Abstract

Background:

Liraglutide 3.0 mg, with diet and exercise, produced substantial weight loss over 1 year that was sustained over 2 years in obese non-diabetic adults. Nausea was the most frequent side effect.

Objective:

To evaluate routinely collected data on nausea and vomiting among individuals on liraglutide and their influence on tolerability and body weight.

Design:

A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind 20-week study with an 84-week extension (sponsor unblinded at 20 weeks, open-label after 1 year) in eight European countries (Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00422058).

Subjects:

After commencing a 500-kcal/day deficit diet plus exercise, 564 participants (18–65 years, body mass index (BMI) 30–40 kg m−2) were randomly assigned (after a 2-week run-in period) to once-daily subcutaneous liraglutide (1.2, 1.8, 2.4 or 3.0 mg), placebo or open-label orlistat (120 mg × 3 per day). After 1 year, participants on liraglutide/placebo switched to liraglutide 2.4 mg, and subsequently, to liraglutide 3.0 mg (based on 20-week and 1-year results, respectively).

Results:

The intention-to-treat population comprised 561 participants (n=90–98 per arm, age 45.9±10.3 years, BMI 34.8±2.7 kg m−2 (mean±s.d.)). In year 1, more participants reported ⩾1 episode of nausea/vomiting on treatment with liraglutide 1.2–3.0 mg (17–38%) than with placebo or orlistat (both 4%, P⩽0.001). Most episodes occurred during dose escalation (weeks 1–6), with ‘mild’ or ‘moderate’ symptoms. Among participants on liraglutide 3.0 mg, 48% reported some nausea and 13% some vomiting, with considerable variation between countries, but only 4 out of 93 (4%) reported withdrawals. The mean 1-year weight loss on treatment with liraglutide 3.0 mg from randomization was 9.2 kg for participants reporting nausea/vomiting episodes, versus 6.3 kg for those with none (a treatment difference of 2.9 kg (95% confidence interval 0.5–5.3); P=0.02). Both weight losses were significantly greater than the respective weight losses for participants on placebo (P<0.001) or orlistat (P<0.05). Quality-of-life scores at 20 weeks improved similarly with or without nausea/vomiting on treatment with liraglutide 3.0 mg.

Conclusion:

Transient nausea and vomiting on treatment with liraglutide 3.0 mg was associated with greater weight loss, although symptoms appeared tolerable and did not attenuate quality-of-life improvements. Improved data collection methods on nausea are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is described by the WHO (World Health Organization) as one of the most important public health threats.1, 2 It is a major factor in the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, certain cancers, sleep apnea, osteoarthritis and depression.3 Obese individuals often have lower self-esteem and a poorer quality of life (QoL) than do normal-weight individuals.4, 5 Within routine primary care, diet and exercise-based intervention can be cost-effective, but only a small minority6 achieve the >5% weight loss at 12 and 24 months that is associated with improvements in obesity-related cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 A largely unmet medical need for adjunctive and effective anti-obesity pharmacotherapy exists.12 The safety and side-effect profiles of pharmaceutical agents are in particular focus because obesity is usually a chronic condition demanding long-term treatment.13, 14

Liraglutide is an analog of the incretin and satiety hormone, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), which decreases energy intake and promotes weight loss and glucose-stimulated insulin release.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 Subcutaneous liraglutide (Victoza, Novo Nordisk A/S, Bagsvaerd, Denmark), at once-daily doses of up to 1.8 mg per day, is approved in the EU and US for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus,23, 24 and liraglutide 3.0 mg per day is currently under investigation for weight management. A phase 2 randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 564 obese non-diabetic adults showed that liraglutide was more effective than orlistat or diet and exercise alone at reducing weight (the primary endpoint).25, 26 From randomization, participants on liraglutide 3.0 mg lost 7.2 kg of mean body weight at 20 weeks and 7.8 kg at 1 year (analysis of covariance). After 2 years, participants who had been randomized to liraglutide 2.4 or 3.0 mg (pooled group) sustained a mean weight loss of 5.3 kg. Those completing the full 2-year treatment period lost 7.8 kg from the time of commencing weight loss at run-in. The most frequently reported side effect with liraglutide was nausea, known to be induced by supraphysiological levels of native GLP-1 and by GLP-1 receptor agonists.14, 18, 27, 28 In phase 3 trials of liraglutide for type 2 diabetes mellitus, nausea was reported by up to 40% of individuals on liraglutide 1.2 or 1.8 mg per day, but was mostly mild and transient.29 Similarly, in this trial involving obese individuals, nausea was also the most frequently reported side effect, occurring mostly early in the trial during dose escalation.25 Vomiting, reported less frequently, also had a higher incidence among individuals on liraglutide treatment.

The aim of the current paper was to document more closely the data on nausea and vomiting from the phase 2 trial of liraglutide at doses of up to 3.0 mg per day in non-diabetic obese adults25, 26 in terms of incidence and tolerability and the relationship to weight loss.

