Abstract

Purpose:

To assess the impact of BRCA1/2 test results on carriers’ reproductive decision-making and the factors determining their theoretical intentions about preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) and prenatal diagnosis (PND).

Methods:

Unaffected BRCA1/2 mutation carriers of childbearing age (N = 605; 449 women; 151 men) were included at least 1 year after the disclosure of their test results in a cross-sectional survey nested in a national cohort. Multivariate adjustment was performed on the data obtained in self-administered questionnaires.

Results:

Response rate was 81.0%. Overall, 32.5% and 50% said that they would undergo PGD/PND, respectively, at a theoretical next pregnancy, whereas only 12.1% found termination of pregnancy (TOP) acceptable. Theoretical intentions toward PGD did not depend on gender/age, but were higher among those with no future childbearing plans (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 95% confidence interval (CI): 3.5 (1.9–6.4)) and those having fewer relatives with cancer (AOR 1.5 95% CI (1.0–2.3)). Greater TOP acceptability was observed among males and those with lower educational levels; 85.4% of respondents agreed that information about PGD/PND should be systematically delivered with the test results.

Conclusions:

The closer to reproductive decision-making BRCA1/2 carriers are, i.e., when they are more likely to be making future reproductive plans, the less frequently they intend to have PGD. Carriers’ theoretical intentions toward PND are discussed further.

Genet Med 2012:14(5):527–534

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer genes involved in hereditary breast/ovarian cancer were identified >15 years ago, and dealing with the reproductive concerns of upcoming generations is a new issue, which needs to be addressed at adult cancer genetic clinics.1,2 The impact of BRCA1/2 germline mutations on people’s reproductive history has not yet been documented, as few unaffected people have been informed so far about their mutation status before completing their family plans. How carriers adapt their family planning to their carrier status is an issue that needs to be addressed in the light of the latest assisted reproduction methods.

The value of preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) for people with an inherited predisposition to cancer has been clearly established, but it has been assumed that both patients and providers distinguish between this method and prenatal diagnosis (PND), although the issue of PND is practically impossible to disentangle from that of PGD, mainly for the technical reasons described elsewhere.2 The acceptability of PND appears to be high in France.3,4 PGD and PND seem to be proposed differently to BRCA1/2 mutation carriers from one country to another.5,6 In France, multidisciplinary PND teams are legally responsible for authorizing individuals to undergo PGD/PND procedures after examining the severity of the genetic risk case by case. Couples who obtain this authorization can benefit from these interventions free of charge as they are paid for by the French health insurance system. However, as we previously reported, many French professionals responsible for authorizing PGD/PND procedures do not readily do so in the case of BRCA1/2 carriers.2 As far as we know, no BRCA1/2 carriers have yet been authorized to have PGD/PND in France.

The attitudes and expectations of BRCA1/2 mutation carriers of reproductive age are key factors that need to be taken into consideration in clinical practice. Several studies (see Supplementary Table S1 online) have been performed on men and women applying for BRCA1/2 tests,6,7,8,9 but very few have focused on unaffected BRCA1/2 carriers of childbearing age. However, in one study on 52 female BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, half of whom had developed cancer, the levels of theoretical acceptability of PGD/PND were found to be low; only 1 out of 7 contemplating a future pregnancy said they would consider having PND/PGD.10 No such study has been carried out on male BRCA1/2 carriers.

The aim of this study was first to assess whether and in what way the BRCA1/2 findings had affected the reproductive decision-making of unaffected carriers of childbearing age. It was also proposed to describe the sociodemographic and other characteristics associated with people’s intentions to have PGD and PND.

In this population, the intended uptake of PGD and PND was expected to be low, but higher in the case of PGD than PND. It was expected to depend not only on gender and other sociodemographic and personal characteristics, but also on the participants’ previous family history.

Materials and Methods

Study group

Participants were selected from the French GENEPSO (GENe Etude Predisposition Sein Ovaire) cohort,11which consists of all BRCA1/2 carriers recruited in the context of routine consultations since 2000; 24 cancer genetic clinics participated.

Eligible subjects were women between the age of 18 and 49 years and men between the age of 18 and 69 years at the time of the survey, who all carried a deleterious BRCA1/2 mutation, had not developed cancer, and had received their test results at least 1 year earlier. The protocol was approved by the “Comité National Informatique et Libertés.”

