Abstract

Gingival fibromatosis is a rare disease, especially its syndromic form. Here, we review the literatures on gingival fibromatosis and briefly summarize some characters on clinical, etiological, genetic and histopathological aspects. We also present a rare case of gingival fibromatosis with multiple unusual findings in a 21-year-old man. And we differentiate it from some well-known syndromes including gingival fibromatosis. Maybe it implies a new syndrome within the spectrum of those including gingival fibromatosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gingival fibromatosis (GF) is a rare disease that is characterized by benign, slowly progressive, non-hemorrhagic, fibrous enlargement of maxillary and mandibular gingival.1,2,3 The prevalence is one per 175 000 population, and men and women are equally affected.4,5

Clinically, the onset is consistent with the eruption of permanent dentition. At times, it is correlated to the eruption of primary dentition. It rarely presents at birth.6 Overgrowth can be observed varying in extent and severity. The excess gingival tissue may cover partial or whole crown, resulting in diastemas, teeth displacement, retention of primary teeth, or impacted teeth. The hyperplastic gingiva is usually normal in color, with firm consistency and heavy stippling.1,6,7

To date, the precise pathogenesis is poorly known. Some researchers believe that the pathogenesis is confined to the fibroblasts in gingiva. A considerable number of articles support an increase of fibroblasts in GF.5 Decreased apoptosis together with increased proliferative activity in fibroblasts could contribute to fibrotic overgrowth of gingival.8 But it is still controversial if there is correlation between the amount of fibroblasts and that of collagen in all GF types, for some studies show relatively few fibroblasts.9 Impaired balance between production and degradation of collagen may also contribute to the disease.9,10 Research at molecular level reveals abnormal expression of some molecules related to extracellular matrix metabolism, such as transforming growth factor-β, and the abnormal expression at last leads to increased extracellular matrix deposition that contribute to pathogenesis.9

With the development of molecular genetics, some genes that responsible for GF have been mapped to some candidate intervals,9 including GINGF1 (2p21–p22) and GINGF3 (2p22.3–p23.3) on chromosome 2p, GINGF2 on chromosome 5q (5q13–q22), and GINGF4 (11p15) on chromosome 11p. Son of sevenless-1 mutation has been identified at the GINGF1 locus in a single autosomal dominant hereditary GF family, and son of sevenless-1 mutation is responsible for non-syndromic/isolated hereditary GF.3,4 There is still consensus regarding the specific genes responsible for syndromic GF.

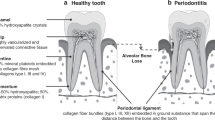

The histological findings of this entity are nonspecific. The overlying epithelium is hyperplasia and hyperkeratesis with elongated rete ridges extending deeply into the underlying fibrous connective tissue.1,2,4,11 Similar cases have been shown to demonstrate little or mild chronic inflammatory infiltration.5 Dense connective tissue is composed of densely arranged collagen-fiber bundles with scarce blood vessels and increased fibroblasts in most cases.1,2,4,11

Case report

A 21-year-old man, with complaint of gingival overgrowth in the past 15 years resulting in protruding lips, came to our Department of Stomatology. His mother told us that the patient suffered from hearing loss. She had seen the milk flowing out from his ear in his infancy. His visual acuity was quiet poor. He presented mental retardation, for his answers to our questions were vague and unclear. Medical history revealed no significant medication, no history of smoking or alcohol consumption. His parents were non-consanguineous adults. He had a younger brother. None of his relatives was involved of similar disease.

He presented striking facial appearance (Figure 1a). His cartilago nasi lateralis and greater alar cartilage were relatively soft. Multiple melanotic nevi distributed throughout the body, especially left aspect of head and neck. He had a height of 174 cm, weight of 73 kg and head circumference of 57 cm. These parameters were within normal limits. His intercanthal distance was 3.8 cm, wider than normal value. For differential diagnosis with Zimmerman–Laband syndrome, we also measured the length of his digits, and the results were normal. Hand and foot radiographs showed normal distal phalanges.

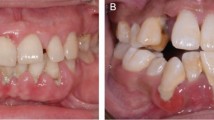

Apperance and intra-oral view. (a) Strange appearance: thick and sharply arched eyebrows, telecanthus, lapsus palpebrae superioris, saddle nose and brachyrhinia, and thick lips. (b) Gingival overgrowth with displacement of maxillary canine. The gingiva was pink, firm, nodular and non-hemorrhagic. (c) Maxillary gingival overgrowth with diastema in premolar region. All molars are impacted. (d) Gingival overgrowth of mandible, mainly in premolar region, is less severe than that of maxilla.