Participants and methods

Full details of the study design and participants recruited have been published.25, 26 Local ethics committees approved the trial protocol, and the trial was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki30 and guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. The trial is registered with Clinicaltrials.gov, number NCT00422058.

Participants

Obese men and women gave informed written consent to participate in the trial, which was conducted at 19 clinical research centers in eight countries across Europe from January 2007 to April 2009. Eligible participants were aged 18–65 years and were of stable weight, with body mass index (BMI) of 30–40 kg m−2 and fasting plasma glucose of <7 mmol l−1 (126 mg dl−1) at the start of the run-in period. Individuals were excluded if they had been diagnosed with type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus or major medical conditions, had used approved weight-loss drugs within the previous 3 months, had received drug treatment known to induce weight gain or had received surgical obesity treatment.

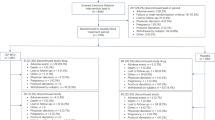

Study design

The study design is shown in Figure 1. Participants commenced weight loss with a 2-week ‘run-in’ period (diet, exercise and placebo injections), starting one week after screening. They were then randomized to treatment for 20 weeks, and most consented to enroll in the extension, continuing blinded on randomized treatment for a further 32 weeks (52 weeks in total). At week 20, the sponsor was unblinded to liraglutide/placebo treatment, whereas the participants and investigators remained blinded up to 1 year. After 1 year, when the 20-week data had been analyzed, the trial was fully unblinded. At 1 year, participants on liraglutide and placebo treatment switched to open-label treatment with liraglutide 2.4 mg, deemed the optimal dose from analysis of the 20-week data, undergoing dose escalation as necessary. However, after analysis of the 1-year efficacy and safety data, the 3.0-mg dose was, instead, considered optimal. Participants on liraglutide 2.4 mg therefore switched to liraglutide 3.0 mg in weeks 70–96 (timing was variable, occurring as sites obtained ethics-committee approval). Individuals on orlistat remained on a standard 3 × 120-mg dose for the full 2-year period. For the current paper, weight changes from randomization are given. It is of note that there was an additional mean weight loss of 1.3±1.4 kg during the run-in period prior to randomization.25

Treatment

After the run-in period, individuals were randomly assigned to double-blinded treatment (liraglutide, placebo or orlistat). Liraglutide doses of 1.2, 1.8, 2.4 or 3.0 mg were administered once daily by evening subcutaneous injection using a pre-filled injection pen (FlexPen, Novo Nordisk A/S, Bagsvaerd, Denmark) with NovoFine Needles 8 mm × 30 G (Novo Nordisk A/S), starting with doses of 0.6 mg per day and increasing by weekly increments of 0.6 mg (dose escalation). The open-label comparator group was randomized to receive orlistat capsules (3 × 120 mg per day) (Xenical, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) with each main meal for the full 2-year period.

During the run-in period and throughout treatment, all participants received dietary counseling for a nutritionally balanced low-calorie diet (with about 30% of total caloric intake from fat, 20% from protein and 50% from carbohydrates), providing an energy deficit of approximately 500 kcal per day below the estimated 24-h energy requirements31 (calculated as basal metabolic rate × physical activity level 1.3). Participants were also advised to maintain or increase physical activity.

Study measures

For regulatory purposes, side effects were recorded as adverse events and as responses to open questions at every visit or telephone contact from screening and up to 1 week after the last day on treatment. All adverse events (serious and non-serious) were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 10.1. Information about nausea or vomiting was thus collected as part of a routine adverse event collection. Participants had been made aware in the baseline subject information/informed consent material of the main side effects of liraglutide (‘diarrhea, nausea and in rare cases vomiting, and also headache and dizziness’). All events observed by the investigator or reported by participants either spontaneously or in response to open questions were recorded by the investigator on an adverse event form; these data were used as the basis for measuring the incidence of nausea and vomiting. The following information was recorded on the form: adverse-event diagnosis (if known, otherwise symptoms were listed), whether the event was serious or of special interest (requiring completion of a separate form), the date of onset, severity (mild, moderate or severe), outcome (recovered, recovering, recovered with sequelae, not recovered, fatal or unknown), causality in relation to the trial product (in the investigator’s opinion) and whether any action regarding trial products was taken. A ‘mild’ event was characterized by ‘no or transient symptoms, no interference with the subject’s daily activities’; a ‘moderate’ event was characterized by ‘marked symptoms, moderate interference with the subject’s daily activities’; and a ‘severe’ event was characterized by ‘considerable interference with the subject’s daily activities, unacceptable’.

According to the protocol, trial drug dose reduction or increase was not allowed, and participants were to be withdrawn if they could not tolerate treatment. However, intermittent pauses and slower dose escalation were permitted on a case-by-case basis, after discussion with the sponsor.

