Abstract

The Arctic Ocean plays a critical role in controlling nutrient budgets between the Pacific and Atlantic Ocean. Archaea are key players in the nitrogen cycle and in cycling nutrients, but their community composition has been little studied in the Arctic Ocean. Here, we characterize archaeal assemblages from surface and deep Arctic water masses using massively parallel tag sequencing of the V6 region of the 16S rRNA gene. This approach gave a very high coverage of the natural communities, allowing a precise description of archaeal assemblages. This first taxonomic description of archaeal communities by tag sequencing reported so far shows that it is possible to assign an identity below phylum level to most (95%) of the archaeal V6 tags, and shows that tag sequencing is a powerful tool for resolving the diversity and distribution of specific microbes in the environment. Marine group I Crenarchaeota was overall the most abundant group in the Arctic Ocean and comprised between 27% and 63% of all tags. Group III Euryarchaeota were more abundant in deep-water masses and represented the largest archaeal group in the deep Atlantic layer of the central Arctic Ocean. Coastal surface waters, in turn, harbored more group II Euryarchaeota. Moreover, group II sequences that dominated surface waters were different from the group II sequences detected in deep waters, suggesting functional differences in closely related groups. Our results unveiled for the first time an archaeal community dominated by group III Euryarchaeota and show biogeographical traits for marine Arctic Archaea.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Arctic Ocean plays a crucial role in controlling the productivity of the world oceans through regulating nutrient budgets and cycling nitrogen between regions of high denitrification activity and net nitrogen fixation. Water flowing into the Arctic from the Pacific Ocean through the Bering Strait is depleted in nitrate with respect to phosphate (Jones et al., 2003). This water flows out through the Canadian archipelago and Fram Strait to the Atlantic Ocean where microorganisms use phosphate to fix nitrogen. Through its Arctic journey the water's nutrient properties change (Yamamoto-Kawai et al., 2006), and this change probably influences primary production at a global scale. Although marine microorganisms are a major component of nutrient cycles (Arrigo 2005), the diversity and distribution of microbial communities in general remain poorly understood, and because of logistic constraints the Arctic is especially underexplored.

Archaea were first described as extremophiles, but are now recognized as ubiquitous and abundant in both marine (Karner et al., 2001) and freshwaters environments (Auguet and Casamayor 2008). Marine Archaea are phylogenetically distributed through four main taxonomical clusters: one cluster of Crenarchaeota, the Marine group I (MGI), and three clusters of Euryarchaeota, group II, III and IV. The only cultivated representative of planktonic Archaea is known to oxidize ammonia and belongs to Crenarchaeota MGI (Konneke et al., 2005). Recent evidence indicates that MGI Crenarchaeota are key players in chemoautotrophic ammonia oxidation (Hallam et al., 2006b; Francis et al., 2007), although other new data suggest that there are vertical and latitudinal gradients in the abundance of putative Crenarchaeota nitrifiers in the Atlantic Ocean and that some Crenarchaeota may live heterotrophically (Agogue et al., 2008). The abundance of Crenarchaeota and their key role on the global nitrogen cycle makes them a fundamental component of the marine ecosystem. There are no cultivated representatives of marine planktonic Euryarchaeota to date and the functional role of that archaeal phylum remains little understood.

The MGI Crenarchaeota and group II Euryarchaeota are the most abundant Archaea in the oceans (Massana et al., 2000). In temperate and tropical oceans Crenarchaeota are believed to be more frequent in deep waters, whereas group II Euryarchaeota are often more abundant in surface waters (Karner et al., 2001; Herndl et al., 2005; DeLong et al., 2006). In the Arctic, the distribution of the different archaeal groups remains poorly resolved. One study found low abundance of group II Euryarchaeota down to 500 m (Kirchman et al., 2007), other studies showed communities dominated by group II Euryarchaeota in surface waters (Galand et al., 2006, 2008b), whereas a basin-wide survey described Crenarchaeota as more abundant than Euryarchaeota at 55 and 131 m (Bano et al., 2004). The differing conclusions of these studies may be because of the use of different methods (Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) versus clone libraries), but could also be linked to the physical oceanography of the Arctic region, where archaeal groups are more closely linked to parent water masses than to depth alone (Galand et al., 2009). The diversity and distribution of archaeal communities in the deeper Arctic Ocean remains unexplored.

The aim of this study was to describe the composition of archaeal assemblages in the Arctic Ocean, and to resolve the distribution of archaeal diversity within different water masses. We targeted five different water masses from both the coastal and central Arctic Ocean, that is, the coastal Pacific surface water and the polar mixed layer in the Beaufort Sea, the lower halocline and deep Atlantic water from the Canada Basin, and intermediate water from the Baffin Bay. To get an extended description of the diversity and a high coverage of the in situ populations, we characterized the archaeal assemblages by applying massively parallel tag sequencing to the hypervariable V6 region of the 16S rRNA gene (Sogin et al., 2006). We assigned a taxonomical identity to the archaeal sequence tags and were able to describe unique assemblages within the archaeal community.