There was massive gingival overgrowth in both maxillary and mandibular arches (Figure 1b–1d). The enlarged gingiva was pink, firm and nodular. Bleeding on probing is negative. The overgrowth caused tooth displacement, tooth diastema and mastication problems.

Panoramic radiograph (Figure 2a) showed coarse trabecular pattern in alveolar bone. All molars were impacted in a thick layer of bone. There was a maxillary medial embedded supernumerary tooth. The maxillary lateral incisors were missing. There were multiple small radiopacities adjacent to the crowns of the unerupted molars on the mandible, suggesting an odontogenic tumor or benign fibro-osseous disease process. In order to investigate the nature of radiopacities, a computerized tomography (CT) scan (Figure 2b and 2c) was performed. It showed uneven enlarging and forward-protruding of maxillary alveolar bone. Our radiologist considered osteofibrosis of maxillary alveolar bone. There was no apparently abnormal morphous of mandible. There was no abnormal finding on lateral skull and chest radiograph.

The imaging pictures of patient. (a) Panoramic radiograph: all molars are embedded in a thick layer of bone. Some mandibular molars are near to the lower margin of mandible. There is a maxillary medial embedded supernumerary tooth. The maxillary lateral incisors are missed. (b) and (c) CT scan of maxilla and mandible: the maxillary alveolar bone is non-uniformly enlarged and forward-protruding, with coarse surface of cortical bone. There are multiple endogenic teeth in bilateral maxillary sinus. Multiple upper and lower teeth are not erupted. There is no obvious morphological abnormality of mandible. (d) and (e) MRI of skull: the signal of brain parenchyma is normal. The fourth ventricle is slightly enlarged. Subarachnoid space of bilateral frontal region and posterior cranial fossa is enlarged. Some cerebral sulci of cerebellum are slightly wider and deeper. The morphology and position of other ventricles and cerebral sulci are normal. The midline is also in its normal position. CT, computerized tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

We invited doctor of otolaryngology for consultation. The examinations showed normal external acoustic meatus and intact tympanic membrane. The doctor suggested a pure tone test and acoustic immittance measurement. The pure tone test showed decline of both air-conduction and bone-conduction curve, with some air-bone gap (>10 dB). The result referred to mixed deafness. The acoustic immittance measurement got an Ad-type curve referring to increased activity of middle ear. CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of cochlea was suggested for better understanding; however, the patient’s family refused. Considering mental retardation, we invited neurologist. The neurologist found no positive clinical signs, but suggested to perform MRI of skull and electroencephalogram. Electroencephalogram showed no apparent abnormality, while the result of MRI (Figure 2d and 2e) was remarkable. The fourth ventricle and the subarachnoid space of bilateral frontal region and posterior cranial fossa were enlarged. Anfractuosity of cerebellum was relatively wide and deep. These signs referred to atrophy or mild dysplasia of frontal lobe and cerebellum. With the patient’s consent, we invited our psychiatrist to do IQ assessment through Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Adut-Chinese Revised. And the patient got a score of 63 referring to mild mental retardation.

We also invited ophthalmologist. After examination, a diagnosis of congenital cataracta and concomitant esotropia (about 15°) was made. In order to better understand, we performed optometry, slit lamp examination and A-mode ultrasound. The patient suffered from high myopia (R: −19.00−1.50×40−0.12; L: −18.00−1.75×160−0.10). The ocular A-mode ultrasound showed the axial lengths of his right and left eyes were 32.55 and 32.45 mm respectively. These parameters were significantly higher than normal (about 24 mm). They were consistent with his high myopia. Slit lamp examination revealed typical opacities of congenital cataracts (Figure 3). Given the patient’s history (age, no history of ocular trauma, no history of diabetes), the diagnosis of congenital cataracts was made.

Laboratory examinations were performed, including bone mineral density, free thyroxine, thyroid stimulating hormone and sexual hormone. The results failed to reveal any significant findings. Ultrasonography revealed intrahepatic lipidoses and normal gallbladder, pancreas, spleen and bilateral kidney and adrenal glands. Karyotyping was also performed. We got 46 chromosomes with XY-sex chromosome. The number and structure were both normal.