A ‘serious’ adverse event was one that resulted in at least one of the following outcomes: death, life-threatening experience, in-patient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, persistent or significant disability, a congenital anomaly/birth defect or any event that, based on appropriate medical judgment, jeopardizes the individual and may require medical or surgical intervention to prevent one of the described outcomes.

Health-related QoL was assessed using the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life—Lite (IWQoL-Lite) questionnaire.32 IWQoL-Lite is a validated, 31-item, self-reported measure of weight-related QoL that assesses physical function, self-esteem, sexual life, public distress and work. Finally, body weight was measured at every visit, starting from the screening visit, using calibrated scales.

Statistical analysis

The sample size estimation for the 20-week trial has been reported previously.25, 26 The effect of at least one episode of nausea/vomiting on weight change was investigated by analysis of covariance, and the effect of gender on the reporting of episodes of nausea/vomiting, as well as the incidence of these, was tested using logistic regression. These were post-hoc analyses performed on a modified intention-to-treat population (comprising randomized individuals having at least one treatment dose and at least one post-randomization assessment) using last-observation-carried-forward. Analyses at year 1 tested the superiority of each liraglutide dose over placebo and orlistat. At year 2, the superiority of liraglutide (pooled group of participants on 2.4/3.0 mg over 2 years) over orlistat was assessed. IWQoL-Lite scores were transformed using scoring methods provided in the IWQoL-Lite scoring manual, with a score range of 0–100. Differences in QoL of individuals experiencing some nausea/vomiting versus those who did not were assessed using analysis of covariance post-hoc. For analysis of covariance, treatment, country and sex were fixed effects, and randomization value was a covariate, with multiplicity adjustment being made using Dunnett's method. The same model parameters were used for the regression analyses, using Bonferroni correction for multiplicity adjustment. All analyses were two-sided, with 5% significance, and were performed using the Statistical Analysis System software package (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Trial population

Of 616 individuals entering the 2-week run-in period, 52 (8%) withdrew, leaving 564 to receive randomized treatment: 135 men (24%) and 429 women (76%). 472 completed the 20-week trial and 398 chose to enroll in the extension period (74 discontinued), with 268 completing the full 2-year period (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 1). Of the 93 participants randomized to liraglutide 3.0 mg, 82 (88%) completed 20 weeks and 65 remained on liraglutide 3.0 mg at 1 year (30% withdrawals, including 10 who elected not to enroll in the extension at 20 weeks). At 2 years, 47 of the participants randomized to liraglutide 3.0 mg were still taking this dose (2-year withdrawal rate=49%).

Three individuals randomized to liraglutide were excluded from the intention-to-treat population owing to missing post-randomization weight data. Major protocol deviations during the trial have been described previously.25, 26

Participant characteristics were comparable across groups at randomization (Table 1) and on entering the extension (not shown). The mean age was 45.9±10.3 (s.d.) years, and BMI was 34.8±2.7 kg m−2.

Incidence of nausea and vomiting during year 1

The frequency of nausea and/or vomiting for women (n=135; 19% (95% confidence interval (CI) 13–26%)) was not statistically significantly different from that of men (n=29; 12% (95% CI 7–20%)): the odds ratio (female: male) was 1.7 (95% CI: 0.9–3.1; P=0.09). The proportion of individuals reporting nausea/vomiting at any time during year 1 on liraglutide was dose-dependent (Figure 2a), and statistically significantly greater than with placebo and orlistat for all liraglutide doses.

(a) The proportion of individuals reporting nausea/vomiting at any time during year 1 (logistic regression analysis). Data are estimated means. Odds ratios (OR) versus placebo/orlistat are shown, together with 95% CI. The proportion of participants reporting nausea (b) and vomiting (c) by country in year 1. (d) Severity of nausea and vomiting episodes reported in year 1. (e) The proportion of individuals with nausea at any time during 2 years of treatment, by week. Safety analysis set.

Reporting of nausea and vomiting by country

Reported incidence of nausea and vomiting varied widely between the eight recruiting countries (Figures 2b and c). The proportion of individuals on liraglutide (all doses) who reported nausea ranged from 0/47 (0%) (Czech Republic) to 27/75 (36%) (UK), and the proportion on liraglutide who reported vomiting ranged from 0/11 (0%) (Belgium) to 13/75 (17%) (UK).

Timing

Most episodes of nausea (42/68 (62%)) among individuals on liraglutide 3.0 mg were first reported in weeks 1–4, during dose escalation (Table 2). A total of 7 out of 16 (44%) vomiting bouts were reported in weeks 1–4, and 11 out of 16 (67%) were reported in weeks 1–6 among individuals on liraglutide 3.0 mg. No participant in any group reported ⩾4 nausea episodes. Episodes of nausea reported by individuals on liraglutide 3.0 mg after week 8 were mainly reported by those who had already experienced earlier episodes (15/18 (83%)). Most nausea and vomiting episodes were transient (data not shown). Data collected for regulatory purposes did not allow an exact assessment of the duration of reported symptoms or the frequencies of transient symptoms occurring between visits and assessments.

