Abstract

Neurofibromatosis 1 is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by multiple café-au-lait spots, axillary and inguinal freckling, multiple cutaneous neurofibromas, and iris Lisch nodules. Learning disabilities are present in at least 50% of individuals with neurofibromatosis 1. Less common but potentially more serious manifestations include plexiform neurofibromas, optic nerve and other central nervous system gliomas, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, scoliosis, tibial dysplasia, and vasculopathy. The diagnosis of neurofibromatosis 1 is usually based on clinical findings. Neurofibromatosis 1, one of the most common Mendelian disorders, is caused by heterozygous mutations of the NF1 gene. Almost one half of all affected individuals have de novo mutations. Molecular genetic testing is available clinically but is infrequently needed for diagnosis. Disease management includes referral to specialists for treatment of complications involving the eye, central or peripheral nervous system, cardiovascular system, spine, or long bones. Surgery to remove both benign and malignant tumors or to correct skeletal manifestations is sometimes warranted. Annual physical examination by a physician familiar with the disorder is recommended. Other recommendations include ophthalmologic examinations annually in children and less frequently in adults, regular developmental assessment in children, regular blood pressure monitoring, and magnetic resonance imaging for follow-up of clinically suspected intracranial and other internal tumors.

Similar content being viewed by others

CLINICAL DESCRIPTION AND DIAGNOSIS

Neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) is an autosomal dominant condition caused by heterozygous mutations of the NF1 gene. The most frequent clinical manifestations are alterations of skin pigmentation, iris Lisch nodules, and multiple benign neurofibromas, but people with NF1 also frequently have learning disabilities and may develop skeletal abnormalities, vascular disease, central nervous system (CNS) tumors, or malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors.

NF1 is characterized by extreme clinical variability, not only among unrelated individuals and among affected individuals within a single family but also even within a single person at different times in life. Many people with NF1 have only milder manifestations of the disease, such as pigmentary lesions, Lisch nodules, or learning disabilities, but the frequency of more serious complications increases with age. Various manifestations of NF1 have different characteristic times of appearance.1–4

The average life expectancy of individuals with NF1 is reduced by ∼15 years.5,6 Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and vasculopathy are the most important causes of early death in individuals with NF1.

The criteria for diagnosis of NF1 developed by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Conference7 in 1987 are generally accepted for routine clinical use.4,8 The NIH diagnostic criteria are met in an individual who has two or more of the following features in the absence of another diagnosis:

-

Six or more café-au-lait macules (Fig. 1) >5 mm in greatest diameter in prepubertal individuals and >15 mm in greatest diameter in postpubertal individuals;

-

Two or more neurofibromas of any type (Figs. 2 and 3) or one plexiform neurofibroma (Fig. 4);

Fig. 2 -

Freckling in the axillary or inguinal regions;

-

Optic glioma;

-

Two or more Lisch nodules (iris hamartomas);

-

A distinctive osseous lesion such as sphenoid dysplasia or tibial pseudarthrosis; or

-

A first-degree relative with NF1 as defined by the above criteria.

These clinical criteria are both highly specific and highly sensitive in adults with NF1.8 In children, the diagnosis can be more problematical. Only approximately one half of the children with NF1 and no family history of NF1 meet the criteria for diagnosis by the age of 1 year, but almost all do by the age of 8 years9 because many features of NF1 increase in frequency with age.2,10,11

Children who have inherited NF1 from an affected parent can usually be identified within the first year of life because diagnosis requires just one feature in addition to a positive family history. This feature is usually multiple café-au-lait spots, which develop in infancy in >95% of individuals with NF1.2 Young children with multiple café-au-lait spots and no other NF1 features whose parents do not show signs of NF1 on careful physical and ophthalmologic examination should be strongly suspected of having NF1 and followed clinically as though they do. A definite diagnosis of NF1 can be made in most of these children by the age of 4 years using the NIH criteria.2

NATURAL HISTORY OF DISEASE MANIFESTATIONS

Cutaneous and subcutaneous manifestations

Café-au-lait spots are usually the first manifestation of NF1 observed. Café-au-lait spots are often present at birth and increase in number during the first few years of life. Multiple café-au-lait spots occur in nearly all affected individuals, and intertriginous freckling develops in almost 90%, usually by the age of 7 years.2

Neurofibromas are benign tumors arising from the Schwann cells that surround peripheral nerves of all sizes. Neurofibromas can occur anywhere in the peripheral nervous system.1 Several different kinds of neurofibromas exist, but their classification is controversial.1,11–14 Neurofibroma formation is most common in the skin but may affect virtually any organ in the body.

Discrete cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas are uncommon in early childhood. They usually begin to develop around the time of puberty, although small intradermal tumors can be seen using side lighting in many affected children. In adults with NF1, numerous cutaneous neurofibromas are usually present, but the total number varies from a few to many thousands. Additional cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas continue to develop throughout life, although the rate of appearance may vary greatly from year to year. Women may experience a burst of neurofibroma growth in association with pregnancy.

Plexiform neurofibromas

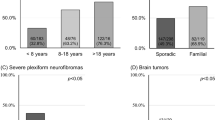

Approximately one half of people with NF1 have plexiform neurofibromas, but most are internal and not suspected clinically.15,16 Most of these tumors grow slowly if at all over periods of years, but rapid growth can occur in benign lesions, especially in early childhood.17,18 As a result of their extent and location, some plexiform neurofibromas cause disfigurement and may compromise function or even jeopardize life. Diffuse plexiform neurofibromas of the face and neck rarely appear after the age of 1 year, and diffuse plexiform neurofibromas of other parts of the body rarely develop after adolescence. In contrast, deep nodular plexiform neurofibromas, which often originate from spinal nerve roots, are infrequently seen in early childhood and usually remain asymptomatic even in adulthood.

