Key Points

- Esophageal diverticula can be categorized as (1) true diverticula that contain all the layers of the esophageal wall, (2) false diverticula that contain only the mucosa, and (3) intramural diverticula in which the mucosa outpouching occurs within the wall.

- The diverticula may result from outpouching of the weakness in the wall associated with increased intraluminal pressure or traction from fibrosis in the mediastinum.

- Zenker's diverticulum is a common, false, pharyngeal diverticulum that arises above the cricopharyngeus muscle.

- Mid-esophageal diverticulum may be associated with diffuse esophageal spasm or mediastinal fibrosis.

- Epiphrenic diverticula are often associated with achalasia.

- Diffuse intramural diverticulosis may occur owing to dilation of the esophageal glands.

- Lower esophageal rings are of two types: (1) mucosal ring (Schatzki's ring, also called B ring), which is located at the squamocolumnar mucosal junction; it is common, and is associated with characteristic history; and (2) muscular ring (A ring), which is located proximal to the mucosal ring; it is uncommon, and is covered by squamous epithelium.

- Esophageal webs are most frequent in the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus and are distinguished by their location anteriorly. Webs may also occur anywhere in the esophagus.

- Rings and webs can be treated by dilation.

Introduction

Anatomic lesions affecting the esophagus are common and can cause dysphagia and acute food impaction. This review addresses three major categories of anatomic lesions: esophageal diverticula, esophageal rings, and webs. The clinical presentations, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of patients with these conditions are discussed.

Pharyngeal and Esophageal Diverticula

Definition, Epidemiology, and Pathophysiology

Diverticula are outpouchings of one or more layers of the intestinal wall that may occur at any level of the esophagus. The number of intestinal wall layers involved distinguishes the true, false, and intramural types of diverticula. True diverticula contain all layers of the intestinal wall, false diverticula contain only mucosal and submucosal layers, and intramural diverticula refer to outpouchings contained within the submucosa layer. The most common pharyngeal diverticula (Zenker's) are false diverticula immediately proximal to the cricopharyngeus muscle.1 Diverticula of the body of the esophagus are divided into midthoracic (parabronchial) and epiphrenic diverticula. These three types of diverticula are illustrated in Figure 1. Another condition, intramural pseudodiverticulosis or diffuse intramural diverticulosis is a rare entity of multiple 1- to 3-mm mucosal outpouchings associated with inflammation and esophageal wall thickening.2, 3 The openings of these small diverticula, however, are often not visible during endoscopic examination, and are typically seen only on barium swallow.

Figure 1: Illustration and radiological appearance of Zenker's mid esophageal and epiphrenic esophageal diverticula.

(Source: Netter image, with permission from Elsevier. All rights reserved.)

Epidemiologic data of esophageal diverticula are sparse. In patients undergoing radiologic evaluations for dysphagia, Zenker's diverticulum was found in 2.3%.4 The prevalence of Zenker's diverticula among the general population is believed to be between 0.01% and 0.11%,5 with the majority of patients diagnosed being older than 70 years of age. The prevalence of midthoracic and epiphrenic diverticula in the general population is unknown, although these are significantly less common than Zenker's diverticula. The different types of pharyngeal and esophageal diverticula are summarized in Table 1.

The pathophysiology of Zenker's diverticula has been carefully studied using a combination of simultaneous video-swallow and manometry.6 There is a reduced upper esophageal sphincter opening as a consequence of fibroadipose tissue replacement of the cricopharyngeus muscle causing diminished upper esophageal sphincter compliance.7 This constrictive myopathy is responsible for an increase in pharyngeal and hypopharyngeal intra-bolus pressures during swallowing. As a result, there is herniation through areas of potential weakness in the posterior pharyngeal wall, especially Killian's triangle.