Data collected

Eligible participants were sent a self-administered questionnaire including 65 questions (five of which were open-ended). The questionnaire focused on how the BRCA test results had affected their childbearing plans, what they felt about possibly having PGD/PND at their next pregnancy, and when information about PGD/PND should be delivered in the context of the French health-care system. It also included questions about their sociodemographic status, their childbearing plans, the perceived cancer risk and health status, and their opinions about termination of pregnancy (TOP).

Dependent variables

Impact of genetic tests on ongoing reproductive plans. Participants were asked whether the BRCA1/2 test results had affected their ongoing parental plans—yes, definitely/yes, somewhat/no, not really/no, not at all/not relevant (because they already had as many offspring as they wanted or were too young to make childbearing plans). Participants giving a positive reply were asked to explain in their own words how their plans had changed.

Theoretical intentions about having PGD or PND. The participants’ theoretical intentions about PGD/PND were measured separately on a five-item Likert scale: “Imagine you want to have a child and PGD/PND is available in France for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Would you want to undergo these interventions?” (yes, certainly/yes, probably/I don’t know/no, not really/no, not at all). The analysis was dichotomized in order to compare those who would certainly/probably want to undergo PGD/PND with the others. These questions were asked after giving one page of information in order to standardize the participants’ basic knowledge about these interventions (Appendix).

Acceptability of TOP. Participants were asked whether they felt TOP was acceptable for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers in general (yes, certainly/yes, fairly/it depends/no, not really/no, certainly not/I don’t know), and then, whether they would have it themselves. TOP was analyzed first as a variable explaining the participants’ intentions to have PGD/PND and second, as a dependent variable.

Delivery of information about PGD/PND. Assuming PGD/PND to be allowed in France and easily available to BRCA1/2 carriers, the respondents were asked to give their opinion as to when this information should be delivered: systematically at disclosure of the test results/only to carriers with childbearing plans, and by whom. Answers were given on a four-item Likert scale (yes, definitely/yes, maybe/no, not really/no, not at all).

Independent variables

The sociodemographic data collected included gender, age, marital status, education and employment status, number of children, and religious beliefs. Future childbearing plans were ascertained via a seven-item closed question ( Table 1 ).

Cancer risk perceptions. The perceived cancer risk was measured by asking the following question: “Compared to other people of your own age and gender, do you feel your risk of developing cancer is (much higher/higher/the same/lower/much lower)?” This item was dichotomized in order to compare those who rated their risk as higher/much higher with the other participants.

Perceived health status. Participants’ own perceived health was assessed by asking the following question: “Compared to other people of your own age and gender, how would you rate your health status?” (excellent/very good/good/fair/poor). This item was dichotomized in order to compare those who rated their health status as excellent/very good with the other participants.

Family history of breast/ovarian cancer, including the number of female first- and second-degree relatives who had developed breast cancer, was collected from the clinical records.

Statistical analysis

Only gender could be compared between respondents and nonrespondents. After a descriptive analysis of the study population, we looked first at whether and how the participants’ childbearing plans had been affected by their BRCA1/2 test results. Two authors (C.P. and C.J.R.) coded the participants’ comments to the open-ended questions separately before reaching a consensus on discrepancies.

We then looked at the factors associated with the participants’ intentions to have PGD/PND if they became pregnant, and those associated with the acceptability of TOP for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. We then focused on the participants who were pregnant, paying special attention to their open comments. Finally, all the respondents’ expectations about the delivery of PGD/PND information were analyzed.

χ2-Tests and Student’s t-tests were performed to compare variables. In the multivariate analyses, logistic regression models were performed to identify the factors independently associated with the outcome variables (entry threshold P < 0.10). All the statistical analyses were performed using the STATA, version 9.0 software program (STATA, College Station, TX).

Results

Description of the study population

Among the unaffected BRCA1/2 carriers surveyed, 81.0% (490 out of the 605) returned the completed questionnaires. No significant differences (P = 0.33) were observed between the response rates of men and women: 78% (118 of the 152) and 82% (372 of the 453), respectively. Because 30 of the respondents were excluded because of missing values in the outcome variables studied, the final sample consisted of 460 individuals. The average number of participants per centre (n = 24) was 11.8 (s.d. = 11.7, range (1–99)). Median time elapsing between BRCA1/2 test result disclosure and the end of the survey was 3.8 years (range (1.1–10.9)). Sociodemographic data and other descriptive data on men and women are presented in Table 1 . Women were younger (37.1 on average) than men (49.8) at the time of the survey and at test result disclosure, and they also differed in other respects because different inclusion criteria were used ( Table 1 ).

