Abstract

Wolbachia is an endocellular bacterium infecting arthropods and nematodes. In arthropods, it invades host populations through various mechanisms, affecting host reproduction, the most common of which being cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI). CI is an embryonic mortality occurring when infected males mate with uninfected females or females infected by a different Wolbachia strain. This phenomenon is observed in Drosophila simulans, an intensively studied Wolbachia host, harbouring at least five distinct bacterial strains. In this study, we investigate various aspects of the Wolbachia infections occurring in two continental African populations of D. simulans: CI phenotype, phylogenetic position based on the wsp gene and associated mitochondrial haplotype. From the East African population (Tanzania), we show that (i) the siIII mitochondrial haplotype occurs in continental populations, which was unexpected based on the current views of D. simulans biogeography, (ii) the wKi strain (that rescues from CI while being unable to induce it) is very closely related to the CI-inducing strain wNo, (iii) wKi and wNo might not derive from a unique infection event, and (iv) wKi is likely to represent the same entity as the previously described wMa variant. In the West African population (Cameroon), the Wolbachia infection was found identical to the previously described wAu, which does not induce CI. This finding supports the view that wAu might be an ancient infection in D. simulans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wolbachia are maternally transmitted endocellular bacteria infecting arthropods and nematodes (reviewed in Stouthamer et al, 1999; Stevens et al, 2001). In arthropods, the infection can result in various alterations of sexuality and reproduction such as feminization (Rigaud, 1997), thelytokous parthenogenesis (Stouthamer, 1997), male killing (Hurst et al, 1999) and cytoplasmic incompatibility (Hoffmann and Turelli, 1997; Charlat et al, 2001). All these phenomena drive infected females to produce more females than uninfected ones, allowing Wolbachia to spread and maintain themselves in hosts' populations. The most common phenomenon, cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI), is observed when infected males mate with uninfected females or with females infected by a different, incompatible Wolbachia strain. In such crosses, fertilization is apparently normal but subsequent mitoses are disrupted, leading to the death of the zygote (Reed and Werren, 1995; Callaini et al, 1996,1997; Lassy and Karr, 1996). Basically, infected cytoplasms are selected for because the eggs laid by infected females are protected from CI, while those laid by uninfected females are not.

The mechanism involved is presently unknown, but CI can be interpreted using the mod/resc model (Werren, 1997), which implies the existence of two bacterial functions: modification (mod) and rescue (resc). The mod function would somehow modify the male pronuclei (Presgraves, 2000), before Wolbachia are shed from maturing sperm, and the resc function would rescue the embryo through an interaction with modified sperm. An egg fertilized with a modified sperm will not develop normally unless a specific resc function is expressed in the egg.

CI is observed in Drosophila simulans, an extensively studied Wolbachia host (reviewed in Merçot and Charlat, 2003), harbouring several different bacterial variants. Three variants have been shown to induce CI when present in males and to rescue from their own effect when present in females: wRi (Hoffmann et al, 1986), wHa (O'Neill and Karr, 1990) and wNo (Merçot et al, 1995). Three other variants have been described that do not seem to induce CI when present in males: wMa (Rousset and Solignac, 1995), wAu (Hoffmann et al, 1996) and wKi (Merçot and Poinsot, 1998a; Poinsot and Merçot, 1999). Furthermore, wKi has been demonstrated to possess a functional resc: eggs infected by wKi are rescued in crosses with wNo-infected males (Merçot and Poinsot, 1998a; Poinsot and Merçot, 1999). Indirect arguments suggest that wMa would show the same phenotype (Bourtzis et al, 1998).

These different variants are not randomly associated with the three very distinct mitochondrial haplo-types that have been described in D. simulans (siI, siII and siIII; Figure 1). This is expected because Wolbachia and mitochondria are transmitted together through the egg cytoplasm so that they should remain associated over time (provided that horizontal and/or paternal transmission of Wolbachia and/or mitochondria are not too frequent). Thus, the wRi and wAu variants are associated with the siII haplo-type (Hale and Hoffmann, 1990; James and Ballard, 2000), the wHa and wNo variants are associated with the siI haplotype (Montchamp-Moreau et al, 1991; Rousset and Solignac, 1995), and the wMa variant is associated with the siIII haplotype (Rousset et al, 1992). As shown here, wKi is also associated with siIII.