Other neoplasms

In children with NF1, the most common neoplasms apart from neurofibromas are optic pathway gliomas and brain tumors.19–23 Approximately 15% of patients with NF1 develop optic pathway gliomas that are apparent on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before 6 years, but most are asymptomatic and remain so throughout life.20,24 Optic nerve pallor may be an important sign of optic pathway glioma. Symptomatic optic pathway gliomas in individuals with NF1 usually present before the age of 6 years with loss of visual acuity or proptosis, but these tumors may not become symptomatic until later in childhood or even in adulthood. Symptomatic optic pathway gliomas in NF1 are frequently stable for many years or only very slowly progressive; some of these tumors spontaneously regress.20,24–26

Brain tumors, which are usually gliomas of the brain stem or cerebellum, occur much more frequently than expected in people with NF1, especially in children and young adults. Second, CNS tumors occur in at least 20% of individuals with NF1 who have optic pathway gliomas in childhood27 and are substantially more frequent in patients with NF1 who previously had optic gliomas treated with radiotherapy.28 (Radiotherapy is no longer recommended for optic pathway gliomas in people with NF1—see “Treatment of Disease Manifestations” later). Brain tumors usually follow a less aggressive course in people with NF1 than in other individuals.22,23,29,30

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors are the most frequent malignant neoplasms associated with NF1, occurring sometime in the life of ∼10% of affected individuals.6,31–34 These malignancies tend to develop at a much younger age and have a poorer prognosis for survival in people with NF1 than in the general population.31,33–35 Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors are rare in children and adolescents with NF1, tend to be of low grade, and may be difficult to distinguish from atypical plexiform neurofibromas in this age group. High-grade malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors usually arise in patients with NF1 in their 20s or 30s.31,33,34

Individuals with NF1 who have benign subcutaneous neurofibromas or benign internal plexiform neurofibromas appear to be at greater risk of developing malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors than people with NF1 who lack such benign tumors.16,36 Two to 3% of people with NF137 develop a diffuse polyneuropathy that may be associated with multiple nerve root neurofibromas and a high risk of developing malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors.37,38 Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors also appear to be more frequent than expected in the therapeutic field in patients with NF1 who have had optic gliomas treated with radiotherapy.28,31

Leukemia, especially juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes, is infrequent in children with NF1 but much more common than in children without NF1. In one population-based study, women with NF1 appeared to have a 5-fold increased risk of developing breast cancer before the age of 50 years and a 3.5-fold increased risk of developing breast cancer overall.39 Gastrointestinal stromal tumors are also unusually frequent in people with NF1.40–44 NF1-associated and sporadic gastrointestinal stromal tumors appear to have different molecular pathogenesis, which has important implications in terms of therapy.40

Other ocular manifestations

Lisch nodules, which are innocuous iris hamartomas, aid in the diagnosis of NF1 but have no other clinical implications. Lisch nodules increase in frequency with age.45 They are not present at birth21 but can be found in >90% patients with NF1 aged 16 years or older.45

Vasculopathy

The prevalence of hypertension is more common in people with NF1 than in the general population and may develop at any age.1,46–48 In most cases, the hypertension is “essential,” but it may also occur as a consequence of renal artery stenosis and coarctation of the aorta or pheochromocytoma. A renovascular cause is often found in children with NF1 and hypertension.49,50

A characteristic NF1 vasculopathy can cause arterial stenosis, occlusion, aneurysm, pseudoaneurysm, rupture, or arteriovenous fistula formation. NF1 vasculopathy involving the arteries of the heart or brain or other major arteries can have serious or even fatal consequences.46,51–54 Cerebrovascular abnormalities may present in children with NF1 as stenoses or occlusions of the internal carotid, middle cerebral, or anterior cerebral artery. Small telangiectatic vessels form around the stenotic area and appear as a “puff of smoke” (moyamoya) on cerebral angiography.54 Moyamoya develops about three times more often than expected in children with NF1 after cranial irradiation for primary brain tumors.55 Ectatic vessels and intracranial aneurysms also occur more frequently in individuals with NF1 than in the general population.56,57 Valvular pulmonic stenosis is more common in individuals with NF1 than in the general population.58

Skeletal manifestations

Scoliosis has been reported in 10% to 26% of individuals affected with NF1 in various clinic-based series.59 There are two different forms—dystrophic and nondystrophic. The dystrophic form, which is progressive and associated with vertebral scalloping and wedging,60,61 almost always develops before 10 years, whereas the milder nondystrophic form of scoliosis typically occurs during adolescence.60

Long bone dysplasia, most often involving the tibia, occurs in 1% to 4% of children with NF1 in clinic-based series.59 In infants with tibial dysplasia, the bone is usually bowed in an anterolateral direction and is subject to pathologic fracture. Subsequent healing may not occur normally, producing pseudoarthrosis. The ipsilateral fibula is often involved in association with tibial pseudoarthrosis62 and focal dysplasia of the ulna, radius, scapula, or vertebra may occur.63

Although focal skeletal abnormalities like dystrophic scoliosis or tibial pseudoarthrosis can be severely disabling, they are uncommon among people with NF1. Generalized skeletal abnormalities are less severe but much more frequent. Individuals with NF1 tend to be below average in height and above average in head circumference for age,64–67 although heights >3 standard deviations below the mean and head circumferences >4 standard deviations above the mean are rarely seen.

Generalized osteopenia and frank osteoporosis are also more common than expected in people with NF1.68–74 The pathogenesis of these bony changes is not understood,75 but patients with NF1 may have lower than expected serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations, elevated serum parathyroid hormone levels, and evidence of increased bone resorption.72,74,76,77

Neurobehavioral abnormalities

Headaches occur frequently among individuals with NF1, and hydrocephalus or seizures are seen occasionally. People with NF1 have larger brains, on an average, than people without NF1, but gray matter volume is not correlated with intelligence quotient in NF1.78,79

Most individuals with NF1 have normal intelligence, but learning disabilities occur in 50% to 75%.80–85 Visual-spatial performance deficits and attention deficits are most often seen, although a variety of learning problems has been described. Children with NF1 often have poorer social skills and other personality, behavioral, and quality of life differences when compared with children without NF1.86–93 The learning problems associated with NF1 persist into adulthood.94,95

Unidentified bright objects (UBOs), which are sometimes called “T2 hyperintensities” or “focal areas of signal intensity”, can be visualized on T2-weighted MRI of the brain in at least 60% of children with NF1, but the clinical significance is uncertain.3,9,96–99 UBOs show no evidence of a mass effect and are not seen on T1-weighted MRI or on computed tomography scan. They may disappear with age.98,100,101 Some studies have suggested that the presence, number, volume, or location of UBOs correlate with learning disabilities in children with NF1, but the findings have not been consistent among investigations.97,100–103

Involvement of the endocrine and reproductive system

Precocious puberty may occur in children with NF1, especially in association with tumors of the optic chiasm.104 Delayed puberty is also common, but the reason it occurs is unknown.67 Although most children with NF1 are shorter than average,64–67 few are growth hormone deficient. Those who are may benefit from appropriate treatment.