Withdrawals and temporary dose reduction

Most liraglutide 3.0 mg recipients who experienced nausea (36/45 participants (80%)) or vomiting (9/12 (75%)) reported only one episode, and only 4 out of 93 (4%) withdrew because of nausea/vomiting (one withdrew because of nausea; one withdrew because of vomiting; one withdrew because of nausea and vomiting; and one withdrew because of vomiting and diarrhea). In addition to withdrawals owing to nausea and vomiting (Table 2), one participant on liraglutide 1.8 mg and 2 on 2.4 mg withdrew for ‘other’ reasons (specifically, intolerance to the allocated dose) after 102, 64 and 65 days, respectively. No nausea episodes in the first year were rated ‘serious’ or led to temporary dose reduction or drug withdrawal.

Severity

Most reported episodes of nausea and vomiting were of ‘mild’ or ‘moderate’ intensity (Figure 2d). Among individuals on liraglutide, 73% of reported episodes of nausea were ‘mild’, 25% were ‘moderate’, and only 2% were ‘severe’. For vomiting, 46% of episodes were ‘mild’, 46% ‘moderate’, and 9% ‘severe’. Sixteen episodes of nausea among individuals on liraglutide were noted as ‘intermittent nausea’ by the participant/investigator, compared with two in the placebo group and one in the orlistat group; and six cases of ‘intermittent vomiting’ were reported among individuals on liraglutide.

Two episodes of vomiting were rated as ‘serious’ (Table 2). One serious episode started after 135 days on liraglutide 2.4 mg, and recovery was registered after 2 days, occurring at the same time as events of epigastric abdominal pain, nausea, headache and loss of vision in the left eye. This woman recovered from the events with no dose reduction, but withdrew consent to continue in the trial in year 2. She had other gastrointestinal disturbances during the trial (including diarrhea, retching and constipation as well as the above). The other serious vomiting episode had its onset after 266 days of treatment with liraglutide 3.0 mg, occurring simultaneously with an event of abdominal pain. Liraglutide was temporarily withdrawn; the woman recovered after 8 days and eventually completed the trial. She also had other gastrointestinal disorders (including nausea and constipation) as well as cholelithiasis (gallstones). Weight loss data for the two individuals who experienced the above events were not available.

Three non-serious vomiting episodes led to temporary dose reduction or drug withdrawal. Liraglutide dose was reduced after 22 days (during escalation to 2.4 mg) for one individual, who subsequently withdrew because of nausea on day 33. Another individual in the liraglutide 2.4 mg group had a temporary dose reduction after 2 days on account of vomiting, but recovered after 1 day and completed the trial. One in the orlistat group had treatment temporarily withdrawn because of vomiting after 123 days (but recovered after 3 days and completed the trial).

Incidence of nausea and vomiting during year 2

The proportion of individuals experiencing nausea at any time during 2 years of treatment is shown in Figure 2e. Just as the incidence of nausea was highest during dose escalation at the start of the trial, nausea was again observed at the start of the second year in individuals in the placebo and liraglutide 1.2 and 1.8 mg groups, when they switched to liraglutide 2.4 mg. During the 4-week dose-escalation period starting year 2, 23 individuals (34%) who were previously on placebo experienced some nausea, which was similar to the proportion undergoing dose escalation to 2.4 mg in the first year (32%). Only 3 of those 23 participants had experienced nausea in year 1 while on placebo. Fewer individuals who were already on liraglutide 1.2 and 1.8 mg reported nausea during dose escalation to 2.4 mg: 16 and 6.8%, respectively. Only one individual in each group already treated with liraglutide 2.4 and 3.0 mg experienced nausea in the first 4 weeks of year 2. No participant experienced vomiting in the group randomized to placebo during dose escalation to 2.4 mg, whereas 11 (12%) randomized to 2.4 mg had reported vomiting in the first 4 weeks of the trial.

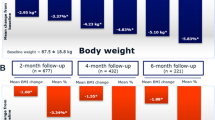

Association between nausea/vomiting and weight loss

After 1 year of treatment, the estimated mean weight loss from randomization with liraglutide 3.0 mg was 9.2 kg for those who experienced at least one episode of nausea/vomiting (n=49) and 6.3 kg for those who did not (n=43) (a treatment difference of 2.9 kg (95% CI 0.5–5.3); P=0.02) (Figure 3a). With liraglutide 3.0 mg, weight loss in individuals who reported no nausea/vomiting was still significantly greater than in those on both placebo (a treatment difference of 4.2 kg (2.1–6.4); P=0.0001) and orlistat (a treatment difference of 2.3 kg (0.14–4.4); P=0.04). The mean 1-year weight loss in individuals on liraglutide 3.0 mg who did experience episodes of nausea/vomiting was 7.8 kg (3.4–12.2) greater than in those on placebo (P=0.0006) and 6.6 kg (2.1–11.0) greater than in those on orlistat (P=0.004).

