Abstract

Deep marine subsurface sediments represent a novel archaeal biosphere with unknown physiology; the sedimentary subsurface harbors numerous novel phylogenetic lineages of archaea that are at present uncultured. Archaeal 16S rRNA analyses of deep subsurface sediments demonstrate their global occurrence and wide habitat range, including deep subsurface sediments, methane seeps and organic-rich coastal sediments. These subsurface archaeal lineages were discovered by PCR of extracted environmental DNA; their detection ultimately depends on the specificity of the archaeal PCR 16S rRNA primers. Surprisingly high mismatch frequencies for some archaeal PCR primers result in amplification bias against the corresponding archaeal lineages; this review presents some examples. Obviously, most archaeal 16S rRNA PCR primers were developed either before the discovery of these deep subsurface archaeal lineages, or without taking their sequence variants into account. PCR surveys with multiple primer combinations, revision and updates of primers whenever possible, and increasing use of PCR-independent methods in molecular microbial ecology will contribute to a more comprehensive view of subsurface archaeal communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Deep marine subsurface sediments are one of the most extensive microbial habitats on Earth. Marine sediments cover more than two-thirds of the Earth's surface, and microbial cells and microbial activity (bacteria and archaea) appear to be widespread in these sediments. As a general rule, microbial cell counts in subsurface sediments decreases logarithmically with depth, most likely as a result of decreasing organic carbon quality and availability in aged, deeply buried sediments (Parkes et al., 2000). Sufficient cell count data are available to allow initial quantitative assessments of subsurface microbial populations in relation to Earth's overall biomass. The microbial cells of subseafloor sediments have been estimated to constitute 1/2–5/6 of Earth's microbial biomass (Whitman et al., 1998) and 1/10–1/3 of Earth's total living biomass (Whitman et al., 1998; Parkes et al., 2000). These deep subsurface populations are at least to some extent metabolically active. Small subunit (16S) rRNA-dependent counts of bacterial and archaeal cells (Schippers et al., 2005; Biddle et al., 2006) and analysis of intact membrane lipids (Sturt et al., 2004; Biddle et al., 2006) provide multifaceted evidence of active microbial populations in deep subsurface sediments on a global scale.

Investigating the energy and carbon sources and the metabolism of these active subsurface bacteria and archaea, and documenting their community composition in different habitats and geochemical settings, remain current challenges of deep subsurface microbiology. Prokaryotic activity, in the form of sulfate reduction and/or methanogenesis, occurs in deep sediments throughout the world's oceans (D'Hondt et al., 2002). Sulfate, the most highly concentrated electron acceptor in seawater and consequently the dominant electron acceptor for anaerobic metabolism in marine sediments (Jørgensen, 1982), penetrates deep marine subsurface sediments on a scale of tens to hundreds of meters, depending on organic carbon availability. Comparative studies of organic-rich and organic-poor deep marine subsurface sediments have demonstrated the effects of electron donor and electron acceptor limitation (D'Hondt et al., 2002, 2004). In organic-rich coastal sediments, heterotrophic microbial populations deplete sulfate and other electron acceptors quickly within a few meters of the sediment–water interface; the increasing scarcity of electron acceptors imposes energetic constraints on deep subsurface microbial communities. In contrast, the entire sediment column from seawater interface to basement basalt can be permeated by sulfate and other electron acceptors in organic-poor sediments with low microbial population density and activity, Here, low concentrations of organic carbon substrates limit microbial abundance and activity (D'Hondt et al., 2002, 2004).

Are there specific microorganisms that thrive in the sedimentary subsurface under conditions of permanent, two-pronged energy limitation, limited organic carbon or electron acceptor availability? This review focuses on archaea in the deep marine sedimentary subsurface. The archaeal communities in marine subsurface sediments are particularly interesting for the following reasons: (1) They consist almost exclusively of uncultured, mutually exclusive phylogenetic lineages that have been discovered only within the last few years (for example, see the seminal study by Vetriani et al., 1999); (2) archaea are most likely the dominant microbial domain of the deep marine subsurface. Often, archaeal cells occur in higher numbers than bacterial cells, independently confirmed by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) counts and lipid quantification (Biddle et al., 2006) and contesting earlier claims to the contrary (Schippers et al., 2005). Metagenomic surveys of the deep subsurface also support dominance of archaea over bacteria (Biddle, 2006). (3) The diverse range of archaeal metabolisms and extremophilic physiologies has evolved as adaptations to energy limitation in difficult or inhospitable environments (Valentine, 2007), such as the deep marine subsurface; (4) As far as we know, production and consumption of methane, two of the most widespread biogeochemical processes in subsurface sediments, are mediated strictly by members of the archaeal domain.

Here, we review the major archaeal phylogenetic lineages that occur typically in the deep marine sedimentary subsurface, and update a more general review on subsurface microbiology (Teske, 2006) by digging deeper into the diversity of subsurface archaea and their detection. The first section of this review is intended as a guide through the maze of novel archaeal phylogenetic lineages in the subsurface, illustrated by a 16S rRNA phylogeny of these uncultured archaeal subsurface lineages and selected cultured archaea (Figure 1). Reliable identification of new archaeal 16S rRNA clones, including recognition of their phylogenetic affiliation to specific archaeal lineages, is essential for understanding the habitat range and environmental preferences of these uncultured archaea. Many archaeal phylotypes in environmental sequencing surveys are not properly identified or assigned to specific archaeal lineages in the original publications (examples in Coolen et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2005; Stein et al., 2002); the synonyms and equivalent designations that different research teams have introduced for one and the same lineage only increase the confusion.

Phylogenetic tree of eury- and crenarchaeal groups discussed in the text. The tree was constructed from an alignment of >600 unambiguously aligned base pairs using Jukes–Cantor for distance calculations followed by neighbor-joining (Sørensen and Teske, 2006). The stability of the branching pattern was evaluated by bootstrapping (1000 replicates). The resulting bootstrap values are indicated at each node in the tree.

In the second section, we re-examine the molecular tools—PCR primers—that were instrumental in detecting this new world of archaeal subsurface lineages. We highlight detection biases and recommend solutions for reducing detection bias, allowing more comprehensive archaeal population analyses.

We note that not only the microbial nomenclature is currently in flux, but also the concept of ‘deep subsurface’. A total of 3–4 m sediment depth in coastal sediments is not considered ‘deep subsurface’, although many bacteria and archaea that are characteristic for much deeper sediment layers are readily detectable at these moderate depths (Wilms et al., 2006a, 2006b; Parkes et al., 2007). On the other hand, many ‘deep subsurface’ sediment samples obtained by deep subsurface drilling are within 1–2 m of the sediment surface; some geochemical analyses, for example nitrate porewater gradients, focus by necessity on near-surface sediment layers (D’Hondt et al., 2004). As a guideline for defining the deep subsurface by microbial ecological criteria, we suggest that sediment layers with distinct microbial communities that lack a microbial imprint of water column communities, should be considered deep subsurface. In other words, the sediment horizon where water column bacterial and archaeal communities are fading out, and solely sediment-typical bacterial and archaeal communities are remaining, defines the upper boundary of the deep subsurface; the position of this boundary would be locally variable. The sediment layers between this boundary and the sediment–water interface would be considered shallow subsurface, and they would be characterized by mixed water column and sediment communities of archaea and bacteria.