Materials and methods

Sampling sites and collection

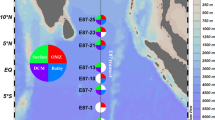

We used eight samples collected from different geographical regions of the western Arctic Ocean (Figure 1). Sample DAO_0002, 0006 and 0008 were collected from the Canadian icebreaker CCGS Louis St Laurent as part of the International Polar Year study Canada's three Oceans project (C3O), ACB_0014 was collected from the CCGS Amundsen as part of the Canadian Arctic Shelf Exchange Study. Samples ACB_0009, 0010, 0011 and 0012 were collected as described earlier (Kirchman et al., 2007; Malmstrom et al., 2007). All ACB samples were collected from surface water masses, whereas the DAO samples were from deeper water masses. The water mass definition followed earlier descriptions (McLaughlin et al., 2004; Rudels et al., 2004; Tang et al., 2004). DAO_0002 was from the Baffin Bay intermediate water, DAO_0006 from the deep Atlantic water and DAO_0008 from the lower halocline of the Canada Basin (Table 1). Samples ACB_0009, 0010, 0011 and 0012 were from the Pacific surface water taken from the Chukchi and Beaufort Sea (Table 1). Sample ACB_0014 was from the polar mixed layer taken in Franklin Bay in the Amundsen Gulf.

The DAO and ACB_0014 samples were collected with a rosette system equipped with a Seabird (Bellevue, WA, USA) 911 conductivity temperature and depth profiler. The rosette system was fitted with 12-L PVC bottles (Ocean Test Equipment Inc., Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA). Bottles were tripped on the upcast and seawater was collected from the rosette into bottles that had been cleaned in 10% (v/v) HCL, rinsed thrice with MilliQ water, and then thrice with sample water before filling. Within 30 min of collection, 6 l of seawater were filtered successively through a 50-μm mesh, 3-μm pore size 47-mm polycarbonate filter, and finally through a 0.2-μm pore size Sterivex unit (Millipore Canada Ltd, Mississauga, ON, USA). The whole cell concentrates in the Sterivex unit were preserved in 1.8 ml of buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.75 M sucrose and 40 mM EDTA) and frozen at −80°C. Other ACB samples were collected as described earlier (Malmstrom et al., 2007).

Chlorophyll a was estimated using standard techniques (Nusch 1980). Total prokaryote counts for the DAO samples were kindly supplied by Dr WKW Li (Bedford Institute of Oceanography, Halifax, NS, Canada) from flow cytometry counts, and from microscopic analysis for ACB samples.

DNA extraction and pyrosequencing

DNA was extracted by digesting the cells with lysozyme (final concentration, 1 mg ml−1) and proteinase K (0.21 mg ml−1). Nucleic acids were then separated with phenol/chloroform (ACB samples) or a salt solution (DAO samples), and precipitated with ethanol. Earlier experiences indicated no differences in DNA recovery efficiency between the two techniques (C Lovejoy unpublished data). The archaeal hypervariable V6 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using primers: 958arcF 5′-AATTGGANTCAACGCCGG-3′, 1048arcRmajor 5′-CGRCGGCCATGCACCWC-3′ and 1048arcR-minor 5′-CGRCRGCCATGYACCWC-3′ under conditions described in Huber et al. (2007). The final 90-bp amplicon was sequenced with 454 Life Sciences GS20 sequencer at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, MA, USA. For each read from the sequencer the primer bases were trimmed from the beginning and the end, and low-quality sequences were removed Huse et al. (2007). Sequences were flagged as low quality when they were <50 nucleotides in length, the start of the sequence did not exactly match a primer sequence, sequences contained ambivalent nucleotide assignments with one or more Ns (unknown nucleotides) or if the first five nucleotides of a tag did not correspond to the expected five nucleotides run key (used to sort the pyrosequencing reads). All sequences obtained for this study will be made publicly available at http://vamps.mbl.edu/.

Identification of archaeal phylotypes

The taxonomical identification of the sequence reads (tags) followed the approach proposed by Sogin et al. (2006). The tags were compared by BLASTN to a reference database of hypervariable region tags based on the SILVA database (version 94) (Pruesse et al., 2007), and the 100 best matches were aligned to the tag sequences using MUSCLE (Edgar 2004). A reference sequence or sequences were defined as those having the minimum global distance (number of insertions, deletions and mismatches divided by the length of the tag) to the tag sequence, and all reads showing the best match to the same reference V6 tag were grouped together as the same operational taxonomic unit (OTU) (Sogin et al., 2006). Taxonomy was assigned to each reference sequence with the RDP Classifier (Wang et al., 2007).

This automated pipeline was, however, not precise enough to classify Archaea below the phylum level. To enhance the precision of the taxonomical affiliation, a representative sequence from each OTU was sent to the SeqMatch tool of the RDP Release 10 (Cole et al., 2009), and up to three sequences rendering the best seqmatch score to the pyrosequencing reads were used as additional reference sequences. Reference sequences were aligned using the CLUSTAL W package (Thompson et al., 1994) and trimmed down to an overlapping region present in all sequences; the final length of the overlapping region was 600 bp. A Jukes–Cantor corrected distance matrix was generated from the reference sequences with DNADIST and a tree was constructed using the FITCH program from PHYLIP (Felsenstein 2004). The different clusters composing the distance tree were then identified.

