Abstract

The relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) is U-shaped, whereas alcohol drinking is linearly associated with blood pressure, and the CVD risk also increases linearly according to blood pressure level. Accordingly, we investigated the net effect of alcohol consumption and hypertension on CVD and its subtypes in this study. A 13-year prospective study of 2336 Japanese men who were free from CVD was performed; ex-drinkers were excluded. The participants were divided into eight groups classified by the combination of the presence of hypertension (systolic/diastolic blood pressure ⩾140/90 mm Hg) and alcohol consumption (never-, current- (light, moderate and heavy) drinkers). Multivariate-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for the incidence of CVD, coronary artery disease (CAD) and stroke due to the combination of hypertension and alcohol consumption were calculated and compared with non-hypertensive never-drinkers. The HRs for CVD and its subtypes were higher in hypertensives than those in non-hypertensives; in hypertensives without medication for hypertension, the relationship between alcohol consumption and the risks for CVD and CAD was U-shaped, with the highest and most significant increase in never-drinkers. The risk for total stroke was the highest in heavy-drinkers, which was significant. In non-hypertensives, there was no evident increase or decrease in the HRs for CVD and its subtypes in drinkers. Accordingly, controlling blood pressure is important to prevent CVD. In hypertensives, heavy drinking should be avoided to prevent CVD, although light-to-moderate drinking could be protective for CAD. Furthermore, in non-hypertensives, drinkers may need to continuously monitor their blood pressure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been reported to be U-shaped in previous studies.1, 2 However, drinking alcohol is also well known to be positively associated with the development of hypertension.3 Alcohol consumption is linearly related to increased blood pressure,4, 5 and the CVD risk also linearly increases according to the blood pressure level.6 Thus, several previous studies have investigated the relationships among alcohol consumption, hypertension and CVD risk in hypertensive patients,7, 8, 9 but few studies were performed in the general population including both hypertensives and non-hypertensives.

Japanese men have been reported to drink more alcohol,10 have a higher prevalence of hypertension,11, 12 and have a higher prevalence of stroke13 than Westerners. Therefore, an investigation of the net effect of hypertension and alcohol consumption on the risk for CVD and its subtypes is important in Asian populations, including the Japanese.

To investigate the relationships among alcohol consumption, hypertension and the risk for CVD and its subtypes, a 13-year cohort study of an urban Japanese male population was conducted.

Methods

Study participants

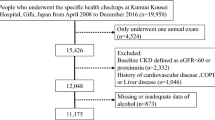

The Suita study,14, 15 a cohort study of CVD, was established in 1989. In this study, 6485 participants who were randomly selected from the municipal population registry participated in a baseline survey at the National Cardiovascular Center (NCVC, currently, National Cerebral Cardiovascular Center) between September 1989 and February 1994. The present study excluded 821 participants who had a past history of CVD at the baseline survey or who were lost to follow-up, as well as 3093 female participants because the alcohol consumption of women was much less than that of men (prevalence of drinking alcohol >23 g ethanol per day in women: 6.3%). In addition, 235 men were excluded for the following reasons: non-fasting visit (n=83), missing information at the baseline survey (n=58) and being an ex-drinker (n=94). The data for the remaining 2336 men aged 30–79 years were then analyzed. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the NCVC.

Baseline examination

Well-trained nurses obtained information on smoking, alcohol consumption and the medical histories of the participants. The assessment of alcohol consumption was previously reported.16 Briefly, current drinkers were asked about the frequency of alcohol consumption during a typical week and the total alcohol intake on each occasion, and the alcohol intake per week was calculated. This value was then divided by seven to obtain the average alcohol intake per day. The usual daily intake of alcohol was assessed in units of ‘gou’ (a traditional Japanese unit of measurement, corresponding to 23 g of ethanol) and then converted to grams of ethanol per day. In the present study, half a gou was defined as one drink (11.5 g of ethanol), a value nearly equal to a ‘standard drink’ in other countries.17 According to the guidelines for lifestyle changes in Japan (Health Japan 21), the recommended amount of alcohol consumption for men was not more than two drinks per day.18 Thus, the participants were classified as never-drinkers, light-drinkers (⩽2.0 drinks per day), moderate-drinkers (>2.0 and ⩽4.0 drinks per day) and heavy-drinkers (>4.0 drinks per day).