Weight change at year 1 (a) and year 2 (b) in individuals with or without at least one episode of nausea or vomiting. Mean changes (analysis of covariance) are shown for the intention-to-treat population with the last observation carried forward. Estimated treatment differences (ETD) are shown, together with 95% CI.

The estimated mean weight loss from randomization to year 2 for participants on liraglutide 2.4/3.0 mg (pooled group) was also significantly greater for those who experienced at least one episode of nausea/vomiting (6.9 kg, n=93) compared with those who did not (4.1 kg, n=91) (a treatment difference of 2.9 kg (0.8–4.9); P=0.006) (Figure 3b).

Association between nausea/vomiting and QoL

QoL scores at 20 weeks improved from randomization among individuals on liraglutide 3.0 mg, and mean scores for physical function, self-esteem and work were significantly greater than for those on placebo, as previously reported.25 No statistically significant differences were observed between individuals on liraglutide 3.0 mg who reported at least one episode of nausea/vomiting over 20 weeks and those who did not (Figure 4).

Mean (analysis of covariance) changes (positive=improved) in quality-of-life scores (IWQoL-Lite) among individuals on liraglutide 3.0 mg at 20 weeks, in individuals with or without at least one episode of nausea or vomiting (intention-to-treat population with the last observation carried forward). IWQoL-Lite scores ranged from 0 (worst) to 100 (best).

Discussion

We investigated the effects of liraglutide (at doses of up to 3.0 mg per day) on the incidence and tolerability of nausea and vomiting, as well as on weight loss, in obese non-diabetic individuals. Although these events were reported more often with liraglutide than with either placebo or orlistat, symptoms were mostly mild or moderate, transient and remarkably well tolerated. Nausea and vomiting were associated with up to 2.9 kg more weight loss after 1 year of treatment, which suggests an association with at least part of the mechanism of action of liraglutide-induced weight loss. However, QoL assessed at 20 weeks was not impaired, even at the highest 3.0-mg dose, which induced nausea in almost 50% of individuals, mainly in weeks 1–4 during dose escalation. The incidence of vomiting was lower, about a quarter of that of nausea, for individuals on liraglutide 3.0 mg, again mainly in the first 6 weeks. The incidence of nausea and vomiting was comparable for males and females. No nausea episodes were reported and only two vomiting episodes (reported in year 1, together with symptoms suggesting recurrent illness rather than a drug effect), were considered serious. Withdrawal from the study on account of nausea or vomiting was uncommon.

These data originate from a clinical trial whose primary aim was to investigate weight changes. Although information about nausea and vomiting was not collected using a specific questionnaire, it was possible to gain a reasonably clear understanding about such events from the data routinely reported on adverse events. The nature of this process, as well as possible differences in the way investigators inquired about and reported adverse events in the different centers and countries, may have affected the recording of these events. For instance, the incidence of reported nausea and vomiting in the eight recruiting countries varied substantially. The lack of systematic data collection on nausea and vomiting, and duration of episodes, is a limitation of this study, but is also an important lesson for future clinical trials. Variability in the assessment of adverse events in clinical trials has been previously reported.33, 34 Considerable differences in the categorization of adverse events were observed in an exercise following training of investigators on data collection.34 In another study of geographical variation in adverse-event reporting in 127 clinical trials of gastrointestinal indications, there were differences in the reporting rates of general and serious adverse events across the 13 countries involved.33 Notably in the current trial, nobody from the Czech Republic reported nausea, nor did anyone from Belgium report vomiting. Perhaps trial participants and investigators tend to emphasize different kinds of adverse events in different countries.33 It is also possible that the term into which ‘nausea’ is translated has a subtly different meaning in other languages, or can carry different cultural values, which may influence spontaneous reporting. In English, for example, the adjectives ‘nauseous’ or ‘nauseating’ may be used to indicate something unpleasant or boring, and the word ‘nausea’ itself is seldom used by non-health professionals.

In order to evaluate nausea and vomiting events more accurately, use of a rating scale similar to the Gastrointestinal System Rating Scale could be considered in future studies of drugs such as liraglutide. In the current trial, in common with most pharmaceutical trials, episodes of nausea and vomiting were only reported in terms of the onset date and then the date of ‘outcome’ (if recorded, usually the date of the next trial visit). Duration of single events, short episodes or ‘intermittent nausea’ could not be accounted for. Before enrollment, trial participants were informed about diarrhea, nausea and (rarely) vomiting as potential side effects associated with liraglutide. This could have led to over-reporting of these symptoms. Standardized, reliable ways to collect information on transient or intermittent adverse events, including precise duration periods, are needed.