Diversity estimations and cluster analysis

Tags were aligned and a Jukes–Cantor corrected distance matrix was obtained using the DNADIST program from PHYLIP (Felsenstein 2004). Rarefaction, the ACE and the Chao1 nonparametric richness estimators were then calculated with the program DOTUR (Schloss and Handelsman 2005). The 3% distance level between tag sequences was used for calculation of diversity estimators.

For cluster analysis, a distance matrix was computed from the abundance of OTU present in each community using Bray–Curtis similarity and a dendrogram was inferred with the unweighted pair-group average algorithm (UPGMA) as implemented in the program PAST (v 1.8, http://folk.uio.no/ohammer/past/).

Results

Characteristic of the water masses

Sample DAO_0002 was from the Baffin Bay intermediate water (Table 1), most often defined as having a temperature (T)>0 °C and a salinity (S)>34 (Tang et al., 2004). Baffin Bay intermediate water originates from the mixing of the North Atlantic water flowing northward with the West Greenland current, and the Arctic water flowing southward through Smith Sound (Rudels et al., 2004; Tang et al., 2004). Samples DAO_0006 was from the deep Atlantic water and DAO_0008 from the lower halocline in the Canada Basin (Table 1). The Arctic Atlantic layer derives from the Norwegian Sea and ultimately from the North Atlantic. The Atlantic layer has T⩾0 °C and S⩾34.5 and is situated below the halocline. The halocline is defined as a pycnocline with higher temperature situated between the polar mixed layer (surface layer) and the Atlantic layer (Rudels et al., 2004). Samples ACB_0009, 0010, 0011 and 0012 were from coastal water sampled in the Beaufort Sea off Point Barrow (Alaska) and represent the Pacific surface water (Table 1). The Pacific water enters the Arctic through the Bering Strait, and the water salinity and temperature is altered through freshwater runoffs and ice melting and formation (McLaughlin et al., 2004). Sample ACB_0014 was from the polar mixed layer taken in Franklin Bay, Amundsen Gulf (Table 1). The polar mixed layer is a low salinity layer influenced by water of the Pacific origin and freshwater from the Mackenzie River (Garneau et al., 2008).

Diversity of the archaeal assemblages

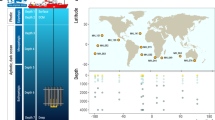

After removing low quality tags, the sequencing effort yielded a total of 195 107 reads for the eight samples analyzed, with on average 24 388 tags per sample (Table 1). The tags had a mean length of 69 nucleotides after trimming the primers. The coverage of the libraries was high with rarefaction curves reaching an asymptote at the 3% difference level (Figure 2). For six of the eight communities analyzed, the number of OTU detected was close to the total number of OTU estimated by Chao1 and ACE diversity indices, additional evidence that the natural communities were well covered by the sequencing effort (Table 1). Surface samples and deep-water samples were distinct from each other and shared only 28% of OTUs in common. Overall, evenness was low and a small number of sequences were highly represented in the samples. In the surface samples, just three sequences accounted for >80% of all sequences recovered in the dataset. In the deep samples, six sequences accounted for >80% of all sequences.

Samples from coastal surface waters had generally higher diversity than samples from deeper water masses, and the polar mixed layer from the surface of Franklin Bay had overall the highest estimated richness (Figure 1, Table 1). The Baffin Bay intermediate water sample had the lowest richness, as its diversity was nearly half of that estimated for surface Beaufort Sea waters (Table 1).

Composition and distribution of archaeal assemblages

Clustering analysis of the archaeal community composition separated the samples in two main clusters: one contained all samples from deep-water masses and the other, all surface samples (Figure 3). Within surface water communities, sample ACB_0011 formed a separate branch indicative of a distinct archaeal assemblage. Sample ACB_0014 from the polar mixed layer in Franklin Bay was close to the other samples from the Pacific surface waters (Figure 3). Among deep-water samples, the two samples from the deep Atlantic water and lower halocline in the Canada Basin grouped together separately from Baffin Bay intermediate water communities (Figure 3).

Dendrogram representing the similarity between tag composition of eight archaeal assemblages from surface (ACB) and deep (DAO) water masses of the Arctic Ocean described in Table 1. Clustering is on the basis of a distance matrix computed with Bray–Curtis index of similarity. The dendrogram was inferred with the unweighted pair-group average algorithm (UPGMA).