Well-trained physicians measured the participants’ blood pressure in the right arm three times with the participant in a seated position after 5 min rest using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer. The average of the second and third measurements was used in the analyses. Height in socks and weight in light clothing were measured. The body mass index was calculated as weight (kg) divided by the square of height (m2). Blood samples were collected at the NCVC after the participants had fasted for at least 8 h. The samples were centrifuged immediately, and a routine blood examination that included serum total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglyceride and glucose levels was then conducted.

Follow-up and endpoint determination

The follow-up method has been described elsewhere.14, 15 Briefly, the endpoints of the present study were as follows: (1) the date of the first stroke or coronary artery disease (CAD) event; (2) the date of death; (3) the date of leaving Suita city; and (4) 31 December 2007. The survey for the stroke and CAD events involved checking the health status of the participants by repeated clinical visits to the NCVC or interview by mail or telephone, followed by checking the in-hospital medical records of the participants who were suspected of having had a stroke or CAD. The criteria for stroke were defined according to the US National Survey of Stroke criteria.19 For each stroke subtype (cerebral infarction (thrombotic or embolic), intracerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage), a definitive diagnosis was established based on computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging or autopsy. In the present study, cerebral infarction was defined as an ischemic stroke, and intracerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage were defined as hemorrhagic strokes. The criteria for myocardial infarction were defined according to the criteria of the Monitoring Trends and Determinants of Cardiovascular Disease (MONICA) project,20 which requires evidence from an electrocardiogram, cardiac enzymes and/or autopsy. In addition to acute myocardial infarction, the criteria for a diagnosis of CAD included sudden cardiac death within 24 h after the onset of acute symptoms or CAD followed by coronary artery bypass or angioplasty. Furthermore, to complete the surveillance for fatal strokes and myocardial infarctions, a systematic search for death certificates was conducted.

Statistical analyses

Hypertension was defined as an average systolic/diastolic blood pressure ⩾140/90 mm Hg.21 Dyslipidemia was defined as total cholesterol ⩾5.69 mmol l−1 (220 mg dl−1) and/or HDL-C <1.03 mmol l−1 (40 mg dl−1) and/or triglyceride ⩾1.69 mmol l−1 (150 mg dl−1)22 and/or current use of oral medication for dyslipidemia. Diabetes was defined as a fasting blood glucose ⩾7.06 mmol l−1 (126 mg dl−1)23 and/or current use of insulin or oral medication for diabetes.

To show the baseline risk characteristics of the six groups classified by alcohol drinking status (never, light, moderate and heavy) and the presence of hypertension (absent and present), the mean or median was calculated for continuous variables, and the percentage was calculated for dichotomous variables.

The Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the age- and multivariate-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals of alcohol consumption in those with and without hypertension for the incidence of CVD, CAD, stroke and stroke subtypes after adjustment for age, body mass index, the presence of dyslipidemia and diabetes (absent or present) and smoking status (current or non-current). When the HRs were calculated, never-drinkers without hypertension were defined as the ‘reference’ group. The estimation of the HRs was also performed after excluding the participants with medication for hypertension at the baseline survey.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) statistical software version 15.0 J (SPSS, Tokyo, Japan), and P<0.05 (two-tailed) was considered significant.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 55±13 years. Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the participants divided into eight groups classified by the combination of the presence of hypertension and alcohol consumption. The participants with hypertension were older than those without hypertension, and current drinkers were younger than never-drinkers. The percentage of current smoking was the highest among heavy-drinkers both in those with and without hypertension. In those with hypertension, the triglyceride median increased according to alcohol consumption.

