Abstract

In addition to the cyanobacterial N2-fixers (diazotrophs), there is a high nifH gene diversity of non-cyanobacterial groups present in marine environments, yet quantitative information about these groups is scarce. N2 fixation potential (nifH gene expression), diversity and distributions of the uncultivated diazotroph phylotype γ-24774A11, a putative gammaproteobacterium, were investigated in the western South Pacific Ocean. γ-24774A11 gene copies correlated positively with diazotrophic cyanobacteria, temperature, dissolved organic carbon and ambient O2 saturation, and negatively with depth, chlorophyll a and nutrients, suggesting that carbon supply, access to light or inhibitory effects of DIN may control γ-24774A11 abundances. Maximum nifH gene-copy abundance was 2 × 104 l−1, two orders of magnitude less than that for diazotrophic cyanobacteria, while the median γ-24774A11 abundance, 8 × 102 l−1, was greater than that for the UCYN-A cyanobacteria, suggesting a more homogeneous distribution in surface waters. The abundance of nifH transcripts by γ-24774A11 was greater during the night than during the day, and the transcripts generally ranged from 0–7%, but were up to 26% of all nifH transcripts at each station. The ubiquitous presence and low variability of γ-24774A11 abundances across tropical and subtropical oceans, combined with the consistent nifH expression reported in this study, suggest that γ-24774A11 could be one of the most important heterotrophic (or photoheterotrophic) diazotrophs and may need to be considered in future N budget estimates and models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biological nitrogen (N2) fixation, the reduction of atmospheric N2 gas to ammonium, is a process performed only by certain microorganisms (diazotrophs). This bioavailable N is an important source of N that supports primary production in oligotrophic marine ecosystems (Karl et al., 1997), where N availability often limits phytoplankton growth (Graziano et al., 1996; Mills et al., 2004). Rate measurements and geochemical estimates suggest N inputs via N2 fixation are much smaller than the N loss processes through denitrification (including anaerobic ammonium oxidation) (Mahaffey et al., 2005). A better understanding of the identity, distributions and activity of microorganisms contributing to N2 fixation in the oceans is necessary in order to balance the oceanic N budget (Zehr and Kudela, 2011).

The diversity and abundances of diazotrophs in the oceans have been studied using sequence diversity and abundances of the nifH gene, which encodes a key structural protein of the nitrogenase enzyme that catalyzes the N2 fixation reaction (Zehr and Paerl, 1998). The most significant N2-fixing microorganisms in the ocean are thought to be the cyanobacteria Trichodesmium (Capone et al., 1997), symbiotic and free-living unicellular cyanobacteria (UCYN, including Crocosphaera) (Zehr et al., 2001; Montoya et al., 2004), and filamentous symbionts (of the order Nostocales) that associate with diatoms (Villareal, 1994; Carpenter et al., 1999). Molecular surveys from various marine environments have also recovered a high diversity of nifH genes that cluster with non-cyanobacterial bacteria (Zehr et al., 2003b) in surface waters and even below the epipelagic zone in the open ocean (Langlois et al., 2005; Hewson et al., 2007; Hamersley et al., 2011; Halm et al., 2012). The diazotrophic bacteria that have been obtained from open ocean epipelagic seawater cluster with a wide range of bacterial groups, including alpha-, beta-, gamma- and deltaproteobacteria and Firmicutes (Zehr et al., 1998, 2003b). A majority of the diverse heterotrophic communities detected at the DNA level in marine environments have not been detected in mRNA (Omoregie et al., 2004; Man-Aharonovich et al., 2007; Short and Zehr, 2007), thus the contribution of nifH gene-containing heterotrophic bacteria to the N cycle in oceanic environments remains unclear. These groups potentially contribute to the N2 fixation activity that is often reported in the <10 μm small size fraction (Staal et al., 2007a; Bonnet et al., 2009; Benavides et al., 2011). A small number of heterotrophic bacterial sequence types have been repeatedly found in open ocean clone libraries, which includes a gammaproteobacteria-affiliated group that we here call γ-24774A11 based on a nifH sequence recovered from the South China Sea (Moisander et al., 2008). It is not known whether it is free-living or forming symbioses such as the diazotrophic cyanobacterium UCYN-A (Candidatus Atelocyanobacterium thalassa) (Thompson et al., 2012). Different gammaproteobacterial nifH sequences have been recovered from tropical and subtropical (Zehr et al., 1998) to polar (Diez et al., 2012) oceans. γ-24774A11 appears to have a broad geographic distribution, including the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, Mediterranean Sea, Red Sea, Arabian Sea and South China Sea, and its nifH transcripts have been detected in several studies (Falcon et al., 2004; Bird et al., 2005; Church et al., 2005; Bombar et al., 2011; Turk et al., 2011). The frequent observations and nifH transcription indicate that this group may have a more significant role in oceanic N2 fixation than some of the other nifH gene-containing heterotrophic bacteria. To date, the γ-24774A11 phylotype remains uncultivated and no other genetic information besides the nifH sequence is available from this bacterium. Its ecophysiology, genetic potential, and contribution to oceanic N2 fixation are unknown.

Diurnal cycles in oceanic cyanobacterial diazotroph N2 fixation and nifH expression have been described, but data on diel patterns in nifH expression in heterotrophic diazotrophs are scarce. Diel patterns of N2 fixation activity in the marine cyanobacteria Trichodesmium, UCYN-A, and Crocosphaera watsonii have been reported, and while probably partially regulated by circadian rhythms (Chen et al., 1996), the cycles of nitrogenase activity are directly linked with access to energy supporting the enzyme and strategies for protection against inhibition by O2 (Postgate, 1990; Rabouille et al., 2006). The diel cycle in the marine filamentous cyanobacterium Trichodesmium is well characterized, with the majority of the N2 fixation occurring during the day (Staal et al., 2007b). The uncultivated UCYN-A, a heterotrophic cyanobacterium, has been thought to express nifH primarily during the day (Church et al., 2005) while peak nifH expression and N2 fixation of C. watsonii occurs during the night (Tuit et al., 2004; Shi et al., 2010). Although mRNA from heterotrophic bacterial groups has been detected in several studies, little information is available on spatial and temporal variability in nifH gene expression of non-cyanobacterial oceanic diazotrophs, particularly in natural conditions. Heterotrophs might be expected to also have a diel pattern, as they may be dependent upon light-generated photosynthate from phytoplankton, or may be dependent on supplementary light-driven energy, perhaps through proteorhodopsins.