Phylogenetic relationships between mitochondrial haplotypes harboured by D. simulans (siI, siII, siIII), D. sechellia (se) and the maI haplotype of D. mauritiana (Satta and Takahata, 1990; Ballard, 2000a,b). se and siI form a monophyletic group, which might be because of the persistence of an ancestral poly-morphism in D. simulans, or to an introgression event. maI and siIII are virtually identical, a pattern most likely because of a well-accepted recent introgression (Solignac and Monnerot, 1986; Ballard, 2000c).

In the present study, two D. simulans populations from the African continent were investigated: one from East Africa (Kilimanjaro, Tanzania), known to be infected by wKi (Merçot and Poinsot, 1998a) and one from West Africa (Yaounde, Cameroon). Three different traits were considered: (i) CI phenotype (the Wolbachia ability to induce CI or to rescue from it), (ii) sequences of the Wolbachia Surface Protein gene and (iii) associated mitochondrial haplotype. Our main conclusions are the following. From the East African population, we show that (i) the siIII mitochondrial haplotype occurs in continental Africa, which was unexpected based on the current views of D. simulans biogeography, (ii) the wKi strain is very closely related to wNo, (iii) wKi and wNo might not derive from a unique infection event, and (iv) wKi is likely to represent the same entity as the previously described wMa variant. In the West African population, the Wolbachia infection was found to be identical to the previously described wAu strain, based on all the traits under study. This finding supports the view that the wAu infection in D. simulans might be ancient, and raises the question of how non-CI-inducing Wolbachia maintain themselves in natural populations.

Materials and methods

Drosophila simulans strains

Reference lines

Agadir is a strain collected in Morocco in 1996, infected by wRi (Poinsot and Merçot, 1999). NHa originates from the Noumea 89 strain, bi-infected by wHa and wNo. Following segregation of the two variants, NHa only bears wHa (Poinsot and Merçot, 1997). N7No also originates from Noumea 89. Following segregation of the two variants, N7No only bears wNo (Merçot and Poinsot, 1998b). Coffs Harbour S20 is an Australian strain founded using flies from a 1993 collection, infected by wAu (Hoffmann et al, 1996). SimO is a naturally uninfected strain from Nasr'allah (Tunisia) (Merçot et al, 1995). STC is an inbred stock from the Seychelles strain (Seychelles archipelago), originally bi-infected by wHa + wNo, cured from its Wolbachia following a tetracycline treatment (Poinsot et al, 2000). ME29 is a D. simulans line transinfected with the Wolbachia wMel, naturally infecting the D. melanogaster Wien5 isofemale line (Poinsot et al, 1998).

Studied lines

Yaounde: 19 isofemale lines have been studied, originating from females collected in Yaounde (Cameroon) in 1997 by B Riera. Kilimanjaro: KC9, K45 and K39 are isofemale lines infected, or originally infected, by wKi. K60 is an isofemale line naturally uninfected. K10P is a mass strain founded using a pool of 10 uninfected isofemale lines. All lines originated from flies collected in 1996 in Tanzania by D Lachaise (Poinsot and Merçot, 1999).

Rearing conditions

During the experiment, all lines were maintained at 25°C in bottles with axenic medium (David, 1962) at low larval competition. For three generations at least before the beginning of CI experiments, all lines concerned were maintained by crossing 20 virgin females aged 4–6 days and 25 virgin males aged 3–4 days in bottles with axenic medium. After 24 h of egg laying, individuals were transferred to a second bottle for another 24 h, before the adults were discarded. Given the laying rates on the strains used, this protocol ensures a low larval competition and (when flies are infected) the maximum expression of CI.

Cytoplasmic incompatibility tests

Individual crosses were carried out using 3-day-old virgin males and 4 to 5-day-old virgin females. Each cross was initiated by placing one male and one female in a vial with axenic medium until mating was observed. The male was then removed and the female was supplied with a laying plate for 48 or 72 h. Upon removal of the female, the eggs were placed at 25°C for 24 h before egg hatch was measured using all eggs. Laying plates containing less than 20 eggs were discarded. All individuals from infected strains were checked by PCR for the presence of Wolbachia using 16S primers (O'Neill et al, 1992) or general wsp primers: 81F and 691R (Braig et al, 1998).

wsp sequencing

DNA was extracted from individually crushed flies, using the crude STE boiling method (O'Neill et al, 1992). The wsp gene was then amplified by PCR using general primers 81F and 691R (Braig et al, 1998). PCR was performed in a 25 μl reaction volume, using 1.25 units of Taq DNA polymerase (Perkin Elmer) and 1 μl of DNA template, in the following conditions: 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 1 μM reverse and forward primers. Thermal cycles were as follows: 94°C for 1 min, (94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min) 34 times and 72°C for 5 min. A second PCR was performed in 50 μl reaction volumes with the same concentrations as above, using 2 μl of the first PCR product as template.

