materials should be sufficiently thin to allow conformable attachment, and the optical transmittance of the materials should be high enough to maintain solar cell absorption. Graphene, which is a two-dimensional carbon material, exhibits extremely high transmittance.18 However, due to the challenges of morphology control, graphene materials with significant light-trapping effects in solar cells have not been discovered.

In this paper, an innovative method is presented for solving two bottleneck issues, i.e., the fabrication of low surface coverage by Al nanoparticles and the synthesis of a graphene light-trapping layer. This innovative physical method is used to prepare Al nanoparticle suspensions. After the fabrication of the low-coverage Al nanoparticle arrays from the suspensions on the front sides of textured screen-printed solar cells, wrinkle-like graphene sheets can be integrated in the Al-enhanced solar cells. An improvement in the Jsc of 7.2% can be achieved by light trapping from both plasmonic Al nanoparticles and wrinkle-like graphene sheets.

Materials and methods

Al nanoparticles were synthesized by a modified thermal evaporation method. Using thermal evaporation, Al thin films with different thicknesses were deposited over NaCl substrate powders. Al nanoparticles of different diameters were synthesized by adjusting the evaporation thicknesses of Al thin films and the annealing temperature (Supplementary Tab. S1). After annealing, the powder was mixed with water by vigorous stirring, and the Al nanoparticle suspension was obtained by centrifugation and washing. For comparison, 100 nm Ag nanoparticles were synthesized by NaBH4 reduction of silver nitrate solutions.19 The suspension of graphene sheets was synthesized by the chemical reduction of graphite via a modified Hummers method.20 First, graphite and NaNO3 were mixed with concentrated H2SO4. Through vigorous stirring, the reducing agent, KMnO4, was added to the suspension. H2O2 was subsequently added to the mixture at 98 °C. A graphene oxide suspension was obtained after the purification. The suspension of the graphene sheet can be prepared by the chemical reduction of graphene oxide. NaBH4 or hydrazine was added to the graphene oxide suspension, and the mixture was heated at 100 °C for 2 h. After the reaction, the graphene product was centrifuged, washed and dried.

Low-coverage Al nanoparticle arrays and wrinkle-like graphene sheets can be fabricated on the front sides of textured screen-printed solar cells by placing the sample suspensions dropwise.11 The surface coverage can be tailored by adjusting the suspension concentrations. The single screen-printed crystalline solar cells, which were purchased from Suntech Power Holdings Co., Ltd., were composed of p-type Si wafers with geometries of silver finger/75 nm SiN/180 µm c-Si with front texture and Ag/Al back contact.

The morphologies of the Al nanoparticles and wrinkle-like graphene sheets were observed by a scanning electron microscope (SEM) system (ZEISS Supra 40); a spectrometer (Perkin Elmer, Lambda 1050) was employed to measure the optical spectra. The reflectance (R) of the solar cells was measured with an integrating sphere and the absorption (A) was calculated by A=100%−R. The photovoltaic performances of the solar cells were characterized by a simulated AM 1.5 spectrum (Oriel-Sol 3A-94023) and external quantum efficiency (EQE) measurements (PV Measurement QEX10).

Results and discussion

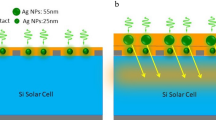

The geometry of the Al nanoparticle/graphene-enhanced solar cell is shown in Figure 1a, in which Al nanoparticles and wrinkle-like graphene sheets are integrated on the front sides of solar cells to trap the incident light into the silicon absorbing layer. As shown in Figure 1b, the plasmon resonance of Al nanoparticles is exhibited in the UV range to prevent a decrease in solar cell absorption in the short wavelength region caused by the Fano effect.12 In the absorption spectrum of the wrinkle-like graphene sheets (Figure 1c), a characteristic sp2 absorption peak is located at approximately 280 nm.21 Another peak is discernible at 840 nm,22 unlike the planar graphene sheet (Supplementary Fig. S1).23 Because carbon-nanotube thin film demonstrates an absorption peak in a wavelength range similar to electronic intermediate transition,24,25 we suggest that the long-wavelength peak is attributed to the bend carbon layer of the wrinkle-like graphene sheets. Graphene light trapping can further increase the absorption of Al nanoparticle-enhanced solar cells.