MGI Crenarchaeota was overall the most abundant group in the Arctic Ocean and comprised between 27% and 63% of all tags. The deep Baffin Bay sample had the highest proportion of MGI Crenarchaeota, whereas the deep central Arctic had the lowest (Figure 4). The most abundant MGI sequences, representing >40% of the identified tags, belonged to the same cluster (MGI cluster A, Supplementary Figure S1). Within that cluster, the most abundant tag was not only 100% similar to the 16S rRNA sequence of Nitrosopumilus maritimus, but also to environmental sequences retrieved from various ecosystems, ranging from marine sediments and deep oceanic water masses to a freshwater rhizophere. Sequences had best BLAST matches among others to OTUA, OTUB and OTUC clusters defined earlier by Martin-Cuadrado et al. (2008). Within MGI cluster A, a relatively abundant (up to 5% of the tags) sub-cluster (KM3–69, Supplementary Figure S1) was found specifically in the deep Arctic and was almost absent from surface waters (<0.2% of the tags). That cluster had 96% similarity to the target V6 region of 16S rRNA of N. maritimus. A second, less abundant cluster of MGI (MGI cluster B, Supplementary Figure S1) was detected mainly in the Pacific surface waters. Cluster MGI cluster B contained mainly sequences from sea sediments and was closely related to N. maritimus (98% sequence similarity). A few representative sequences of the newly defined Crenarchaeota group 1A (DeLong et al., 2006) were also detected in deep Arctic samples, but at very low abundance (<200 tags). Only one group 1A tag was detected from surface samples.

Composition of eight archaeal assemblages from the Arctic Ocean. Naming of the different archaeal groups follows the clusters defined in Supplementary Figure S1.

Group III Euryarchaeota was the most abundant archaeal group in sample DAO_0006 from the deep Atlantic water, and represented the second most abundant tags, after group I Crenarchaeota, in the lower halocline (DAO_0008) and Baffin Bay intermediate waters (DAO_0002) (Figure 4). Group III Euryarchaeotal sequences grouped into two clusters. The most abundant sequences grouped into the OTU D cluster (Supplementary Figure S1), following the designation by Martin-Cuadrado et al. (2008). V6 tags belonging to OTU D were not only 100% similar to sequences from the deep Southern Ocean, the Mediterranean and the Pacific Ocean (Mehta et al., 2005; Martin-Cuadrado et al., 2008), but also from shallower (200 m) waters of the Pacific (Mincer et al., 2007). A second less abundant V6 tag belonged to a cluster of group III Euryarchaeota, which we named cluster DH148-W24 after its first representative (López-García et al., 2001). The tag was 100% similar to sequences retrieved from deep-water masses of the North and South Atlantic and the Pacific Ocean (DeLong et al., 2006; López-García et al., 2001). Very few group III Euryarchaeota sequence tags were detected in surface waters (<0.4 % of all tags); they all belonged to OTU D cluster.

In Pacific surface waters, the second most abundant archaeal group was group II Euryarchaeota. Group II contained the most abundant group of sequences in samples ACB_0010, ACB_0011 and ACB_0014 (Figure 4). Group II Euryarchaeota sequences are grouped under three main clusters (Supplementary Figure S1). Most of the group II sequences from surface waters belonged to group II.a (Figure 4). The most abundant cluster II.a tags had the highest similarity (98%) to sequences from marine sediments (Clementino et al., 2007) and surface Pacific waters (Frigaard et al., 2006). In deep waters, the most abundant group II sequences belonged to cluster II.b (Figure 4). They had the highest similarity (100%) to sequences retrieved from deep waters of the Atlantic and the Pacific Ocean. Other deep-water group II sequences grouped within cluster II.c, earlier named OTU F (Martin-Cuadrado et al., 2008) containing sequences from deep-water masses (Supplementary Figure S1).

The sample from the Beaufort Sea (Sample ACB_0011) had a distinct community composition from all other samples. The community was composed almost entirely of group II Euryarchaeota (>99% of the sequences), whereas MGI Crenarchaeota were practically absent (0.40 % of the sequences). One single group II tag represented >85% of the sequences. It was 100% similar to a sequence retrieved from surface waters of the Californian coast (AF257278).

Group IV sequences were detected in six of the eight samples, but were 50–200 times more abundant in deep-water samples from the central Arctic than in surface waters (Figure 4). Group IV Euryarchaeota were 100% similar to DH148-Y16 from deep-water masses of the South Atlantic (López-García et al., 2001).

Discussion

The importance of microorganisms in regulating nutrient and biogeochemical cycles is well recognized (Arrigo 2005). The temporal dynamics and distribution of marine microbial diversity remains, however, far from being completely understood, as entire oceanic regions such as the deep Arctic Ocean have never been explored. Here, we applied massively parallel tag sequencing as a tool to enhance our understanding of the diversity and distribution of archaeal assemblages in the Arctic Ocean, a poorly studied though globally important oceanic province. We were able to associate tags of the 16S rRNA gene hypervariable V6 region to taxonomical clusters within the uncultured Archaea, at a resolution precise enough to detect patterns in population distribution. We could thus identify the composition of archaeal assemblages from different water masses and unveiled unique patterns of diversity in the Arctic Ocean.