In this study, we detected the γ-24774A11 nifH gene sequence cluster in the low-nutrient, low-chlorophyll waters of the western South Pacific Ocean. We investigated its diversity compared with other ocean regions, quantified abundances of the phylotype and determined day vs night nifH expression with respect to depth in the epipelagic waters. Comparisons of the day–night expression at nine stations across the region allowed us to determine the nifH expression diel pattern of this diazotroph. The results were compared with those for the major cyanobacterial groups, and the influence of environmental parameters was investigated. The information on diel variability in gene expression and distribution patterns in comparison with other diazotrophs further underscores the need to fully determine the importance of non-cyanobacterial diazotrophs in oceanic N2 fixation.

Materials and methods

Samples were collected onboard R/V Kilo Moana in March–April 2007 from Coral Sea, Australia (155°E, 15°S), moving southeast (to 160°E, 30°S), then returning back to New Caledonian and Fijian waters, reaching 170°W, 15°S. Samples were taken from 23 stations over 34 days (Figure 1).

The water column density structure, O2, and in situ fluorescence were determined from conductivity–temperature–depth profiles. Discrete samples were collected for extracted chlorophyll a, (Welschmeyer, 1994) nutrients (SRP, NO3−, NO2−) (Strickland and Parsons, 1972; Sakamoto et al., 1990; Karl and Tien, 1992; Zhang, 2000), dissolved organic carbon (DOC) (Carlson et al., 2004), total dissolved nitrogen (TN) (Walsh, 1989) and abundances of picoplankton (Zehr et al., 2008), from the same depths as those for determination of abundances and gene expression of diazotrophs. Methods are described elsewhere in detail (Moisander et al., 2010).

For DNA and environmental parameters, samples were collected from 8 depths between 0 and 175 m (Supplementary Table S1). Approximately 4.5 l of surface water was sequentially filtered through 10-μm (polycarbonate, Osmonics, Trevose, PA, USA) and 0.2-μm (Supor, Pall Gelman, Port Washington, NY, USA) filters. DNA was extracted using a modified Qiagen (Germantown, MD, USA) Plant kit protocol (Moisander et al., 2008). Abundances of γ-24774A11 were determined by the quantitative Taqman 5′-nuclease assay PCR (Supplementary Table S2) (Short and Zehr, 2005; Moisander et al., 2010). Data for abundances of four groups of diazotrophs (UCYN-A, C. watsonii, Trichodesmium spp. and filamentous cyanobacterial symbionts) are discussed elsewhere (Moisander et al., 2010) (Supplementary Table S1).

Nested PCR with degenerate nifH primers (Zehr and Turner, 2001) was used to create a nifH clone library, using previously reported amplification conditions (Moisander et al., 2008). Fourteen samples in which high γ-24774A11 abundances were recorded by quantitative PCR were chosen for clone libraries. In order to further address potential microdiversity, γ-24774A11-specific primers were designed. Flanking regions in the 24774A11 partial nifH sequence generated by the degenerate primer approach were targeted (Oligoperfect, Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). The primers (Supplementary Table S2) resulted in a product with an expected fragment length of 281 bp. The 24774A11-PCR cycling was initiated by 95°C for 2 min, followed by 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 56°C and 30 s at 72°C for 30 cycles and finally, 7 min at 72°C. Bands were excised, cloned into a pGEM-T (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) vector and sequenced at the UC Berkeley sequencing facility. If bands were observed in negative controls, they were sequenced. Sequences were trimmed using CLC Workbench (Aarhus, Denmark) and imported into a nifH database in ARB software (Ludwig et al., 2004). The sequences were aligned against an nifH database containing >23 000 sequences, originally aligned using a HMMER algorithm based on PFAM. Neighbor-joining trees were created for conceptually translated sequences using Kimura correction in ARB. The sequences from this study have GenBank accession numbers HQ229006-HQ229036 and KF619449-KF619537.

Expression of the nifH gene by γ-24774A11, UCYN-A, Crocosphaera and Trichodesmium were investigated by quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT–PCR). RNA samples were collected around midday (filtration time 1300–1530 hours) or midnight (filtration time 2140–3:40 hours) into acid-washed 4.5-l polycarbonate bottles using Niskin bottles from four depths in the euphotic layer, followed by filtration. Identical samples were collected at each time point and placed in a deck incubator for 12 h, then filtered during the opposite light phase. In few cases, holding in the incubator was not necessary, if sampling was conducted at the same station both during the day and night. RNA samples were filtered similarly to the DNA samples, and filters were placed in sterile tubes containing 350 μl RLT buffer (Qiagen RNeasy minikit) with 1% β-mercaptoethanol and ∼50 μl of a mixture of 0.1-mm and 0.5-mm diameter glass beads (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK, USA). Tubes were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

RNA was extracted using a modified RNeasy protocol. Samples were homogenized over two 2-min intervals (Mini-Beadbeater-96, BioSpec Products), with 1-min cooling on ice between bead beatings. Tubes were centrifuged at 8000 g for 2 min, filters were removed and tubes centrifuged again. The supernatants were transferred to new 2-mL tubes and 250 μl of 100% ethanol was added. RNA purification was then carried out according to the manufacturer’s protocol, including a 1-h on-column DNase digestion. Samples were eluted into 50 μl of RNase-free water and stored at −80 °C. RNA was reverse transcribed using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT–PCR (Invitrogen, Life Technologies), with 8 μl of RNA extract. Gene-specific reverse primers nif2 and nif3 (Zehr and Turner, 2001) were added at 5 pmol each. Negative control and no-qRT reactions were run for each sample using DEPC-treated water in place of the reverse transcriptase.