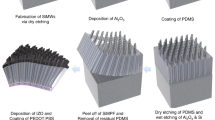

The key to fabricate low-coverage Al nanoparticle arrays is to obtain the particle suspension first. Then the integration experiments can be conducted by suspension deposition, and the surface coverage can be easily controlled by adjustments of the suspension concentrations. Figure 2a presents a schematic of the synthesis of Al nanoparticles using an innovative physical method. The NaCl powder was employed as the substrate during the evaporation of Al thin films because it was stable and soluble after high-temperature treatment. Subsequently, we used water to remove NaCl powders and obtained Al nanoparticle aqueous suspensions. Using the suspensions, we easily controlled the particle surface coverage, especially coverage below 30%.

(a) Realization processes of Al nanoparticles for the fabrication of plasmonic solar cells, using an innovative thermal evaporation method; (b) SEM images of Al nanoparticles (scale bar: 200 nm); (c) Jsc enhancements of textured screen-printed solar cells integrated with Al and Ag nanoparticles of different diameters and surface coverages; (d) EQE enhancement of screen-printed solar cells through the integration of 100 nm Al (red) and 100 nm Ag (blue) particles with 10% coverage; (e) Absorbing cross-sections of 100 nm Al (red) and 100 nm Ag (blue) particles. EQE, external quantum efficiency; SEM, scanning electron microscope.

The SEM image of Al nanoparticles is shown in Figure 2b. Because the thickness of Al thin film is 10 nm, Al nanoparticles with average diameters of 100 nm (Supplementary Fig. S2) can be synthesized by annealing at 400 °C for 90 min. The surface coverage of the particles was approximately 10%, which is much lower than the surface coverage fabricated by other evaporation methods.17

The influence of the Al nanoparticle integration on the performances of solar cells was investigated through the relationship between the Jsc enhancements and the diameters of the Al nanoparticles (Supplementary Fig. S3) under different surface coverages, as shown in Figure 2c. For the Al nanoparticle sizes ranging from 50 to 150 nm, 10% surface coverage provides optimum photovoltaic performances of the solar cells among all the three coverages. Al nanoparticles facilitate the forward scattering of the incident light into a distribution of angles, thus, increasing the optical path length in the silicon absorbing layer.12 The 5% coverage is insufficient for a significant enhancement of the Jsc, whereas 20% surface coverage causes blocking of the incident light, which reduces light absorption in the crystalline silicon layer.12 Under the coverage of 10%, the optimized particle size for the performance improvement is 100 nm, due to the strong light absorption of the small nanoparticles and the weak forward scattering of the large particles through the strong high-order plasmon excitation.26 In this case, Jsc increases by 6.3% and the energy conversion efficiency increases considerably from 18.24% to 19.36%, as shown in Table 1. The plasmon resonance peak of 100 nm Ag nanoparticles is visible at a wavelength of 410 nm (Supplementary Fig. S4). Once the Ag nanoparticles were deposited on the textured screen-printed solar cells with 10% surface coverage, only a marginal enhancement of Jsc 0.8% was observed. The EQE enhancement curves that are presented in Figure 2d indicate that Al nanoparticles produce significant light scattering below 1000 nm due to their unique plasmonic properties, whereas the Fano effect of the silver nanoparticles causes a decrease in EQE below 400 nm.

Finite-difference time-domain software from Lumerical,27 as shown in Figure 2e, was employed to calculate the absorption cross-sections, Qabs, of 100 nm Al particle and 100 nm Ag particle. Compared with the Ag particle, the Al particle exhibits significantly lower parasitic absorption in the short wavelength region due to UV plasmon resonance.12 However, a larger absorption cross-section is exhibited in the long wavelength. To further enhance the light trapping of solar cell absorption in the long wavelength, graphene sheets were prepared (Figure 3a–b); the SEM image is displayed in Figure 3c. The typical wrinkle-like feature is distinct, which is a result of the graphite layer treatment by the strong reductant NaBH4. The Raman spectrum of the wrinkle-like graphene sheets was also measured. A strong D band of approximately 1340 nm (Supplementary Fig. S5) indicates that the graphene product contains many defects on the carbon sheet formed during the NaBH4 reduction,28 which causes the sheets to wrinkle.29,30,31 Once the reductant was changed to a relatively mild agent, hydrazine, planar graphene sheets can be synthesized because fewer defects are generated by the hydrazine treatment than the planar graphene sheets generated by NaBH4 reduction.