Impact of BRCA1/2 test results on respondents’ childbearing plans

Among the respondents, 16.3% (n = 75) stated that the BRCA1/2 test results had affected their ongoing childbearing plans in some way. After multivariate adjustment, these respondents were more frequently women (P = 0.05), were younger (P = 0.003), and had a higher educational level (P = 0.002) than the others. Qualitative details about how their plans had changed are given in Table 2 . The most frequently mentioned consequence (n = 28), was that the respondents’ reproductive plans had accelerated because of the possibility of undergoing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy. The second most frequent qualitative change (n = 21) was the psychological burden due to either feelings of guilt about possibly transmitting the deleterious mutation to the present/future offspring, or the stress resulting from the idea that pregnancy might precipitate their cancer history. The third consequence mentioned (n = 15) was giving up the wish to have more children because of their carrier status: the majority of this group (n = 8) already had two children. Finally, three participants mentioned either having had a PGD because of their BRCA2 carrier status (n = 1) or wanting to benefit from assisted procreation (n = 2). The real reason for the PGD was checked and found to be fragile-X syndrome, however.

Theoretical intentions to undergo PGD, and related factors

Overall, 32.5% (168/460) of the participants said they would undergo PGD if they were considering another pregnancy. After multivariate adjustment, the factors found to be significantly associated with these positive intentions were having no reproductive plans for the future (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 95% confidence interval (CI) 3.5 (1.9–6.4)), feeling TOP to be acceptable for themselves if a BRCA1/2 mutation was detected in the fetus (AOR 95% CI: 3.2 (1.6–6.1)), and to a lesser extent, having fewer cases of breast/ovarian cancer in the family ( Table 3 ). Other factors found to be significant in the univariate comparisons (gender, age, educational level, and perceived health status) were no longer significant after multivariate adjustment ( Table 3 ). The other independent variables tested were not significantly correlated with the respondents’ theoretical intentions about PGD.

Theoretical intentions to undergo PND, and related factors

Overall, 50% of the participants (230/460) said they would undergo PND for a theoretical next pregnancy. After multivariate adjustment, the significance of the gender difference was only borderline (P = 0.057; Table 4 ): the main explanatory variables were a positive attitude toward TOP (AOR 95% CI: 7.7 (3.3–17.9)) and a lower educational level (AOR 95% CI: 1.5 (1.0–2.2); Table 4 ). The other independent variables tested were not significantly correlated with the respondents’ PND intentions; 44% (48/109) of those with future childbearing plans had positive theoretical intentions toward PND compared with 51.8% (182/351) of those without childbearing plans (P = 0.15).

Theoretical acceptability of TOP

Overall, 12.2% (56/460) of the respondents said that they felt TOP would be acceptable if their fetus was found to carry a BRCA1/2 mutation ( Table 5 ). This score was similar to that obtained on the acceptability of TOP for pregnant BRCA1/2 mutation carriers in general ( Table 1 ).

After multivariate adjustment, men found TOP more acceptable than women (AOR 95% CI: 2.3 (1.1–5.1)), as did respondents with a lower educational level (AOR 95% CI: 2.2 (1.2–4.1)). Participants who declared that the BRCA1/2 test results had affected their childbearing plans also found TOP more acceptable than those who stated the opposite (AOR 95% CI: (5.6 (2.6–11.9); Table 4 ). Other factors found to be significant in the univariate comparisons (perceived health and perceived cancer risks) were no longer significant after multivariate adjustment.

Pregnant women’s theoretical intentions to have PGD/PND

The theoretical attitudes toward PGD/PND/TOP of the 16 women who were pregnant at the time of the survey did not differ significantly from those of the other women. However, the 11 women in this group who made spontaneous comments reacted in three ways: some were shocked by the idea (n = 4), while others felt that BRCA1/2 carrier status was not serious enough to justify PGD/PND (n = 4), and the last group (n = 3) said everybody should be free to decide for themselves.

Expectations about being informed about PGD/PND

There were no gender-related differences in the participants’ expectations about the delivery of PGD/PND information: 85.4% (n = 393) said this information should be systematically given along with the genetic test results and 44.8% (n = 206) answered “when carriers decide to have children.” Respondents expected this information to be given by cancer geneticists in 91.8% of cases (n = 422), by gyneco-obstetricians in 75.9% of cases (n = 349), and by general practitioners in 48.4% of cases (n = 223).