The second PCR product was run on a 1% agarose gel. Amplified DNA was then purified using ‘Quiaquick Gel Extraction Kit’ (Quiagen). Automatic sequencing was done using the ABI Prism BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction (Applied Biosystems). Each sequence was obtained twice with each primer, making a total of four sequences obtained indepen-dently from one DNA extract, from which a consensus was derived. Each base from the final consensus sequence was present in at least three out of the four sequences for every site. Alignment of our sequences with databank sequences was performed using CLUSTALW.

Mitochondrial haplotype determination

Mitochondrial haplotypes (siI, siII or siIII) were determined by restriction fragment length polymorphism. DNA was extracted as in Baba-Aïssa et al (1988) and digested with restriction enzymes Hpa I and Acc I, allowing a double-checking of the haplotypes. siI, siII and siIII were distinguished using restriction maps from Baba-Aïssa et al (1988).

Results

Prevalence and CI assays

The prevalence and CI phenotype in the East African population (Kilimanjaro, Tanzania) are known from a previous study (Merçot and Poinsot, 1998a): 9 lines out of 49 were found infected (prevalence 18.4%) and the Wolbachia variant present in this population, baptized wKi, does not induce CI but is capable of rescuing the CI induced by wNo.

Isofemale lines from the West African population (Yaounde, Cameroon) were screened by PCR for the presence of Wolbachia. Six out of 19 were found to be infected (prevalence: 32%). The CI assays described below were performed using these infected lines.

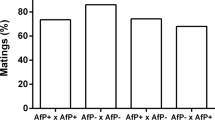

In order to detect the possible expression of CI in Yaounde lines (mod test), males from five infected and five uninfected isofemale lines were individually crossed with two types of uninfected females: from an uninfected reference strain (SimO) and from a pool of Yaounde uninfected lines (massY−). The results, presented in Figure 2a, were analysed using a nonparametrical Wilcoxon test. As presented in Table 1A A, no expression of CI was detected: with both SimO and massY− females, infected males are not significantly less fertile than uninfected ones.

Results of crosses realized with the Yaounde population. A total of 15 replicates were obtained for each category of cross. (a) mod test, involving Yaounde males, infected (grey) and uninfected (white); (b) resc test, involving Yaounde females, infected (grey) and uninfected (white); (c) fertility test, involving Yaounde females, infected (grey) and uninfected (white).

In order to determine if the Wolbachia present in Yaounde was able to rescue the CI induced by other strains (resc test), females from five infected and five uninfected isofemale lines from Yaounde were crossed with males infected by each of the three CI-inducing Wolbachia variants naturally infecting D. simulans (wRi, wHa and wNo) and with males from the ME29 line (a D. simulans line transinfected with wMel, the Wolbachia naturally infecting D. melanogaster; Poinsot et al, 1998). The results, shown in Figure 2b, were analysed using a Wilcoxon test. As presented in Table 1B, no rescue was detected: with all types of males (infected by wRi, wHa, wNo or wMel), infected females are not significantly more fertile than un-infected ones.

We finally tested whether the presence of Wolbachia in the Yaounde population affected female fertility. Females from the massY− (uninfected) and massy+ (infected) were crossed with uninfected and infected males. The results, presented in Figure 2c, were analysed using a Wilcoxon test. As shown in Table 1C, no effect on fertility was detected: with both infected and uninfected males, infected females are not significantly more or less fertile than uninfected ones.

wsp sequences

wsp gene sequences were determined from two West African lines (Y6 and Y12), one East African line (KC9, infected by wKi), as well as in ME29 (infected by wMel) and Coffs Harbour S20 (infected by wAu).

The sequence length was 598 bp for Y6, Y12, Coffs Harbour S20 and ME29. The Coffs Harbour S20 sequence was, as expected, identical to the one obtained by Zhou et al (1998) using the same line (GenBank AF020067). The Y6 and Y12 sequences (GenBank AF290890) were identical to the Coffs Harbour S20 sequence. The ME29 sequence (GenBank AF290891) was identical to some of the previously determined wsp sequences obtained from D. melanogaster by Zhou et al (1998) (GenBank AF020063, AF020064, AF020065, AF020072). The Y6, Y12 and Coffs Harbour S20 sequences differed by five substitutions from the ME29 sequence.