The mean follow-up period was 13 years, and 109 CAD, 78 ischemic stroke and 29 hemorrhagic stroke events occurred. Table 2 shows the age- and multivariate-adjusted HRs (95% confidence intervals) for CVD and its subtypes of the eight groups classified by the combination of alcohol consumption and the presence of hypertension compared with never-drinkers without hypertension in all participants. In non-hypertensives, the HRs for CVD and CAD in current drinkers were consistently lower than that in the reference group. Additionally, the HRs for total and ischemic stroke were similar or slightly higher in the light-drinkers and lower in the moderate- and heavy-drinkers than those in the reference group. However, there was no evident increase or decrease in the HRs for CVD and its subtypes. Among hypertensives, the HRs for CVD and CAD were consistently higher than those in the reference group, and the relationship between alcohol consumption and the risks for CVD and CAD was U-shaped, with the highest and most significant increase in never-drinkers. The HRs for total and ischemic stroke were also consistently higher than those in the reference group, with the highest and most significant increase in heavy-drinkers for total stroke and in light-drinkers for ischemic stroke. For hemorrhagic stroke, the risk associated with alcohol consumption could not be assessed because of the small number of these events (data not shown in the table).

Table 3 shows the age- and multivariate-adjusted HRs (95% confidence intervals) for CVD and its subtypes of the eight groups in the participants without medication for hypertension at the baseline survey. For CVD and CAD, the results were similar to those in Table 2. For total and ischemic stroke, the results in non-hypertensives were also similar to those in Table 2; in hypertensives, the HRs were consistently increased in all groups compared with those in the reference group, and an increase in the HR for both total and ischemic stroke was statistically significant and the highest in heavy-drinkers.

When we additionally adjusted for pulse pressure in the estimation of the HRs presented in Tables 2 and 3, the results were equivalent, although the HRs for CAD in hypertensives were slightly attenuated (data not shown).

Discussion

In the present study, the multivariate-adjusted HRs for CVD and its subtypes were consistently higher in the hypertensive participants compared with the non-hypertensive never-drinkers, irrespective of alcohol consumption. In hypertensives without medication for hypertension, the relationship between alcohol consumption and the risks for CVD and CAD was U-shaped, with the highest and most significant increase in never-drinkers. The risk for total and ischemic stroke was the highest in heavy-drinkers, which was significant. In non-hypertensives, there was no evident increase or decrease in the HRs for CVD and its subtypes in drinkers.

One of the strengths of this study was that we compared the risk for CVD and its subtypes due to alcohol consumption among those with and without hypertension. Another strength was that we also estimated the HRs only among the individuals without medication for hypertension at the baseline survey, although the number of events was small. Furthermore, this study is the first to show the relationships among alcohol consumption, hypertension diagnosed by the current definition and the risk for CAD in an Asian population. Although Kiyohara et al.24 investigated the net effect of alcohol consumption on ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke stratified by the presence of hypertension in a Japanese population (Hisayama study), they did not investigate the risk for CAD, and their diagnosis of hypertension was defined as 160/95 mm Hg.

For CAD, the results in the present study were similar to those in previous studies involving hypertensive Western populations. In the previous studies, light-to-moderate alcohol consumption in hypertensives was associated with a reduced risk for CVD mortality or a reduced incidence of myocardial infarction.7, 8, 9 A possible mechanism of reduced risk for CAD in hypertensive drinkers in the present study might be as follows: although they were under high risk for hypertension because of lineally increasing blood pressure due to alcohol drinking4, 5 and high risk for CAD due to hypertension,6 there might be cardio-protective effects, such as decreased platelet aggregation25 and increased fibrinolytic activity.26 An increase in the serum level of HDL-C may be another cardio-protective effect of alcohol.27 Such cardio-protective effects of alcohol drinking and the relatively higher incidence of CAD compared with that in the previous study in Japan28 might explain the clear U-shaped relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk for CVD among hypertensives in the present study.