Although most pregnancies in women with NF1 are normal, serious complications may develop. Hypertension may first become symptomatic or, if preexisting, may be greatly exacerbated during pregnancy.105 Many women with NF1 experience a rapid increase in the number and size of neurofibromas during pregnancy.106 Large pelvic or genital neurofibromas can complicate delivery, and cesarean section appears to be necessary more often than usual in pregnant women with NF1. Hormonal contraception does not appear to stimulate the growth of neurofibromas in women with NF1.76

Genotype-phenotype correlations

Only two clear correlations have been observed between particular mutant NF1 alleles and consistent clinical phenotypes. The first is a whole NF1 gene deletion associated with large numbers and early appearance of cutaneous neurofibromas, more frequent and more severe than average cognitive abnormalities, and sometimes somatic overgrowth, large hands and feet, and dysmorphic facial features.107–111 The second is a 3-bp in-frame deletion of Exon 17 (c.2970-2972 delAAT) associated with typical pigmentary features of NF1, but no cutaneous or surface plexiform neurofibromas.112

The consistent familial transmission of NF1 variants such as Watson syndrome (multiple café-au-lait spots, pulmonic stenosis, and dull intelligence)113,114 and familial spinal neurofibromatosis115–117 also indicates that allelic heterogeneity plays a role in the clinical variability of NF1. In addition, statistical analysis of clinical features in families with NF1 suggests that modifying genes at other loci influence some aspects of the NF1 phenotype.118–121 Conversely, the extreme clinical variability of NF1 suggests that random events are also important in determining the phenotype in affected individuals. Evidence in support of this interpretation is provided by the occurrence of acquired double inactivation of the NF1 locus in many different kinds of tumors and other focal lesions in people with NF1.117,120–139

Other distinctive NF1 phenotypes

Some individuals with NF1 have distinctive phenotypes composed of unusual combinations of clinical features that cluster together. Recognition of these distinctive phenotypes may aid in diagnosis and prognosis.

Segmental NF1

Segmental NF1 is diagnosed in individuals who have typical features of NF1 restricted to one part of the body and whose parents are both unaffected.140,141 In some cases, the unusual distribution of features may just be a chance occurrence in an individual with NF1. In other individuals, segmental NF1 represents mosaicism for a somatic NF1 mutation.132,142–144 However, most individuals who have been reported with mosaicism for an NF1 mutation have mild, but not segmental, neurofibromatosis.145 Individuals with segmental NF1 have been reported whose children have typical NF1.144,146

NF1-Noonan syndrome

Features of Noonan syndrome such as ocular hypertelorism, down-slanting palpebral fissures, low-set ears, webbed neck, and pulmonic stenosis occur in ∼12% of individuals with NF1.147 Relatives of such individuals who are affected with NF1 may or may not have concomitant features of Noonan syndrome. The NF1-Noonan phenotype appears to have a variety of causes, including the rare occurrence of two different autosomal dominant mutations in some families and segregation as an NF1 variant in others.148,149 Most individuals with NF1-Noonan syndrome have constitutional mutations of the NF1 gene.150–152 Mutations of the PTPN11 gene, which can be found in approximately one half of all people with Noonan syndrome, are uncommon but have been reported in people with the NF1-Noonan syndrome phenotype.150,153 Mutations found in Noonan syndrome and NF1 encode for different proteins involved in ras signaling, and it has been hypothesized that the phenotypic overlap is due to involvement of this shared pathway.154

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

More than 100 genetic conditions and multiple congenital anomaly syndromes have been described, which include café-au-lait spots or other individual features of NF1, but few of these disorders are ever confused with NF1. The conditions that are most often considered in the differential diagnosis of NF1 are listed in Table 1. In a few instances, an individual who does not have NF1 may meet the NF1 diagnostic criteria, but NF1 can be excluded because of the presence (or absence) of other characteristic features. For example, Legius syndrome, an autosomal dominant condition caused by heterozygous mutations of SPRED1, produces multiple café-au-lait spots, axillary freckling, macrocephaly and, in some individuals, facial features that resemble Noonan syndrome,155–157 but the absence of Lisch nodules and neurofibromas in affected adults makes NF1 unlikely in these families.

Another example is the condition caused by homozygosity for one of the genes associated with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC).158–160 This results in a cutaneous phenotype that is remarkably similar to NF1. However, individuals homozygous for mutations associated with HNPCC usually develop tumors that are typical of HNPCC with an even younger age of onset than seen in HNPCC heterozygotes. The parents of children who are homozygous for an HNPCC mutation are often consanguineous and may have clinical findings and/or a family history of HNPCC. Typically, neither parent has clinical findings of NF1.

Individuals or families have occasionally been described with pathogenic NF1 mutations who do not have NF1 according to the NIH Diagnostic Criteria. A few families have been reported in which affected individuals have NF1 mutations and multiple spinal neurofibromas but few, if any, cutaneous manifestations of the disease.115–117 Other examples include a human with an NF1 mutation and an optic pathway glioma but no other diagnostic features of NF1161 and a child with an NF1 mutation and encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis.162 The relationship of the NF1 mutations to the unusual phenotypes in these individuals is not understood.

MOLECULAR GENETICS

Pathogenesis

The NF1 gene was identified and the protein product characterized by Cawthon et al.163 and Wallace et al.164; the entire cDNA sequence was described by Gutmann and Collins165 and Viskochil et al.166 The gene is large (∼350 kb and 60 exons) and codes for at least three alternatively spliced transcripts.167 NF1 is unusual in that one of its introns contains coding sequences for at least three other genes.168 NF1 pseudogenes occur on chromosomes 2q21.1, 14q11.1, 14q11.2, 15q11.2, 18p11.21, 21q11.2-q21.1, and 22q11.1 (NCBI Entrez Gene), complicating the design of molecular assays for NF1 mutations.

The entire NF1 gene is located in an extended region of high linkage disequilibrium.169–171 Because recombination occurs infrequently within this 300-kb region, the haplotype structure in human populations is unusually simple.