Archaeal subsurface lineages

The Marine Benthic Group B (MBG-B)

MBG-B Archaea were proposed by Vetriani et al. (1999); the group is synonymous with the Deep-Sea Archaeal Group (DSAG) as defined by Inagaki et al. (2003). MBG-B archaea represent one of the dominant archaeal lineages in clone libraries of archaeal 16S rRNA and occur in a wide range of sampling sites and sediment types. They were originally found in surficial sediments on the continental slope and abyssal plain of the North Atlantic (Vetriani et al., 1999) and at hydrothermal vent sites (Takai and Horikoshi, 1999). Members of the DSAG/MBG-B Archaea have been detected in a wide range of anoxic, marine environments, including methane-consuming Black Sea microbial mats and carbonate reefs (Knittel et al., 2005), surficial methane seep sediments in the Gulf of Mexico (Lloyd et al., 2006), deep-sea sediments from the Okhotsk Sea (Inagaki et al., 2003), hydrate-containing sediments of the Pacific Margin and in the Nankai Trough (Reed et al., 2002; Newberry et al., 2004; Inagaki et al., 2006), organic-poor subsurface sediments from the Equatorial Pacific (Sørensen et al., 2004) and in diverse hydrothermal vent sites (Takai and Horikoshi, 1999; Reysenbach et al., 2000; Teske et al., 2002). MBG-B Archaea are not limited to deep-sea marine sediments, methane seeps and vents, but occur in coastal, intertidal sediments as well (Kim et al., 2005).

Published phylogenies show the DSAG/MBG-B Archaea as a basal group next to Euryarchaeota (Reed et al., 2002) or more frequently to the Crenarchaeota (Takai and Horikoshi, 1999; Vetriani et al., 1999; Takai et al., 2001; Inagaki et al., 2003; Sørensen et al., 2004; Knittel et al., 2005). Highly conserved, phylum-specific ‘signature’ 16S rRNA nucleotide positions show a mix of eury- and crenarchaeotal signature nucleotides (Vetriani et al., 1999). Most deeply-branching DSAG/MBG-B Archaea were found in hydrothermal vents, whereas the uppermost branches (the ‘crown’) of the tree consists of phylotypes occurring in cold sediments and carbonates (Teske, 2006) (Figure 1).

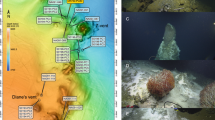

DSAG/MBG-B Archaea are not just present, but they are metabolically active in the deep subsurface, and their 16S rRNA can be isolated in sufficient amounts from deep marine subsurface sediments to permit reverse transcription, cloning and sequencing. 16S rRNA and 16S rRNA gene surveys give compatible results for subsurface sediments that have been examined with both approaches. A good example is ODP Site 1230 in the Peru Trench; the methane–sulfate transition layer harbors metabolically active DSAG/MBG-B Archaea that are detectable by reverse 16S rRNA transcription (Biddle et al., 2006) as well as by DNA isolation and PCR (Inagaki et al., 2006). At ODP Site 1227 on the Peru Margin, active DSAG/MBG-B Archaea were found to dominate a narrow sediment horizon sandwiched between other archaeal populations within the broad methane–sulfate transition zone (Figure 2); interestingly, this DSAG/MBG-B layer was not detected in 16S rDNA surveys (Inagaki et al., 2006). These results suggest that the MBG-B Archaea may benefit directly or indirectly from anaerobic methane oxidation in marine sediments (Sørensen and Teske, 2006). Another link to methane was found in a 16S rDNA sequencing survey of four eastern Pacific continental margin subsurface sediments (Inagaki et al., 2006); here, DSAG/MBG-B Archaea dominated sediment columns that contained methane hydrates; whereas other archaea dominated the non-hydrate sediments (Inagaki et al., 2006).

Stratified populations of DSAG/The Marine Benthic Group B (MBG-B) and other archaea in Peru Margin subsurface sediments of ODP Site 1227, as detected by reverse transcription and sequencing of extracted 16S rRNA. (a) Sulfate (empty circles) and methane (black triangles) porewater profiles. The methane concentrations are multiplied by factor 10. (b) Relative amounts of 16S rRNA and 16S rRNA genes (rDNA) in different sediment depths. For 16S rRNA, a value of 1 corresponds to the detection limit. The 16S rRNA genes (rDNA) were quantified by Q-PCR (open circles; redrawn from Schippers et al., 2005). Here, the amount of rDNA (black squares) found at 37.75 m.b.s.f. (meter below the seafloor) was normalized to a value of 1. (c) Phylogenetic composition of archaeal clone libraries from reverse-transcribed 16S rRNA from each depth. The sample from 37.75 m.b.s.f. was extracted twice, and PCR-amplified three times, resulting in three clone libraries (see bars marked by oval bracket). The first extract was amplified using ARC915R (first bar); the second extract was amplified using two primer sets, ARC915R (second bar) or ARC519R (third bar) in combination with the same forward primer, ARC8f. At the right end of the third bar, the short segment in white (Other) represents the elusive AAG Archaea that remain undetected with other PCR primer combinations. Figure modified from Sørensen and Teske (2006).

However, DSAG/MBG-B Archaea are clearly not limited to methane–sulfate transition zones in the manner of anaerobic, sulfate-dependent methane-oxidizing archaea, but they occur almost anywhere in methanogenic, anaerobic sediments. In the eastern Pacific continental margin subsurface sediments, DSAG/MBG-B Archaea dominated extensive sediment columns (ODP Sites 1230, 1244, 1245 and 1251) that contained methane hydrates in highly reduced, sulfate-free sediments, whereas other archaeal groups dominated the non-hydrate sediments (Inagaki et al., 2006). Stable carbon isotopic signatures of archaeal phospholipids and archaeal cell biomass from ODP Sites 1227 and 1230 showed that buried organic carbon, not methane, is the primary carbon source for archaeal communities at methane–sulfate interface sediments that yielded mostly DSAG/MBG-B archaeal clones (Biddle et al., 2006). Assimilation of buried organic carbon and lack of assimilation of methane-derived carbon would be consistent with three types of metabolism: heterotrophic fermentation of buried biomass; assimilation of organic carbon sources while performing methane oxidation solely for energy generation (Biddle et al., 2006); and—a speculative possibility—microbial ethanogenesis by acetate reduction, a recently proposed, thermodynamically feasible and microbiologically mediated process in deep subsurface sediments (Hinrichs et al., 2006).