The sequence length was 566 bp for KC9. The KC9 sequence (GenBank AF290889) was identical to the wNo and wMau sequences previously obtained by Zhou et al (1998) (GenBank AF020074 and AF020069). Let us note here that the AF020069 sequence (Zhou et al, 1998) was obtained using a D. simulans line artificially infected by wMau (Giordano et al, 1995), the Wolbachia strain naturally infecting D. mauritiana. Since wMau and wMa are closely related (Rousset and Solignac, 1995, Zhou et al (1998) term this strain wMa.

Mitochondrial haplotypes

Mitochondrial haplotypes were determined in four West African isofemale lines (Y6 and Y12, infected; Y4 and Y5, uninfected), in four East African isofemale lines (K45, KC9, K39, originally infected; K60, originally uninfected), in one East African mass strain (K10P, originally uninfected), as well as in Coffs Harbour S20 and SimO (siII references) and STC (siI reference).

As expected from previous typing (Montchamp-Moreau et al, 1991; James and Ballard, 2000), we found that SimO, Coffs Harbour S20 and STC harboured, respectively, siII, siII and siI. West African lines harboured siII, regardless of their original infection status. East African isofemale lines harboured siIII, regardless of their original infection status. The East African mass strain, originally uninfected, was heterogeneous, harbouring siIII as well as siII cytoplasms.

Discussion

siIII mitochondrial haplotype occurs in continental populations

The three distinct mitochondrial haplotypes of D. simulans show a very strong geographic structuration, on the basis of which biogeographical inferences have been made (Lachaise et al, 1988). The classical view is that (i) siI is restricted to the Seychelles archipelago and Indo-Pacific islands, (ii) siII is much more widely distributed, occurring in all continental populations, as well as in Madagascar and La Reunion islands, and (iii) siIII is restricted to Madagascar and La Reunion islands (Solignac and Monnerot, 1986; Baba-Aïssa et al, 1988; Montchamp-Moreau et al, 1991; Ballard, 2000b).

We have determined the mitochondrial haplotype of several lines from the Kilimanjaro population (Tanzania). The four isofemale lines were found to harbour the siIII haplotype, while a pool from the same area was found to be polymorphic, with siII and siIII cytoplasms. This is not the first report that the siII and siIII cytoplasms can be found in sympatry: this situation occurs in Madagascar and La Reunion (Baba-Aïssa et al, 1988; Ballard, 2000b). However, the siIII haplotype had never been observed in continental populations. This finding suggests that, at least at the mitochondrial level, continental and insular populations are not differentiated. Consistent with our finding are some recent results based on the vermillion locus suggesting that continental and island populations from East Africa are also similar at the nuclear level (N. Derome, personal communication). A more systematic screening of mitochondrial haplotypes in continental East African populations could show whether the pattern we report here reflects a very general or only localized situation. Let us finally mention here that in an earlier paper (Nigro, 1994), the SimO strain (Nasr'allah, Tunisia) was mistakenly reported to harbour the siIII mitochondrial variant (instead of siII), owing to an unfortunate confusion between strain names.

wKi and wNo are closely related, but might not derive from a unique infection event

The [mod− resc+] phenotype, where Wolbachia does not induce CI but is capable of rescuing it, was initially described in the Kilimanjaro population (Merçot and Poinsot, 1998a; Poinsot and Merçot, 1999) using the lines investigated in the present study. The Wolbachia strain responsible for this phenotype was baptized wKi. In these studies, it was shown that wKi, when present in males, does not induce CI, but, when present in females, rescues the embryonic mortality induced by wNo, a relationship that was confirmed in additional experiments (Charlat et al, 2002). The authors thus characterized wKi through CI assays, the results of which suggested that wKi and wNo might be closely related. However, neither the precise phylogenetic position of wKi nor the mitochondrial haplotype associated with this infection were determined. Our sequence results show that wKi and wNo bear the same wsp sequence. Thus, as expected from their CI relationships, and provided that recombination is not misleading us (Werren and Bartos, 2001; Jiggins et al, 2001; Charlat and Merçot, 2001), these two Wolbachia strains are very closely related.

We found that all the infected (or originally infected) lines from Kilimanjaro harbour the siIII mitochondrial haplotype. As mentioned above, such a result was unexpected based on the geographical origin of this strain. It was also unexpected on the basis of the molecular resemblance between wNo and wKi: since wNo is associated with the siI mitochondrial haplotype, a reasonable prediction was that the same would be true for wKi. The hypothesis that wKi and wNo could derive from a unique infection event, having occurred within the siI lineage, is ruled out.