NF1 is presumed to result from loss-of-function mutations because >80% of germline mutations described cause truncation of the gene product.172–174 In addition, deletion of the entire gene causes typical, although often severe, NF1. More than 500 different mutations of the NF1 gene have been identified; most are unique to a particular family. Many mutations have been observed repeatedly, but none has been found in more than a few percent of families studied.172 Many different kinds of mutations have been observed, including nonsense mutations, amino acid substitutions, deletions (which may involve only one or a few base pairs, multiple exons, or the entire gene), insertions, intronic changes affecting splicing, alterations of the 3′ untranslated region of the gene, and gross chromosomal rearrangements.

The protein product of the NF1 gene, neurofibromin, has a calculated molecular mass of ∼327 kDa. The function of neurofibromin is not fully understood, but it is known to activate ras GTPase, which promotes the hydrolysis of active ras-GTP to inactive ras-GDP.175–179 In NF1, reduction (in haploinsufficient cells) or complete loss (in cells that have also lost function of the normal NF1 allele) of neurofibromin leads to activation of ras, which in turn regulates a cascade of downstream signaling pathways, including those that involve mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), protein kinase B (PKB), and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) kinase. Activation of these pathways has a variety of cellular effects but generally stimulates cellular proliferation and survival.154

Neurofibromin probably has other functions as well, including regulation of adenylyl-cyclase activity and intracellular cyclic-AMP generation.175,176,180,181

Molecular genetic testing

Genetic testing is necessary to provide prenatal diagnosis and may be used as an adjunct to clinical diagnosis in cases with an atypical presentation or in which the child is too young to have developed most characteristic features. A multistep mutation detection protocol that identifies >95% of pathogenic NF1 mutations in individuals fulfilling the NIH diagnostic criteria is available.180,181 This protocol, which involves analysis of both mRNA and genomic DNA, includes real-time polymerase chain reaction, direct sequencing, microsatellite marker analysis, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification, and interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization. Because of the frequency of splicing mutations and the variety and rarity of individual mutations found in people with NF1, methods based solely on analysis of genomic DNA have lower detection rates.181,182

Testing by fluorescence in situ hybridization, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification, or analysis of multiple single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or other polymorphic genetic markers in the NF1 genomic region181 is sometimes performed to look just for whole NF1 gene deletions when the “large deletion phenotype” is suspected clinically.107,108 Whole NF1 gene deletions occur in 4% to 5% of individuals with NF1.183

Linkage studies are available, but they require accurate clinical diagnosis of NF1 in affected family members, accurate understanding of the genetic relationships in the family, and the availability and willingness of a sufficient number of family members to be tested. More than 1700 intragenic SNPs that can be used in linkage studies are currently listed for the NF1 locus in dbSNP.

MANAGEMENT

Initial evaluation

We recommend the following investigations to establish the extent of disease in an individual with NF1 at the time of diagnosis:

-

Personal medical history with particular attention to features of NF1;

-

Physical examination with particular attention to the skin, skeleton, cardiovascular system, and neurologic systems;

-

Ophthalmologic evaluation including slit lamp examination of the irises;

-

Developmental assessment in children;

-

Other studies as indicated on the basis of clinically apparent signs or symptoms.

The value of performing routine brain MRI in individuals with NF1 at the time of diagnosis is controversial. Proponents state that such studies are useful in helping to establish the diagnosis in some individuals, in identifying complications before they become clinically apparent in others, and in evaluating the context in which extracranial complications occur in still others.25,99,184 Those who oppose routine head MRI point to the difficulty in reliably diagnosing UBOs, the cost of such testing, the risk of sedation (which is necessary in a young child), and the fact that clinical management is not affected by finding intracranial lesions such as UBOs or optic nerve thickening in asymptomatic individuals.2,4,8,20,185,186 In fact, finding such lesions often results in regularly repeating the MRI despite the continued absence of related symptoms, adding further to the cost as well as to the anxiety of the individual and family, without any benefit. In addition, normal MRI findings on an initial scan do not preclude the subsequent development of CNS lesions.

Subsequent evaluation

Annual surveillance is recommended for people with NF1, with physical examination by a physician who is familiar with the individual and with the disease. In children and adolescents, height, weight, and head circumference should be measured and recorded on appropriate growth charts during each visit. The blood pressure should be measured on every visit, regardless of age. Annual ophthalmologic examination is especially important in early childhood, but eye examinations can be less frequent in older children and adults. In addition, children with NF1 should have regular developmental, speech, and language assessments, and those who appear to be manifesting developmental problems should have formal evaluation to provide a basis for appropriate intervention. Other studies should be performed as indicated on the basis of clinically apparent signs or symptoms. Patients with abnormalities of the CNS, skeletal system, or cardiovascular system should be referred to appropriate specialists for evaluation. Similar recommendations for the health supervision of individuals with NF1 have recently been made by others.4,8

No limitations on physical activity are necessary for most people with NF1. Limitations may be required if certain particular features, such as tibial dysplasia or dysplastic scoliosis, are present, but in these instances, the limitation is determined by the feature, not by the presence of NF1 itself.

Treatment of disease manifestations

Discrete cutaneous or subcutaneous neurofibromas that are disfiguring or in inconvenient locations (e.g., at belt or collar lines) can be removed surgically, or, if small, by laser or electrocautery. This aspect of treatment is important: disfigurement is the most distressing disease manifestation for many individuals with NF1.10

Plexiform neurofibromas may grow to enormous size and can cause serious disfigurement, overgrowth, or impingement on normal structures. The extent of plexiform neurofibromas seen on the surface of the body often cannot be determined by clinical examination alone, and many internal neurofibromas, even large ones, may be unsuspected on clinical examination. MRI is the method of choice for demonstrating the size and extent of plexiform neurofibromas16,187–189 and for monitoring their growth over time.17,18,190

Surgical treatment of plexiform neurofibromas is often unsatisfactory because of their intimate involvement with nerves and their tendency to grow back at the site of removal.175,191–195 In one small series in which surgical removal of superficial plexiform neurofibromas was undertaken in children while the tumors were still relatively small, it was possible to resect the neurofibromas completely without producing any neurological deficit.196 Completely resected tumors usually do not grow back, but this is not always the case.197 Various medical treatments for plexiform and spinal neurofibromas are currently being evaluated in clinical trials.4,175,177,198–200

Radiofrequency therapy has shown some promise for treatment of facial diffuse plexiform neurofibromas and café-au-lait spots in small clinical series.201,202 Radiotherapy of plexiform neurofibromas is contraindicated because of the risk of inducing malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors in these genetically predisposed individuals.27,31

