Abstract

Objective:

Can a comprehensive, explicitly directive evidence-based guideline for all therapies that might affect the major morbidities of very low-birth-weight (VLBW) infants help a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) further improve generally favorable morbidity rates? Can Antifragility principles of provider adaptive growth from stressors, enhanced infant risk assessment and adherence to effective therapies minimize unproven treatments and reduce all morbidities?

Study Design:

Prospectively planned observational trial in VLBW infants: control group born October 2011 to September 2013 and study group October 2013 to September 2015. Multi-disciplinary evidence-based review assigned all NICU treatments into one of four distinct categories: (1) always employ this therapy for VLBW infants, (2) never use this therapy, (3) employ this questionable therapy thoughtfully, only in certain circumstances and (4) this therapy has insufficient evidence of efficacy and safety. Extensive staff education emphasized evidence-based potentially better practice (PBP) selection with compliance checks, appreciation of intertwined co-morbidities and prioritizing infant risk reduction strategies.

Results:

Control included 221 infants, mean (s.d.) age 29 (2.6) weeks, birth weight 1129 (257) g and Study included 197 infants, 29 (2.7) weeks, 1093 (292) g. One hundred and four distinct therapies were placed into categories 1 to 4, with 32 specific compliance checks. Overall mean compliance with the process checks during the second era was 70%, high: 100% (exclusive breast milk use), low: 24% (correct pulse oximetry alarm settings). Morbidity and mortality rates did not significantly change during the second era.

Conclusions:

In our NICU with favorable morbidity rates, an expanded effort using a comprehensive therapy guideline for VLBW infants did not further improve outcomes. We need deeper understanding of continuous quality improvement (CQI) fundamentals, therapy compliance, co-morbidity relationships and enhanced sensitivity of risk assessment. Our innovative Antifragility PBP guideline could be useful to other NICUs seeking improvement in VLBW infant morbidities, as we offer a reasoned and concise template of a broad array of therapies categorized efficiently for transparency and review, designed to enhance responsible CQI decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Open sharing of continuous quality improvement (CQI) experience is crucial, even when projects are not successful, because learning accelerates at the intersection of careful documentation and transparency. The reduction of certain neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) morbidities driven by evidence-based principles of CQI is encouraging.1, 2 The Vermont Oxford Network (VON) has championed multidisciplinary collaboration and potentially better practice (PBP) sharing within its membership achieving significant reductions over the past 25 years in any late infection and retinopathy of prematurity in very low-birth-weight (VLBW) infants.1 VON CQI tools are particularly enticing for NICUs with comparatively high morbidity rates, because adopting fundamental CQI techniques reliably reduces unfavorable rates to at least average percentiles. Our next challenge is to develop dependable CQI blueprints that guide sustained multiple morbidity reduction to top quartile percentiles, thus far an elusive goal.3, 4

What about NICUs experienced with traditional evidence-based medicine (EBM) and CQI techniques that already have favorably low morbidity rates? How can these NICUs sustain progress and how can the intricate relationships among potentially competing co-morbidities be better understood? For example, which NICUs reliably minimize chronic lung disease and retinopathy of prematurity, while also consistently reducing the burden of any late infection, necrotizing enterocolitis and intraventricular hemorrhage, and how exactly is this done? Despite impressive progress in NICU CQI, there is currently no published detailed CQI instructional guideline that reliably leads to sustained, multiple morbidity reduction.

Antifragility is the ability of adaptive individuals or organizations to absorb, integrate and not just withstand stressors but actually improve from challenge—hormesis. As described by Taleb5, a wide swath of human endeavors throughout history strongly suggests that successful people and groups share a common feature—the adroit ability to weigh the upside and downside of critical decisions, with an embedded appreciation of the highly nonlinear relationship of many cause-and-effect connections. The conception of ‘Black Swan’ events by Taleb5 (unpredicted, rare cataclysms that immediately alter accepted paradigms) and the pivotal moral nature of Antifragility, that is, if I have skin-in-the-game, and cannot transfer that risk to you, then we make adaptive decisions together thoughtfully, are valuable insights we think are relevant to EBM and NICU CQI.