Based on our results, could wNo and wKi result from a divergence associated with the siI/siIII split? In other words, could these two bacterial variants derive from a unique and ancestral infection event, having occurred prior to the coalescence between the three mitochondrial haplotypes? Under such a view, the wNo/wKi strain would have been subsequently lost from the siII lineage, since the siII and siIII haplotypes form together a monophyletic group (Figure 1). We think this scenario is somewhat unlikely. Indeed, wNo and wKi are very closely related: identical wsp sequences and one substitution over 800 bp on the 16S rRNA sequence (A James and J Ballard, personal communication). By contrast, the siI and siIII haplotype are significantly divergent: 355 nucleotide substitutions over 14 959 bp (2.4% divergence) (Ballard, 2000a). In Drosophila, mitochondria seem to evolve at a faster rate than nuclear genes (Moriyama and Powell, 1997), but it has also been suggested that endocellular bacteria have increased substitution rates (Clark et al, 1999). The discrepancy between Wolbachia and mitochondrial divergence would thus make more likely the hypothesis of a recent horizontal transfer. This interpretation must however be considered cautiously, as it does not rely on well-calibrated molecular clocks.

Theory suggests that nothing opposes the decrease of CI intensity within a population of CI-inducing Wolbachia. Indeed, although CI allows Wolbachia to invade host populations, any mutant clone inducing a lower CI, or no CI at all, would not be selected against, as long as the resc function is maintained (Prout, 1994; Turelli, 1994; Hurst and McVean, 1996). Accordingly, it has been suggested that non-CI-inducing Wolbachia could derive from CI-inducing ones. The fact that wNo and wKi are so closely related suggests that a shift between the [mod+] and [mod−] phenotypes can occur within a relatively brief period of time.

wKi and wMa represent the same entity

The wMa Wolbachia strain was initially described from Madagascar (Rousset et al, 1992) as a non-CI-inducing strain (Rousset and Solignac, 1995). Based on 16S rRNA sequences, a slowly evolving marker, these authors showed that wMa and wNo are closely related. However, the CI relationships between wMa and wNo were not investigated. In fact, lines singly infected by wNo were not available until this variant was isolated by segregation from doubly infected lines (Merçot et al, 1995).

Let us consider the following list of arguments, strongly suggesting that wKi and wMa represent the same entity. (i) wMa and wKi show identical wsp sequences (Zhou et al, 1998; this study), as well as identical 16S sequences (Rousset et al, 1992; A James and J Ballard, personal communication). (ii) wMa and wKi are both associated with the siIII mitochondrial haplotype (Rousset and Solignac, 1995; James and Ballard, 2000; this study). (iii) wMa and wKi are both non-CI-inducing strains (Rousset and Solignac, 1995; Merçot and Poinsot, 1998a). (iv) On the basis of mitochondrial haplotypes, it is well accepted that a recent introgression took place between D. simulans and D. mauritiana (Solignac and Monnerot, 1986; Ballard, 2000c), allowing the siIII haplotype, together with the wMa Wolbachia strain, to invade D. mauritiana. Accordingly, the Wolbachia strain occurring in D. mauritiana, usually referred to as wMau, is identical to wMa, on the basis of the 16S rRNA (Rousset and Solignac, 1995). Just as wMa, wMau does not induce CI (Giordano et al, 1995; Rousset and Solignac, 1995). However, it appears that wMau, when injected into D. simulans, is able to rescue the CI induced by wNo (Bourtzis et al, 1998). Thus, wMau and wKi show the same CI phenotype, indirectly suggesting that the same could be true for wMa and wKi. Based on these different arguments, we believe that wKi and wMa represent the same entity. Since the wMa name was published first, we recommend referring to wKi as ‘wMa’ in future publications.

wAu is in West Africa

The wAu infection was originally reported in Australia (Hoffmann et al, 1996) and more recently in Madagascar and Florida, USA (James and Ballard, 2000). Its presence is also suspected, although not clearly demonstrated, in Ecuador (Turelli and Hoffmann, 1995). Based on this geographical distribution, the siII mitochondrial haplotype was expected, and indeed observed by James and Ballard (2000). We found the siII haplotype in the Coffs Harbour S20 line, confirming this result.