nifH gene expression was quantified using qRT–PCR assays targeting γ-24474A11 and four cyanobacterial diazotrophs (Supplementary Table S2). Expression by UCYN-A, Crocosphaera and γ-24774A11 was measured from 0.2-μm filters. Ten micrometer filters from daytime were assayed for Trichodesmium and heterocyst-forming diatom symbiont Richelia (Het-1). qPCR was conducted on RT and no-RT products for each sample using Applied Biosystems (ABI, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) 7500 Real-Time PCR system using 2 min at 50 °C followed by 45 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C. The 25-μL reactions consisted of 12.5 μl ABI TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix, 0.4 μM and 0.2μM final concentrations of primers and probe, respectively, 2 μl template and 8 μl water. Standards, consisting of eight 10-fold dilutions of linearized recombinant plasmids containing the relevant nifH targets (107-100 copies per reaction), were run on each plate. Standard curves were generated by linear regression of threshold cycle (Ct) vs log number of gene copies per reaction. Linear regression R2 values were ⩾0.99 for all standard curves. Amplification efficiencies were calculated using the equation E=10−1/m−1 where m is the slope of the standard curve. Efficiencies were >90% for all reactions. Standards, qRT and no-qRT samples were run in duplicate. Where amplification of no-qRT samples occurred, no-qRT gene-copy values were subtracted from qRT gene copies to correct for DNA contamination. Six to eight no template controls were run on each plate. Inhibition tests were carried out for each primer/probe set by delivering 2 μl each of 105 standard and cDNA sample to the same well and assessing the percent efficiency of the reaction in relation to the amplification of the standard alone (%efficiency=[1−(Ctinhibition−Ctstandard)/Ctstandard] × 100). Inhibition tests were conducted on a subset of eight cruise samples (station 5). The reaction efficiencies of inhibition tests were 97.3% or greater, thus, all samples were considered uninhibited. The limits of detection and quantification have been empirically determined to be 1 and 8 copies per reaction, respectively (data not shown). Amplifications falling below the limit of quantification were designated as detected but not quantifiable (DNQ), and as value '1' in the data.

Day and nighttime transcript abundances were compared by non-parametric paired tests (Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-ranks test) for each nifH phylotype (IBM SPSS Statistics). Relationship of the abundances to environmental parameters was analyzed by linear regression (IBM SPSS Statistics). Data distribution was improved by log transformation. Abundances of gene copies and transcripts in the water column (from 0 to 150 m and from 0 to 125 m, respectively) were calculated by numerical integration.

Results

Phylogenetic analysis showed that amplified nifH gene sequences contained cyanobacterial and non-cyanobacterial nifH genes. A nifH sequence that closely matched UCYN-A was recovered from nine samples (Figure 2). These sequences had a 100% identity to nifH in the published UCYN-A (Candidatus Atelocyanobacterium thalassa) genome (Tripp et al., 2010). Sequences were recovered with a 99% amino-acid identity with C. watsonii WH8501 and Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101, respectively. An additional nifH phylotype (clone 33523A05) was recovered that had 88% amino-acid sequence identity to the UCYN-A nifH sequence, and 96% amino-acid sequence identity to a sequence from the North Pacific Ocean (DQ821974). One additional sequence type fell within the cyanobacteria clade, and another sequence was obtained that fell in Cluster 3 (as defined by (Zehr et al., 2003b).

Gene sequences were recovered using the nested nifH PCR approach that fell within the non-cyanobacterial γ-24774A11 cluster (Figures 2 and 3). Each of these sequences had one or more amino-acid substitutions in comparison with γ-24774A1-like sequences from prior studies. A total of 88 sequences were obtained using the γ-24774A11-specific primers (Figure 3). The majority of these sequences (83 of 88) were from one phylotype that is identical to the original γ-24774A11 clone (Moisander et al., 2008). Five additional phylotypes were recovered that each differed by one amino acid over the 93 residue γ-24774A11 sequence (Figure 3).

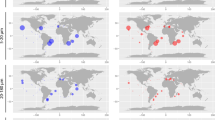

Neighbor-joining nifH phylogenetic tree for γ-24774A11 sequences from this study and other select studies. Sequences from this study include those obtained with γ-24774A11-specific primers. AO, Atlantic Ocean; MS, Mediterranean Sea; NPAC, North Pacific Ocean; Red Sea; SCS, South China Sea; SPOT, San Pedro Ocean Time-Series, Southern California.

Sequences were recovered from the negative PCR bands in the nested reactions, which were assumed to originate from PCR reagents (Zehr et al., 2003a). These sequences fell into their own cluster within alphaproteobacteria (Figure 2). We queried the nifH database with terms ‘PCR contaminant’ and ‘negative’ and included resulting sequences in our tree that were close matches with sequences we recovered from negative PCR bands. Previously reported negative control sequences, including Derxia sp. and Burkholderia sp. related sequences, were close to the sequences from the negative control reactions from this study.

γ-24774A11 distributions based on gene copies

Gene-copy abundances of γ-24774A11 varied from non-detectable to 2 × 105 gene copies l−1, and decreased below approximately 100 m depth (Figure 4). The maximum abundance of γ-24774A11 was 2 × 104 l−1 (at station 21) and thus two orders of magnitude lower than the maxima for UCYN-A, C. watsonii or Trichodesmium (Table 1). The median abundance across all samples, 8 × 102 copies l−1, however, was higher for γ-24774A11 than for UCYN-A or Trichodesmium (Table 1).