A surprising finding was that group III Euryarchaeota dominated the deep Atlantic water masses from the central Arctic (>40% of tag sequences) and was the second most abundant group in the two other deep-water samples. This is the first time group III is reported as dominating an archaeal assemblage. Group III Euryarchaeota were first identified in the Northeast Pacific (Fuhrman and Davis 1997) and was later detected in different parts of the Mediterranean Sea (Massana et al., 2000; Martin-Cuadrado et al., 2007, 2008), the South Atlantic (Martin-Cuadrado et al., 2007; López-García et al., 2001) and in the North Pacific Ocean (DeLong et al., 2006). However, group III is usually rarely represented in marine ecosystems, in which MGI Crenarchaeota and group II Euryarchaeota are the most abundant groups (Massana et al., 2000). The depths from which group III has been retrieved suggest that it is specific to the deep ocean. In fact, group III was absent or rare in clone libraries and Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis analysis from the upper layers of the central Arctic (Bano et al., 2004) and coastal Beaufort Sea (Galand et al., 2006, 2008a). One recent report from 1000 m depth in the South Atlantic described an archaeal assemblage, in which group III was the second most abundant group of sequences retrieved (Martin-Cuadrado et al., 2008). Remarkably, the same authors did not detect group III in nearby waters from the Antarctic Polar Front, suggesting a water mass-related occurrence of the group. Thus, the high abundances of group III in the deep Arctic Ocean and in one sample of the South Atlantic could indicate that the group successfully thrives in deep high latitude water masses, and that it deserves specific attention in future polar studies using quantitative methods such as FISH or qPCR.

Unfortunately, there are no cultivated representatives of group III Euryarchaeota to date and the metabolism and ecological role of those organisms remain unknown. Recently, however, metagenomic analysis revealed the presence in group III DNA fragments of genes that resembled those found in ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, suggesting that at least some members of group III Archaea may oxidize ammonia (Martin-Cuadrado et al., 2008). If this is confirmed, the abundant presence of group III Euryarchaeota in the deep Arctic water could imply an important role for that group in the nitrogen cycle at high latitudes, and raises the question of possible competition with ammonia-oxidizing Crenarchaeota.

We found the highest proportion of group I Crenarchaeota (MGI) (65% of the sequences) in waters from the Baffin Bay intermediate layers. MGI Archaea were detected earlier in various oceanic regions and are believed to constitute the most abundant microbial group in deep waters (Karner et al., 2001; DeLong et al., 2006). In the Arctic, however, high proportions of MGI Crenarchaeota were found in Archaea clone libraries from surface layers of the Beaufort Sea (Galand et al., 2008a, 2008b), in the upper layers of the Central Arctic (Bano et al., 2004) and in the western part of the Arctic Ocean, where almost no Euryarchaeota were detected with FISH (Kirchman et al., 2007). Generally, Arctic MGI Crenarchaeota seemed to be more abundant in oligotrophic offshore waters (Galand et al., 2008b).

One single representative of MGI has been isolated so far, N. maritimus (Konneke et al., 2005), and the genome of the marine sponge symbiont Cenarchaeum symbiosum has been described (Hallam et al., 2006a). The ability of those strains to oxidize ammonia and the wide abundance of archaeal genes putatively encoding the ammonia monooxygenase subunit A (amoA) all point to an important role of Crenarchaeota in the global nitrogen cycle (Wuchter et al., 2006; Lam et al., 2007), but recent findings have balanced this view suggesting that not all MGI Crenarchaeota are ammonia oxidizers. Recent data showed strong vertical and latitudinal gradients in the ratio of archaeal amoA to crenarchaeal 16S rRNA genes in the Atlantic Ocean (Agogue et al., 2008). Similarly a low amoA to 16S rRNA ratio was reported from an Arctic meromictic lake (Pouliot et al., 2009) and other data suggest that some Crenarchaeota are heterotrophic (Teira et al., 2006; Kirchman et al., 2007). However, the archaeal amoA gene is abundant in the Arctic, indicating that Crenarchaeota contribute to nitrogen cycling in the Arctic Ocean (Galand et al., 2009). In fact, the most common MGI tag (MGI cluster A), detected in both surface and deep-water mass samples had 100% similarity to the 16S rRNA gene of N. maritimus, suggesting that the detected Crenarchaeota were indeed ammonia oxidizers. On the other hand, we noted that the same tag also had a 100% match to sequences belonging to three other MGI clusters (OTU A, B and C in (Martin-Cuadrado et al., 2008). As the tag was identical to sequences belonging to different crenarchaeotal groups, its affiliation could not be precisely resolved. This result clearly shows that the V6 region is relatively conserved among several MGI clusters. Longer reads, including additional hypervariable 16S rRNA gene regions, may be needed to increase taxonomical resolution. The tag approach, however, successfully separated other MGI clusters. Cluster KM3–69, for instance, was specifically detected in deep-water layers, whereas cluster MGI cluster B was specifically found in surface waters. MGI cluster B tags were similar to sequences retrieved from sediments, which may indicate that the presence of the group in coastal waters may be influenced by sediment re-suspension or discharge from riverine runoffs.