The Wolbachia strain that we found in populations from Cameroon seems identical to wAu: (i) the two strains harbour the same wsp sequence, (ii) they are both associated with the siII haplotype and (iii) they do not induce CI (Hoffmann et al, 1996), nor are they able to rescue CI from any of the CI-inducing Wolbachia naturally infecting D. simulans (Merçot and Poinsot, 1998b), or wMel, injected from D. melanogaster into D. simulans (Poinsot et al, 1998).

D. simulans non-African populations are thought to result from a recent expansion of the species (Lachaise et al, 1988). In other words, the Yaounde population, where we observed wAu, is probably older than Australian or American populations that have previously been found infected by this variant. Supporting this view are some results based on the vermillion nuclear gene, confirming that flies from the Yaounde population are probably not reintroduced from recently colonized areas (Hamblin and Veuille, 1999). The presence of wAu, a non-CI-inducing strain, in ancient populations – Cameroon (this study), but also Madagascar (James and Ballard, 2000) – is consistent with current views on CI evolution. Indeed, since the [mod−] phenotype is expected to derive from the [mod+] phenotype (Prout, 1994; Turelli, 1994; Hurst and McVean, 1996), [mod−] strains should, in general, be more ancient than [mod+] ones. If, as we suspect, wAu has been present for a long time in D. simulans, this infection should be associated with a high diversity of mitochondrial haplotypes, unless recent selective sweeps occurred. A study including wAu-infected flies from Madagascar does not support this prediction: mitochondrial genomes associated with wAu cluster together in a narrow monophyletic group (Ballard, 2000b). Including flies from Australia, America and West Africa in such an analysis might clarify this issue.

Non-CI-inducing Wolbachia are widespread in D. simulans

The role played by CI in the spread of Wolbachia has been extensively modelled (reviewed in Hoffmann and Turelli, 1997) and witnessed in real time in the wild (Turelli and Hoffmann, 1995). However, it appears that non-CI-inducing strains can also be maintained in natural populations, as suggested by the widespread occurrence of wAu and wKi/wMa. This apparently paradoxical situation might not be so if the transmission from mothers to offspring is perfect, as observed in Australian populations, in which case Wolbachia infection would simply behave as a neutral variant (Hoffmann et al, 1996). In West African lines, however, it seems that wAu is not perfectly transmitted: uninfected individuals are often collected from initially infected isofemale lines (unpublished results), and the same is true from wKi/wMa. If, as we suspect, transmission is not perfect, other factors, such as positive effects on host fitness, high rates of horizontal transmission, or other reproductive phenotypes, might have to be hypothesized and tested.

References

Baba-Aïssa F, Solignac M, Dennebouy N, David JR (1988). Mitochondrial DNA variability in Drosophila simulans: quasi absence of polymorphism within each of the three cytoplasmic races. Heredity 61: 419–426.

Ballard JWO (2000a). Comparative genomics of mitochondrial DNA in members of the Drosophila melanogaster subgroup. J Mol Evol 51: 48–63.

Ballard JWO (2000b). Comparative genomics of mitochondrial DNA in Drosophila simulans. J Mol Evol 51: 64–75.

Ballard JWO (2000c). When one is not enough: introgression of mitochondrial DNA in Drosophila. Mol Biol Evol 17: 1126–1130.

Bourtzis K, Dobson SL, Braig HR, O'Neill SL (1998). Rescuing Wolbachia have been overlooked. Nature 391: 852–853.

Braig HR, Zhou W, Dobson SL, O'Neill SL (1998). Cloning and characterization of a gene encoding the major surface protein of the bacterial endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. J Bacteriol 180: 2373–2378.

Callaini G, Dallai R, Ripardelli MG. (1997). Wolbachia induced delay of paternal chromatin condensation does not prevent maternal chromosomes from entering anaphase in incompatible crosses in Drosophila simulans. J Cell Biol 110: 271–280.

Callaini G, Riparbelli MG, Giordano R, Dallai R (1996). Mitotic defects associated with cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila simulans. J Invertebr Pathol 67: 55–64.

Charlat S, Bourtzis K, Merçot H (2001). Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility. In: Seckbach J (ed) Symbiosis: Mechanisms and Model Systems, Kluwer Academic Publisher: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 621–644.

Charlat S, Merçot H (2001). Wolbachia and recombination. Trends Genet 17: 493.

Charlat S, Nirgianaki A, Bourtzis K, Merçot H (2002). Evolution of Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila simulans and D. Sechellia. Evolution 56: 1735–1742.

Clark MA, Moran NA, Baumann P (1999). Sequence evolution in bacterial endosymbionts having extreme base composition. Mol Biol Evol 16: 1586–1598.