Schematic drawings of the synthesis of (a) planar graphene sheets and (b) wrinkle-like graphene sheets; (c) SEM images of wrinkle-like graphene sheets (scale bar: 500 nm); (d) Jsc enhancements of textured screen-printed solar cells integrated with wrinkle-like (red) and planar (blue) graphene sheets with different surface coverages; (e) EQE enhancements of screen-printed solar cells through the integration of wrinkle-like (red) and planar (blue) graphene sheets with 10% surface coverage. EQE, external quantum efficiency; SEM, scanning electron microscope.

The textured screen-printed solar cells incorporated into the wrinkle-like graphene sheets clearly demonstrate a significant enhancement in Jsc compared with those integrated by the planar sheets, as shown in Figure 3d. An optimized surface coverage of 10% was produced by the balance between light trapping and light blocking. These improvements in Jsc are further validated by the EQE measurement in Figure 3e. It has been demonstrated that the planar sheets can substantially trap short-wavelength light. Because the refractive index of the graphene sheets is lower than that of the SiN layer below 600 nm (Supplementary Fig. S6), an extra antireflection mechanism is available, which causes an increase in the EQE of this wavelength range. In contrast, the EQE results indicate that the incident light from the wrinkle-like sheets, for both short and long wavelengths, is trapped inside the crystalline silicon layer and contributes to the Jsc enhancement. An additional enhancement of approximately 850–1100 nm in long wavelengths can be achieved by the wrinkle-like sheets. We attribute the light scattering of the wrinkle structure to this enhancement. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S7, the wrinkle-like sheet can be used to achieve substantial angle scattering, which was not observed in the planar sheet.

Based on the optimized Al nanoparticle-enhanced solar cells, an additional improvement in performance was achieved by the integration of the wrinkle-like graphene sheets. In this study, Al nanoparticles and wrinkle-like sheets were incorporated on the front sides of the textured screen-printed solar cells (Supplementary Fig. S8). As presented in Table 1, 19.54% conversion efficiency can be achieved with 10% coverage of the graphene sheets, which corresponds to a 7.2% enhancement of Jsc compared with solar cells without Al nanoparticles and graphene sheets. This achievement demonstrates that textured Al nanoparticle/graphene-enhanced screen-printed solar cells can exceed the light-trapping limits of plasmonic photovoltaic devices.

The increase in EQE for the Al nanoparticle/graphene-enhanced solar cell is demonstrated in Figure 4a. The results clearly demonstrate a substantial improvement in broadband EQE by the integration of Al nanoparticles and wrinkle-like graphene sheets, which is consistent with the all-band absorption enhancement between 300 nm and 1200 nm, as shown in Figure 4b. The textured solar cell with Al nanoparticles exhibits a significantly increased broadband absorption between 300 nm and 1100 nm, which is caused by the effective light trapping of Al nanoparticles. The integration of wrinkle-like graphene sheets can further increase cell absorption near the wavelengths of 500, 900 and 1100 nm, which provide all-band absorption enhancements in the solar cells.

(a) EQE curves for screen-printed solar cells (black) and Al nanoparticle/graphene-enhanced screen-printed solar cells (red). The surface coverage for Al nanoparticles and graphene sheets was 10%; (b) The absorption enhancement of screen-printed solar cells through the integration of 100 nm Al nanoparticles and wrinkle-like graphene sheets (red, compared with bare cells), the absorption enhancement of screen-printed solar cells through the integration of 100 nm Al nanoparticles (purple, compared with bare cells), and the absorption enhancement of Al nanoparticle-enhanced screen-printed solar cells through the integration of wrinkle-like graphene sheets (blue, compared with Al-enhanced cells). EQE, external quantum efficiency.