The abundances of γ-24774A11 were compared with those of other diazotrophs and to several environmental factors (Moisander et al., 2010) (Supplementary Table S1 and S3). There was a significant positive correlation between γ-24774A11 abundance and temperature, DOC and O2 saturation (P=0.000, n=156–173, Supplementary Table S3). O2 saturation varied from 61 to 102% in the 0–150 m surface layers, decreasing toward the DCM (Supplementary Figure S1), with no clear difference between day and night. The average euphotic zone depth was 100.6 m (±13.4) (Supplementary Table S1), when using 1% PAR from PAR in 5 m as the bottom of the euphotic layer. There was a negative correlation between γ-24774A11 abundance and depth, density, Sigma-T, NO3−, NO2−, SRP, TN, chlorophyll a and in vivo fluorescence (Supplementary Table S3). The abundance of γ-24774A11 was positively correlated with abundances of C. watsonii, Trichodesmium, Het-1 and Synechococcus cell numbers (Supplementary Table S3).

nifH expression

Unicellular diazotroph nifH gene expression was detected throughout the study area during the day and night (Supplementary Figure S2, Figure 5). Transcript abundances for γ-24774A11 were significantly higher at night than during the day (P=0.012, n=36, Wilcoxon matched-pair signed ranks test; Figure 5, Supplementary Figure S2, Table 2) and the same pattern was observed in C. watsonii (P=0.000, n=36). In contrast, transcript abundances were not significantly different between day and night for UCYN-A (P=NS, n=36). For all three unicellular diazotrophs, there was depth dependence of transcript abundances, with greatest abundances at the top 75–100 m of the water column (Supplementary Figure S2). Daytime nifH transcript abundances were up to 107 l−1 for Trichodesmium, and up to 103nifH transcripts per l−1 for Het-1 (Table 2).

Integrated transcript abundances for the entire upper water column (0–125 m) (transcripts m−2) were calculated and the proportions of diazotroph phylotypes in the community compared (Figures 5 and 6). Integrated transcript abundances were the most constant for γ-24774A11, with little variability among stations (Figure 5). Average integrated transcript abundances for UCYN-A (1 × 109 transcripts m−2 during the day and 3 × 108 m−2 at night) were 1–2 orders of magnitude greater than for γ-24774A11 (3 × 107 during the day and 8 × 107 at night), but had much greater variability (range from no detectable transcripts to 8 × 109 m−2 in UCYN-A, and from 6 × 104 to 3 × 108 m−2 in γ-24774A11). The abundances were greatest at the southernmost station 10 for UCYN-A, and at the mid-latitude station 6 for γ-24774A11. C. watsonii had the greatest transcript abundances of the three unicellular diazotrophs, with a maximum of 9 × 1010 transcripts m−2 at one of the northernmost stations (Stn 21) at night. The greatest transcript abundances for Trichodesmium and Het-1 were also detected at station 21 (Figures 5 and 6). For Het-1, the transcript abundance range (3 × 104 to 1.3 × 108 m−2) and average (4 × 107) during the day were very close to the values for γ-24774A11. UCYN-A comprised the majority of transcripts at the southernmost stations (8, 10 and 12) during the day and at station 10 during the night (Figure 6). Crocosphaera dominated transcripts at eight of the nine stations during the night and at two northwestern stations during the day (stations 4 and 6). Trichodesmium comprised the majority of daytime transcripts at four stations near the end of the transect. Het-1 formed 10% of transcripts at station 4 and less than 5% at all other stations during the day. The contribution of γ-24774A11 to the total transcript pool was between 0 and 7.4% of all transcripts, with the exception of station 4 during the day (24% of transcripts), and station 24 at night (26% of transcripts).

Discussion

Understanding the ecophysiology of the contributors to marine N2 fixation is the key for characterizing the controls and limitations of the oceanic N cycle. In spite of the known biogeochemical importance of N2 fixation, quantitative PCR studies suggest that diazotrophs in oceans are several orders of magnitude less abundant than dominant non-diazotrophic bacteria. Although diazotrophs could therefore be considered rare species, their unique functional niche is biogeochemically important in the marine ecosystem. Here we describe the diversity, abundances and N2 fixation gene diel expression in a non-cyanobacterial, gammaproteobacterial diazotroph in comparison with the major oceanic cyanobacterial diazotrophs.

Diversity

The results suggest that the γ-24774A11 nifH phylotype generally has a wide distribution in different oceans but that microdiversity is also important. The population in this study was dominated by one nifH phylotype that has been detected in several oceans, including the Atlantic (Langlois et al., 2005), South China Sea (Moisander et al., 2008; Bombar et al., 2011), North Pacific (Church et al., 2005) and Red Sea (Foster et al., 2009). Additional closely related phylotypes were detected in this study, in the North Pacific (Fong et al., 2008), Arabian Sea (Bird et al., 2005), Mediterranean Sea (Man-Aharonovich et al., 2007) and Southern California Bight (Hamersley et al., 2011).

The presence of nifH sequences as PCR reagent contaminants has been reported (Zehr et al., 2003a; Bostrom et al., 2007), and frequently the same groups within alphaproteobacteria have been reported as contaminants. We conclude that all sequences from the negative controls in this study that clustered closely with these alphaproteobacteria were indeed contaminating sequences. The nested nifH PCR protocol is known to be sensitive to reagent contamination (Zehr et al., 2003a), but the contaminants that appear in negative bands can be disregarded by sequencing them and removing these sequences from further analysis.

Abundance of γ-24774A11

The results suggest that the maximum abundances of the γ-24774A11 phylotype typically are lower than for the cyanobacterial diazotrophs (in this study they were two orders of magnitude lower). However, median abundances were higher than for UCYN-A and Trichodesmium, suggesting a more uniform distribution than of the cyanobacterial groups. The ubiquitous presence could suggest a broad tolerance for certain environmental conditions. For UCYN-A, the presence of conditions promoting the host organisms of this symbiotic cyanobacterium may have a key role, although they thus far remain unknown. Abundances of UCYN-A appear to be patchy both horizontally and vertically, likely following stratification of its eukaryotic hosts. Such stratification or patchiness is not evident with γ-24774A11 in this study, suggesting it is not dependent on a specific host, but may be a free-living heterotroph or photoheterotroph. Alternatively, it may be benefiting from associations with a host that is ubiquitous, or may be associated with particulate organic matter (Le Moal and Biegala, 2009). The greatest γ-24774A11 abundances were found in the <10-μm size fraction, suggesting that this diazotroph does not rely on a large host. However, the host may be small, or if the association with a host is loose, γ-24774A11 may dissociate during sample handling, as was found for UCYN-A (Thompson et al., 2012).