So far, microscopy of archaeal cells in deep subsurface sediments using FISH techniques has detected individual cells distributed in the sediment, but no biofilms or cell clusters (MauClaire et al., 2004; Schippers et al., 2005; Biddle et al., 2006). In near-surface habitats, growth in aggregates is clearly possible. DSAG/MBG-B Archaea have been visualized by rRNA-targeted FISH hybridization in Black Sea microbial mats growing on carbonate reefs; in this habitat, they appear as small (<1 μm), coccoid or slightly elongated cells, growing in clusters (Knittel et al., 2005).

The Ancient Archaeal Group (AAG) and The Marine Hydrothermal Vent Group (MHVG)

The AAG and MHVG archaea are deeply branching, recently found archaeal lineages that share the vent and subsurface habitat of the DSAG/MBG-B Archaea. Both lineages are not subsumed under any other eury- or crenarchaeotal lineage (Figure 1). Published phylogenies (Takai and Horikoshi, 1999; Inagaki et al., 2003) indicate that these groups originate in the deep phylogenetic radiation near the base of the Crenarchaeota. The MHVG Archaea were originally detected at hydrothermal vent sites near Japan (clone pMC2A15; Takai and Horikoshi, 1999) and were defined as a phylogenetic lineage after finding closely related phylotypes in cold sediments in the Okhotsk Sea (Inagaki et al., 2003). AAG phylotypes were originally found at hydrothermal vent sites near Japan (Takai and Horikoshi, 1999), and recently in cold, organic-rich Peru Margin subsurface sediments at ODP Site 1227 (Sørensen and Teske, 2006). The Peru Margin phylotypes were obtained by reverse transcription of extracted rRNA, indicating that these archaea harbor intact 16S rRNA and therefore represent a living population in the subsurface (Sørensen and Teske, 2006). Since both the AAG and MHVG have so far only been detected in a few studies, their biogeographical distribution and habitat preference remain poorly understood.

The Miscellaneous Crenarchaeotic Group (MCG)

The MCG archaea are one of the predominant archaeal groups in 16S rRNA clone libraries obtained from marine deep subsurface sediments. In contrast to the marine benthic DSAG/MBG-B group, the MCG Archaea have a much wider habitat range that includes terrestrial and marine, hot and cold, surface and subsurface environments (Teske, 2006). Phylotypes of the MCG from the deep terrestrial subsurface in South African goldmines and from other terrestrial habitats constituted the ‘Terrestrial Miscellaneous Crenarchaeotic Group’ (Takai et al., 2001). After the discovery of marine phylotypes, the group was renamed ‘Miscellaneous Crenarchaeotic Group’ (Inagaki et al., 2003). The label ‘miscellaneous’ appears to reflect the difficulty to categorize the wide terrestrial and marine habitat range of this group, including terrestrial palaeosol (Chandler et al., 1998), freshwater lakes (Stein et al., 2002), surficial marine sediments (Vetriani et al., 1999), diverse marine subsurface sediments (Coolen et al., 2002; Reed et al., 2002; Inagaki et al., 2003, 2006; Newberry et al., 2004; Parkes et al., 2005; Biddle et al., 2006; Sørensen and Teske, 2006), terrestrial hot springs (Yellowstone; Barns et al., 1996) and marine hydrothermal vents (Guaymas Basin; Teske et al., 2002). At present, no other deep subsurface archaeal lineage has such a diversified habitat range. The rapidly growing numbers of MCG clones from different environments, and the high intragroup phylogenetic depth of the MCG Archaea necessitated dividing this unusually large group with hundreds of clones into smaller, more manageable subgroups (PM-1 to PM-8; Parkes et al., 2005; MCG-1 to MCG-4; Sørensen and Teske, 2006). Additional subgroups of the MCG Archaea include the Marine Benthic Group C, defined by Vetriani et al., (1999), and the NT-A3 and NT-A4 groups from deep marine hydrate-bearing sediments (Reed et al., 2002) (Figure 1). To alleviate this confusing situation and to clear up the nomenclature, a thorough re-analysis of the MCG Archaea for potential links between phylogenetic structure and habitat characteristics is clearly overdue.

Beyond mere presence, MCG Archaea are metabolically active in the deep subsurface; 16S rRNA and rDNA analyses of deep subsurface sediments from the same locations have yielded largely consistent and compatible results. At ODP Site 1229 on the Peru Margin, MCG Archaea dominate archaeal clone libraries based on extracted and PCR-amplified 16S rRNA genes (Parkes et al., 2005), and of reverse-transcribed 16S rRNA (Biddle et al., 2006). At ODP Site 1227 on the Peru Margin, MCG Archaea were abundant in 16S rRNA gene clone libraries from all depths (Inagaki et al., 2006) and they dominated the reverse-transcribed 16S rRNA pool in all sediment layers except the DSAG/MBG-B horizon discussed above (Sørensen and Teske, 2006).

Carbon-isotopic signatures of archaeal cells and polar lipids from MCG-dominated sediment horizons indicate utilization of buried organic carbon by the archaeal community (Biddle et al., 2006). Interestingly, the MCG Archaea dominate in archaeal clone libraries from nutrient-rich sapropel layers or volcanic ash horizons embedded in sediment columns that consist otherwise of organic-poor hemipelagic carbonates and clays (Coolen et al., 2002; Inagaki et al., 2003). The DSAG/MBG-B Archaea did not show this conspicuous distribution pattern. These findings support the working hypothesis that MCG Archaea are heterotrophic anaerobes that utilize and assimilate complex organic substrates.

The Marine Group I (MG-I) Archaea

MG-I Archaea were originally identified by sequencing of environmental 16S rRNA genes from seawater (DeLong, 1992; Fuhrman et al., 1992). MG-I Archaea account for a major portion of all prokaryotic picoplankton in seawater (DeLong et al., 1994; Fuhrman and Ouverney, 1998; Karner et al., 2001). In the deep-sea water column below ca. 3000 m depth, MG-I Archaea constitute the majority of prokaryotic picoplankton (Karner et al., 2001). However, MG-I Archaea are also found in the marine sedimentary subsurface; they penetrate several meters into the seafloor at organic-poor open ocean sites in the Equatorial Pacific (ODP Site 1225; Teske, 2006) and in the Peru Basin (ODP Site 1231; Sørensen et al., 2004).