Conclusions

For the first time, Al nanoparticle-enhanced single crystalline silicon solar cells were experimentally fabricated using an innovative and modified thermal evaporation method. A maximum gain of 6.3% in the Jsc was achieved for the textured screen-printed solar cells, due to the broadband absorption enhancement from the light scattering of Al nanoparticles. We determined that wrinkle-like graphene sheets synthesized by the wet chemical method exhibit absorption peaks at long wavelength ranges due to the bend carbon layers. A photocurrent enhancement is generated from the integration of the graphene sheets in the Al nanoparticle-enhanced solar cells. This method increased the Jsc of the textured screen-printed solar cells by 7.2% compared with the Jsc of the solar cell without Al nanoparticles and graphene sheets. The realization of Al nanoparticle/graphene-enhanced solar cells provides a pathway to exceed the limit of plasmonic light trapping with parasitic absorption and to fabricate the screen-printed solar cell with 19.54% conversion efficiency. Future investigations will focus on tailoring the wavelengths of light trapping materials to achieve enhanced solar cell performance.

References

Atwater HA, Polman A . Plasmonics for improved photovoltaic devices. Nat Mater 2010; 9: 205–213.

Ferry VE, Munday JN, Atwater HA . Design considerations for plasmonic photovoltaics. Adv Mater 2010; 22: 4794–4808.

Beck FJ, Mokkapati S, Catchpole KR . Light trapping with plasmonic particles: beyond the dipole model. Opt Express 2011; 19: 25230–25241.

Fahim NF, Ouyang Z, Jia BH, Zhang YN, Shi ZR et al. Enhanced photocurrent in crystalline silicon solar cells by hybrid plasmonic antireflection coatings. Appl Phys Lett 2012; 101: 261102.

Gu M, Ouyang Z, Jia BH, Zhang YN, Shi ZR . Nanoplasmonics: a frontier of photovoltaic solar cells. Nanophotonics 2012; 1: 235–248.

Ouyang Z, Pillai S, Beck F, Kunz O, Varlamov F et al. Effective light trapping in polycrystalline silicon thin-film solar cells by means of rear localized surface plasmons. Appl Phys Lett 2010; 96: 261109.

Fahim NF, Ouyang Z, Zhang YN, Jia BH, Shi ZR et al. Efficiency enhancement of screen-printed multicrystalline silicon solar cells by integrating gold nanoparticles via a dip coating process. Opt Mater Express 2012; 2: 190–204.

Schaadt DM, Feng B, Yu ET . Enhanced semiconductor optical absorption via surface plasmon excitation in metal nanoparticles. Appl Phys Lett 2005; 86: 063106.

Derkacs D, Lim SH, Matheu P, Mar W, Yu ET . Improved performance of amorphous silicon solar cells via scattering from surface plasmon polaritons in nearby metallic nanoparticles. Appl Phys Lett 2006; 89: 093103.

Wu JL, Chen FC, Hsiao YS, Chien FC, Chen P et al. Surface plasmonic effects of metallic nanoparticles on the performance of polymer bulk heterojunction solar cells. ACS Nano 2011; 5: 959–967.

Chen X, Jia BH, Saha JK, Cai BY, Stokes N et al. Broadband enhancement in thin-film amorphous silicon solar cells enabled by nucleated silver nanoparticles. Nano Lett 2012; 12: 2187–2192.

Zhang YN, Ouyang Z, Stokes N, Jia BH, Shi ZR et al. Low cost and high performance Al nanoparticles for broadband light trapping in Si wafer solar cells Appl Phys Lett 2012; 100: 151101.

Dai H, Li MC, Li YF, Yu H, Bai F et al. Effective light trapping enhancement by plasmonic Ag nanoparticles on silicon pyramid surface. Opt Express 2012; 20: A502–A509.

Fahim NF, Jia BH, Shi ZR, Gu M . Simultaneous broadband light trapping and fill factor enhancement in crystalline silicon solar cells induced by Ag nanoparticles and nanoshells. Opt Express 2012; 20: A694–A705.

Catchpole KR, Polman A . Design principles for particle plasmon enhanced solar cells. Appl Phys Lett 2008; 93: 191113.