Influence of environmental conditions

N2 fixation, catalyzed by the nitrogenase enzyme, is strictly environmentally controlled. Importantly, the enzyme is destroyed by O2 (Fay, 1992), and the process requires a large amount of energy. Many ecological strategies have evolved among diazotrophs to avoid O2 inhibition. Cyanobacteria protect their nitrogenase from inhibition by O2 using either spatial (specialized cells such as heterocysts in Nostocales) or temporal (day–night variability) separation, while heterotrophic bacteria may use colony formation to protect cells from O2, allowing spatial separation of N2 fixation from extracellular O2 (Fay, 1992). A well-known example of an obligate aerobe in soils that fixes N2 aerobically by using respiratory protection is the gammaproteobacterium Azotobacter vinelandii, currently classified in Pseudomonadaceae (Rediers et al., 2004). In this study, O2 availability did not negatively control γ-24774A11 abundances or nifH expression, suggesting this bacterium may use respiratory protection or its nitrogenase may be protected through low O2 microzones in association with organic matter or a host organism. The positive correlation between abundances of γ-24774A11 and O2 could be due to co-variation of O2 with another controlling factor such as energy from bioavailable DOC or light. Unlimited access to energy in cyanobacteria is thought to make them superior to heterotrophic bacteria in terms of using N2 fixation to support growth (Postgate, 1990), and thus far, all of the known key open ocean oligotrophic diazotrophs that are active are cyanobacteria. While some heterotrophic bacteria can fix N2 in anaerobic or aerobic conditions, the organisms need to consume large amounts of carbon to obtain energy. Carbon is known to be an important growth-limiting factor for oceanic heterotrophic bacteria (Kirchman et al., 2000; Thingstad et al., 2008). We speculate that the most reasonable explanation for low N2 fixation rates and low growth rates of heterotrophic prokaryotes in the open ocean is a lack of sufficient energy in the form of bioavailable carbon. In experiments conducted parallel to this study, abundances of γ-24774A11 increased over a 3-day incubation period relative to a control treatment, in response to sugar additions (Moisander et al., 2011). This suggests that availability of energy may be a key factor regulating the growth of γ-24774A11 and perhaps other heterotrophic diazotrophs. The positive correlation with DOC in this study supports this hypothesis.

Although the availability of DOC may be a growth limiting factor, suggesting a positive link with phytoplankton production, oligotrophy was thought to promote the abundance of the γ-24774A11-related phylotype in the Arabian Sea (Bird et al., 2005). Similarly, in this study, γ-24774A11 had a negative correlation with chlorophyll. The presence of ammonium inhibits the enzyme synthesis in some diazotrophs (Postgate, 1990); however, N2 fixation in some open ocean diazotrophs appears to tolerate elevated ammonium (Dekaezemacker and Bonnet, 2011; Masuda et al., 2013). Nutrients increasing with depth with chlorophyll, especially DIN, may negatively influence fitness of γ-24774A11. NO3−, NO2−, TN and SRP all had a negative correlation with the abundance of γ-24774A11.

Major oceanic pelagic bacterial groups and ecotypes, including gammaproteobacteria, have depth stratification that may vary depending on season, and light adaptation and nutrient acquisition mechanisms (Johnson et al., 2006; Treusch et al., 2009). Similarly to this study, a study in the Southern California Bight (Hamersley et al., 2011) suggested primarily a surface association for γ-24774A11, while the phylotype was detected down to 300 m in the Arabian Sea (Bird et al., 2005). Surface-associated groups such as γ-24774A11 could supplement their energy from light directly through rhodopsin or bacteriochlorophyll-based metabolisms. Alternatively, the surface association could be an indication of an oligotrophic lifestyle or an advantage gained from phytoplankton photosynthesis products. Until isolates or genomic information of γ-24774A11 becomes available, its energy metabolism and nutritional requirements will remain unknown.

Abundances of γ-24774A11 correlated positively with other diazotrophs, particularly with C. watsonii. The γ-24774A11 phylotype had a significant positive relationship with temperature, shown also for C. watsonii in the area (Moisander et al., 2010). The overall conditions that promote growth of Trichodesmium and C. watsonii also seem to promote growth of γ-24774A11 (Supplementary Table S3). The γ-24774A11 distributions had a weaker relationship with UCYN-A, and were more constant than distributions of UCYN-A and Crocosphaera.

Transcript abundance

Nitrogenase gene transcription is strongly regulated in response to the presence of O2 and combined N (Dixon and Kahn, 2004; Martinez-Argudo et al., 2005). The consistent presence of nifH transcripts from γ-24774A11 over large geographic distances suggests that this phylotype contributes to N2 fixation over wide spatial and temporal scales. Consistent nifH expression during the day suggests it may occupy suboxic or anoxic microniches in live cells or dead particulate matter, and possibly uses active respiratory protection or other physiological mechanisms against O2 inhibition as found in its relative, A. vinelandii (Oelze, 2000).

Transcription by the γ-24774A11 phylotype has been reported previously during the day and night (Falcon et al., 2004; Church et al., 2005). The nifH gene expression by γ-24774A11 had a subtle diel pattern, with higher rates of expression at night, while such pattern was not obvious in a previous study conducted over 2 days (Church et al., 2005). The results suggest γ-24774A11 N2 fixation is controlled by different factors from UCYN-A, due to different ecological strategies in these organisms. Greater transcription at night could mean that reduced localized O2 tension at night is beneficial for this organism. Although generally not thought to have a major role in heterotrophic bacteria, circadian rhythms may be involved with non-photosynthetic bacteria such as Pseudomonas putida (Soriano et al., 2010). Diel rhythms in gene expression found in open ocean bacteria may thus reflect an inherent diel or circadian pattern even in heterotrophic microorganisms, or be a secondary result from changing environmental conditions due to cyclic pattern in availability of photosynthesis products (or O2) in the euphotic layers. It has been suggested that marine microbial gene expression may be synchronous across distant phylogenetic and functional groups reflecting changing environmental conditions (Ottesen et al., 2013). It should be noted that because some samples were kept in the deck incubator up to 12 h until the opposite light phase, it is possible that bottle effects influenced transcription.