The purpose of this study is to share how our NICU, an experienced 20-year participant in formal local and national CQI activities, but puzzled and frustrated by a lack of sustained improvement, has attempted to excel by understanding Antifragility and infusing its principles into our daily EBM decision-making. We provide for scrutiny the following: (a) an unusually detailed template of PBP classification for all the major VLBW infant morbidities, (b) specific bedside compliance measurements for each morbidity typically scarce in CQI reports, (c) a comprehensive morbidity rate report and (d) speculation regarding the challenges and possible limitations inherent to current CQI methodology.

Methods

The Providence Health System institutional review board approved this investigation. Providence St. Vincent Medical Center (PSVMC) has a Level 3 NICU and this was a prospectively planned observational trial using a historical control group. Our population included all inborn VLBW infants 401 to 1500 g, delivered 1 October 2011 to 30 September 2013 (Era 1 Control Group), compared with those delivered 1 October 2013 to 30 September 2015 (Era 2 Antifragility Group). The PSVMC NICU has been a member of the VON since 1995 and has participated in many organized CQI activities related to the VON NICQ collaborative.6

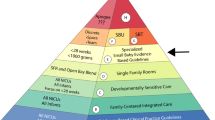

In January 2013, we began an ambitious project: (a) review our history of CQI activities and the year-to-year VLBW infant mortality and morbidity rates so that everyone understood our early success (‘low-hanging fruit’) followed by variable morbidity improvement stagnation (‘high or hidden fruit’); (b) introduce the principles of Antifragility, hormesis, risk assessment and complex cause-and-effect relationships; (c) carefully review every possible therapy that might be used in our NICU to prevent or treat one or more of the nine major morbidities of prematurity and conduct comprehensive literature reviews. We then (d) assigned by consensus every therapy to one of four ‘Antifragility Categories’—(1) do this virtually every time for every VLBW infant; (2) never do this; (3) apply this therapy in certain circumstances, but thoughtfully with careful upside/downside considerations; and (4) this therapy is of uncertain efficacy and safety so optimal use is unknown—(e) selected two or more compliance checks for each of the nine morbidities; and (f) committed to an every 3-month review for 2 years of VLBW infant outcomes, adherence with the compliance checks and feedback to all NICU staff. A PBP was defined as an Antifragility category 1 or category 3.

Evidence-based review of NICU therapies was facilitated by subdividing into the nine major VLBW infant morbidities (chronic lung disease, any late infection, grade 3 to 4 intraventricular hemorrhage, periventricular leukomalacia, stage 3 to 4 retinopathy of prematurity, necrotizing enterocolitis, focal intestinal perforation, patent ductus arteriosus and discharge weight <10th percentile) using the VON definitions.7 Each of the nine morbidities was assigned to one PSVMC neonatologist who led a comprehensive review of the published literature and categorized all potential therapies into the antifragility categories described in ‘c’ and ‘d’. Our anchor—‘Has this therapy been rigorously shown to safely and effectively prevent or treat Morbidity X?’ If not, is it unsafe and ineffective, or was there an exceptional, reasoned indication for the practice, or do we simply not know? This Antifragility consensus PBP guideline was also circulated to six national experts in NICU CQI for review and comments.

For 2 months before our ‘go-live’ date of 1 October 2013, we thoroughly discussed the Antifragility project with our NICU staff using multiple forums (bedside rounds, conferences, email alerts and posters). Multi-pronged CQI projects often have inexact implementation dates and we were aware that our NICU historically did not have comprehensive compliance data for many of our common therapies. To address this issue we underscored that detailed, formal PBP compliance data would begin 1 October 2013, and that this exact start date would motivate staff to follow the Antifragility PBP guidelines. We emphasized the complex nature of intertwined co-morbidities, the limited number of truly safe, effective therapies, the need for constant process and outcomes review, the largely unmeasured cultural and human factors that affect CQI, the acceptance of personal and group responsibility for the risk and uncertainty of NICU care and transparent decision-making.