Group II Euryarchaeota was the second most abundant group after Crenarchaeota in the surface layers. Group II is generally thought to be more abundant in surface waters (Karner et al., 2001; Herndl et al., 2005; DeLong et al., 2006), but in the Arctic, contrasting distributions have been reported. Group II Euryarchaeota were almost absent in FISH samples from the Western Arctic (Kirchman et al., 2007), which is heavily influenced by Pacific waters, but this group was abundant in central Arctic clone libraries (Bano et al., 2004) and dominated clone sequences from surface waters on the Mackenzie Shelf (Galand et al., 2006). The discrepancy between studies may be because of the use of different probes, primers or extraction methods to detect or quantify Archaea (Casamayor et al., 2002). A standardized approach combining quantitative and qualitative methods, and covering a vast range of water masses would allow a more precise description of archaeal distributions in the Arctic.

An overview of archaeal clone distribution in the southern Beaufort Sea and Amundsen Gulf suggests that coastal water masses, influenced by particle laden river runoff, would be a more suitable habitat for group II Euryarchaeota (Galand et al., 2008b). Group IIa sequences found in the Pacific surface waters had high similarity to sequences retrieved from sediments, suggesting that the occurrence of this group is related to sediment and particle loads exported by Arctic rivers to the adjacent Beaufort Sea. A recent metagenomic study showed that the genome of group II Euryarchaeota seemed enriched in putative anaerobic respiration components, suggesting that anaerobic pathways for energy production are present in the group (Martin-Cuadrado et al., 2008). In the light of this finding and these data showing abundant group IIa sequences in coastal waters, we speculate that group IIa Euryarchaeota could be involved in the anaerobic degradation of organic matter coming from river runoff. The most abundant group II sequences found in the deep-water masses (cluster b and c) were distinct from the one detected in surface waters. The presence of different group II sequences in different environments may indicate that within group II Euryarchaeota ecological differences may favor different phylogenetic clusters or even different metabolic functions within the separate clusters.

Group IV Euryarchaeota were mainly found in deep Atlantic water, but always at very low abundance. Group IV was originally described from the Antarctic Polar Front, and further detected in the North Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea (López-García et al., 2001). Group IV has always been detected in deep-water masses with the exception of one clone retrieved from upper Arctic mixed layers (Bano et al., 2004). Our results confirm group IV as specifically inhabiting deep-water masses at a low abundance. Nothing is known at present about the metabolism of this group.

Finally, archaeal communities in the Arctic Ocean had a relatively low diversity, as the rarefaction curves reached an asymptote with a maximum estimated richness of 344–865 OTUs at a 97% level. Those results are in agreement with earlier reports, indicating that Archaea are generally less diverse than Bacteria, as shown through clone library surveys (Aller and Kemp 2008) and pyrosequencing of hydrothermal vents samples (Huber et al., 2007).

In summary, we have shown that archaeal assemblages from Arctic surface layers were different from those in deep-water masses, with great differences in the amount of group II and group III Euryarchaeota. However, there were also large differences between the composition of the coastal Beaufort Sea community (sample ACB_0011) and the other samples from Pacific surface water. MGI was essentially absent from the ACB_0011 community, in which a single group II tag represented most of the sequences (85%). The difference in community composition was reflected in the physicochemical characteristics of the water. The warmer, less saline water of ACB_0011 indicates the intrusion of a different water mass at that depth. The predominance of one single sequence tag may also indicate a bloom triggered, for example, by higher concentration of phytoplankton as indicated by high chlorophyll a values (Table 1).

For the first time, we successfully applied massively parallel tag sequencing to describe the taxonomic composition of archaeal communities. Our data revealed unique assemblages of Archaea in the Arctic Ocean, with group III Euryarchaeota dominating the deep Atlantic water mass. Those results open new perspectives on the possible competition between group III Euryarchaeota and MGI Crenarchaeota for putative energy sources such as ammonia oxidation. We also showed that the distribution of archaeal diversity varied with water masses, suggesting biogeographical traits for archaeal communities in the Arctic. Pyrosequencing gave a high coverage of these assemblages and offered a good taxonomical assignment for most of the groups as shown by the general agreement between the present V6 data and earlier clone library descriptions. The methodological approach had, however, some limitation, as the most abundant MGI tag could not be precisely affiliated. The low taxonomical resolution for that particular group is probably because of the presence of a more conserved V6 regions.

References

Agogue H, Brink M, Dinasquet J, Herndl GJ . (2008). Major gradients in putatively nitrifying and non-nitrifying Archaea in the deep North Atlantic. Nature 456: 788–791.

Aller JY, Kemp PF . (2008). Are Archaea inherently less diverse than bacteria in the same environments? FEMS Microbiol Ecol 65: 74–87.

Arrigo KR . (2005). Marine microorganisms and global nutrient cycles. Nature 437: 349–355.

Auguet JC, Casamayor EO . (2008). A hotspot for cold crenarchaeota in the neuston of high mountain lakes. Environ Microbiol 10: 1080–1086.

Bano N, Ruffin S, Ransom B, Hollibaugh JT . (2004). Phylogenetic composition of Arctic Ocean archaeal assemblages and comparison with Antarctic assemblages. Appl Environ Microbiol 70: 781–789.

Casamayor EO, Massana R, Benlloch S, Ovreas L, Diez B, Goddard VJ et al. (2002). Changes in archaeal, bacterial and eukaryal assemblages along a salinity gradient by comparison of genetic fingerprinting methods in a multipond solar saltern. Environ Microbiol 4: 338–348.