After ruling out surgical contraindication, a biopsy was performed under local anesthesia. We cut a piece of gingival tissue with its underlying alveolar bone. The site was approximately 0.5 cm away from the distal surface of left maxillary canine. The histological features were consistent with GF (Figure 4).

Histopathology of specimen: accumulation of excessive mature collagen fibers, in thick bundles, among which distributing multiple fibrocytes, with fibroblasts occasionally seen. The overlying epithelium is hyperplastic with elongated rete ridges interwoven into a network. Mature cortical bone is also observed with clear lacunae and osteocytes. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, ×100.

Based on the clinical and histological findings, a diagnosis of syndromic GF was made. Initial management consisted of scaling/root planing and oral hygiene encouragement. Later, we planned to perform ectomy of excessive alveolar bone and gingiva under general anesthesia. Being informed the risk and recurrence, the patient and his family refused surgery. So we suggested close follow-up. So far, the patient is in stable condition.

Discussion

GF can be an isolated entity, or as part of a syndrome or chromosomal abnormality.2,6 Some syndromic GF should be taken into consideration for differential diagnosis are listed in Table 1.9

It is similar to Jones Syndrome, a dominantly inherited disease first described in 1977.12 But the present case is substantially different from Jones syndrome, for his neural hearing loss is stable, not progressive. What’s more, the patient suffers from conductive deafness. However, we suppose that conductive deafness may be the sequela of acute suppurative otitis media, for the pus of suppurative otitis media can be easily mistaken with milk his mother saw. In this sense, there is consensus whether his conductive deafness is congenital or not. Since the patient refused CT and MRI of cochlea, we cannot give a definite conclusion.

Our patient has embedded supernumerary teeth, more like Wynne’s case. Wynne et al.13 in 1995 reported three generations in a family with GF associated with hearing loss, hypertelorism and supernumerary teeth. They proposed that it represented a new syndrome despite its similarity to Jones syndrome. Besides Jones syndrome, supernumerary teeth have also been observed in Zimmermann–Laband syndromes.14

Oligodontia of the maxillary lateral incisors is common in normal population, so its significance here is not clear. A more striking and important dental feature is the failure of eruption of all permanent molars. All molars are bone impaction. It is easy to understand the maxillary molars impaction for abnormal osteofibrosis of alveolar bone. But why all the mandible molars impacted? There is no osteofibrosis of mandible. Maybe it implies abnormal development of dental germ for some molars are near to lower margin of mandible. Although several investigators believe that the presence of teeth is a precondition for GF to occur, there is still obvious gingival overgrowth at molar regions in our case.

Zimmerman–Laband syndrome should also be strongly considered because of the association with multiple unerupted teeth; however, the characteristic nose and bone defects, digital anomalies, epilepsy and hepatosplenomegaly are absent.

It is believed that the alveolar bone is always not affected.9 However, the patient displays osteofibrosis of maxillary alveolar bone. Someone may disagree with the view that the enlargement of the alveolar ridges is primarily due to fibromatosis rather than osteofibrosis. The gingival enlargement of upper alveolar ridges is indeed due to both fibromatosis and osteofibrosis. But there is also gingival enlargement in lower alveolar ridges, while mandible is of normal morphology. So we had better to say that both fibromatosis and osteofibrosis contribute to gingival enlargement. And it dose not conflict with the diagnosis of GF.

The patient suffers from congenital cataracta and concomitant esotropia. Both symptoms are rare observed in syndromic GF. Previously observed ocular symptoms in syndromic GF include atypical retinitis pigmentosa15 and developmental cataracta16 in Zimmermann–Laband syndromes, corneal dystrophy in Rutherfurd syndrome,9 nanophthalmos and microcornea in Cross syndrome.9 To our knowledge, Shah’s case is the only case suffered from cataracta.16 What’s more, concomitant esotropia has not been reported in syndromic GF to date. Concomitant esotropia may be the result of abnormal function of frontal lobe or mechanical factors. Since the patient refused MRI of eyes, we cannot give a definite conclusion. The patient’s lengthened ocular axis may be due to two reasons: congenital abnormalities in development; or secondary to congenital cataracts for congenital cataracts would cause form deprivation myopia.