For between era comparisons, χ2- or Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical variables and t-test or Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test were used for continuous variables. The 2014 entire VON outcomes were used as benchmarks to evaluate the results of the Era 2 Antifragility Group, so the exact binomial test was used for categorical variables and t-test for the length of stay. Statistical analysis was performed using R 3.1.0 statistical program (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Table 1 shows no significant differences in the demographic descriptors comparing the two eras (except fewer Era 2 multiple births). Our NICU’s VON risk adjusters in Table 1, as well as gestational age and birth weight distribution are similar to the entire VON (data available at Nightingale Electronic Reporting System). Table 2 summarizes the ‘Antifragility Potentially Better Practice Schema’. The nine major morbidities and all 104 therapies PSVMC considered as possible treatments were placed into one of four distinct categories. Table 3 lists our 32 consensus choices for detailed compliance checks, at least two for each morbidity, acknowledging that limitations of time, resources and understanding of cause-and-effect necessarily led to practical measurements.

Overall compliance with the process checks (averaged within each of the 32 categories, then each category weighted equally) was 70%, from a high of 100% (exclusive breast milk use, no milk thickeners, head of bed elevated, no concurrent use of prostaglandin synthase inhibitors and corticosteroids, and daily use of total parenteral nutrition calculator), to a low of 24% (correct pulse oximeter alarm settings). Table 4 lists the PSVMC mortality and morbidity rates in our two study eras and, for comparison, the 2014 entire VON. Eight of the nine major morbidity rates trended lower in our Era 2 Antifragility Group compared with the VON, three of them significantly. Mortality also trended lower at PSVMC and our total length of stay in survivors was significantly shorter than the VON. There were no significant changes in any outcome comparing the PSVMC Era 1 Control Group with the Era 2 Antifragility Group.

Discussion

Proven EBM methodology that reduces all major VLBW infant morbidities to sustained low rates has proven elusive for the vast majority of NICUs.1, 2, 3, 4 We have provided a transparent, concise yet broad, EBM guideline that contains most potential therapies thought to reduce the burden of the nine major VLBW infant morbidities. A succinct four category PBP classification schema (Table 2 and updated in Supplementary Table S1) and detailed compliance checks (Table 3 and updated in Supplementary Table S2) has, to our knowledge, never been published. Even when CQI projects are disappointing, publishing well-documented experience disseminates valuable experience, an essential goal encouraged by EBM experts.8, 9, 10, 11

We believe the principles of Antifragility—an interpretation of human cognition and behavior broadly evident in modern history—adds insight to how neonatologists and NICU staff make decisions, for better or worse.5 Antifragility emphasizes hormesis (adapting and improving from stressors) and appreciating the difference between uncertainty and risk. Uncertainty means you do not know what will happen, risk is the product of harm and the chance it will happen. Unlike families, NICU providers may conflate uncertainty and risk, too easily transferring risk (our vulnerability and responsibility) to the group and inevitably to the infant.12 Table 3 (compliance data that is scarce in many CQI reports) suggests the poorest adherence with PBPs largely resided among those activities in which risk could be transferred from the individual provider to the group and/or the baby.

Table 3 lists examples of possible risk transfer that undermine NICU CQI as follows: (a) it may be easier for a neonatologist to intubate a premature infant rather than try nasal continuous positive airway pressure with all the attendant patience, skill and serial exams required, (b) nurses widen saturation targets to lessen annoying and disruptive pulse oximeter alarms, or to ‘keep the baby pink’, (c) to stabilize newborns’ immediate respiratory needs neonatologists may mechanically over-ventilate, (d) antibiotics are started and maintained beyond 48 h despite negative cultures, and (e) the patent ductus arteriosus is treated early without objective evidence of shunt harm.