Clementino MM, Fernandes CC, Vieira RP, Cardoso AM, Polycarpo CR, Martins OB . (2007). Archaeal diversity in naturally occurring and impacted environments from a tropical region. J Appl Microbiol 103: 141–151.

Cole JR, Wang Q, Cardenas E, Fish J, Chai B, Farris RJ et al. (2009). The Ribosomal Database Project: improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 37: D141–D145.

DeLong EF, Preston CM, Mincer T, Rich V, Hallam SJ, Frigaard NU et al. (2006). Community genomics among stratified microbial assemblages in the ocean′s interior. Science 311: 496–503.

Edgar RC . (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 1792–1797.

Felsenstein J . (2004). PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package). version 3 Distributed by the author. Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle.

Francis CA, Beman JM, Kuypers MMM . (2007). New processes and players in the nitrogen cycle: the microbial ecology of anaerobic and archaeal ammonia oxidation. ISME J 1: 19–27.

Frigaard NU, Martinez A, Mincer TJ, DeLong EF . (2006). Proteorhodopsin lateral gene transfer between marine planktonic Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 439: 847–850.

Fuhrman JA, Davis AA . (1997). Widespread Archaea and novel bacteria from the deep sea as shown by 16S rRNA gene sequences. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 150: 275–285.

Galand PE, Lovejoy C, Vincent WF . (2006). Remarkably diverse and contrasting archaeal communities in a large arctic river and the coastal Arctic Ocean. Aqua Microbial Ecol 44: 115–126.

Galand PE, Lovejoy C, Pouliot J, Garneau ME, Vincent WF . (2008a). Microbial community diversity and heterotrophic production in a coastal arctic ecosystem: A Stamukhi lake and its source waters. Limnol Oceanogr 53: 813–823.

Galand PE, Lovejoy C, Pouliot J, Vincent WF . (2008b). Heterogeneous archaeal communities in the particle-rich environment of an arctic shelf ecosystem. J Marine Syst 74: 774–782.

Galand PE, Lovejoy C, Hamilton AK, Ingram RG, Pedneault E, Carmack E . (2009). Archaeal diversity and a gene for ammonia oxidation are coupled to oceanic circulation. Environ Microbiol doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01822.x.

Garneau ME, Roy S, Lovejoy C, Gratton Y, Vincent WF . (2008). Seasonal dynamics of bacterial biomass and production in a coastal arctic ecosystem: Franklin Bay, western Canadian Arctic. J Geophys. Res 113: C07S91, doi:10.1029/2007JC004281.

Hallam SJ, Konstantinidis KT, Putnam N, Schleper C, Watanabe YI, Sugahara J . (2006a). Genomic analysis of the uncultivated marine crenarchaeote Cenarchaeum symbiosum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 18296–18301.

Hallam SJ, Mincer TJ, Schleper C, Preston CM, Roberts K, Richardson PM et al. (2006b). Pathways of carbon assimilation and ammonia oxidation suggested by environmental genomic analyses of marine Crenarchaeota. PLoS Biol 4: e95.

Herndl GJ, Reinthaler T, Teira E, van Aken H, Veth C, Pernthaler A et al. (2005). Contribution of Archaea to total prokaryotic production in the deep Atlantic Ocean. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 2303–2309.

Huber JA, Mark Welch DB, Morrison HG, Huse SM, Neal PR, Butterfield DA et al. (2007). Microbial population structures in the deep marine biosphere. Science 318: 97–100.

Huse S, Huber J, Morrison H, Sogin M, Welch D . (2007). Accuracy and quality of massively parallel DNA pyrosequencing. Genome Biol 8: R143.

Jones EP, Swift JH, Anderson LG, Lipizer M, Civitarese G, Falkner KK et al. (2003). Tracing Pacific water in the North Atlantic Ocean. J Geophys Res-Oceans 108: 1–10.

Karner MB, DeLong EF, Karl DM . (2001). Archaeal dominance in the mesopelagic zone of the Pacific Ocean. Nature 409: 507–510.

Kirchman DL, Elifantz H, Dittel AI, Malmstrom RR, Cottrell MT . (2007). Standing stocks and activity of Archaea and Bacteria in the western Arctic Ocean. Limnol Oceanogr 52: 495–507.

Konneke M, Bernhard AE, de la Torre JR, Walker CB, Waterbury JB, Stahl DA . (2005). Isolation of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing marine archaeon. Nature 437: 543–546.

Lam P, Jensen MM, Lavik G, McGinnis DF, Muller B, Schubert CJ . (2007). Linking crenarchaeal and bacterial nitrification to anammox in the Black Sea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 7104–7109.

López-García P, Moreira D, López-López A, Rodríguez-Valera F . (2001). A novel haloarchaeal-related lineage is widely distributed in deep oceanic regions. Environ Microbiol 3: 72–78.

Malmstrom RR, Straza TRA, Cottrell MT, Kirchman DL . (2007). Diversity, abundance, and biomass production of bacterial groups in the western Arctic Ocean. Aqua Microbial Ecol 47: 45–55.