Liraglutide appears to modulate its effects on body weight in the same way as native GLP-1,14, 15, 17, 35, 36 that is, through concomitant inhibition of appetite and energy intake37, 38 via activation of both peripheral and central GLP-1 receptors, although the exact mechanism is not known. The contribution of nausea to reductions in appetite and energy intake is less clear. In a study investigating the effect of gut hormones and appetite perceptions on energy intake in men, nausea was identified as an independent predictor of energy intake, although its effect size, as a contribution to energy-intake suppression, was small.39 Nausea occurs at the time of peak plasma liraglutide concentrations,40, 41 and weekly dose escalation can help to mitigate its incidence and severity.42 Nausea could be an effect of liraglutide on brain-stem areas involved in the regulation of appetite and fluid homeostasis that are unprotected by the blood–brain barrier, as it has also been reported by fasting individuals given GLP-1 or its derivatives.40, 43 Delayed gastric emptying has been associated with nausea, and both could contribute to weight loss with GLP-1 receptor agonists. However, inhibition of gastric emptying diminished within 14 days with liraglutide but not with exenatide treatment, whereas similar weight loss occurred in both groups.44 A recent study with liraglutide in rats suggests that delayed gastric emptying is transient, and the main mechanism for liraglutide-induced weight loss is mediated by stimulation of appetite neurons in the brain.45

Weight loss in the current trial was significantly greater for individuals on liraglutide 3.0 mg than for those on placebo (or orlistat) after 1 year, and those on liraglutide 3.0 mg who did not report any nausea or vomiting also lost significantly more weight than those on placebo or orlistat. Thus, reported nausea contributes to weight loss but is not the main mechanism behind liraglutide-induced weight loss. Additional factors associated with obesity that may compound the action of liraglutide to contribute to a higher incidence of nausea and vomiting are a larger residual gastric volume, increased esophageal reflux and increased gallbladder and gastrointestinal disease.46

In the current study, reported nausea was intriguingly tolerable for most affected individuals. Nausea and vomiting led to few withdrawals in the first year of treatment, and only two cases (both vomiting) were rated as ‘serious’, both with features to suggest intercurrent illness. Certain individuals may be more susceptible to nausea, but our analysis did not specifically examine predictors. Importantly, however, QoL was not impaired in those who reported nausea/vomiting, improving to the same extent at 20 weeks as for those who did not.

In summary, liraglutide is associated with dose-dependent nausea, and almost half the individuals on liraglutide 3.0 mg reported nausea at some time over 1 year. Nausea occurs mostly in the first 4 weeks, during dose escalation, and is generally of mild intensity. Nausea and vomiting are generally tolerable and accepted as side effects of treatment. Considerable variation in the reporting rates of nausea and vomiting in individual countries was apparent in this trial, suggesting differences in reporting. Methods of improving the consistency in adverse-event reporting are warranted. Specifically, more accurate ways of collecting transient or intermittent adverse events and precise duration periods should be incorporated in future trials, with greater attention to linguistic and cultural differences.

References

Mayer MA, Hocht C, Puyo A, Taira CA . Recent advances in obesity pharmacotherapy. Curr Clin Pharmacol 2009; 4: 53–61.

Murray CJL, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, Ezzati M et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380: 2197–2223.

Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, Gail MH . Cause-specific excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. J Am Med Assoc 2007; 298: 2028–2037.

Kaukua J, Pekkarinen T, Sane T, Mustajoki P . Health-related quality of life in obese outpatients losing weight with very-low-energy diet and behaviour modification: a 2-y follow-up study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003; 27: 1072–1080.

Hassan MK, Joshi AV, Madhavan SS, Amonkar MM . Obesity and health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional analysis of the US population. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003; 27: 1227–1232.

Counterweight Project Team. Evaluation of the Counterweight Programme for obesity management in primary care: a starting point for continuous improvement. Br J Gen Pract 2008; 58: 548–554.

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 393–403.

National Institutes of Health. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults—The Evidence Report. Obes Res 1998; 6 (Suppl 2): 51S–209S.

Mertens IL, Van Gaal LF . Overweight, obesity, and blood pressure: the effects of modest weight reduction. Obes Res 2000; 8: 270–278.

Neter JE, Stam BE, Kok FJ, Grobbee DE, Geleijnse JM . Influence of weight reduction on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hypertension 2003; 42: 878–884.

Look AHEAD Research Group Wing RR . Long-term effects of a lifestyle intervention on weight and cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus: four-year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170: 1566–1575.

Padwal RS, Majumdar SR . Drug treatments for obesity: orlistat, sibutramine, and rimonabant. Lancet 2007; 369: 71–77.

Astrup A . Drug management of obesity - efficacy versus safety. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 288–290.

Field BC, Wren AM, Cooke D, Bloom SR . Gut hormones as potential new targets for appetite regulation and the treatment of obesity. Drugs 2008; 68: 147–163.

Flint A, Raben A, Astrup A, Holst JJ . Glucagon-like peptide 1 promotes satiety and suppresses energy intake in humans. J Clin Invest 1998; 101: 515–520.