Pain, development of a neurologic deficit, or enlargement of a preexisting quiescent plexiform neurofibroma may signal transformation to a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor and requires immediate evaluation.203 Examination by MRI and positron emission tomography187,204–210 is useful in distinguishing benign and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, but definitive differentiation can only be made by histological examination of the tumor. Complete surgical excision, when possible, is the only treatment that offers the possibility of cure of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy is sometimes used as well, although benefit has not been clearly established.33,175,194 Clinical trials of several therapeutic approaches to malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors are available to individuals with NF1.175,177

Most children with NF1 who develop optic pathway gliomas do not require treatment, but chemotherapy is the treatment of choice for progressive tumors.20,24,26,211,212 Surgical treatment of optic pathway gliomas is usually reserved for cosmetic palliation in a blind eye, and radiotherapy is usually avoided because of the risk of inducing malignancy or moyamoya in the exposed field.31,56 Several controlled trials for treatment of optic pathway gliomas are available to individuals with NF1.20,211

The less aggressive course of most brainstem and cerebellar gliomas in people with NF1 should be taken into consideration in the management of these tumors.22,23,29,30

Bracing is usually ineffective in children with NF1 and rapidly progressive dystrophic scoliosis. Treatment requires surgery, which may be complex and difficult.213,214 Nondystrophic scoliosis in adolescents with NF1 can usually be treated in a manner similar to idiopathic scoliosis in the general population.

Medications that are useful for treatment of attention-deficit hyperactive disorder, depression, or anxiety in the general population are also effective for individuals with NF1 and can be prescribed if indicated.

GENETIC COUNSELING

NF1 is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. Approximately 50% of individuals with NF1 have been found to have an affected parent, and ∼50% have the altered gene as a result of de novo mutation, at least in North American and European populations that have been well studied. When NF1 is suspected in a child, both parents should have medical histories, physical examinations, and ophthalmological examinations (including slit lamp examination) performed with particular attention to features of NF1. Diagnosis of NF1 in a parent may permit unequivocal diagnosis of NF1 in a child, is essential for genetic counseling, and has important medical implications for the affected parent.

The risk to the sibs of a proband depends on whether one of the proband's parents has NF1. If a parent is affected, the risk to the sibs is 50%. If neither parent of an individual with NF1 meets the clinical diagnostic criteria for NF1 after careful medical history, physical examination, and ophthalmologic examination, the risk to the sibs of the affected individual of having NF1 is low but greater than that of the general population because of the possibility of germline mosaicism.144,215

Each child of an individual with NF1 has a 50% chance of inheriting the mutant gene. Penetrance is 100%, so a child who inherits an NF1 mutation will develop features of NF1, but the disease may be considerably more (or less) severe in an affected children than in their affected parent. The risk to other family members depends on the status of the proband's parents. If a parent is found to be affected, their own parents and other children are at risk.

The optimal time for determination of genetic risk and genetic counseling regarding prenatal testing is before pregnancy. It is appropriate to offer genetic counseling (including discussion of potential risks to offspring and reproductive options) to young adults who are affected or at risk.

Prenatal diagnosis for pregnancies at increased risk for NF1 is available by analysis of DNA extracted from fetal cells obtained by amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling. Preimplantation diagnosis of NF1 has also been reported.216–218 The disease-causing allele in the affected parent must be identified before prenatal or preimplantation testing can be performed.219,220 Prenatal diagnosis can also be performed by linkage,220 but NF1 is a relatively common autosomal dominant condition and families have been reported with two or even three different NF1 mutations segregating in affected relatives.168,221 The occurrence of two or more different pathogenic mutations in a family could confound the use of linkage analysis for prenatal diagnosis. Prenatal diagnosis of exceptionally severe NF1 by ultrasound examination has been reported,222 but ultrasound examination is unlikely to be informative in most cases.

Requests for prenatal testing for NF1 are not common, probably because of the wide range of severity and age of onset. Differences in perspective may exist among medical professionals and within families regarding the use of prenatal testing, particularly if the testing is being considered for the purpose of pregnancy termination rather than early diagnosis. Discussion of these issues is appropriate during pretest counseling for prenatal diagnosis of NF1.

REFERENCES

Friedman JM, Riccardi VM . Clinical epidemiological features. In: FriedmaFriedman JM, Gutmann DH, MacCollin M, Riccardi VM, editors. Neurofibromatosis: phenotype, natural history, and pathogenesis. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp 1999; 29–86.

DeBella K, Szudek J, Friedman JM . Use of the national institutes of health criteria for diagnosis of neurofibromatosis 1 in children. Pediatrics 2000; 105: 608–614.

Boulanger JM, Larbrisseau A . Neurofibromatosis type 1 in a pediatric population: Ste-Justine's experience. Can J Neurol Sci 2005; 32: 225–231.

Williams VC, Lucas J, Babcock MA, Gutmann DH, Korf B, Maria BL . Neurofibromatosis type 1 revisited. Pediatrics 2009; 123: 124–133.

Zoller M, Rembeck B, Akesson HO, Angervall L . Life expectancy, mortality and prognostic factors in neurofibromatosis type 1. A twelve-year follow-up of an epidemiological study in Goteborg, Sweden. Acta Derm Venereol 1995; 75: 136–140.

Rasmussen SA, Yang Q, Friedman JM . Mortality in neurofibromatosis 1: an analysis using U.S. death certificates. Am J Hum Genet 2001; 68: 1110–1118.

NIH Consensus Development Conference. Neurofibromatosis. Conference statement. Arch Neurol 1988; 45: 575–578.

Ferner RE, Huson SM, Thomas N, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of individuals with neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1). J Med Genet 2007; 44: 81–88.

DeBella K, Poskitt K, Szudek J, Friedman JM . Use of “unidentified bright objects” on MRI for diagnosis of neurofibromatosis 1 in children. Neurology 2000; 54: 1646–1651.

Wolkenstein P, Durand-Zaleski I, Moreno JC, Zeller J, Hemery F, Revuz J . Cost evaluation of the medical management of neurofibromatosis 1: a prospective study on 201 patients. Br J Dermatol 2000; 142: 1166–1170.

Friedman JM, Birch PH . Type 1 neurofibromatosis: a descriptive analysis of the disorder in 1,728 patients. Am J Med Genet 1997; 70: 138–143.