Clinically, the patient appears no defective coordination, contradicting with the result of MRI. So we suppose the possibility of congenital brain defects, for congenital defects can be compensated. His low IQ score may be the result of congenital brain defects. So mild mental retardation may not be an independent symptom.

As is known, the onset age of GF is around 6. From his pedigree of three generations, all of his relatives have passed the onset age, but none is involved. For lack of a positive family history, we cannot determine a possible mode of inheritance. However, we can rule out chromosomal abnormality. Our geneticist suggested genetic testing, but the patient’s family refused. According to the summary of Hakkinen and Csiszar,9 most cases of GF, no matter isolated cases or associated with syndromes, are autosomal dominant. Only cherubism syndrome is autosomal recessive, while hypertrichosis syndrome is X-linked autosomal recessive/dominant. So we think that our case is likely to be a sporadic autosomal dominant case, resulting from some mutation.

Conclusions

The present case is complex for multiple previously unreported manifestations. Maybe it implies a new syndrome characterized by GF, osteofibrosis of maxillary alveolar bone, congenital cataracta and concomitant esotropia, multiple unerupted teeth, cerebral and cerebellar anomalies, mild mental retardation, mixed hearing loss and facial dysmorphism.

References

Bayar GR, Ozkan A, Sencimen M et al. Idiopathic gingival fibromatosis: a case report. Gülhane Tip Derg 2011; 53( 4): 294–296.

Chaturvedi R . Idiopathic gingival fibromatosis associated with generalized aggressive periodontitis: a case report. J Can Dent Assoc 2009; 75( 4): 291–295.

Hart TC, Zhang Y, Gorry MC et al. A mutation in the SOS1 gene causes hereditary gingival fibromatosis type 1. Am J Hum Genet 2002; 70( 4): 943–954.

Kather J, Salgado MA, Salgado UF et al. Clinical and histomorphometric characteristics of three different families with hereditary gingival fibromatosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008; 105( 3): 348–352.

Kavvadia K, Pepelassi E, Alexandridis C et al. Gingival fibromatosis and significant tooth eruption delay in an 11-year-old male: a 30-month follow-up. Int J Paediatr Dent 2005; 15( 4): 294–302.

Breen GH, Addante R, Black CC . Early onset of hereditary gingival fibromatosis in a 28-month-old. Pediatr Dent 2009; 31( 4): 286–288.

Baptista IP . Hereditary gingival fibromatosis: a case report. J Clin Periodontol 2002; 29( 9): 871–874.

Kantarci A, Augustin P, Firatli E et al. Apoptosis in gingival overgrowth tissues. J Dent Res 2007; 86( 9): 888–892.

Hakkinen L, Csiszar A . Hereditary gingival fibromatosis: characteristics and novel putative pathogenic mechanisms. J Dent Res 2007; 86( 1): 25–34.

Gagliano N, Moscheni C, Dellavia C et al. Morphological and molecular analysis of idiopathic gingival fibromatosis: a case report. J Clin Periodontol 2005; 32( 10): 1116–1121.

Doufexi A, Mina M, Ioannidou E . Gingival overgrowth in children: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and complications. A literature review. J Periodontol 2005; 76( 1): 3–10.

Jones G, Wilroy RS Jr, McHaney V . Familial gingival fibromatosis associated with progressive deafness in five generations of a family. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser 1977; 13( 3B): 195–201.

Wynne SE, Aldred MJ, Bartold PM . Hereditary gingival fibromatosis associated with hearing loss and supernumerary teeth—a new syndrome. J Periodontol 1995; 66( 1): 75–79.

Holzhausen M, Goncalves D, Correa Fde O et al. A case of Zimmermann–Laband syndrome with supernumerary teeth. J Periodontol 2003; 74( 8): 1225–1230.

Koch P, Wettstein A, Knauber J et al. A new case of Zimmermann–Laband syndrome with atypical retinitis pigmentosa. Acta Derm Venereol 1992; 72( 5): 376–379.

Shah N, Gupta YK, Ghose S . Zimmermann–Laband syndrome with bilateral developmental cataract—a new association? Int J Paediatr Dent 2004; 14( 1): 78–85.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Fengguo Yan, Dr Pengfang Lin and Professor Xingchao Shentu for their patient and responsible consultations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

He, L., Ping, FY. Gingival fibromatosis with multiple unusual findings: report of a rare case. Int J Oral Sci 4, 221–225 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijos.2012.53

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijos.2012.53