Functional gene surveys (Francis et al., 2005), cultivations and pure-culture study (Könneke et al., 2005) and whole-genome sequencing (Hallam et al., 2006a, 2006b) indicate that at least some members of the MG-I Archaea are aerobic, autotrophic ammonia oxidizers. The first cultured representative of the Marine Group I is an aerobic, chemolithoautotrophic, nitrifying archaeon that oxidizes ammonia to nitrite (Könneke et al., 2005). The ammonia monooxygenase genes of MG-I Archaea are ubiquitous in marine water column and surficial sediment (Francis et al., 2005). The habitat preference of MG-I Archaea for the surface layers of oxidized, organic-poor marine sediments is consistent with an aerobic metabolism and an ability to take up inorganic dissolved carbon and to fix carbon autotrophically (Pearson et al., 2001; Wuchter et al., 2003; Ingalls et al., 2006). The ability to assimilate amino acids indicates that autotrophy is not obligate (Ouverney and Fuhrman, 2000). Also, carbon-isotopic composition of MG-I archaeal lipids suggests some degree of organic carbon assimilation, perhaps in a mixotrophic metabolism (Ingalls et al., 2006).

MG-1 phylotypes found in subsurface sediments form several phylogenetic clusters distinct from the seawater representatives (Sørensen et al., 2004). The implications of this are not clear, but one possibility is that specialized groups of MG-1 Archaea tolerate the subsurface conditions well enough to persist and evolve in this environment. Therefore, MG-I archaeal clones should not be dismissed as seawater contaminants without examination for phylogenetic affinity to subsurface or sediment clusters. Independent contamination assays have to be carried out to exclude or to minimize and quantify seawater contamination of deep marine sediments (Smith et al., 2000; House et al., 2003; Lever et al., 2006). In some cases, deep subsurface MG-I clones fall into phylogenetic clusters of MG-I phylotypes from other unusual environments. For example, the MG-I phylotypes recovered from deep subsurface sediment of ODP Site 1230 (Inagaki et al., 2006) fall into the MG-I γ and δ subclades that consist of deep-water MG-I phylotypes recovered from bottom water near hydrothermal vent sites (Takai et al., 2004).

The South African Goldmine Euryarchaeotal Group (SAGMEG)

SAGMEG was originally discovered in the deep terrestrial subsurface, in South African goldmines (Takai et al., 2001), and was regarded as a terrestrial group of subsurface archaea. However, SAGMEG Archaea were next found in deep marine sediments containing methane hydrates in the Nankai Trough, here labeled NT-A1 group (Reed et al., 2002); in marine subsurface sediments in the Sea of Okhotsk (Inagaki et al., 2003), and repeatedly in marine sediments of the Peru Margin, at ODP Sites 1227 (Inagaki et al., 2006), 1228 and 1229 (Parkes et al., 2005; Webster et al., 2006). The SAGMEG Archaea have been detected by rRNA extraction, reverse transcription, cloning and sequencing, and therefore appear to be a metabolically active archaeal group in deep marine subsurface sediments (Sørensen and Teske, 2006); they are a part of the heterotrophic archaeal community in deep, anaerobic and methanogenic Peru Margin sediments at ODP Site 1227 (Biddle et al., 2006).

The Marine Benthic Groups A and D (MBG-A, MBG-D)

MBG-A and MBG-D have been detected in few samples and sites, and usually do not dominate deep subsurface clone libraries (Table 6). These crenarchaeotal groups were found in 16S rDNA surveys of push cores retrieved from surficial sediments (upper 30 cm) of the Atlantic continental slope and abyssal plain of offshore New England (Vetriani et al., 1999). Marine Benthic Group D is equivalent to Marine Group III, as defined by DeLong (1998), and overlaps with Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vent Group I (DHVE 1) (Takai and Horikoshi, 1999). Clones of these groups occur in deep subsurface sediments of Leg 201 (Parkes et al., 2005; Sørensen and Teske, 2006; Webster et al., 2006), and in surficial marine sediments from around the world (Knittel et al., 2005). The detection of MBG-D in reverse-transcribed 16S rRNA clone libraries from Sites 1227 and 1228 indicates that the group is metabolically active in subsurface environments.

MBG-A Archaea were found in ODP Site 1225 (Teske, 2006), and MBG-D Archaea were found in ODP Sites 1227 and 1230 (Inagaki et al., 2006). In contrast to MG-I Archaea, they were not detected in the water column and appear to be benthic, sediment-dwelling archaea. Interestingly, a clone of the MBG-A Archaea was found in enrichment cultures inoculated with Site 1230 sediment, and incubated under aerobic conditions at 10 °C (Biddle et al., 2005).

The Terrestrial Miscellaneous Euryarcheotal Group

TMEG was originally based on clones from South African gold mines and other terrestrial environments (Takai et al., 2001). At present, this group includes phylotypes from the terrestrial subsurface and soils, marine sediments and freshwater lakes; it forms a sister group to Marine Benthic Group D (Teske, 2006) and to the Marine Group II and III Archaea (DeLong, 1998) within the Thermoplasmatales (Figure 1). The habitat range of TMEG Archaea is therefore similarly wide as the MCG Archaea, spanning both aquatic and terrestrial sites.

The Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vent Euryarchaeotal Group 6

DHVE-6 was originally defined by Takai and Horikoshi (1999) as a hydrothermal vent lineage. Renamed Miscellaneous Euryarcharotic Group, it included clones from terrestrial soil and marine sediments (Takai et al., 2001), also from organic-poor marine subsurface sediments (Sørensen et al., 2004). Similar to TMEG, this group spans the terrestrial-marine divide.

Archaeal PCR primers and their biases

PCR is an extremely powerful technique used to identify microorganisms in the environment based on DNA or RNA extracts. The archaeal groups discussed in the previous section were all originally discovered by amplifying and characterizing DNA extracts from environmental samples, and most of the current knowledge concerning deep subsurface biogeography has been obtained by PCR-based techniques (for example, Inagaki et al., 2006). Unfortunately, a major limitation of PCR is that only phylotypes containing matching (or nearly matching) priming sites may be detected. To some degree, the effect of a single nucleotide mismatch on PCR amplification may be compensated by annealing temperature (for example, Ishii and Fukui, 2001) but with an increasing number of mismatches, the amplification efficiency will decrease. Application of primers that match only part of the archaeal population will therefore directly affect results by under-representing or excluding groups of archaea that have frequent mismatches. In the following section, we evaluate a number of archaeal 16S rRNA primers by comparing them to their respective annealing sites in representatives of archaeal groups from subsurface environments. The analysis reveals how some phylogenetic lineages of archaea have been missed by PCR due to primer mismatches, and how the relative proportion of archaeal groups in clone libraries may have been distorted by selective priming.