Discussion

This is the first time the reported effects of disclosure of BRCA1/2 carriers’ status on their ongoing childbearing plans and the factors contributing to their theoretical intentions to ask for PGD/PND have been documented in a national multicenter survey on unaffected male and female carriers of childbearing age. The results obtained show first that BRCA1/2 test result disclosure accelerated a few (mostly female) carriers’ decision to have a child; whereas in some cases, it made the respondents no longer want to have more children. ( Table 2 ) Second, the proportions of the respondents with future childbearing plans (16% and 44%) who said they would have PGD/PND, respectively, at a future theoretical next pregnancy were higher than we expected. Carriers’ PGD/PND theoretical intentions did not depend on gender or age but on whether or not they planned to have another child ( Table 3 ). The rate of acceptability of TOP by BRCA1/2 mutation carriers was low, but this factor strongly determined the respondents’ attitudes to both PGD and PND: 79% (181 out of 230) of the carriers who intended to have PND did not find TOP acceptable ( Table 4 ). The overall majority of the sample stated that information about PGD/PND should be delivered along with the genetic test results, preferably by cancer geneticists or gyneco-obstetricians.

Little attention has been paid so far to the issue of fertility in BRCA1/2 gene mutation carriers. One study on a large Utah-based kindred with an identified BRCA1 mutation has shown that female gene carriers’ intentions to have more children were lower than those of noncarriers, but not significantly so.12 In this study, it was observed that BRCA1/2 test results could slightly affect the number of additional children the respondents intended to have, and that they could impact the family planning process, as women’s childbearing plans were sometimes accelerated because of possibly having to undergo prophylactic oophorectomy.

In practice, PGD for BRCA1/2 carriers has rarely been reported,5,13 although several authors have examined the attitudes and factors involved in various groups (see Appendix).8,9,10,14,15,16 In two studies on women BRCA1/2 carriers, <15% said that they would consider having PGD themselves,10,14 although the great majority (75%) stated that information about PGD should be systematically provided.10,15 In another study, one-third of the men tested for BRCA1/2 or whose family members had been tested said that they would consider having PGD themselves.7 PGD and PND were said to be acceptable for BRCA1/2 carriers by 34% and 26% of the French cancer geneticists questioned, respectively.2 The results obtained in this study do not differ markedly from these previous findings.

In a large heterogeneous web-based sample of women, theoretical acceptability of PGD was found to be positively correlated with the desire to have more children.8 The present findings point to the opposite conclusion ( Table 2 ), as participants who had childbearing plans stated 3.5 times less frequently than the others that they intended to have PGD if they became pregnant. A similar negative trend was observed among those having many first-degree relatives with cancer, but the significance of this trend was only borderline ( Table 2 ). Here, it emerged that the closer people are to making a decision about PGD and the more they know about the experience of the carriers, the less likely they are to ask for PGD. The intention to have PND was correlated with positive attitudes toward TOP, but the discrepancy between PND intentions (50%) and TOP acceptability (12%) needs to be discussed. First, it is possible that some of the respondents may not have properly understood from the information provided in the questionnaire (see Appendix) that PND would be carried out only if TOP was felt to be acceptable when the fetus is affected. Second, it might mean that PND was simply regarded as a means of obtaining information about the carrier status of the fetus in order to be reassured (if there was no mutation), or to plan the future of the child (in the opposite case). These theoretical intentions may, therefore, not always be driven by the wish to possibly terminate the pregnancy. This issue has recently been studied in depth by Seror and Ville4 in the context of Down syndrome screening. These authors studied a cluster of women (37.0%) who expressed the opinion that obtaining information about their pregnancy should be the main objective when deciding about biochemical screening or invasive testing. A significant proportion of those who opted for PND in our study may have done so in order to obtain information about their fetus. This percentage is the same as that of the carriers in a North American study who declared that they intended to have their young children tested for BRCA1/2 mutations.17

The limitations of this study were that first it was based on participants’ purely theoretical declarative intentions and second, that the information about PGD/PND was delivered in standardized printed form and not tailored to the carriers’ personal characteristics and delivered in face-to-face interviews. Although previous studies had the same limitations, this point has to be taken into account when interpreting the findings. The results of further studies on carriers’ actual behavior will have to be compared with their theoretical intentions. Information about people’s a priori intentions is nevertheless useful, as it gives an idea as to how carriers are likely to react to the introduction of these new technologies. One of the main strengths of our study was the fact that this is the first time the majority of the sample surveyed corresponded to the population targeted for PGD/PND procedures in terms of their sociodemographics and health status. None of the previous studies included a large national nonselected sample of BRCA1/2 carriers, unaffected by cancer, males or females, in their reproductive age.