With respect to stroke, Kiyohara et al.24 investigated the combined effects of alcohol drinking and hypertension on stroke in a prospective study of the general Japanese population. The participants were classified as non-drinkers, light-drinkers (<34 g of ethanol per day) and heavy-drinkers (⩾34 g of ethanol per day) and were followed up for 26 years. Among the hypertensive subjects (⩾160/95 mm Hg), the risk for cerebral hemorrhage was significantly increased in heavy-drinkers compared with non-drinkers; the relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk for cerebral infarction was U-shaped, with a significant increase in heavy-drinkers compared with light-drinkers. However, an increase in the risk for hemorrhagic and cerebral stroke was not shown in any drinkers among the non-hypertensives (<160/95 mm Hg). It was observed both in the previous and present studies that the highest risk for stroke was in hypertensive heavy-drinkers, although there was no U-shaped pattern for cerebral infarction herein.

However, these results in Japanese hypertensives were not consistent with those in Western populations,7, 8 that is, the risk for stroke was lower in any drinkers compared with never-drinkers in Westerners.7, 8 This inconsistency between the Western and Japanese populations might be due to a difference in the incidence of stroke events and in the percentage of stroke subtypes. Specifically, the incidence of hemorrhagic stroke, which could be affected by heavy alcohol drinking,2, 29 and hypertension30, 31 has been much lower than that of ischemic stroke in Western populations.32 Furthermore, for ischemic stroke, the frequency of cortical infarction or cerebral embolism was high in Western populations,33, 34 and a pathological study revealed that moderate alcohol intake has a weak inverse association with atherosclerosis in large, cerebral arteries.35 Thus, even in a hypertensive condition, the risk for stroke associated with alcohol consumption could be low or not evidently increased in Western populations. In contrast, in a Japanese population, the incidence of hemorrhagic stroke is considered to be higher than that in Western populations.2, 31 Additionally, lacunar infarction due to small-vessel disease was the most common among Japanese individuals.36 Moreover, a pathological study revealed that moderate alcohol intake did not have an inverse association with atherosclerosis in small cerebral arteries.35 Thus, these factors might have an influence on the additive effect of alcohol and hypertension on stroke in the Japanese population.24

In non-hypertensive participants, neither an evident increase nor decrease was shown in the risk for CAD and stroke with increased alcohol consumption. As the numbers of non-hypertensive participants and CVD event cases were small in the present study, the risk for CVD and its subtypes of alcohol drinking in non-hypertensives should be investigated in other large-scale prospective studies.

As shown in the present study, hypertension is the key to determine the risk for CVD and its subtypes. As heavy drinking was associated with a significant increase in the risk for both CAD and stroke in hypertensives, individuals with hypertension should avoid heavy alcohol drinking. In addition, lowering high levels of alcohol consumption is associated with a reduction in blood pressure.37 Thus, a reduction in alcohol consumption is expected to be followed by both a decrease in blood pressure and particularly a decrease in the risk for stroke, although the association between the reduction of alcohol consumption in hypertensives and the risk for stroke incidence should be examined in future studies among Asian populations. In non-hypertensives, drinkers need to pay attention to their blood pressure and avoid heavy drinking, not only for the prevention of CVD, but also for the prevention of other alcohol-induced diseases.

The present study had several limitations. First, the relationships among alcohol drinking, hypertension and hemorrhagic stroke could not be assessed because of the small number of cases. In addition, we could not assess the risk for CVD and its subtypes in moderate- and heavy-drinkers separately with and without hypertension due to the small number of events. Second, single blood pressure measurements and a single questionnaire for alcohol consumption at the baseline survey might have underestimated the relationships among alcohol drinking, hypertension and CVD due to regression dilution bias.38 Third, the effects of the type of alcoholic beverage17 and genetic differences, such as acetaldehyde dehydrogenase genotypes,39 could not be investigated. Fourth, we potentially could not fully remove the influence of age differences among the groups at the baseline, although we adjusted for age in the estimation of the HRs.