Primer mismatches

Frequently used internal PCR primers for archaeal 16S rRNA were compared to their respective annealing sites in a selection of over 550 sequences obtained from subsurface and deep-sea hydrothermal vent environments. The online Supplementary material contains the complete list of these sequences including Genbank accession numbers. The sequences of each of the primers tested and examples of studies where they have been employed are given in Table 1. Three of the primers, ARC344f (A) and (B) (Raskin et al., 1994) and ARC349F (Takai and Horikoshi, 2000), target a relatively conserved sequence of the archaeal 16S rRNA gene within helices H339 and H47 (helix numbering according to Comparative RNA Web; Cannone et al., 2002). Primer ARC349F was designed for taq-man based PCR quantification of archaeal populations in combination with probe ARC516 and reverse primer ARC806R (Takai and Horikoshi, 2000). Primers ARC519R and PARCH519F/R (Ovreas et al., 1997) target the highly conserved region within helices H505 and H511. PARCH519F/R is a shorter version of the universal probe suggested by Pace et al. (1986), and not specific to the archaea. Primers ARC915R and Ar9R (Jurgens et al., 1997) both specifically target the archaeal domain. The target region lies within helices H885 and H17 in the central part of the 16S rRNA molecule. Primer Ar9R is near identical to ARC927R (Kormas et al., 2003); the only difference is an additional C at the 3 terminus in Ar9. ARC915R is a slightly altered version of the primer UNIV915R (Zheng et al., 1996) that target specifically the archaea. Primer ARC915R and ARC958R (Helix H960; DeLong, 1992) have been the most commonly used reverse primers in studies of subsurface sediments, most often in combination with a primer targeting the extreme 5′-end of the archaeal 16S rRNA gene.

The frequencies of mismatches with each of these 10 primers within different phylogenetic groups of archaea are summarized in Table 2. Since potential PCR bias depends strongly on the nature of the detected mismatches, Table 3 gives also the average number of mismatching nucleotides per sequence. Deletions or insertions were counted as one mismatch regardless of the number of nucleotides involved. Values larger than 1.0 are in bold in Table 3. This is done in order to highlight phylogenetic groups that are likely to be underrepresented during PCR, but we emphasize that the threshold of 1.0 is arbitrary. Detected mismatches with primers ARC915R and ARC958R are further detailed in Tables 4 and 5. Similar tables for the other primers are given in Supplementary Tables S1–S8 of the online Supplementary material.

The most general primers were ARC519R and PARCH519F/R, matching 91 and 95% of our archaeal subsurface sequence database, respectively. Since primer PARCH519 is not specific to the archaea, primer ARC519R appears to be the most general of the archaeal primers that were tested. Probe ARC516 is longer than the two primers targeting the same region and it contains several mismatches within both the 3′ and the 5′ end. It matches 78% of the sequences (Table 2). Generally, these primers near position 519 had a low number of mismatching nucleotides in the target region of all the phylogenetic groups. Primer ARC806R matches 89% of the phylotypes included in the analysis. The average number of mismatching nucleotides was 0.2, which is almost as low as ARC519R. Several members of the DSAG/MBG-B archaea contained a large insert of varying length near the middle of the target region of primer ARC806R. The primers ARC915R and Ar9R match in total 66 and 69% of the archaeal phylotypes, and the average number of mismatching nucleotides were 0.5 and 0.9, respectively. Primer ARC958R matches in total 36% of the phylotypes, with an average of one mismatching nucleotide per sequence. Primers 344 (A) and (B) contain the highest number of mismatches (Table 3). Primer ARC344F (B) contains fewer degeneracies and is longer than both ARC344F (A) and ARC349F. As a result, it has a substantially higher overall frequency of mismatches than the two other primers targeting the same region.

The primer mismatches were not evenly distributed among the phylogenetic groups, as summarized in Tables 2 and 3. For example, primer ARC516 did not match any of the phylotypes affiliated with the MBG-D lineage, whereas there was a good match with all the other primers. Primers ARC915R and Ar9R both have frequent mismatches within the SAGMEG, MHVG and AAG lineages. Primer Ar9R matches only 15% of the DSAG phylotypes, largely due to a single mismatching adenine at the 3′ end of the target region (Supplementary Table S8). Primer ARC958R had a high frequency of mismatches with members of the AAG, DHVEG-6, DSAG, MG-1 and MHVG Archaea. On average, members of the AAG, DHVE-6 and MHVG Archaea had 2.0, 1.7 and 1.9 mismatches per sequence—more than 50 times the average number for the Haloarcula (0.03) and more than 8 times the number for the A/T/M cluster and the microbial genome database for comparative analysis archaea (0.2) (Table 3).

Evidence for primer bias

From the above, it is clear that most of the PCR primers considered here contain numerous and frequent mismatches with several of the most abundant phylogenetic groups found in subsurface environments. How might this have affected the phylogenetic composition of clone libraries? And what are the implications for estimates of abundance and diversity of archaea in subsurface environments?

The sites listed in Table 6 are so far the only subsurface sediments that have been examined at least twice independently using different PCR primers. Diverging clone library representation of specific archaeal groups may be a consequence of primer-related bias. The bold values in Table 6 highlight archaeal groups with diverging representation in clone libraries from the same sites. Phylotypes affiliated with SAGMEG were consistently less frequent in clone libraries obtained with ARC915R than with ARC958R; this effect can be seen in the clone libraries of Sites 1227 and 1229 (Table 6). Conversely, MBG-B/DSAG Archaea were less frequent when ARC958R rather than ARC915R was employed; this effect can be seen in the clone libraries of site 1227, and with caution, at Site 1230 (Table 6). Both these observations are consistent with the mismatch numbers listed in Tables 2 and 3.

DGGE results obtained with PARCH519R in combination with forward primer Saf341 (5′-CCT AYG GGG CGC AGC AGG-3′) suggest that SAGMEG Archaea are abundant at ODP Sites 1228 and 1229 while MCG Archaea were not detected at all (Table 6, the two DGGE columns for Sites 1228 and 1229). Is this result a consequence of an extreme selectivity of the PARCH519R primer, or is it the result of the forward primer Saf341? Only few mismatches were detected with primer PARCH519R in MCG or SAGMEG, but 90% of the MCG phylotypes contained mismatches within the overlap between ARC344F and Saf341 (5′-CCT AYG GGG CGC AGC AGG-3′; the overlap within Saf341 is italicized) (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). The poor representation of MCG Archaea during these two DGGE studies may thus be caused by a poor match with the forward primer Saf341. Naturally, such comparisons of independent studies are complicated by the fact that different protocols may have been employed during extraction and/or PCR. Furthermore, in some cases RNA rather than DNA was extracted and analyzed. However, the observations discussed above are consistent with the kind of primer bias that may be expected from Tables 2 and 3.

Taq-man based Q-PCR has been employed to quantify archaeal populations in several subsurface sediments (for example, Coolen et al., 2002; Schippers et al., 2005; Inagaki et al., 2006). Judging from clone libraries, archaeal populations at several of the ODP Sites investigated are dominated by members of the MCG Archaea (for example, Peru Margin Sire 1227). Primer ARC349F which was used during these quantifications matches less than 10% of the MCG Archaea and the average number of mismatching nucleotides is relatively high (1.4, Table 3). It thus seems likely that MCG-dominated archaeal populations have been underestimated due to inefficient primer annealing.