Traction diverticula are traditionally believed to be caused by fibrosis secondary to inflammation of the mediastinum,4 as can occur with fungal infections or tuberculosis. But studies have demonstrated that mid-esophageal diverticula can also be associated with esophageal motility abnormalities, most notably achalasia and diffuse esophageal spasm.8

Pulsion diverticula are mucosal outpouchings resulting from long-standing esophageal luminal obstruction of either anatomic (strictures) or functional nature.9, 10 The majority of pulsion diverticula are associated with diffuse esophageal spasm or achalasia.11, 12

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Most patients with Zenker's diverticula are diagnosed in the sixth to eighth decades of life.5 Their symptoms may range from globus sensation (the sensation of a lump or foreign body in the cervical esophagus) to complete esophageal obstruction. Oropharyngeal dysphagia with regurgitation is the classic presenting complaint and can occur regardless of the size of the diverticulum. This is owing to the fact that the openings of Zenker's diverticula are often aligned facing the axis of the pharynx so that the food particles preferentially enter into the diverticulum, potentially causing compression of the adjacent esophageal lumen. Aspiration pneumonia, halitosis, and gurgling in the throat may also be present. In advanced disease, appearance of a mass in the neck, hoarseness, and weight loss can occur. The most common complication for Zenker's diverticula is aspiration pneumonia, but other complications such as bleeding and perforation can also develop in these patients.

Midthoracic and epiphrenic diverticula are usually asymptomatic, discovered during routine radiologic evaluations for unrelated complaints. Symptoms of dysphagia and regurgitation can be reported by patients, particularly those with diverticula related to diffuse esophageal spasm or achalasia. Complications of midthoracic and epiphrenic diverticula are often owing to underlying esophageal motility disorders and include esophageal obstruction, bezoar formation, and cardiac dysrhythmia. Finally, a rare but serious complication for pharyngeal or esophageal diverticula is the development of carcinoma within the pouch.

Diagnostic modalities for pharyngeal and esophageal diverticula include barium swallow, upper endoscopy, esophageal manometry, and computed tomography scan, or any combination of the above. Computed tomography scan can be especially helpful in the evaluation of traction diverticulum by providing definitions of the adjacent anatomic structures in the mediastinum. The differential diagnosis for oropharyngeal dysphagia includes iatrogenic causes such as tracheostomy, neck surgery, laryngectomy, and malignancy.

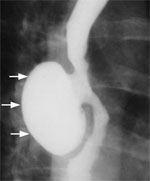

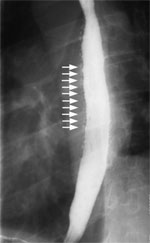

The barium swallow is a very helpful examination in the diagnosis of each of the diverticular conditions. A Zenker's diverticulum is a pharyngeal outpouching readily seen in the cervical region (Figure 2). A midthoracic or traction diverticulum is typically a small, wide-mouth pouch located near the tracheal bifurcation (Figure 3). An epiphrenic diverticulum, on the other hand, appears as a large globular pouch, often associated with abnormal esophageal contractions, as demonstrated in Figure 4. Intramural pseudodiverticulosis has an inconsistent appearance on barium imaging, but with repeated swallows numerous small outpouchings are seen along the wall of the esophagus (Figure 4).

Figure 2: Barium swallow of a patient with Zenker's diverticulum.

Arrows point to the pharyngeal pouch. (Source: Courtesy of John M. Braver, Brigham and Women's Hospital.)

Figure 3: Barium swallow of a patient with midthoracic or traction diverticulum.

Arrows point to the small, wide mouth pouch located at the tracheal bifurcation. (Source: Courtesy of John M. Braver, Brigham and Women's Hospital.)

Figure 4: Barium swallow of a patient with intramural pseudodiverticulosis.

Arrows point to the numerous small outpouchings along the wall of the esophagus. (Source: Courtesy of John M. Braver, Brigham and Women's Hospital.)

Visual inspection of the esophagus with esophagoscopy can also yield important information about the diverticulum, particularly in ruling out underlying cancer within the diverticulum. However, gentle insertion of the instrument is critical, particularly for pharyngeal diverticulum, as the blind pouch can be mistaken for esophageal lumen. This can result in perforation. An example of the endoscopic appearance of Zenker's diverticulum is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Endoscopic appearance of Zenker's diverticulum.