Lassiter JB, Sobhani H, Fan JA, Kundu J, Capasso F et al. Fano resonances in plasmonic nanoclusters: geometrical and chemical tunability. Nano Lett 2010; 10: 3184–3189.

Temple TL, Mahanama GD, Reehal HS, Bagnall DM . Influence of localized surface plasmon excitation in silver nanoparticles on the performance of silicon solar cells. Sol Energy Mater Sol Cells 2009; 93: 1978–1985.

Nair RR, Blake P, Grigorenko AN, Novoselov KS, Booth TJ et al. Fine structure constant defines visual transparency of graphene. Science 2008; 320: 1308.

Chen X, Jia BH, Saha JK, Stocks N, Qiao Q et al. Strong broadband scattering of anisotropic plasmonic nanoparticles synthesized by controllable growth: effects of lumpy morphology. Opt Mater Express 2013; 3: 27–34.

Hummers WS, Offeman RE . Preparation of graphitic oxide. J Am Chem Soc 1958; 80: 1339.

Geng JX, Liu LJ, Yang SB, Youn SC, Kim DW et al. A simple approach for preparing transparent conductive graphene films using the controlled chemical reduction of exfoliated graphene oxide in an aqueous suspension. J Phys Chem C 2010; 114: 14433–14440.

Yang HB, Guai GH, Guo CX, Song QL, Jiang SP et al. NiO/graphene composite for enhanced charge separation and collection in p-type dye sensitized solar cell. J Phys Chem C 2011; 115: 12209–12215.

de Arco LG, Zhang Y, Schlenker CW, Ryu K, Thompson ME et al. Continuous, highly flexible, and transparent graphene films by chemical vapor deposition for organic photovoltaics. ACS Nano 2010; 4: 2865–2873.

Kymakis E, Stratakis E, Stylianakis MM, Koudoumas E, Fotakis C . Spin coated graphene films as the transparent electrode in organic photovoltaic devices. Thin Solid Films 2011; 520: 1238–1241.

Ausman KD, Piner R, Lourie O, Ruoff RS . Organic solvent dispersions of single-walled carbon nanotubes: pristine nanotubes. J Phys Chem B 2000; 104: 8911–8915.

Akimov YA, Koh WS, Ostrikov K . Enhancement of optical absorption in thin-film solar cells through the excitation of higher-order nanoparticle plasmon modes. Opt Express 2009; 17: 10195–10205.

Campos-Delgado J, Romo-Herrera JM, Jia XT, Cullen DA, Muramatsu H et al. Bulk production of a new form of sp2 carbon: crystalline graphene nanoribbons. Nano Lett 2008; 8: 2773–2778.

Liu WW, Yan XB, Lang JW, Peng C, Xue QJ . Flexible and conductive nanocomposite electrode based on graphene sheets and cotton cloth for supercapacitor. J Mater Chem 2012; 22: 17245–17253.

Liu Y, Gao L, Sun J, Wang Y, Zhang J . Stable Nafion-functionalized graphene dispersions for transparent conducting films. Nanotechnology 2009; 20: 465605.

Sun SR, Gao L, Liu YQ . Enhanced dye-sensitized solar cell using graphene-TiO2 photoanode prepared by heterogeneous coagulation. Appl Phys Lett 2010; 96: 083113.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the technical support from the Victoria-Suntech Advanced Solar Facility established under the Victoria Science Agenda scheme of the Victorian Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Note: Supplementary information for this article can be found on Light: Science & Applications' website .

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Jia, B., Zhang, Y. et al. Exceeding the limit of plasmonic light trapping in textured screen-printed solar cells using Al nanoparticles and wrinkle-like graphene sheets. Light Sci Appl 2, e92 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2013.48

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2013.48

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Graphene oxide for photonics, electronics and optoelectronics

Nature Reviews Chemistry (2023)

-

Recent Progress of Surface Plasmon–Enhanced Light Trapping in GaAs Thin-Film Solar Cells

Plasmonics (2023)

-

Solar cell design using graphene-based hollow nano-pillars

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Structural variations during aging of the particles synthesized by laser ablation of copper in water

Applied Physics A (2019)

-

Review and assessment of photovoltaic performance of graphene/Si heterojunction solar cells

Journal of Materials Science (2019)