The most direct evidence for a primer-related exclusion of a phylogenetic group comes from Peru Margin Site 1227 (Figure 2; Sørensen and Teske, 2006). Two clone libraries were obtained from the same RNA extract using RT–PCR with primer ARC915R or ARC519R in combination with the same forward primer. Consistent with the frequency and gravity of mismatches (Tables 2 and 3), sequences affiliated with the AAG Archaea were detected only with primer ARC519R. Members of the AAG are unlikely to be amplified using either of the primers ARC915R or ARC958R since almost all the phylotypes contain four or more mismatches. The same is the case for the DHVE-6 Archaea as most of these sequences contain three or more mismatches with either of the two primers.

Implications: have we caught them all?

The observation that groups like the DHVE-6, MHVG and AAG contain numerous mismatches with almost all the primers tested in this study and are only rarely retrieved in 16S rRNA surveys, points to the possibility that significant and so far unsampled archaeal diversity may exist in deep subsurface environment. A case in point is the discovery of the nanoarchaea (Huber et al., 2002), whose 16S rRNA sequences became accessible only after design of novel terminal 16S rRNA primers (Hohn et al., 2002). A first step in revealing hidden diversity in subsurface sediments could be to employ new and improved primers. For example, omitting the final C and introducing a degeneracy (Y) at the eleventh position of primer Ar9R will correct most of its mismatches with members of the DSAG/MBG-B and SAGMEG lineages. Screening against the RDP database using <PROBE MATCH> indicates that this modified Ar9R primer is still sufficiently specific for the archaea, although some bacterial sequences, particularly members of the Mycoplasma, were targeted when allowing just a single mismatch. Even after these modifications, primer ARC915R contain mismatches with most of the AAG and MHVG sequences. These can be corrected by introducing more degeneracies (positions 5 and 12), but only at the expense of less specificity.

The design of new primers as well as the systematic use of several different primer combinations may improve the chances of sampling the full diversity of subsurface archaea. Ultimately, alternative methods that do not depend on the design and employment of oligonucleotide primers may reveal to what degree cloning and sequencing of PCR products gives a representative picture of microbial biodiversity in subsurface sediments. For example, strand displacement amplification of environmental DNA (reviewed in Hutchinson et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2006) can generate sufficient amounts of DNA for further sequence analysis from DNA-limited sediment samples (Raghunathan, 2005; Abulencia et al., 2006). The method can be combined with highly efficient pyrosequencing of deep subsurface genomic DNA (Biddle, 2006). Isotopic and genomic methods could target single phylotypes by flow cytometry, and open new possibilities for a better understanding of the uncultivated subseafloor microbial components (Eek et al., 2007; Podar et al., 2007). Novel archaea that lack natural reservoirs where they occur in high densities, could be enriched using small-scale culture enrichments and physical cell separation and sorting (Kalyuzhnaya et al., 2006). Thus, a much greater proportion of the microbial world would be in reach for genomic and functional gene analyses; the recently postulated ‘Rare Biosphere’ would become accessible (Sogin et al., 2006).

Deep subsurface sediments are the spatially largest habitat for microorganisms on Earth and play an important role in the global carbon cycle. It is also one of the least understood microbial systems on Earth. Although preliminary insights into the biogeography of archaea in this environment have been revealed by amplification and characterization of DNA and RNA, the factors that control the distribution and function of prokaryotes in the subsurface remain poorly understood. Future studies, PCR-based as well as PCR independent, will improve the understanding of this vast habitat and help further integrate the phylogenetic and biogeochemical patterns observed.

References

Abulencia CB, Wyborski DL, Garcia JA, Podar M, Chen W, Chang SH et al. (2006). Environmental whole-genome amplification to access microbial populations in contaminated sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 3291–3301.

Barns SM, Delwiche CF, Palmer JD, Pace NR . (1996). Perspectives on archaeal diversity, thermophily and monophyly from environmental rRNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 9188–9193.

Biddle JF . (2006). Microbial populations and processes in deeply buried marine sediments. PhD thesis, Pennsylvania State University.

Biddle JF, House CH, Brenchley JE . (2005). Enrichment and cultivation of microorganisms from sediment from the slope of the Peru Trench (ODP site 1230). In: Jørgensen BB, D'Hondt SL, Miller DJ (eds). Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, 201 [Online]. Available from World Wide Web: <http://www-odp.tamu.edu-/publications-201_SR/107107.htm> [Cited 2007-07-07].

Biddle JF, Lipp JS, Lever MA, Lloyd KG, Sørensen KB, Anderson R et al. (2006). Heterotrophic archaea dominate sedimentary subsurface ecosystems off Peru. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 3846–3851.

Brosius J, Dull TJ, Sleeter DD, Noller HF . (1981). Gene organization and primary structure of a ribosomal RNA operon from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol 148: 107–127.

Cannone JJ, Subramanian S, Schnare MN, Collett JR, D'Souza LM, Du Y et al. (2002). The Comparative RNA Web (CRW) Site: an online database of comparative sequence and structure information for ribosomal, intron, and other RNAs. BMC Bioinformatics 3: 15.

Chandler DP, Brockman FJ, Bailey TJ, Fredrickson JK . (1998). Phylogenetic diversity of archaea and bacteria in a deep subsurface paleosol. Microb Ecol 36: 37–50.

Coolen MJL, Cypionka H, Sass AM, Sass H, Overmann J . (2002). Ongoing modification of Mediterranean sapropels mediated by prokaryotes. Science 296: 2407–2410.

D'Hondt S, Jørgensen BB, Miller DJ, Batzke A, Blake R, Cragg BA et al. (2004). Distributions of microbial activities in deep subseafloor sediments. Science 306: 2216–2221.

D'Hondt S, Rutherford S, Spivack AJ . (2002). Metabolic activity of subsurface life in deep-sea sediments. Science 295: 2067–2070.

DeLong EF . (1992). Archaea in coastal marine environments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 5685–5689.

DeLong EF . (1998). Everything in moderation: archaea as ‘non-extremophiles’. Curr Opin Genet Devel 8: 649–654.

DeLong EF, Wu KY, Prezelin BB, Jovine RVM . (1994). High abundance of archaea in Antarctic marine picoplankton. Nature 371: 695–697.

Eek KM, Sessions AL, Lies DP . (2007). Carbon-isotopic analysis of microbial cells sorted by flow cytometry. Geobiology 5: 85–95.

Francis CA, Roberts KJ, Beman JM, Santoro AE, Oakley BB . (2005). Ubiquity and diversity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea in water columns and sediments of the ocean. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 14683–14688.

Fuhrman JA, McCallum NN, Davis AA . (1992). Novel archaebacterial group from marine plankton. Nature 356: 148–149.