David J (1962). A new medium for rearing Drosophila in axenic conditions. Dros Inf Ser 93: 28.

Giordano R, O'Neill SL, Robertson HM (1995). Wolbachia infections and the expression of cytoplasmic incompatibi- lity in Drosophila sechellia and D. mauritiana. Genetics 140: 1307–1317.

Hale LR, Hoffmann AA (1990). Mitochondrial DNA polymorphism and cytoplasmic incompatibility in natural populations of Drosophila simulans. Evolution 44: 1383–1386.

Hamblin MT, Veuille M (1999). Population structure among African and derived populations of Drosophila simulans: evidence for ancient subdivision and recent admixture. Genetics 153: 305–317.

Hoffmann AA, Clancy DJ, Ducan J (1996). Naturally-occurring Wolbachia infection that does not cause cytoplasmic incompatibility. Heredity 76: 1–8.

Hoffmann AA, Turelli M (1997). Cytoplasmic incompatibility in insects. In: O'Neill SL, Hoffmann AA, Werren JH (eds) Influential Passengers: Inherited Microorganisms and Arthropod Reproduction, Oxford University Press: Oxford. pp 42–80.

Hoffmann AA, Turelli M, Simmons GM (1986). Unidirectional incompatibility between populations of Drosophila simulans. Evolution 40: 692–701.

Hurst GDD Jiggins FM Schulenburg JH Bertrand D West SA Goriacheva II, et al (1999). Male-killing Wolbachia in two species of insect. Proc R Soc London Ser B 266: 735–740.

Hurst LD, McVean GT (1996). Clade selection, reversible evolution and the persistence of selfish elements: the evolutionary dynamics of cytoplasmic incompatibility. Proc R Soc London Ser B 263: 97–104.

James AC, Ballard JWO (2000). Expression of cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila simulans and its impact on infection frequencies and distribution of Wolbachia pipientis. Evolution 54: 1661–1672.

Jiggins FM, von der Schulenburg JH, Hurst GD, Majerus ME (2001). Recombination confounds interpretations of Wolbachia evolution. Proc R Soc London Ser B 268: 1423–1427.

Lachaise D, Cariou M-L, David JR, Lemeunier F, Tsacas L, Ashburner M (1988). Historical biogeography of the Drosophila melanogaster species subgroup. Evol Biol 22: 159–225.

Lassy CW, Karr TL (1996). Cytological analysis of fertilisation and early embryonic development in incompatible crosses of Drosophila simulans. Mech Dev 57: 47–58.

Merçot H, Charlat S (2003). Wolbachia infections in Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans: polymorphism and levels of cytoplasmic incompatibility. Genetica, in press.

Merçot H, Llorente B, Jacques M, Atlan A, Montchamp-Moreau C (1995). Variability within the Seychelles cytoplasmic incompatibility system in Drosophila simulans. Genetics 141: 1015–1023.

Merçot H, Poinsot D (1998a). Rescuing Wolbachia have been overlooked and discovered on Mount Kilimandjaro. Nature 391: 853.

Merçot H, Poinsot D (1998b). Wolbachia transmission in a naturally bi-infected Drosophila simulans strain from New-Caledonia. Entomol Exp Appl 86: 97–103.

Montchamp-Moreau C, Ferveur J-F, Jacques M (1991). Geographic distribution and inheritance if three cytoplasmic incompatibility types in Drosophila simulans. Genetics 129: 399–407.

Moriyama EN, Powell JR (1997). Synonymous substitution rates in Drosophila: mitochondrial versus nuclear genes. J Mol Evol 45: 378–391.

Nigro L (1994). Nuclear background affects frequency dynamics of mitochondrial DNA variants in Drosophila simulans. Heredity 72: 582–586.

O'Neill SL, Giordano R, Colbert AME, Karr TL, Robertson HM (1992). 16S rRNA phylogenetic analysis of the endosymbionts associated with cytoplasmic incompatibility in insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 2699–2702.

O'Neill SL, Karr TL (1990). Bidirectional incompatibility between conspecific populations of Drosophila simulans. Nature 348: 178–180.

Poinsot D, Bourtzis K, Markakis G, Savakis C, Merçot H (1998). Wolbachia transfer from Drosophila melanogaster into D. simulans: host effect and cytoplasmic incompatibility relationships. Genetics 150: 227–237.

Poinsot D, Merçot H (1997). Wolbachia infection in Drosophila simulans: does female host bear a physiological cost? Evolution 51: 180–186.