Riccardi VM . The genetic predisposition to and histogenesis of neurofibromas and neurofibrosarcoma in neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurosurg Focus 2007; 22: E3.

Woodruff JM . Pathology of tumors of the peripheral nerve sheath in type 1 neurofibromatosis. Am J Med Genet 1999; 89: 23–30.

Mautner VF, Hartmann M, Kluwe L, Friedrich RE, Funsterer C . MRI growth patterns of plexiform neurofibromas in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Neuroradiology 2006; 48: 160–165.

Tonsgard JH, Kwak SM, Short MP, Dachman AH . CT imaging in adults with neurofibromatosis-1: frequent asymptomatic plexiform lesions. Neurology 1998; 50: 1755–1760.

Mautner VF, Asuagbor FA, Dombi E, et al. Assessment of benign tumor burden by whole-body MRI in patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Neuro Oncol 2008; 10: 593–598.

Dombi E, Solomon J, Gillespie AJ, et al. NF1 plexiform neurofibroma growth rate by volumetric MRI: relationship to age and body weight. Neurology 2007; 68: 643–647.

Tucker T, Friedman JM, Friedrich RE, Wenzel R, Fünsterer C, Mautner VF . Longitudinal study of neurofibromatosis 1 associated plexiform neurofibromas. J Med Genet 2009; 46: 81–85.

Listernick R, Gutmann DH . Tumors of the optic pathway. In: Friedman JM, Gutmann DH, MacCollin M, Riccardi VM, editors. Neurofibromatosis: phenotype, natural history, and pathogenesis. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999; 203–230.

Listernick R, Ferner RE, Liu GT, Gutmann DH . Optic pathway gliomas in neurofibromatosis-1: controversies and recommendations. Ann Neurol 2007; 61: 189–198.

Kreusel KM . Ophthalmological manifestations in VHL and NF 1: pathological and diagnostic implications. Fam Cancer 2005; 4: 43–47.

Korf BR . Malignancy in neurofibromatosis type 1. Oncologist 2000; 5: 477–485.

Ullrich NJ, Raja AI, Irons MB, Kieran MW, Goumnerova L . Brainstem lesions in neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurosurgery 2007; 61: 762–766; discussion 766–767.

Sylvester CL, Drohan LA, Sergott RC . Optic-nerve gliomas, chiasmal gliomas and neurofibromatosis type 1. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2006; 17: 7–11.

Blazo MA, Lewis RA, Chintagumpala MM, Frazier M, McCluggage C, Plon SE . Outcomes of systematic screening for optic pathway tumors in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Med Genet A 2004; 127: 224–229.

Shamji MF, Benoit BG . Syndromic and sporadic pediatric optic pathway gliomas: review of clinical and histopathological differences and treatment implications. Neurosurg Focus 2007; 23: E3.

Sharif S, Ferner R, Birch JM, et al. Second primary tumors in neurofibromatosis 1 patients treated for optic glioma: substantial risks after radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 2570–2575.

Kleinerman RA . Radiation-sensitive genetically susceptible pediatric sub populations. Pediatr Radiol 2009; 39 ( suppl 1): S27–S31.

Vinchon M, Soto-Ares G, Ruchoux MM, Dhellemmes P . Cerebellar gliomas in children with NF1: pathology and surgery. Childs Nerv Syst 2000; 16: 417–420.

Rosser T, Packer RJ . Intracranial neoplasms in children with neurofibromatosis 1. J Child Neurol 2002; 17: 630–637.

Evans DG, Baser ME, McGaughran J, Sharif S, Howard E, Moran A . Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours in neurofibromatosis 1. J Med Genet 2002; 39: 311–314.

Walker L, Thompson D, Easton D, et al. A prospective study of neurofibromatosis type 1 cancer incidence in the UK. Br J Cancer 2006; 95: 233–238.

Friedrich RE, Hartmann M, Mautner VF . Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST) in NF1-affected children. Anticancer Res 2007; 27: 1957–1960.

McCaughan JA, Holloway SM, Davidson R, Lam WW . Further evidence of the increased risk for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour from a Scottish cohort of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. J Med Genet 2007; 44: 463–466.

Hagel C, Zils U, Peiper M, et al. Histopathology and clinical outcome of NF1-associated vs. sporadic malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. J Neurooncol 2007; 82: 187–192.

Tucker T, Wolkenstein P, Revuz J, Zeller J, Friedman JM . Association between benign and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors in NF1. Neurology 2005; 65: 205–211.

Drouet A, Wolkenstein P, Lefaucheur JP, et al. Neurofibromatosis 1-associated neuropathies: a reappraisal. Brain 2004; 127: 1993–2009.

Ferner RE, Hughes RA, Hall SM, Upadhyaya M, Johnson MR . Neurofibromatous neuropathy in neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1). J Med Genet 2004; 41: 837–841.

Sharif S, Moran A, Huson SM, et al. Women with neurofibromatosis 1 are at a moderately increased risk of developing breast cancer and should be considered for early screening. J Med Genet 2007; 44: 481–484.

Andersson J, Sihto H, Meis-Kindblom JM, Joensuu H, Nupponen N, Kindblom LG . NF1-associated gastrointestinal stromal tumors have unique clinical, phenotypic, and genotypic characteristics. Am J Surg Pathol 2005; 29: 1170–1176.

Takazawa Y, Sakurai S, Sakuma Y, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of neurofibromatosis type I (von Recklinghausen's disease). Am J Surg Pathol 2005; 29: 755–763.

Miettinen M, Fetsch JF, Sobin LH, Lasota J . Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis 1: a clinicopathologic and molecular genetic study of 45 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2006; 30: 90–96.

Kramer K, Hasel C, Aschoff AJ, Henne-Bruns D, Wuerl P . Multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors and bilateral pheochromocytoma in neurofibromatosis. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13: 3384–3387.

Guillaud O, Dumortier J, Bringuier PP, et al. [Multiple gastro-intestinal stromal tumors (GIST) in a patient with type I neurofibromatosis revealed by chronic bleeding: pre-operative radiological diagnosis]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2006; 30: 320–324 [ in French].

Huson S, Jones D, Beck L . Ophthalmic manifestations of neurofibromatosis. Br J Ophthalmol 1987; 71: 235–238.