Metatranscriptomic studies frequently use transcript abundances to estimate differential expression of metabolic pathways in the environment. Transcript abundances in this study can be used as a relative indicator of contributions of each of the diazotroph phylotypes to total nifH transcription activity. Our data suggest that γ-24774A11 may contribute up to 26% of the nifH gene transcription at a given time. The transcript abundances suggest N2 fixation rates in γ-24774A11 could be greater during the night than during the day, but the contribution to the total nifH gene transcript pool may be significant any time of the day. Although N2 fixation rates associated with γ-24774A11 remain to be demonstrated, transcript data suggest that when integrated over long distances and over the diurnal cycle, the phylotype may have a role in marine N2 fixation. Heterotrophic diazotrophs have been reported to be abundant and diverse in the marine environment. This study shows that at least one of these is widely distributed and has consistent nifH expression, and that its transcripts can be as or more abundant than in cyanobacteria. However, since it is difficult yet to measure N2 fixation of individual groups, the significance of heterotrophic N2 fixation remains an enigma.

References

Benavides M, Agawin NSR, Aristegui J, Ferriol P, Stal LJ . (2011). Nitrogen fixation by Trichodesmium and small diazotrophs in the subtropical northeast Atlantic. Aquat Microb Ecol 65: 43–53.

Bird C, Martinez JM, O'Donnell AG, Wyman M . (2005). Spatial distribution and transcriptional activity of an uncultured clade of planktonic diazotrophic gamma-proteobacteria in the Arabian Sea. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 2079–2085.

Bombar D, Moisander PH, Dippner JW, Foster RA, Voss M, Karfield B et al. (2011). Distribution of diazotrophic microorganisms and nifH gene expression in the Mekong River plume during intermonsoon. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 424: 39–52.

Bonnet S, Biegala IC, Dutrieux P, Slemons LO, Capone DG . (2009). Nitrogen fixation in the western equatorial pacific: rates, diazotrophic cyanobacterial size class distribution, and biogeochemical significance. Global Biogeochem Cycl 23: GB3012.

Bostrom KH, Riemann L, Kuhl M, Hagstrom A . (2007). Isolation and gene quantification of heterotrophic N-2-fixing bacterioplankton in the Baltic Sea. Environ Microbiol 9: 152–164.

Capone DG, Zehr JP, Paerl HW, Bergman B, Carpenter EJ . (1997). Trichodesmium, a globally significant marine cyanobacterium. Science 276: 1221–1229.

Carlson CA, Giovannoni SJ, Hansell DA, Goldberg SJ, Vergin K . (2004). Interactions among dissolved organic carbon, microbial processes, and community structure in the mesopelagic zone of the northwestern Sargasso Sea. Limnol Oceanogr 49: 1073–1083.

Carpenter EJ, Montoya JP, Burns J, Mulholland MR, Subramaniam A, Capone DG . (1999). Extensive bloom of a N-2-fixing diatom/cyanobacterial association in the tropical Atlantic Ocean. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 185: 273–283.

Chen Y, Zehr JP, Mellon MT . (1996). Growth and nitrogen fixation of the diazotrophic filamentous nonheterocystous cyanbacterium Trichodesmium sp. IMS 101 in defined media: evidence for a circadian rhythm. J Phycol 32: 916–923.

Church MJ, Short CM, Jenkins BD, Karl DM, Zehr JP . (2005). Temporal patterns of nitrogenase gene (nifH) expression in the oligotrophic North Pacific Ocean. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 5362–5370.

Dekaezemacker J, Bonnet S . (2011). Sensitivity of N-2 fixation to combined nitrogen forms (NO3- and NH4+) in two strains of the marine diazotroph Crocosphaera watsonii (Cyanobacteria). Mar Ecol Prog Ser 438: 33–46.

Diez B, Bergman B, Pedros-Alio C, Anto M, Snoeijs P . (2012). High cyanobacterial nifH gene diversity in Arctic seawater and sea ice brine. Environ Microbiol Rep 4: 360–366.

Dixon R, Kahn D . (2004). Genetic regulation of biological nitrogen fixation. Nat Rev Microbiol 2: 621–631.

Falcon LI, Carpenter EJ, Cipriano F, Bergman B, Capone DG . (2004). N-2 fixation by unicellular bacterioplankton from the Atlantic and Pacific oceans: phylogeny and in situ rates. Appl Environ Microbiol 70: 765–770.

Fay P . (1992). Oxygen relations of nitrogen fixatioin in cyanobacteria. Microbiol Rev 56: 340–373.

Fong AA, Karl DM, Lukas R, Letelier RM, Zehr JP, Church MJ . (2008). Nitrogen fixation in an anticyclonic eddy in the oligotrophic North Pacific Ocean. ISME J 2: 663–676.

Foster RA, Paytan A, Zehr JP . (2009). Seasonality of N-2 fixation and nifH gene diversity in the Gulf of Aqaba (Red Sea). Limnol Oceanogr 54: 219–233.

Graziano LM, Geider RJ, Li WKW, Olaizola M . (1996). Nitrogen limitation of North Atlantic phytoplankton: analysis of physiological condition in nutrient enrichment experiments. Aquat Micr Ecol 11: 53–64.

Halm H, Lam P, Ferdelman TG, Lavik G, Dittmar T, LaRoche J et al. (2012). Heterotrophic organisms dominate nitrogen fixation in the South Pacific Gyre. The ISME J 6: 1238–1249.