Meeran K, O'Shea D, Edwards CM, Turton MD, Heath MM, Gunn I et al. Repeated intracerebroventricular administration of glucagon-like peptide-1-(7-36) amide or exendin-(9-39) alters body weight in the rat. Endocrinology 1999; 140: 244–250.

Gutzwiller JP, Goke B, Drewe J, Hildebrand P, Ketterer S, Handschin D et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1: a potent regulator of food intake in humans. Gut 1999; 44: 81–86.

Zander M, Madsbad S, Madsen JL, Holst JJ . Effect of 6-week course of glucagon-like peptide 1 on glycaemic control, insulin sensitivity, and beta-cell function in type 2 diabetes: a parallel-group study. Lancet 2002; 359: 824–830.

Tang-Christensen M, Larsen PJ, Goke R, Fink-Jensen A, Jessop DS, Moller M et al. Central administration of GLP-1-(7-36) amide inhibits food and water intake in rats. Am J Physiol 1996; 271: R848–R856.

Turton MD, O'Shea D, Gunn I, Beak SA, Edwards CM, Meeran K et al. A role for glucagon-like peptide-1 in the central regulation of feeding. Nature 1996; 379: 69–72.

Williams DL, Baskin DG, Schwartz MW . Evidence that Intestinal Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Plays a Physiological Role in Satiety. Endocrinology 2009; 150: 1680–1687.

Flint A, Raben A, Ersboll AK, Holst JJ, Astrup A . The effect of physiological levels of glucagon-like peptide-1 on appetite, gastric emptying, energy and substrate metabolism in obesity. Int J Obes 2001; 25: 781–792.

Garber A, Henry R, Ratner R, Garcia-Hernandez PA, Rodriguez-Pattzi H, Olvera-Alvarez I et al. Liraglutide versus glimepiride monotherapy for type 2 diabetes (LEAD-3 Mono): a randomised, 52-week, phase III, double-blind, parallel-treatment trial. Lancet 2009; 373: 473–481.

Vilsboll T, Zdravkovic M, Le-Thi T, Krarup T, Schmitz O, Courreges JP et al. Liraglutide, a long-acting human glucagon-like peptide-1 analog, given as monotherapy significantly improves glycemic control and lowers body weight without risk of hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 1608–1610.

Astrup A, Rossner S, Van Gaal L, Rissanen A, Niskanen L, Al Hakim M et al. Effects of liraglutide in the treatment of obesity: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet 2009; 374: 1606–1616.

Astrup A, Carraro R, Finer N, Harper A, Kunesova M, Lean ME et al. Safety, tolerability and sustained weight loss over 2 years with the once-daily human GLP-1 analog, liraglutide. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011; 36: 843–854.

Garber AJ . Incretin-based therapies in the management of type 2 diabetes: rationale and reality in a managed care setting. Am J Manag Care 2010; 16 (7 Suppl): S187–S194.

Isidro ML, Cordido F . Drug Treatment of obesity: Established and emerging therapies. Mini-Rev Med Chem 2009; 9: 664–673.

Davies MJ, Kela R, Khunti K . Liraglutide - overview of the preclinical and clinical data and its role in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diab Obesity Metabol 2011; 13: 207–220.

World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2000; 284: 3043–3045.

Lean ME, James WP . Prescription of diabetic diets in the 1980s. Lancet 1986; 1: 723–725.

Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Kosloski KD, Williams GR . Development of a brief measure to assess quality of life in obesity. Obes Res 2001; 9: 102–111.

Joelson S, Joelson IB, Wallander MA . Geographical variation in adverse event reporting rates in clinical trials. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 1997; 6 (Suppl 3): S31–S35.

Raisch DW, Troutman WG, Sather MR, Fudala PJ . Variability in the assessment of adverse events in a multicenter clinical trial. Clin Ther 2001; 23: 2011–2020.

Barrera JG, Sandoval DA, D'Alessio DA, Seeley RJ . GLP-1 and energy balance: an integrated model of short-term and long-term control. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011; 7: 507–516.

Williams DL . Minireview: Finding the sweet spot: Peripheral versus central glucagon-like peptide 1 action in feeding and glucose homeostasis. Endocrinology 2009; 150: 2997–3001.

Horowitz M, Flint A, Jones KL, Hindsberger C, Rasmussen MF, Kapitza C et al. Effect of the once-daily human GLP-1 analogue liraglutide on appetite, energy intake, energy expenditure and gastric emptying in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2012; 97: 258–266.

Flint A, Kapitza C, Zdravkovic M . The once-daily human GLP-1 analogue liraglutide impacts appetite and energy intake in patients with type 2 diabetes after short-term treatment. Diab Obes Metabol 2013. doi: 10.1111/dom.12108.