In conclusion, compared with never-drinkers without hypertension, the risks for CVD, CAD, stroke and ischemic stroke were increased in those with hypertension, irrespective of alcohol consumption. The risk for CAD was the highest in hypertensive never-drinkers, whereas the risk for stroke was the highest in hypertensive heavy-drinkers. In non-hypertensives, there was no evident increase or decrease in the HRs for CVD and its subtypes in drinkers. Accordingly, controlling blood pressure is important to prevent CVD. In hypertensives, heavy drinking should be avoided to prevent CVD, although light-to-moderate drinking could be protective for CAD. Furthermore, in non-hypertensives, drinkers may need to continuously monitor their blood pressure.

Change history

07 January 2012

This article has been corrected since Advance Online Publication, and a corrigendum is also printed in this issue.

References

Thun MJ, Peto R, Lopez AD, Monaco JH, Henley SJ, Heath CW, Doll R . Alcohol consumption and mortality among middle-aged and elderly U.S. adults. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 1705–1714.

Ikehara S, Iso H, Toyoshima H, Date C, Yamamoto A, Kikuchi S, Kondo T, Watanabe Y, Koizumi A, Wada Y, Inaba Y, Tamakoshi A, Japan Collaborative Cohort Study Group. Alcohol consumption and mortality from stroke and coronary heart disease among Japanese men and women. The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. Stroke 2008; 39: 2936–2942.

MacMahon S . Alcohol consumption and hypertension. Hypetension 1987; 9: 111–121.

Okubo Y, Miyamoto T, Suwazono Y, Kobayashi E, Nogawa K . Alcohol consumption and blood pressure in Japanese men. Alcohol 2001; 23: 149–156.

Wakabayashi I, Araki Y . Influences of gender and age on relationships between alcohol drinking and atherosclerotic risk factors. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2010; 34: S54–S60.

Kokubo Y, Kamide K, Okamura T, Watanabe M, Higashiyama A, Kawanishi K, Okayama A, Kawano Y . Impact of high-normal blood pressure on the risk of cardiovascular disease in a Japanese Urban Cohort; The Suita Study. Hypertension 2008; 52: 652–659.

Malinski MK, Sesso HD, Lopez-Jimenez F, Buring JE, Gaziano JM . Alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease mortality in hypertensive men. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164: 623–628.

Palmer AJ, Fletcher AE, Bulpitt CJ, Beevers DG, Coles EC, Ledingham JG, Petrie JC, Webster J, Dollery CT . Alcohol intake and cardiovascular mortality in hypertensive patients: report from the Department of Health Hypertension Care Computing Project. J Hypertens 1995; 13: 957–964.

Beulens JW, Rimm EB, Ascherio A, Spiegelman D, Hendriks HF, Mukamal KJ . Alcohol consumption and risk for coronary heart disease among men with hypertension. Ann Intern Med 2007; 146: 10–19.

Ueshima H . Do the Japanese drink less alcohol than other peoples?: the finding from INTERMAP. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi 2005; 40: 27–33.

Health and Welfare Statistics Association. Lifestyle-related disease. In: Health and Welfare Statistics Association (eds). (2010/2011) Journal of Health and Welfare Statistics Vol. 57. Okumura Insatsu: Tokyo, Japan, 2010 pp. 18.

Fields LE, Burt VL, Cutler JA, Hughes J, Roccella EJ, Sorlie P . The burden of adult hypertension in the United States 1999 to 2000. A rising tide. Hypertension 2004; 44: 398–404.

Zhou BF, Stamler J, Dennis B, Moag-Stahlberg A, Okuda N, Robertson C, Zhao L, Chan Q, Elliott P, INTERMAP Research Group. Nutrient intakes of middle-aged men and women in China, Japan, United Kingdom, and United States in the late 1990s: the INTERMAP study. J Hum Hypertens 2003; 17: 623–630.

Okamura T, Kokubo Y, Watanabe M, Higashiyama A, Miyamoto Y, Yoshimasa Y, Okayama A . Low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol and non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol and the incidence of cardiovascular disease in an urban Japanese cohort study: the Suita study. Atherosclerosis 2009; 203: 587–592.