We did not demonstrate significant reduction in the major VLBW infant morbidities; thus, why should our proposed CQI model be reasonable to consider? First, we acknowledge the limitations of our CQI efforts as follows: (a) most NICU therapies are not supported by the strong Level 1 evidence of randomized, controlled trials (Table 2) so we would not necessarily expect sustained morbidity reduction to low rates, (b) there was variable compliance with our PBPs, just 70% overall, range 24 to 100% (Table 3), (c) time and resource constraints, and (d) uneven understanding of EBM and CQI principles.11 In addition, our NICU morbidity rates in the Era 1 Control Group were generally favorable (Table 4), for example, any late infection (4%) and grade 3 to 4 intraventricular hemorrhage (2%); thus, further improvement is not easily guided by customary means.

It may be unrealistic to think we can reduce certain morbidities similar to stage 3 to 4 retinopathy of prematurity, any late infection or periventricular leukomalacia from recent low rates to near zero. So much pathophysiology is unclear with these morbidities that it is unlikely traditional CQI methodology alone will be successful. Nevertheless, there are multiple sensible strategies to reduce some major morbidities, PBPs of little risk to the NICU provider, for example, hand washing, breast milk, fewer ventilator days and limiting unnecessary medications.1, 2, 3, 4

Although we categorized 104 distinct NICU VLBW infant therapies into the four Antifragility PBP categories, creating a user-friendly EBM guideline (Table 2), there are possibly other effective therapies not listed and any PBP prioritization needs to be updated as more evidence accumulates (see Supplementary Table 1). We selected 32 distinct compliance checks by consensus and practicality; not only was compliance considerably <100% with some PBPs (Table 3), but others were not formally monitored, for example, effects of placental transfusion.13 Many PBPs are proposed for VLBW infants, but the variable application and effects are often not rigorously quantified, making it exceedingly difficult for NICUs to confidently know why they are improving (or not). An observational trial similar to ours is limited by possible unmeasured practice changes and unforeseen differences in the VLBW infants between the two eras.14, 15

Our CQI experience also suggests a ‘tragedy of the commons’ embedded within group dynamics—individual providers acting independently can repeatedly make decisions that reduce their own risk or inconvenience at the expense of group goals and the infant’s best interests. Many modern day problems not only resist purely technical approaches, but are exacerbated by short-term quasi-solutions to complexities that inevitably create even more perplexing residual difficulties, which are exceedingly recalcitrant and costly to solve.16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Recognizing this, authorities such as Davidoff21 believe CQI is fundamentally a moral activity; improvement science should be on par with beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy and justice. This is congruent with Antifragility principles: how do we foster a moral CQI symbiosis of (a) knowing what to do, (b) how to do it reliably, (c) family preference and (d) societal priorities.22, 23, 24, 25

We continue our study in a third 2-year era (2016–17) with both an updated PBP guideline and an expanded compliance checklist (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). Perceptively evaluating the favorable versus unfavorable asymmetry inherent in virtually every NICU decision embodies Antifragility; every medical intervention is an amalgam of uncertainty, risk, preference and cost—variables exceedingly challenging to measure.

References

Horbar JD, Carpenter JH, Badger GJ, Kenny MJ, Soll RF, Morrow KA et al. Mortality and neonatal morbidity among infants 501 to 1500 grams from 2000 to 2009. Pediatrics 2012; 129: 1019–1026.

Ellsbury DL, Clark RH, Ursprung R, Handler DL, Dodd ED, Spitzer AR . A multifaceted approach to improving outcomes in the NICU: the Pediatrix 100,000 babies campaign. Pediatrics 2016; 137 (4): e20150389.

Kaempf JW, Zupancic JAF, Wang L, Grunkemeier GL . A risk-adjusted, composite outcomes score and resource utilization metrics for very low-birth-weight infants. JAMA Pediatrics 2015; 169 (5): 459–465.

Dukhovny D, Pursley DM, Kirpalani HM, Horbar JH, Zupancic JAF . Evidence, quality, and waste: solving the value equation in neonatology. Pediatrics 2016; 137 (3): e20150312.

Taleb N . Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder. Random House: New York, 2012.

Horbar JD, Soll RF, Edwards WH . The Vermont Oxford Network: a community of practice. Clin Perinatol 2010; 37 (1): 29–47.

Vermont Oxford Network Database Manual of Operations. Release 19.0. Vermont Oxford Network: Burlington, 2014.