Seimon RV, Lange K, Little TJ, Brennan IM, Pilichiewicz AN, Feltrin KL et al. Pooled-data analysis identifies pyloric pressures and plasma cholecystokinin concentrations as major determinants of acute energy intake in healthy, lean men. Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 92: 61–68.

Nauck MA, Meier JJ . Glucagon-like peptide 1 and its derivatives in the treatment of diabetes. Regul Pept 2005; 128: 135–148.

Vilsboll T, Krarup T, Madsbad S, Holst JJ . No reactive hypoglycaemia in Type 2 diabetic patients after subcutaneous administration of GLP-1 and intravenous glucose. Diabet Med 2001; 18: 144–149.

Neumiller JJ, Campbell RK . Liraglutide: a once-daily incretin mimetic for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Pharmacother 2009; 43: 1433–1444.

Orskov C, Poulsen SS . M°ller M, Holst JJ. Glucagon-like peptide I receptors in the subfornical organ and the area postrema are accessible to circulating glucagon-like peptide I. Diabetes 1996; 45: 832–835.

Nauck MA, Kemmeries G, Holst JJ, Meier JJ . Rapid tachyphylaxis of the glucagon-like peptide 1-induced deceleration of gastric emptying in humans. Diabetes 2011; 60: 1561–1565.

Jelsing J, Vrang N, Hansen G, Ravn K, Tang-Christensen M, Knudsen LB . Liraglutide: Short lived effect on gastric emptying - long lasting effects on body-weight. Diab Obes Metabol 2012; 14: 531–538.

Hussain Z . Quigley EMM. Gastrointestinal issues in the assessment and management of the obese patient. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 3: 559–569.

Acknowledgements

We thank the study participants and the members of the NN8022-1807 study group, their staff and clinical trial personnel. We also thank Angela Harper, who provided medical writing services on behalf of Novo Nordisk A/S. The investigators are grateful to Novo Nordisk A/S for permitting access to statistical analyses and detailed data on adverse events, which are not commonly presented in clinical trials.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Liraglutide is a Novo Nordisk A/S proprietary compound under development for the treatment of obesity. No payments were made to the authors for the present paper. MEJL has done commercially sponsored research and paid lecturing for Novo Nordisk A/S. RC has done paid lecturing and commercially sponsored research for Astra Zeneca, Novo Nordisk A/S, Novartis and Sanofi. NF was an advisory board member and has done paid lecturing and commercially sponsored research for Novo Nordisk A/S, Abbott Laboratories, and Sanofi, and is an advisory board member for Pfizer, Allergan, Arena, Vivus and Takeda. HH and MLL are employees of Novo Nordisk A/S and own stock in the company. SR has done paid lecturing and commercially sponsored research for Novo Nordisk A/S. LVG was an advisory board member for Novo Nordisk A/S, Eli Lilly, Astra Zeneca and Sanofi, and has done commercially sponsored research for Novo Nordisk A/S. AA has done commercially sponsored research for Novo Nordisk A/S, was an advisory board member for Novo Nordisk A/S and Merck Sharpe and Dome and was consultant to Novo Nordisk A/S, 7TM Pharma, Neurosearch, Johnson and Johnson, and Takeda Global Research & Development.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on International Journal of Obesity website

Supplementary information

Appendix

Appendix

Members of the NN8022-1807 Investigators

Belgium: Luc Van Gaal. Czech Republic: Stepan Svacina, Marie Kunesova. Denmark: Arne Astrup, Bjørn Richelsen, Kjeld Hermansen, Steen Madsbad. Finland: Aila Rissanen, Leo Niskanen, Markku Savolainen. The Netherlands: Mazin Al Hakim. Spain: Guillem Cuatrecasas Cambra, Belén Sádaba, Raffaele Carraro, Basilio Moreno. Sweden: Stephan Rössner, Martin Ridderstråle. United Kingdom: Michael Lean, Nick Finer, Mike Sampson.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lean, M., Carraro, R., Finer, N. et al. Tolerability of nausea and vomiting and associations with weight loss in a randomized trial of liraglutide in obese, non-diabetic adults. Int J Obes 38, 689–697 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.149

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.149

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The dual amylin and calcitonin receptor agonist KBP-089 and the GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide act complimentarily on body weight reduction and metabolic profile

BMC Endocrine Disorders (2021)

-

Effectiveness of liraglutide 3 mg for the treatment of obesity in a real-world setting without intensive lifestyle intervention

International Journal of Obesity (2021)

-

Danuglipron (PF-06882961) in type 2 diabetes: a randomized, placebo-controlled, multiple ascending-dose phase 1 trial

Nature Medicine (2021)

-

Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Anti-Obesity Treatment: Where Do We Stand?

Current Obesity Reports (2021)

-

Gastrointestinal Tolerability of Once-Weekly Dulaglutide 3.0 mg and 4.5 mg: A Post Hoc Analysis of the Incidence and Prevalence of Nausea, Vomiting, and Diarrhea in AWARD-11

Diabetes Therapy (2021)