(Source: Courtesy of David L. Carr-Locke, Brigham and Women's Hospital.)

Esophageal manometry can reveal esophageal motor disorders that may be the underlying cause of the formation of diverticula. In addition, manometric study may also facilitate the planning of surgical correction.

Treatment and Outcome

Although small asymptomatic Zenker's diverticula can be followed clinically, symptomatic Zenker's diverticula should be treated. For small diverticula, cricopharyngeal myotomy alone is sufficient. Larger diverticula can be treated with diverticulum suspension or diverticulectomy along with cricopharyngeal myotomy. For patients with a Zenker's diverticulum and concomitant gastroesophageal reflux disease, a combined diverticular and antireflux surgery should be considered to prevent the potential of severe regurgitation and aspiration after surgery. Therapeutic outcomes for cricopharyngeal myotomy are excellent, with symptom control achieved in 78% of patients.13 The recurrence rate for Zenker's is between 3.6% and 4.8% after myotomy.13, 14 Various endoscopic techniques to cut the common wall or stapling together of the walls between the diverticulum and the esophagus have been reported.15, 16, 17, 18 Postendoscopic resection of the diverticulum is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Postendoscopic resection appearance of the Zenker's diverticulum.

(Source: Courtesy of David L. Carr-Locke, Brigham and Women's Hospital.)

Midthoracic or epiphrenic diverticula that are asymptomatic need not be treated. In symptomatic patients, treatment should be aimed at the underlying esophageal motility disorder or stricture. Surgical management of midthoracic or epiphrenic diverticula can involve extended myotomy and diverticulectomy with an antireflux procedure. The surgical mortality has been reported to be 9% for epiphrenic diverticula.19 The goal of surgical therapy here is to address the underlying esophageal motor disorder, which is typically spastic in nature, and keep the lumen wide open so that the food can pass through the conduit into the stomach.

Esophageal Rings

Definition, Epidemiology, and Pathophysiology

Distal esophageal rings are frequent findings on barium contrast x-ray studies. If the ring occurs right at the squamocolumnar junction, it is known as a B ring and is lined with squamous epithelium above and columnar epithelium below. Alternatively the ring may be muscular in appearance, positioned at the upper aspect of the phrenic ampulla corresponding to the highest pressure zone of the lower esophageal sphincter, and known as an A ring. (Figure 7). Symptomatic A rings are uncommon and characterized by smooth muscle cell hypertrophy in the body of the esophagus.20 The hypertrophied muscle can measure up to 4 to 5 mm in thickness, and the muscle is covered with normal epithelium. B rings or lower esophageal mucosal rings are fixed, reproducible structures on barium studies, and are asymptomatic when the luminal diameter is greater than 20 mm. A lower esophageal mucosal ring is pathologic when the luminal narrowing is accompanied by dysphagia, which is often referred to as Schatzki's ring.21

Figure 7: Illustration of A ring (muscular ring) and B ring (Schatzki mucosal ring) in the lower esophagus.

(Source: Netter image, with permission from Elsevier. All rights reserved.)

Lower esophageal mucosal rings are found in 6% to 14% of subjects undergoing routine barium swallow studies,22 which are considered to be normal structures. However, in 0.5% of patients with the narrowed lumen and dysphagia, these rings are pathologic.23 Schatzki's ring is the cause in up to 26% of patients with esophageal dysphagia.

The etiology of pathologic mucosal and muscular esophageal rings are unknown. Schatzki's rings have been proposed to be related to gastroesophageal reflux disease, but there is no consensus on this.24, 25, 26 Schatzki's ring appears to be associated with a decreased incidence of Barrett's esophagus,27 although it does not seem to protect against reflux.28 Eosinophilic esophagitis is a condition with a reported association with Schatzki's rings,29 particularly in the pediatric population,30, 31

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Symptoms associated with Schatzki's rings are related to the residual luminal diameter. Most patients with less than 13 mm of luminal diameter report symptoms of dysphagia.32 Dysphagia is mostly to solid food and is often chronic and intermittent in nature. Esophageal rings are common causes of acute solid food impaction; often pieces of meat become impacted in the nondistensible ring. Patients with a wider Schatzki's ring can have associated symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease such as heartburn or regurgitation symptoms.