Kokubo Y, Okamura T, Watanabe M, Higashiyama A, Ono Y, Miyamoto Y, Furukawa Y, Kamide K, Kawanishi K, Okayama A, Yoshimasa Y . The combined impact of blood pressure category and glucose abnormality on the incidence of cardiovascular diseases in a Japanese urban cohort: the Suita Study. Hypertens Res 2010; 33: 1238–1243.

Higashiyama A, Wakabayashi I, Ono Y, Watanabe M, Kokubo Y, Okayama A, Miyamoto Y, Okamura T . Association with serum gamma-glutamyltransferase levels and alcohol consumption on stroke and coronary artery disease: the Suita study. Stroke 2011; 42: 1764–1767.

Okamura T, Tanaka T, Yoshita K, Chiba N, Takebayashi T, Kikuchi Y, Tamaki J, Tamura U, Minai J, Kadowaki T, Miura K, Nakagawa H, Tanihara S, Okayama A, Ueshima H, HIPOP-OHP research group. Specific alcoholic beverage and blood pressure in a middle-aged Japanese population: the High-risk and Population Strategy for Occupational Health Promotion (HIPOP-OHP) Study. J Hum Hypertens 2004; 18: 9–16.

Japan Health Promotion and Fitness Foundation. Health Japan 21. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Report on Health Japan 21 Plan Study Committee and Health Japan 21 Plan Development Committee.

Walker AE, Robins M, Weinfeld FD . The National Survey of Stroke. Clinical findings. Stroke 1981; 12 (suppl 1): I13–I44.

World Health Organization. Document for meeting of MONICA Principal Investigations. In: WHO (ed.). MONICA Project: Event Registration Data Component, MONICA Manual, Version 1.1 S-4. WHO: Geneva, USA, 1986 pp. 9–11.

Ogihara T, Kikuchi K, Matsuoka H, Fujita T, Higaki J, Horiuchi M, Imai Y, Imaizumi T, Ito S, Iwao H, Kario K, Kawano Y, Kim-Mitsuyama S, Kimura G, Matsubara H, Matsuura H, Naruse M, Saito I, Shimada K, Shimamoto K, Suzuki H, Takishita S, Tanahashi N, Tsuchihashi T, Uchiyama M, Ueda S, Ueshima H, Umemura S, Ishimitsu T, Rakugi H,, Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee. The Japanese Society of hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2009). Hypertens Res 2009; 32: 3–107.

Teramoto T, Sasaki J, Ueshima H, Egusa G, Kinoshita M, Shimamoto K, Daida H, Biro S, Hirobe K, Funahashi T, Yokote K, Yokode M, Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) Committee for Epidemiology and Clinical Management of Atherosclerosis. Diagnostic criteria for dyslipidemia. Executive summary of Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) guideline for diagnosis and prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases for Japanese. J Atheroscler Thromb 2007; 14: 155–158.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2010. Diabetes Care 2010; 33 (suppl 1): S11–S61.

Kiyohara Y, Kato I, Iwamoto H, Nakayama K, Fujishima M . The impact of alcohol and hypertension on stroke incidence in a general Japanese population. The Hisayama Study. Stroke 1995; 26: 368–372.

Renaud SC, Beswick AD, Fehily AM, Sharp DS, Elwood PC . Alcohol and platelet aggregation: the Caerphilly prospective heart disease study. AmJ Clin Nutr 1992; 55: 1012–1017.

Ridker PM, Vaughan DE, Stampfer MJ, Glynn RJ, Hennekens CH . Association of moderate alcohol consumption and plasma concentration of endogenous tissuetype plasminogen activator. JAMA 1994; 272: 929–933.

Gaziano JM, Buring JE, Breslow JL, Goldhaber SZ, Rosner B, VanDenburgh M, Willett W, Hennekens CH . Moderate alcohol intake, increased levels of high-density lipoprotein and its subfractions, and decreased risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 1829–1834.

Osawa H, Doi Y, Makino H, Ninomiya T, Yonemoto K, Kawamura R, Hata J, Tanizaki Y, Iida M, Kiyohara Y . Diabetes and hypertension markedly increased the risk of ischemic stroke associated with high serum resistin concentration in a general Japanese population: the Hisayama Study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2009; 8: 60.