Friedman JM, Arbiser J, Epstein JA, et al. Cardiovascular disease in neurofibromatosis 1: report of the NF1 Cardiovascular Task Force. Genet Med 2002; 4: 105–111.

Lama G, Graziano L, Calabrese E, et al. Blood pressure and cardiovascular involvement in children with neurofibromatosis type1. Pediatr Nephrol 2004; 19: 413–418.

Tedesco MA, Di Salvo G, Ratti G, et al. Arterial distensibility and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in young patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Hypertens 2001; 14( 6): 559–566.

Fossali E, Signorini E, Intermite RC, et al. Renovascular disease and hypertension in children with neurofibromatosis. Pediatr Nephrol 2000; 14: 806–810.

Han M, Criado E . Renal artery stenosis and aneurysms associated with neurofibromatosis. J Vasc Surg 2005; 41: 539–543.

Tang SC, Lee MJ, Jeng JS, Yip PK . Novel mutation of neurofibromatosis type 1 in a patient with cerebral vasculopathy and fatal ischemic stroke. J Neurol Sci 2006; 243: 53–55.

Tatebe S, Asami F, Shinohara H, Okamoto T, Kuraoka S . Ruptured aneurysm of the subclavian artery in a patient with von Recklinghausen's disease. Circ J 2005; 69: 503–506.

Kanter RJ, Graham M, Fairbrother D, Smith SV . Sudden cardiac death in young children with neurofibromatosis type 1. J Pediatr 2006; 149: 718–720.

Cairns AG, North KN . Cerebrovascular dysplasia in neurofibromatosis type 1. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008; 79: 1165–1170.

Ullrich NJ, Robertson R, Kinnamon DD, et al. Moyamoya following cranial irradiation for primary brain tumors in children. Neurology 2007; 68: 932–938.

Rosser TL, Vezina G, Packer RJ . Cerebrovascular abnormalities in a population of children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurology 2005; 64: 553–555.

Schievink WI, Riedinger M, Maya MM . Frequency of incidental intracranial aneurysms in neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Med Genet A 2005; 134: 45–48.

Lin AE, Birch PH, Korf BR, et al. Cardiovascular malformations and other cardiovascular abnormalities in neurofibromatosis 1. Am J Med Genet 2000; 95: 108–117.

Alwan S, Tredwell SJ, Friedman JM . Is osseous dysplasia a primary feature of neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1)?. Clin Genet 2005; 67: 378–390.

Funasaki H, Winter RB, Lonstein JB, Denis F . Pathophysiology of spinal deformities in neurofibromatosis. An analysis of seventy-one patients who had curves associated with dystrophic changes. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994; 76: 692–700.

Restrepo C, Riascos R, Hatta A, Rojas R . Neurofibromatosis type 1: spinal manifestations of a systemic disease. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2005; 29: 532–539.

Stevenson DA, Birch PH, Friedman JM, et al. Descriptive analysis of tibial pseudoarthrosis in patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Am J Med Genet 1999; 84: 413–419.

Vitale MG, Guha A, Skaggs DL . Orthopaedic manifestations of neurofibromatosis in children: an update. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002; 401: 107–118.

Clementi M, Milani S, Mammi I, Boni S, Monciotti C, Tenconi R . Neurofibromatosis type 1 growth charts. Am J Med Genet 1999; 87: 317–323.

Szudek J, Birch P, Friedman JM . Growth charts for young children with neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1). Am J Med Genet 2000; 92: 224–228.

Szudek J, Birch P, Friedman JM . Growth in North American white children with neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1). J Med Genet 2000; 37: 933–938.

Virdis R, Street ME, Bandello MA, et al. Growth and pubertal disorders in neurofibromatosis type 1. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2003; 16 ( suppl 2): 289–292.

Kuorilehto T, Pöyhönen M, Bloigu R, Heikkinen J, Väänänen K, Peltonen J . Decreased bone mineral density and content in neurofibromatosis type 1: lowest local values are located in the load-carrying parts of the body. Osteoporos Int 2005; 16: 928–936.

Lammert M, Kappler M, Mautner VF, et al. Decreased bone mineral density in patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Osteoporos Int 2005; 16: 1161–1166.

Dulai S, Briody J, Schindeler A, North KN, Cowell CT, Little DG . Decreased bone mineral density in neurofibromatosis type 1: results from a pediatric cohort. J Pediatr Orthop 2007; 27: 472–475.

Yilmaz K, Ozmen M, Bora Goksan S, Eskiyurt N . Bone mineral density in children with neurofibromatosis 1. Acta Paediatr 2007; 96: 1220–1222.

Brunetti-Pierri N, Doty SB, Hicks J, et al. Generalized metabolic bone disease in neurofibromatosis type I. Mol Genet Metab 2008; 94: 105–111.

Duman O, Ozdem S, Turkkahraman D, Olgac ND, Gungor F, Haspolat S . Bone metabolism markers and bone mineral density in children with neurofibromatosis type-1. Brain Dev 2008; 30: 584–588.

Tucker T, Schnabel C, Hartmann M, et al. Bone health and fracture rate in individuals with NF1. J Med Genet 2009; 46: 259–265.

Schindeler A, Little DG . Recent insights into bone development, homeostasis, and repair in type 1 neurofibromatosis (NF1). Bone 2008; 42: 616–622.

Lammert M, Friedman JM, Roth HJ, et al. Vitamin D deficiency associated with number of neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis 1. J Med Genet 2006; 43: 810–813.

Stevenson DA, Schwarz EL, Viskochil DH, et al. Evidence of increased bone resorption in neurofibromatosis type 1 using urinary pyridinium crosslink analysis. Pediatr Res 2008; 63: 697–701.

Greenwood RS, Tupler LA, Whitt JK, et al. Brain morphometry, T2-weighted hyperintensities, and IQ in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Arch Neurol 2005; 62: 1904–1908.

Margariti PN, Blekas K, Katzioti FG, Zikou AK, Tzoufi M, Argyropoulou MI . Magnetization transfer ratio and volumetric analysis of the brain in macrocephalic patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Eur Radiol 2007; 17: 433–438.

Hyman SL, Shores A, North KN . The nature and frequency of cognitive deficits in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurology 2005; 65: 1037–1044.

Hyman SL, Arthur Shores E, North KN . Learning disabilities in children with neurofibromatosis type 1: subtypes, cognitive profile, and attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol 2006; 48: 973–977.