Long-term follow-up of patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic esophageal rings has shown that the lower esophageal mucosal ring diameter diminished slowly over time32, 33 and the ring diameter is the major determinant for the onset of clinical symptoms. Complications of pathologic esophageal rings most commonly result from acute food impaction and treatment thereof. Therefore, perforation, bleeding, and aspiration pneumonia are all potential complications, but rarely reported.34

Barium swallow with full column technique has the highest reported detection rate for Schatzki's rings.35 This technique involves placing the patient in the prone right anterior oblique position, and the Valsalva maneuver distends the lower esophageal segment as the patient is swallowing the barium. This method detects almost all of the esophageal rings compared to detection rates of only 17% to 49% with conventional double-contrast techniques. A marshmallow or barium tablet can also be used during the barium swallow to facilitate the visualization of the ring.36 The radiologic appearance of a mucosal and a muscular ring is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Barium swallow of a patient with A and B rings of the distal esophagus.

Large arrow points to the B ring, and the small arrow points to the A ring.

Upper endoscopy is another diagnostic modality for the detection of Schatzki's rings. However, the sensitivity of endoscopy for detecting esophageal rings may be less than that of barium swallow owing to the reduced esophageal distention that can be achieved during upper endoscopy. However, esophageal rings that have narrowed the esophageal lumen significantly to less than 13 mm can be easily detected using endoscopy.

Esophageal manometry and ambulatory acid exposure studies can be helpful in detecting associated esophageal motor abnormalities and gastroesophageal reflux disease. High-amplitude, long-duration, but peristaltic contractions with multiple peaks have been reported with muscular rings.21

Other laboratory investigations can be tailored to the individual patient, for example, complete blood count in patients with suspected eosinophilic esophagitis to determine the presence of peripheral eosinophilia. Differential diagnosis for esophageal rings includes esophageal webs, eosinophilic esophagitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, as well as benign and malignant tumors of the esophagus, which can all cause intermittent solid food dysphagia.

Treatment and Outcome

Treatment of pathologic A and B rings is mechanical dilation. This can be performed using either a single, large, mercury-weighted tip dilator (bougie or Maloney dilator), or a series of incrementally larger diameter dilators over a guidewire (Savary dilators) or through the scope balloon dilators.37, 38 The dilation procedure can be performed with the patient under conscious sedation. The patient is usually kept on an overnight fast to prevent aspiration. Antiplatelet agents or anticoagulation agents are usually discontinued for 5 days prior to the dilation. For those patients at high risk of bacterial endocarditis, antibiotic prophylactics should be given. For pathologic muscular rings, injection of botulinum toxin have been reported to have some efficacy.39, 40

The main limitation of bougie dilation is the high rate of recurrence after treatment. After a single dilatation, 68% of patients with Schatzki's rings are symptom free at 1 year, 35% patients remain symptom free after 2 years, and only 11% are symptom free at 3 years.37 For patients with symptomatic recurrence, dilation can be performed repeatedly without serious complications. For recurring lower esophageal ring, endoscopic incision of the ring is an alternative treatment option.41, 42, 43 For patients who cannot achieve acceptable symptom resolution without frequent dilation, self-dilation using a Maloney dilator is another therapeutic option.

For Schatzki's rings associated with other conditions such as eosinophilic esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease, treatment should be directed at the underlying disease after the ring has been disrupted. Acid suppression with proton pump inhibitor for acid reflux disease and topical steroids for eosinophilic esophagitis should be the mainstay of therapy for these patients.