Hamersley MR, Turk KA, Leinweber A, Gruber N, Zehr JP, Gunderson T et al. (2011). Nitrogen fixation within the water column associated with two hypoxic basins in the Southern California Bight. Aquat Micr Ecol 63: 193–205.

Hewson I, Moisander PH, Achilles KM, Carlson CA, Jenkins BD, Mondragon EA et al. (2007). Characteristics of diazotrophs in surface to abyssopelagic waters of the Sargasso Sea. Aquat Micr Ecol 46: 15–30.

Johnson ZI, Zinser ER, Coe A, McNulty NP, Woodward M, Chisholm SW . (2006). Niche partitioning among Prochlorococcus ecotype abundances in the North Atlantic Ocean revealed by an improved quantitative PCR method. Science 311: 1737–1740.

Karl D, Letelier R, Tupas L, Dore J, Christian J, Hebel D . (1997). The role of nitrogen fixation in biogeochemical cycling in the subtropical North Pacific Ocean. Nature 388: 533–538.

Karl DM, Tien G . (1992). MAGIC: A sensitive and precise method for measuring dissolved phosphorus in aquatic environments. Limnol Oceanogr 37: 105–116.

Kirchman DL, Meon B, Cottrell MT, Hutchins DA, Weeks D, Bruland KW . (2000). Carbon versus iron limitation of bacterial growth in the California upwelling regime. Limnol Oceanogr 45: 1681–1688.

Langlois RJ, LaRoche J, Raab PA . (2005). Diazotrophic diversity and distribution in the tropical and subtropical Atlantic ocean. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 7910–7919.

Le Moal M, Biegala IC . (2009). Diazotrophic unicellular cyanobacteria in the northwestern Mediterranean Sea: a seasonal cycle. Limnol Oceanogr 54: 845–855.

Ludwig W, Strunk O, Westram R, Richter L, Meier H, Yadhukumar et al. (2004). ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 1363–1371.

Mahaffey C, Michaels AF, Capone DG . (2005). The conundrum of marine N-2 fixation. Am J Sci 305: 546–595.

Man-Aharonovich D, Kress N, Bar Zeev E, Berman-Frank I, Beja O . (2007). Molecular ecology of nifH genes and transcripts in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Environ Microbiol 9: 2354–2363.

Martinez-Argudo I, Little R, Shearer N, Johnson P, Dixon R . (2005). Nitrogen fixation: key genetic regulatory mechanisms. Biochem Soc Trans 33 (part 1): 152–156.

Masuda T, Furuya K, Kodama T, Takeda S, Harrison PJ . (2013). Ammonium uptake and dinitrogen fixation by the unicellular nanocyanobacterium Crocosphaera watsonii in nitrogen-limited continuous cultures. Limnol Oceanogr 58: 2029–2036.

Mills MM, Ridame C, Davey M, La Roche J, Geider RJ . (2004). Iron and phosphorus co-limit nitrogen fixation in the eastern tropical North Atlantic. Nature 429: 292–294.

Moisander PH, Beinart RA, Hewson I, White AE, Johnson KS, Carlson CA et al. (2010). Unicellular cyanobacterial distributions broaden the oceanic N-2 fixation domain. Science 327: 1512–1514.

Moisander PH, Beinart RA, Voss M, Zehr JP . (2008). Diversity and abundance of diazotrophic microorganisms in the South China Sea during intermonsoon. ISME J 2: 954–967.

Moisander PH, Zhang R, Boyle EA, Hewson I, Montoya JP, Zehr JP . (2011). Analogous nutrient limitations in unicellular diazotrophs and Prochlorococcus in the South Pacific Ocean. ISME J 6: 733–744.

Montoya JP, Holl CM, Zehr JP, Hansen A, Villareal TA, Capone DG . (2004). High rates of N-2 fixation by unicellular diazotrophs in the oligotrophic Pacific Ocean. Nature 430: 1027–1031.

Oelze J . (2000). Respiratory protection of nitrogenase in Azotobacter species: is a widely held hypothesis unequivocally supported by experimental evidence? FEMS Microbiol Rev 24: 321–333.

Omoregie EO, Crumbliss LL, Bebout BM, Zehr JP . (2004). Determination of nitrogen-fixing phylotypes in Lyngbya sp and Microcoleus chthonoplastes cyanobacterial mats from Guerrero Negro, Baja California, Mexico. Appl Environ Microbiol 70: 2119–2128.

Ottesen EA, Young CR, Eppley JM, Ryan JP, Chavez FP, Scholin CA et al. (2013). Pattern and synchrony of gene expression among sympatric marine microbial populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: E488–E497.

Postgate J (ed).. (1990) Nitrogen fixation Second edition Edward Arnold: Great Britain.

Rabouille S, Staal M, Stal LJ, Soetaert K . (2006). Modeling the dynamic regulation of nitrogen fixation in the cyanobacterium Trichodesmium sp. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 3217–3227.

Rediers H, Vanderleyden J, De Mot R . (2004). Azotobacter vinelandii: a Pseudomonas in disguise? Microbiology 150: 1117–1119.

Sakamoto CM, Friederich GE, Codispoti LA . (1990) MBARI Procedures for Automated Nutrient Analyses Using a Modified Alpkem Series 300 Rapid Flow Analyzer. Monteray Bay Aquarium Research Institute.

Shi T, Ilikchyan I, Rabouille S, Zehr JP . (2010). Genome-wide analysis of diel gene expression in the unicellular N-2-fixing cyanobacterium Crocosphaera watsonii WH 8501. ISME J 4: 621–632.

Short SM, Zehr JP . (2005). Quantitative analysis of nifH genes and transcripts from aquatic environments. Meth Enzymol 397: 380–394.

Short SM, Zehr JP . (2007). Nitrogenase gene expression in the Chesapeake Bay Estuary. Environ Microbiol 9: 1591–1596.

Soriano M, Roibas B, Garcia AB, Espinosa-Urgel M . (2010). Evidence of circadian rhythms in non-photosynthetic bacteria? J Circadian Rhythms 8: 8.