In this French national survey, it emerged that one out of six (16%) healthy BRCA1/2 carriers with future childbearing plans declared that they intended to have PGD for a next theoretical pregnancy if PGD was available, and that one out of ten female BRCA1/2 carriers stated that they felt TOP to be an acceptable strategy if their fetus turned out to be affected. These data do not differ very markedly from those obtained in other countries (see Supplementary Table S1 online), but they provide insights into the sociodemographic and other factors determining carriers’ a priori intentions toward PGD/PND. A lower educational level was found to be associated with a higher acceptability of PND and with a higher acceptability of TOP. Gender only modified significantly the attitudes toward TOP, women finding the intervention less acceptable than men. Age did not modify the acceptability of either intervention after multivariate adjustment. Carriers’ wish to be informed about the reproductive options available at BRCA1/2 test result disclosure may give rise to ethical dilemmas for the practitioners dispensing this information, especially in countries such as France, where the final decision about performing PGD/PND is made by an “ad hoc” multidisciplinary committee, which is unlikely to be in favor of these procedures.2 Cancer geneticists and cancer genetic counselors are not used to dispensing information about reproductive decision-making, and if they are to provide information of this kind, it will be necessary to involve health-care providers who are familiar with these reproductive procedures and able to answer all the questions BRCA1/2 carriers are liable to ask.

Appendix: Explanations Given in the Questionnaire About PGD/PND Procedures

You will find below a short description of the procedures involved in Preimplantation Diagnosis (PGD) and Prenatal diagnosis (PND).

Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis is an option when there is a high risk of parents transmitting a severe genetic disease to their offspring. A biological analysis carried out after in vitro fertilization (IVF) makes it possible to implant in the maternal uterus only healthy embryos not affected by the parental disorder.

IVF involves a hormonal method of ovarian stimulation which may increase the risk of cancer. Since this is a delicate intervention, only 20 women out of every 100 who undergo the PGD procedures will eventually give birth to a viable child.

In 5 to 10% of cases, PGD carries a risk of error. In view of this risk arising after a PGD, medical teams recommend amniocentesis as a means of prenatal diagnosis (PND) during the second trimester of pregnancy to make sure that the fetus is not affected by the genetic disease.

PGD enables parents to avoid having to think about the possibility of terminating pregnancy if the fetus is affected by the familial disease.

Prenatal Diagnosis (PND) makes it possible to determine during pregnancy whether or not the fetus is affected by a disease or by congenital abnormalities. When the disease is of a “particularly severe” kind and “no treatment is available,” a termination of pregnancy (TOP) can be proposed to the parents, provided the agreement of a multidisciplinary medical team has been obtained.

When PND is carried out by performing an amniocentesis, the risk of spontaneous fetal loss is about 1%.

Prenatal Diagnosis enables couples to conceive their children in a natural (nonmedically assisted) way.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Malkin D . Prenatal diagnosis, preimplantation genetic diagnosis, and cancer: was Hamlet wrong? J Clin Oncol 2009;27:4446–4447.

Julian-Reynier C, Chabal F, Frebourg T, et al. Professionals assess the acceptability of preimplantation genetic diagnosis and prenatal diagnosis for managing inherited predisposition to cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27: 4475–4480.

Aymé S, Briard ML, Mattei JF . Genetic services in France. Eur J Hum Genet 1997;5 Suppl 2:76–80.

Seror V, Ville Y . Women’s attitudes to the successive decisions possibly involved in prenatal screening for Down syndrome: how consistent with their actual decisions? Prenat Diagn 2010;30:1086–1093.

Sagi M, Weinberg N, Eilat A, et al. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis for BRCA1/2–a novel clinical experience. Prenat Diagn 2009;29:508–513.

Quinn GP, Vadaparampil ST, Bower B, Friedman S, Keefe DL . Decisions and ethical issues among BRCA carriers and the use of preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Minerva Med 2009;100:371–383.