Esophageal Webs

Definition, Epidemiology, and Pathophysiology

An esophageal web is a thin, membranous tissue covered with squamous epithelium that compromises the lumen of the esophagus. Esophageal webs are divided into congenital and acquired webs. Congenital webs usually occur in the middle and lower thirds of the esophagus, and are more likely to be circumferential with a central or eccentric orifice. Acquired webs are typically thin and translucent, much more common than congenital webs, and are often located anteriorly in the cervical esophagus in the postcricoid region.

Congenital webs are very rare with a total of 20 cases reported in the literature from 1922 to 1975. The exact prevalence of acquired webs is unknown because the majority of patients are asymptomatic. In patients undergoing barium swallow studies, 5.5% to 8% were found to have cervical webs.44, 45

Congenital webs result from failure of coalescence of esophageal vacuoles, which lead to complete luminal patency that occurs between days 25 and 31 of embryologic development.46 The etiologies of acquired esophageal webs are complex. Esophageal webs that are associated with iron-deficiency anemia, glossitis, koilonychia, and esophageal or pharyngeal carcinoma are known as Plummer-Vinson syndrome in North America and Paterson-Kelly syndrome in the United Kingdom. Esophageal webs have also be reported to be associated with extracutaneous manifestations of bullous dermatologic disorders such as epidermolysis bullosa,47 bullous pemphigoid,48 pemphigus vulgaris,49 desquamative esophagitis in chronic graft-versus-host disease,50 as well as gastroesophageal reflux disease.51

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

The principal presenting symptom for patients with webs is dysphagia. In patients with congenital webs, dysphagia can start in the neonatal or early childhood years. The severity of the dysphagia is directly related to the degree of luminal obstruction. Acquired esophageal webs are twice as common in women than in men.52 Patients can present with nasopharyngeal reflux, aspiration, and spontaneous perforation.53 The other presenting complaint for patients with esophageal webs is acute solid food impaction.

Physical findings of esophageal webs are often related to the associated medical conditions. Bullous dermatologic disorders such as epidermolysis bullosa, bullous pemphigoid, and pemphigus vulgaris have classic skin findings on physical examination. Chronic graft-versus-host disease is often associated with skin hyperpigmentation. In patients with Plummer-Vinson syndrome, pale, waxy oropharyngeal mucosal, smooth tongue, and spoon nails are classic findings of iron-deficiency anemia.

Most patients with cervical webs are asymptomatic. However, complications such as perforation, bleeding, and aspiration pneumonia can occur, particularly during acute food impaction.

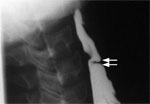

Diagnostic modalities for esophageal webs include barium swallow and upper endoscopy. The barium swallow appearance of a cervical web is shown in Figure 9. The endoscopic instrument must be inserted carefully, because the initial passage of the endoscope may pierce the web before its presence can be appreciated by the endoscopist.

Figure 9: Barium swallow appearance of esophageal web.

The arrows point to the web. (Source: Courtesy of John M. Braver, Brigham and Women's Hospital.)

Esophageal rings should be the main differential diagnosis for patients presenting with dysphagia and suspected esophageal webs. Other structural lesions such as benign and malignant tumors of the esophagus and esophagitis (reflux related, eosinophilic, or infectious) should also be on the list of possible differential diagnosis for these patients.

Treatment and Outcome

For asymptomatic esophageal webs, no treatment is necessary. For patients with mild symptoms, lifestyle modifications such as chewing food carefully, eating slowly, and avoiding certain foods can often eliminate symptoms. Mechanical dilation with a large, mercury-weighted tip dilator, or a series of dilators over a guidewire or a through the scope balloon dilator37, 38 can be used. In patients with underlying medical conditions such as iron-deficiency anemia or chronic graft-versus-host disease, treatment should be aimed at the underlying medical condition after dilatation. Very rarely, surgical treatment is needed for patients with cervical webs.54

Conclusion

Anatomic lesions of the esophagus, such as diverticula, rings, and webs, are common, but most patients are asymptomatic. In patients presenting with dysphagia or solid food impactions, appropriate diagnostic tests should be employed to evaluate the underlying cause.