Berwick DM . The science of improvement. JAMA 2008; 299 (10): 1182–1184.

Van Cleave J, Dougherty D, Perrin JM . Strategies for addressing barriers to publishing pediatric quality improvement research. Pediatrics 2011; 128 (3): e678–e686.

Chassin MR, Loeb JM, Schmaltz SP, Wachter RM . Accountability measures – using measurement to promote quality improvement. N Engl J Med 2010; 363 (7): 683–688.

Casarett D . The science of choosing wisely – overcoming the therapeutic illusion. N Engl J Med 2016; 374 (13): 1203–1205.

Ralston SL, Schroeder AR . Doing more vs doing good: aligning our ethical principles from the personal to the societal. JAMA Pediatrics 2015; 169 (12): 1085–1086.

Kaempf JW, Tomlinson MW, Kaempf AJ, YingXing Wu, Wang L, Tipping N et al. Delayed umbilical cord clamping in premature infants. Ob Gyn 2012; 120 (2): 325–330.

Profit J, Gould JB, Bennett M, Goldstein BA, Draper D, Phibbs CS et al. The association of level of care with NICU quality. Pediatrics 2016; 137 (3): e20144210.

Blumenthal D . Better health care: a way forward. JAMA 2016; 315 (3): 1333–1334.

Hardin G . The tragedy of the commons. Science 1968; 162 (3859): 1243–1248.

Schwartz E . Overskill: The Decline of Technology in Modern Civilization. Quadrangle Books: Chicago, 1971.

Callahan D . False Hopes: Overcoming the Obstacles to a Sustainable, Affordable Medicine. Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, New Jersey, 1999.

Silverman WA . Human Experimentation: A Guided Step into the Unknown. Oxford University Press: Oxford, England, 1985.

Gray J . Straw Dogs. Granta Publications: London, England, 2002.

Davidoff F . Systems of service: reflections on the moral foundations of improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2011; 20: i5–i10.

Kaempf JW, Tomlinson MW, Tuohey J . Extremely premature birth and the choice of neonatal intensive care versus palliative comfort care: an 18-year single-center experience. J Perinatol 2016; 36: 190–195.

Kelly MP, Heath I, Howick J, Greenhalgh T . The importance of values in evidence-based medicine. BMC Med Ethics 2015; 16 (69): 1–8.

Wilkinson D, Chalmers I, Cruz M, Tarnow-Mordi W . Dealing with the unknown: reducing the proportion of unvalidated treatments offered to children. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2015; 100 (3): F190–F192.

Lefkowitz W, Jefferson TC . Medicine at the limits of evidence: the fundamental limitation of the randomized clinical trial and the end of equipoise. J Perinatol 2014; 34: 249–251.

Acknowledgements

This investigation was supported by the Providence Health and Services Foundation (Portland, OR) and Northwest Newborn Specialists, PC (Portland, OR). The sponsors had no role in the design or conduct of the study. We thank the entire PSVMC Antifragility Team including Jody Bellant, Sara Clark, Kati Knudsen, Jennifer Niemeyer, Yvette Rice-Rosenthal, Kandace Ryan and Melissa Stawarz for their many contributions to this team effort.

Author contributions

The principal investigator JWK, MD, had full access to the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data analysis. The source of the data was our PSVMC comprehensive NICU database (NICPOP) and collection tools, as well as the Vermont Oxford Database accessible at the Nightingale Electronic Internet Reporting System. JWK was responsible for the original conception and design of the study and drafted the first and final versions of the manuscript. Co-authors NMS, SR, CN, MF, LW and NT assisted in implementation of the project, critical review of the manuscript at each step, all data analysis and participated in the manuscript formulation and final revision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Journal of Perinatology website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kaempf, J., Schmidt, N., Rogers, S. et al. The quest for sustained multiple morbidity reduction in very low-birth-weight infants: the Antifragility project. J Perinatol 37, 740–746 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2017.7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2017.7

This article is cited by

-

Paving New Roads Towards Biodiversity-Based Drug Development in Brazil: Lessons from the Past and Future Perspectives

Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia (2021)