Poinsot D, Merçot H (1999). Wolbachia can rescue from cytoplasmic incompatibility while being unable to induce it. In: Wagner E et al (eds) From Symbiosis to Eukaryotism – Endocytobiology VII, University of Geneva Freiburg: Breisgau. pp 221–234.

Poinsot D, Montchamp-Moreau C, Merçot H (2000). Wolbachia segregation rate in Drosophila simulans naturally bi-infected cytoplasmic lineages. Heredity 85: 191–198.

Presgraves DC (2000). A genetic test of the mechanism of Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila. Genetics 154: 771–776.

Prout T (1994). Some evolutionary possibilities for a microbe that causes cytoplasmic incompatibility in its host. Evolution 48: 909–911.

Reed KM, Werren JH (1995). Induction of paternal genome loss by the paternal-sex-ratio chromosome and cytoplasmic incompatibility bacteria Wolbachia: a comparative study of early embryonic events. Mol Reprod Dev 40: 408–418.

Rigaud T (1997). Inherited microorganisms and sex determination of arthropod hosts. In: Hoffmann SL, Werren JH (eds) Influential Passengers: Inherited Microorganisms and Arthropod Reproduction, Oxford University Press: Oxford. pp 81–108.

Rousset F, Solignac M (1995). Evolution of single and double Wolbachia symbioses during speciation in the Drosophila simulans complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 6389–6393.

Rousset F, Vautrin D, Solignac M (1992). Wolbachia endosymbionts responsible for various alterations of sexuality in arthropods. Proc R Soc London Ser B 247: 163–168.

Satta Y, Takahata N (1990). Evolution of Drosophila mitochondrial DNA and the history of the melanogaster subgroup. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 9558–9562.

Solignac M, Monnerot M (1986). Race formation, speciation, and introgression within Drosophila simulans, D. mauritiana, and D. sechellia inferred from mitochondrial DNA analysis. Evolution 40: 531–539.

Stevens L, Giordano R, Fialho RF (2001). Male-killing, nematode infections, bacteriophage infection, and virulence of cytoplasmic bacteria in the genus Wolbachia. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 32: 519–545.

Stouthamer R (1997). Wolbachia-induced parthenogenesis. In: Hoffmann SL, Werren JH (eds) Influential Passengers: Inherited Microorganisms and Arthropod Reproduction, Oxford University Press: Oxford. pp 102–124.

Stouthamer R, Breeuwer JAJ, Hurst GDD (1999). Wolbachia pipientis: microbial manipulator of arthropod reproduction. Annu Rev Microbiol 53: 71–102.

Turelli M (1994). Evolution of incompatibility-inducing microbes and their hosts. Evolution 48: 1500–1513.

Turelli M, Hoffmann AA (1995). Cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila simulans: dynamics and parameter estimates from natural populations. Genetics 140: 1319–1338.

Werren JH (1997). Biology of Wolbachia. Annu Rev Entomol 42: 587–609.

Werren JH, Bartos JD (2001). Recombination in Wolbachia. Curr Biol 20: 431–435.

Zhou W, Rousset F, O'Neill SL (1998). Phylogeny and PCR-based classification of Wolbachia strains using wsp gene sequences. Proc R Soc London Ser B 265: 509–515.

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to Laurent Marin. We thank Frédérique Machetto, Mélanie Baril and Catherine Dubuc for their contributions to the experiments, and Valerie Delmarre and Chantal Labellie for technical assistance. We are most grateful to Avis James and Bill Ballard for providing the wKi 16S rRNA sequence, to Michel Solignac for his help on mitochondrial typing, and to Bill Ballard, Kostas Bourtzis, Denis Poinsot and Markus Riegler for helpful comments on this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Charlat, S., Le Chat, L. & Merçot, H. Characterization of non-cytoplasmic incompatibility inducing Wolbachia in two continental African populations of Drosophila simulans. Heredity 90, 49–55 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6800177

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6800177

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Evolution of reproductive parasites with direct fitness benefits

Heredity (2018)

-

Inter-population variation for Wolbachia induced reproductive incompatibility in the haplodiploid mite Tetranychus urticae

Experimental and Applied Acarology (2015)

-

Comparative genome analysis of Wolbachia strain wAu

BMC Genomics (2014)

-

Host genotype changes bidirectional to unidirectional cytoplasmic incompatibility in Nasonia longicornis

Heredity (2012)

-

Wolbachia infections that reduce immature insect survival: Predicted impacts on population replacement

BMC Evolutionary Biology (2011)