Fuhrman JA, Ouverney CC . (1998). Marine microbial diversity studied via 16S RNA sequences: cloning results from coastal waters and counting of native archaea with fluorescent single cell probes. Aquat Ecol 32: 3–15.

Hallam SJ, Konstantinidis KT, Putnam N, Schleper C, Watanabe Y, Sugahara J et al. (2006a). Genomic analysis of the uncultivated marine crenarchaeote Cenarchaeum symbiosum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 18296–18301.

Hallam SJ, Mincer TJ, Schleper C, Preston CM, Roberts K, Richardson PM et al. (2006b). Pathways of carbon assimilation and ammonia oxidation suggested by environmental genomic analyses of marine Crenarchaeota. PLOS Biology 4: 520–536.

Hinrichs KU, Hayes JM, Bach W, Spivack AJ, Hmelo LR, Holm NG et al. (2006). Biological formation of ethane and propane in the deep marine subsurface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 14684–14689.

Hohn MJ, Hedlund BP, Harald H . (2002). Detection of 16S rDNA sequences representing the novel phylum ‘Nanoarchaeota’: indication for a wide distribution in high temperature biotopes. Syst Appl Microbiol 25: 551–554.

House C, Cragg BA, Teske A . (2003). Drilling contamination tests on ODP Leg 201 using chemical and particulate tracers. Proc. ODP, Init. Repts., 201 [CD-ROM]. Available from: Ocean Drilling Program, Texas A&M University, College Station TX 77845-9547, USA.

Huber H, Hohn MJ, Rachel R, Fuchs T, Wimmer VC, Stetter KO . (2002). A new phylum of archaea represented by a nanosized hyperthermophilic symbiont. Nature 417: 63–67.

Hutchinson CA, Smith HO, Pfannkoch C, Venter JC . (2005). Cell-free cloning using φ 29 DNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 17332–17336.

Inagaki F, Nunoura T, Nakagawa S, Teske A, Lever MA, Lauer A et al. (2006). Biogeographical distribution and diversity of microbes in methane hydrate-bearing deep marine sediments on the Pacific ocean margin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 2815–2820.

Inagaki F, Suzuki M, Takai K, Oida H, Sakamoto T, Aoki K et al. (2003). Microbial communities associated with geological horizons in coastal subseafloor sediments from the Sea of Okhotsk. Appl Environ Microbiol 69: 7224–7235.

Ingalls AE, Shah SR, Hansman RL, Aluwihare LI, Santos GM, Druffel ERM et al. (2006). Quantifying archaeal community autotrophy in the mesopelagic ocean using natural radiocarbon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 6442–6447.

Ishii K, Fukui M . (2001). Optimization of annealing temperature to reduce bias caused by a primer mismatch in multitemplate PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol 67: 3753–3755.

Jørgensen BB . (1982). Mineralization of organic matter in the sea bed—the role of sulfate reduction. Nature 296: 643–645.

Jurgens G, Lindstrom K, Saano A . (1997). Novel group within the kingdom Crenarchaeota from boreal forest soil. Appl Environ Microbiol 63: 803–805.

Kalyuzhnaya MG, Zabinsky R, Bowerman S, Baker DR, Lidstrom ME, Chistoserdova L . (2006). Fluorescence in situ hybridization-flow cytometry-cell sorting-based method for separation and enrichment of type I and type II methanotroph populations. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 4293–4301.

Karner MB, DeLong EF, Karl DM . (2001). Archaeal dominance in the mesopelagic zone of the Pacific Ocean. Nature 409: 507–510.

Kim BS, Oh HM, Kang H, Chun J . (2005). Archaeal diversity in tidal flat sediment as revealed by 16S rDNA analysis. J Microbiol 43: 144–151.

Knittel K, Lösekann T, Boetius A, Kort R, Amann R . (2005). Diversity and distribution of methanotrophic archaea at cold seeps. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 467–479.

Könneke M, Bernhard AE, de la Torre JR, Walker CB, Waterbury JB, Stahl DA . (2005). Isolation of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing marine archaeon. Nature 437: 543–546.

Kormas KA, Smith DC, Edgcomb V, Teske A . (2003). Molecular analysis of deep subsurface microbial communities in Nankai Trough sediments (ODP Leg 190, Site 1176). FEMS Microb Ecol 45: 115–125.

Lever M, Teske A . (2007). Vertical distribution of methanogens and active archaea in subsurface sediments of the peru trench as evaluated from functional genes and 16S rRNA profiles. Abstract and Presentation at ASLO Ocean Sciences Meeting, Santa Fe, NM.

Lever MA, Alperin M, Inagaki F, Nakagawa S, Steinsbu BO, Teske A et al. (2006). Trends in basalt and sediment core contamination during IODP expedition 301. Geomicrobiol J 23: 517–530.

Lloyd KG, Lapham L, Teske A . (2006). An anaerobic methane-oxidizing community of ANME-1b archaea in hypersaline Gulf of Mexico sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 7218–7230.

Mauclaire L, Zepp K, Meister P, McKenzie J . (2004). Direct in situ detection of cells in deep-sea sediment cores from the Peru Margin (ODP leg 201, site 1229). Geobiology 2: 217–223.

Newberry CJ, Webster G, Weightman AJ, Fry JC . (2004). Diversity of prokaryotes and methanogenesis in deep subsurface sediments from the Nankai Trough, Ocean Drilling Program Leg 190. Environ Microbiol 6: 274–287.

Ouverney CC, Fuhrman JA . (2000). Marine planktonic archaea take up amino acids. Appl Environ Microbiol 66: 4829–4833.

Ovreas L, Forney L, Daae FL, Torsvik V . (1997). Distribution of bacterioplankton in meromictic Lake Saelenvannet, as determined by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of PCR-amplified gene fragments coding for 16S rRNA. Appl Environ Microbiol 63: 3367–3373.

Pace NR, Stahl DA, Lane DJ, Olsen GL . (1986). The analysis of natural microbial populations by ribosomal RNA sequences. Adv Microbiol Ecol 9: 1–55.

Parkes RJ, Cragg BA, Banning N, Brock F, Webster G, Fry JC et al. (2007). Biogeochemistry and biodiversity of methane cycling in subsurface marine sediments (Skagerrak, Denmark). Environ Microbiol 9: 1146–1161.

Parkes RJ, Cragg BA, Wellsbury P . (2000). Recent studies on bacterial populations and processes in subseafloor sediments: a review. Hydrogeology J 8: 11–28.

Parkes RJ, Webster G, Cragg BA, Weightman AJ, Newberry CJ, Ferdelman TG et al. (2005). Deep sub-seafloor prokaryotes stimulated at interfaces over geological time. Nature 436: 390–394.

Pearson A, McNichol AP, Benitez-Nelson BC, Hayes JM, Eglinton TI . (2001). Origins of lipid biomarkers in Santa Monica Basin surface sediment: a case study using compound-specific delta C-14 analysis. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 65: 3123–3137.