Staal M, Hekkert StL, Brummer GJ, Veldhuis M, Sikkens C, Persijn S et al. (2007a). Nitrogen fixation along a north-south transect in the eastern Atlantic Ocean. Limnol Oceanogr 52: 1305–1316.

Staal M, Rabouille S, Stal LJ . (2007b). On the role of oxygen for nitrogen fixation in the marine cyanobacterium Trichodesmium sp. Environ Microbiol 9: 727–736.

Strickland JDH, Parsons TR . (1972) A Practical Handbook Of Seawater Analysis. Bulletin 167 2nd edn Fisheries Reserach Board Ottawa: Canada.

Thingstad TF, Bellerby RGJ, Bratbak G, Borsheim KY, Egge JK, Heldal M et al. (2008). Counterintuitive carbon-to-nutrient coupling in an Arctic pelagic ecosystem. Nature 455: 387–U337.

Thompson AW, Foster RA, Krupke A, Carter BJ, Musat NM, Vaulot D et al. (2012). Unicellular cyanobacterium symbiotic with a single-celled eukaryotic alga. Science 337: 1546–1550.

Treusch AH, Vergin KL, Finlay LA, Donatz MG, Burton RM, Carlson CA et al. (2009). Seasonality and vertical structure of microbial communities in an ocean gyre. ISME J 3: 1148–1163.

Tripp HJ, Bench SR, Turk KA, Foster RA, Desany BA, Niazi F et al. (2010). Metabolic streamlining in an open-ocean nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium. Nature 464: 90–94.

Tuit C, Waterbury J, Ravizzaz G . (2004). Diel variation of molybdenum and iron in marine diazotrophic cyanobacteria. Limnol Oceanogr 49: 978–990.

Turk KA, Rees AP, Zehr JP, Pereira N, Swift P, Shelley R et al. (2011). Nitrogen fixation and nitrogenase (nifH) expression in tropical waters of the eastern North Atlantic. ISME J 5: 1201–1212.

Villareal TA . (1994). Widespread occurrence of the Hemiaulus-cyanobacterial symbiosis in the southwest North Atlantic ocean. Bull Mar Sci 54: 1–7.

Walsh TW . (1989). Total dissolved nitrogen in seawater: A new high combustion method and a comparison to photo-oxidation. Mar Chem 26: 295–311.

Welschmeyer NA . (1994). Fluorometric analysis of chlorophyll a in the presence of chlorophyll b and pheopigments. Limnol Oceanogr 39: 1985–1992.

Zehr JP, Bench SR, Carter BJ, Hewson I, Niazi F, Shi T et al. (2008). Globally distributed uncultivated oceanic N-2-Fixing Cyanobacteria lack Oxygenic Photosystem II. Science 322: 1110–1112.

Zehr JP, Crumbliss LL, Church MJ, Omoregie EO, Jenkins BD . (2003a). Nitrogenase genes in PCR and RT-PCR reagents: implications for studies of diversity of functional genes. Biotechniques 35: 996–1002.

Zehr JP, Jenkins BD, Short SM, Steward GF . (2003b). Nitrogenase gene diversity and microbial community structure: a cross-system comparison. Environ Microbiol 5: 539–554.

Zehr JP, Kudela RM . (2011). Nitrogen Cycle of the Open Ocean: From Genes to Ecosystems 197–225 in Carlson CA, Giovannoni SJ (eds). Annual Review of Marine Science Vol 3 Annual Reviews: Palo Alto, CA, USA.

Zehr JP, Mellon MT, Zani S . (1998). New nitrogen-fixing microorganisms detected in oligotrophic oceans by amplification of nitrogenase (nifH) genes. Appl Environ Microbiol 64: 3444–3450.

Zehr JP, Paerl HW . (1998). Nitrogen fixation in the marine environment: genetic potential and nitrogenase expression. in Cooksey KE (ed). Molecular approaches to the study of the ocean. Chapman & Hall: London, pp 285–301.

Zehr JP, Turner PJ . (2001). Nitrogen fixation: nitrogenase genes and gene expression. Methods in Microbiol 30: 271–286.

Zehr JP, Waterbury JB, Turner PJ, Montoya JP, Omoregie E, Steward GF et al. (2001). Unicellular Cyanobacteria fix N-2 in the subtropical North Pacific Ocean. Nature 412: 635–638.

Zhang J-Z . (2000). Shipboard automatic determination of trace concentrations of nitrite and nitrate in oligotrophic water by gas-segmented continuous flow analysis with a liquid waveguide capillary flow cell. Deep Sea Res I- Oceanogr Res Paper 47: 1157–1171.

Acknowledgements

We thank I Hewson, I Biegala, M Furnas, E Preston, K Sandman and personnel onboard R/V Kilo Moana for technical assistance, and J Montoya, C Carlson, K Johnson, A White for hydrographic, nutrient and DOC analyses. This study was supported by a first phase Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation Marine Investigator ship award (JPZ), NSF C-MORE (EF0424599) (JPZ), NSF OCE1130495 (PHM) and funds from the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth (PHM).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moisander, P., Serros, T., Paerl, R. et al. Gammaproteobacterial diazotrophs and nifH gene expression in surface waters of the South Pacific Ocean. ISME J 8, 1962–1973 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.49

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.49

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Quantification of aquatic unicellular diazotrophs by immunolabeled flow cytometry

Biogeochemistry (2023)

-

Cell-specific measurements show nitrogen fixation by particle-attached putative non-cyanobacterial diazotrophs in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Phylogenetically and catabolically diverse diazotrophs reside in deep-sea cold seep sediments

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Transcriptional responses of Trichodesmium to natural inverse gradients of Fe and P availability

The ISME Journal (2022)

-

Evidence of the Significant Contribution of Heterotrophic Diazotrophs to Nitrogen Fixation in the Eastern Indian Ocean During Pre-Southwest Monsoon Period

Ecosystems (2022)