Martin-Cuadrado AB, Lopez-Garcia P, Alba JC, Moreira D, Monticelli L, Strittmatter A . (2007). Metagenomics of the deep Mediterranean, a warm bathypelagic habitat. PLoS ONE 2: e914.

Martin-Cuadrado AB, Rodriguez-Valera F, Moreira D, Alba JC, Ivars-Martinez E, Henn MR et al. (2008). Hindsight in the relative abundance, metabolic potential and genome dynamics of uncultivated marine archaea from comparative metagenomic analyses of bathypelagic plankton of different oceanic regions. ISME J 2: 865–886.

Massana R, DeLong EF, Pedros-Alio C, Murray AE, Preston CM . (2000). A few cosmopolitan phylotypes dominate planktonic archaeal assemblages in widely different oceanic provinces. Appl Environ Microbiol 66: 1777–1787.

McLaughlin FA, Carmack EC, Macdonald RW, Melling H, Swift JH, Wheeler PA et al. (2004). The joint roles of Pacific and Atlantic-origin waters in the Canada Basin, 1997–1998. Deep Sea Res Pt I 51: 107–128.

Mehta MP, Huber JA, Baross JA . (2005). Incidence of novel and potentially archaeal nitrogenase genes in the deep Northeast Pacific Ocean. Environ Microbiol 7: 1525–1534.

Mincer TJ, Church MJ, Taylor LT, Preston C, Karl DM, DeLong EF . (2007). Quantitative distribution of presumptive archaeal and bacterial nitrifiers in Monterey Bay and the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. Environ Microbiol 9: 1162–1175.

Nusch E . (1980). Comparison of different methods for chlorophyll and phaeopigment determination. Arch Hydrobiol Beih 14: 14–36.

Pouliot J, Galand PE, Lovejoy C, Vincent WF . (2009). Vertical structure of archaeal communities and the distribution of ammonia monooxygenase A gene variants in two meromictic High Arctic lakes. Environ Microbiol 11: 687–699.

Pruesse E, Quast C, Knittel K, Fuchs BM, Ludwig W, Peplies J et al. (2007). SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res 35: 7188–7196.

Rudels B, Jones PE, Schauer U, Eriksson P . (2004). Atlantic sources of the Arctic Ocean surface and halocline waters. Polar Res 23: 181–208.

Schloss PD, Handelsman J . (2005). Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 1501–1506.

Sogin ML, Morrison HG, Huber JA, Welch DM, Huse SM, Neal PR et al. (2006). Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the under explored “rare biosphere”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 12115–12120.

Tang CCL, Ross CK, Yao T, Petrie B, DeTracey BM, Dunlap E . (2004). The circulation, water masses and sea-ice of Baffin Bay. Prog Oceanogr 63: 183–228.

Teira E, van Aken H, Veth C, Herndl GJ . (2006). Archaeal uptake of enantiomeric amino acids in the meso- and bathypelagic waters of the North Atlantic. Limnol Oceanogr 51: 60–69.

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ . (1994). CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22: 4673–4680.

Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR . (2007). Naive bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 5261–5267.

Wuchter C, Abbas B, Coolen MJL, Herfort L, van Bleijswijk J, Timmers P et al. (2006). Archaeal nitrification in the ocean. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 12317–12322.

Yamamoto-Kawai M, Carmack E, McLaughlin F . (2006). Nitrogen balance and Arctic throughflow. Nature 443: 43.

Acknowledgements

P E Galand is supported by a Marie Curie grant (CRENARC MEIF-CT-2007–040247). EO Casamayor was supported by a Spanish grant CGL2006–12058-BOS, and D L Kirchman by NSF OPP ARC-0632233. C Lovejoy would like to acknowledge the support of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council, Canada (NSERC) Special Research Opportunity Fund. We thank C Pedros-Alio for support during CASES. Deep Arctic samples were collected by K Scarcella and E Didierjean, and we thank the Chief Scientist, Officers and Crew of the CCGS Louis St Laurent and support from Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Tag sequencing was supported by a Keck foundation grant to M Sogin and L Ameral Zettler. This is a contribution to the International Census of Marine Microbes (ICOMM).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Galand, P., Casamayor, E., Kirchman, D. et al. Unique archaeal assemblages in the Arctic Ocean unveiled by massively parallel tag sequencing. ISME J 3, 860–869 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2009.23

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2009.23

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Vertical distribution and phylogenetic characterization of marine Archaea in the western subarctic Pacific

Marine Development (2024)

-

Vertical segregation and phylogenetic characterization of archaea and archaeal ammonia monooxygenase gene in the water column of the western Arctic Ocean

Extremophiles (2023)

-

Applying the concept of liquid biopsy to monitor the microbial biodiversity of marine coastal ecosystems

ISME Communications (2022)

-

Archaeal diversity in the seawater of Changjiang River estuary reveals its adaptability to bottom seawaters

Journal of Oceanology and Limnology (2022)

-

High diversity of planktonic prokaryotes in Arctic Kongsfjorden seawaters in summer 2015

Polar Biology (2021)