Podar M, Abulencia CB, Walcher M, Hutchison D, Zengler K, Garcia JA et al. (2007). Targeted access to the genomes of low-abundance organisms in complex microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 3205–3214.

Raghunathan A, Ferguson HR, Bornarth CJ, Song W, Driscoll M, Lasken RS . (2005). Genomic amplification from a single bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 3342–3347.

Raskin L, Stromley JM, Rittmann BE, Stahl DA . (1994). Group-specific 16S rRNA hybridization probes to describe natural communities of methanogens. Appl Environ Microbiol 60: 1232–1240.

Reed D, Fujita Y, Delwiche ME, Blackwelder DB, Sheridan PP, Uchida T et al. (2002). Microbial communities from methane hydrate-bearing deep marine sediments in a forearc basin. Appl Environ Microbiol 68: 3759–3770.

Reysenbach AL, Longnecker K, Kirshtein J . (2000). Novel bacterial and archaeal lineages from an in-situ growth chamber deployed at a mid-atlantic ridge hydrothermal vent. Appl Environ Microbiol 66: 3798–3806.

Schippers A, Neretin NL, Kallmeyer J, Ferdelman TG, Cragg BA, Parkes JR et al. (2005). Prokaryotic cells of the deep sub-seafloor biosphere identified as living bacteria. Nature 433: 861–864.

Smith DA, Spivack AJ, Fisk MR, Haveman SA, Staudigel H, ODP Leg 185 Shipboard Scientific Party. (2000). Tracer-based estimates of drilling-induced microbial contamination of deep sea crust. Geomicrobiology J 17: 207–219.

Sogin ML, Morrison HG, Huber JA, Welch DM, Huse SM, Neal PR et al. (2006). Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the under explored ‘rare biosphere’. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 12115–12120.

Sørensen KB, Lauer A, Teske A . (2004). Archaeal phylotypes in a metal-rich, low-activity deep subsurface sediment of the Peru Basin, ODP Leg 201, Site 1231. Geobiology 2: 151–161.

Sørensen KB, Teske A . (2006). Stratified communities of active archaea in deep marine subsurface sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 4596–4603.

Stahl DA, Amann RI . (1991). Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M (eds). Wiley: New York, NY.

Stein LY, Jones G, Alexander B, Elmund K, Wright-Jones C, Nealson KH . (2002). Intriguing microbial diversity associated with metal-rich particles from a freshwater reservoir. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 42: 431–440.

Sturt HF, Summons RE, Smith KJ, Elvert M, Hinrichs KU . (2004). Intact polar lipids in prokaryotes and sediments deciphered by high-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization multistage mass spectrometry—new biomarkers for biogeochemistry and microbial ecology. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 18: 617–628.

Takai K, Horikoshi K . (1999). Genetic diversity of archaea in deep-sea hydrothermal vent environments. Genetics 152: 1285–1297.

Takai K, Horikoshi K . (2000). Rapid detection and quantification of members of the archaeal community by quantitative PCR using fluorogenic probes. Appl Environ Microbiol 66: 5066–5072.

Takai K, Moser DP, DeFlaun M, Onstott TC, Fredrickson JK . (2001). Archaeal diversity in waters from deep South African gold mines. Appl Environ Microbiol 67: 5750–5760.

Takai K, Oida H, Suzuki Y, Hirayama H, Nakagawa S, Nunoura T et al. (2004). Spatial distribution of marine crenarchaeota group I in the vicinity of deep-sea hydrothermal systems. Appl Environ Microbiol 70: 2404–2413.

Teske A . (2006). Microbial communities of deep marine subsurface sediments: molecular and cultivation surveys. Geomicrobiol J 23: 357–368.

Teske A, Hinrichs KU, Edgcomb V, Gomez AdV, Kysela D, Sylva SP et al. (2002). Microbial diversity of hydrothermal sediments in the Guaymas Basin: evidence for anaerobic methanotrophic communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 68: 1994–2007.

Valentine DL . (2007). Adaptations to energy stress dictate the ecology and evolution of the archaea. Nat Rev Microbiol 5: 316–323.

Vetriani C, Jannasch HW, MacGregor BJ, Stahl DA, Reysenbach AL . (1999). Population structure and phylogenetic characterization of marine benthic archaea in deep-sea sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 65: 4375–4384.

Webster G, Parkes RJ, Cragg BA, Newberry CJ, Weightman AJ, Fry JC . (2006). Prokaryotic community composition and biogeochemical processes in depp subseafloor sediments from the Peru Margin. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 58: 65–85.

Whitman WB, Coleman DC, Wiebe WJ . (1998). Prokaryotes: the unseen majority. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 6578–6583.

Wilms R, Köpke B, Sass H, Chang TS, Cypionka H, Engelen B . (2006a). Deep biosphere-related bacteria within the subsurface of tidal flat sediments. Environ Microbiol 8: 709–719.

Wilms R, Sass H, Köpke B, Koster H, Cypionka H, Engelen B . (2006b). Specific bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic communities in tidal-flat sediments along a vertical profile of several meters. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 2756–2764.

Wuchter C, Schouten S, Boschker HTS, Damsté JS . (2003). Bicarbonate uptake by marine crenarchaeota. FEMS Microbiol Lett 219: 203–207.

Zhang K, Martiny AC, Reppas NB, Barry KW, Malek J, Chisholm S et al. (2006). Sequencing genomes from single cells by polymerase cloning. Nat Biotechnol 24: 680–686.

Zheng D, Alm EW, Stahl DA, Raskin L . (1996). Characterization of universal small-subunit rRNA hybridization probes for quantitative molecular microbial ecology studies. Appl Environ Microbiol 62: 4504–4513.

Acknowledgements

A Teske was supported by the NASA Astrobiology Institutes at MBL (Environmental Genomes, S/C NCC2-1054) and at URI (Subsurface Biospheres NCC2-1275), and by NSF (OCE-Ocean Drilling Program 0527167). K Sørensen was supported by the Marie Curie Transfer of Knowledge program (ABIOS). We thank JF Biddle for critical reading of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Teske, A., Sørensen, K. Uncultured archaea in deep marine subsurface sediments: have we caught them all?. ISME J 2, 3–18 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2007.90

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2007.90

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Microbial diversity in extreme environments

Nature Reviews Microbiology (2022)

-

Genomic evidence of functional diversity in DPANN archaea, from oxic species to anoxic vampiristic consortia

ISME Communications (2022)

-

Community structure and activity potentials of archaeal communities in hadal sediments of the Mariana and Mussau trenches

Marine Life Science & Technology (2022)

-

Identification of mutations in SARS-CoV-2 PCR primer regions

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Genomic evidence for sulfur intermediates as new biogeochemical hubs in a model aquatic microbial ecosystem

Microbiome (2021)