Quinn GP, Vadaparampil ST, Miree CA, et al. High risk men’s perceptions of pre-implantation genetic diagnosis for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Hum Reprod 2010;25:2543–2550.

Vadaparampil ST, Quinn GP, Knapp C, Malo TL, Friedman S . Factors associated with preimplantation genetic diagnosis acceptance among women concerned about hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Genet Med 2009;11:757–765.

Fortuny D, Balmaña J, Graña B, et al. Opinion about reproductive decision making among individuals undergoing BRCA1/2 genetic testing in a multicentre Spanish cohort. Hum Reprod 2009;24:1000–1006.

Menon U, Harper J, Sharma A, et al. Views of BRCA gene mutation carriers on preimplantation genetic diagnosis as a reproductive option for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Hum Reprod 2007;22:1573–1577.

Andrieu N, Easton DF, Chang-Claude J, et al. Effect of chest X-rays on the risk of breast cancer among BRCA1/2 mutation carriers in the international BRCA1/2 carrier cohort study: a report from the EMBRACE, GENEPSO, GEO-HEBON, and IBCCS Collaborators’ Group. J Clin Oncol 2006;24: 3361–3366.

Smith KR, Ellington L, Chan AY, Croyle RT, Botkin JR . Fertility intentions following testing for a BRCA1 gene mutation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2004;13:733–740.

Jasper MJ, Liebelt J, Hussey ND . Preimplantation genetic diagnosis for BRCA1 exon 13 duplication mutation using linked polymorphic markers resulting in a live birth. Prenat Diagn 2008;28:292–298.

Staton AD, Kurian AW, Cobb K, Mills MA, Ford JM . Cancer risk reduction and reproductive concerns in female BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Fam Cancer 2008;7:179–186.

Quinn G, Vadaparampil S, Wilson C, et al. Attitudes of high-risk women toward preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Fertil Steril 2009;91:2361–2368.

Quinn GP, Vadaparampil ST, Tollin S, et al. BRCA carriers’ thoughts on risk management in relation to preimplantation genetic diagnosis and childbearing: when too many choices are just as difficult as none. Fertil Steril 2010;94:2473–2475.

Bradbury AR, Patrick-Miller L, Egleston B, et al. Parent opinions regarding the genetic testing of minors for BRCA1/2. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3498–3505.

Acknowledgements

We thank Anne Roque and Muriel Belotti for their technical help and all the GENEPSO cohort investigators, including Claude Adenis, Yves-Jean Bignon, Valérie Bonadona, Annie Chevrier, Chrystelle Colas, Odile Cohen-Haguenauer, Liliane Demange, Hélène Dreyfus, Catherine Dugast, François Eisinger, Marion Gauthiers-Villars, Laetitia Huiart, Jean-Marc Limacher, Michel Longy, Alain Lortholary, Elizabeth Luporsi, Sylviane Olschwang, Irwin Piot, Pascal Pujol, Laurence Venat-Bouvet, and Philippe Vennin. The GENEPSO study was supported by the Fondation de France and by La Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer; the psychosocial companion project was supported by the Institut National du Cancer (grant R08097AA/RPT08011AAA INCA) and the Agence de Biomédecine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table S1

(PDF 41 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Julian-Reynier, C., Fabre, R., Coupier, I. et al. BRCA1/2 carriers: their childbearing plans and theoretical intentions about having preimplantation genetic diagnosis and prenatal diagnosis. Genet Med 14, 527–534 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2011.27

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2011.27

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Knowledge, acceptability and personal attitude toward pre-implantation 1 genetic testing (PGT) and pre-natal diagnosis (PND) for females carrying BRCA pathogenic variant according to fertility preservation experience

Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics (2023)

-

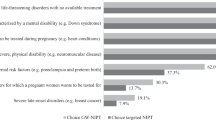

BRCA1/2 pathogenetic variant carriers and reproductive decisions: Gender differences and factors associated with the choice of preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) and prenatal diagnosis (PND)

Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics (2022)

-

Reproductive Decision‐Making in Women with BRCA1/2 Mutations

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2017)

-

Non‐invasive Prenatal Diagnosis for BRCA Mutations – a Qualitative Pilot Study of Health Professionals’ Views

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2016)

-

Impact of BRCA1/2 mutation on young women’s 5-year parenthood rates: a prospective comparative study (GENEPSO-PS cohort)

Familial Cancer (2015)