Klatsky AL, Armstrong MA, Friedman GD, Sidney S . Alcohol drinking and risk of hemorrhagic stroke. Neuroepidemiology 2002; 21: 115–122.

Inoue R, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Metoki H, Asayama K, Kanno A, Obara T, Hirose T, Hara A, Hoshi H, Totsune K, Satoh H, Kondo Y, Imai Y . Stroke risk of blood pressure indices determined by home blood pressure measurement: the Ohasama study. Stroke 2009; 40: 2859–2861.

Woo D, Haverbusch M, Sekar P, Kissela B, Khoury J, Schneider A, Kleindorfer D, Szaflarski J, Pancioli A, Jauch E, Moomaw C, Sauerbeck L, Gebel J, Broderick J . Effect of untreated hypertension on hemorrhagic stroke. Stroke 2004; 35: 1703–1708.

Djoussé L, Ellison RC, Beiser A, Scaramucci A, D'Agostino RB, Wolf PA . Alcohol consumption and risk of ischemic stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke 2002; 33: 907–912.

Mohr JP, Caplan LR, Melski JW, Goldstein RJ, Duncan GW, Kistler JP, Pessin MS, Bleich HL . The harvard cooperative stroke registry: a prospective registry. Neurology 1978; 28: 754–762.

Bogousslavsky J, Melle GV, Regli F . The Lausanne Stroke Registry: analysis of 1,000 consecutive patients with first stroke. Stroke 1988; 19: 1083–1092.

Reed DM, Resch JA, Hayashi T, MacLean C, Yano K . A prospective study of cerebral artery atherosclerosis. Stroke 1988; 19: 820–825.

Turin TC, Kita Y, Rumana N, Nakamura Y, Takashima N, Ichikawa M, Sugihara H, Morita Y, Hirose K, Okayama A, Miura K, Ueshima H . Ischemic stroke subtypes in a Japanese population: Takashima Stroke Registry, 1988–2004. Stroke 2010; 41: 1871–1876.

Xin X, He J, Frontini MG, Ogden LG, Motsamai OI, Whelton PK . Effects of alcohol reduction on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hypertension 2001; 38: 1112–1117.

MacMahon S, Peto R, Cutler J, Collins R, Sorlie P, Neaton J, Abbott R, Godwin J, Dyer A, Stamler J . Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet 1990; 335: 765–774.

Amamoto K, Okamura T, Tamaki S, Kita Y, Tsujita Y, Kadowaki T, Nakamura Y, Ueshima H . Epidemiologic study of the association of low-Km mitochondrial acetaldehyde dehydrogenase genotypes with blood pressure level and the prevalence of hypertension in a general population. Hypertens Res 2002; 25: 857–864.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Suita Medical Foundation and the Suita City Health Center. We also thank the researchers and the paramedical staff in the Department of Preventive Cardiology, NCVC, for their excellent medical examinations and follow-up surveys. Finally, we would like to thank Satuki-Junyukai, the society of the members of the Suita study. This study was supported by the Intramural Research Fund of the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center (22-4-5), by a Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Health and Labor Sciences research grants, Japan (the Comprehensive Research on Cardiovascular and Life-Style Related Diseases: H23-Junkankitou (Seishuu)-Ippan-005), and by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research B 21390211 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Higashiyama, A., Okamura, T., Watanabe, M. et al. Alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease incidence in men with and without hypertension: the Suita study. Hypertens Res 36, 58–64 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2012.133

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2012.133

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The protective effect of alcohol consumption on the incidence of cardiovascular diseases: is it real? A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies conducted in community settings

BMC Public Health (2020)

-

The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2019)

Hypertension Research (2019)

-

Weingenuss und Prävention der koronaren Herzkrankheit

Herz (2016)

-

The relationship between mild alcohol consumption and mortality in Koreans: a systematic review and meta-analysis

BMC Public Health (2015)

-

Chapter 4. Lifestyle modifications

Hypertension Research (2014)