Krab LC, Aarsen FK, de Goede-Bolder A, et al. Impact of neurofibromatosis type 1 on school performance. J Child Neurol 2008; 23: 1002–1010.

Coudé FX, Mignot C, Lyonnet S, Munnich A . Academic impairment is the most frequent complication of neurofibromatosis type-1 (NF1) in children. Behav Genet 2006; 36: 660–664.

Levine TM, Materek A, Abel J, O'Donnell M, Cutting LE . Cognitive profile of neurofibromatosis type 1. Semin Pediatr Neurol 2006; 13: 8–20.

Watt SE, Shores A, North KN . An examination of lexical and sublexical reading skills in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Child Neuropsychol 2008; 14: 401–418.

Prinzie P, Descheemaeker MJ, Vogels A, et al. Personality profiles of children and adolescents with neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Med Genet A 2003; 118: 1–7.

Barton B, North K . Social skills of children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Dev Med Child Neurol 2004; 46: 553–563.

Barton B, North K . The self-concept of children and adolescents with neurofibromatosis type 1. Child Care Health Dev 2007; 33: 401–408.

Graf A, Landolt MA, Mori AC, Boltshauser E . Quality of life and psychological adjustment in children and adolescents with neurofibromatosis type 1. J Pediatr 2006; 149: 348–353.

Johnson H, Wiggs L, Stores G, Huson SM . Psychological disturbance and sleep disorders in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Dev Med Child Neurol 2005; 47: 237–242.

Noll RB, Reiter-Purtill J, Moore BD, et al. Social, emotional, and behavioral functioning of children with NF1. Am J Med Genet A 2007; 143: 2261–2273.

Page PZ, Page GP, Ecosse E, Korf BR, Leplege A, Wolkenstein P . Impact of neurofibromatosis 1 on quality of life: a cross-sectional study of 176 American cases. Am J Med Genet A 2006; 140: 1893–1898.

Krab LC Oostenbrink R de Goede-Bolder A Aarsen FK Elgersma Y Moll HA . Health-related quality of life in children with neurofibromatosis type 1: contribution of demographic factors, disease-related factors, and behavior. J Pediatr. In press.

Pavol M, Hiscock M, Massman P, Moore Iii B, Foorman B, Meyers C . Neuropsychological function in adults with von Recklinghausen's neurofibromatosis. Dev Neuropsychol 2006; 29: 509–526.

Uttner I, Wahllander-Danek U, Danek A . Cognitive impairment in adults with neurofibromatosis type 1. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 2003; 71: 157–162.

Curless RG . Use of “unidentified bright objects” on MRI for diagnosis of neurofibromatosis 1 in children. Neurology 2000; 55: 1067–1068.

Goh WH, Khong PL, Leung CS, Wong VC . T2-weighted hyperintensities (unidentified bright objects) in children with neurofibromatosis 1: their impact on cognitive function. J Child Neurol 2004; 19: 853–858.

Gill DS, Hyman SL, Steinberg A, North KN . Age-related findings on MRI in neurofibromatosis type 1. Pediatr Radiol 2006; 36: 1048–1056.

Lopes Ferraz Filho JR, Munis MP, Soares Souza A, Sanches RA, Goloni-Bertollo EM, Pavarino-Bertelli EC . Unidentified bright objects on brain MRI in children as a diagnostic criterion for neurofibromatosis type 1. Pediatr Radiol 2008; 38: 305–310.

Hyman SL, Gill DS, Shores EA, et al. Natural history of cognitive deficits and their relationship to MRI T2-hyperintensities in NF1. Neurology 2003; 60: 1139–1145.

Feldmann R, Denecke J, Grenzebach M, Schuierer G, Weglage J . Neurofibromatosis type 1: motor and cognitive function and T2-weighted MRI hyperintensities. Neurology 2003; 61: 1725–1728.

North K Cognitive function and academic performance. In: FriedmaFriedman JM, Gutmann DH, MacCollin M, Riccardi VM, editors, Neurofibromatosis: phenotype, natural history, and pathogenesis. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999; 162–189.

Hyman SL, Gill DS, Shores EA, Steinberg A, North KN . T2 hyperintensities in children with neurofibromatosis type 1 and their relationship to cognitive functioning. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007; 78: 1088–1091.

Virdis R, Sigorini M, Laiolo A, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1 and precocious puberty. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2000; 13 ( suppl 2): 841–844.

Dugoff L, Sujansky E . Neurofibromatosis type 1 and pregnancy. Am J Med Genet 1996; 66: 7–10.

Roth TM, Petty EM, Barald KF . The role of steroid hormones in the NF1 phenotype: focus on pregnancy. Am J Med Genet A 2008; 146: 1624–1633.

Upadhyaya M, Ruggieri M, Maynard J, et al. Gross deletions of the neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) gene are predominantly of maternal origin and commonly associated with a learning disability, dysmorphic features and developmental delay. Hum Genet 1998; 102: 591–597.

Riva P, Corrado L, Natacci F, et al. NF1 microdeletion syndrome: refined FISH characterization of sporadic and familial deletions with locus-specific probes. Am J Hum Genet 2000; 66: 100–109.

Venturin M, Guarnieri P, Natacci F, et al. Mental retardation and cardiovascular malformations in NF1 microdeleted patients point to candidate genes in 17q11.2. J Med Genet 2004; 41: 35–41.

Spiegel M, Oexle K, Horn D, et al. Childhood overgrowth in patients with common NF1 microdeletions. Eur J Hum Genet 2005; 13: 883–888.

Mensink KA, Ketterling RP, Flynn HC, et al. Connective tissue dysplasia in five new patients with NF1 microdeletions: further expansion of phenotype and review of the literature. J Med Genet 2006; 43: e8.

Upadhyaya M, Huson SM, Davies M, et al. An absence of cutaneous neurofibromas associated with a 3-bp inframe deletion in exon 17 of the NF1 gene (c. 2970-2972 delAAT): evidence of a clinically significant NF1 genotype-phenotype correlation. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 80: 140–151.

Allanson JE, Upadhyaya M, Watson GH, et al. Watson syndrome: is it a subtype of type 1 neurofibromatosis?. J Med Genet 1991; 28: 752–756.

Tassabehji M, Strachan T, Sharland M, et al. Tandem duplication within a neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) gene exon in a family with features of Watson syndrome and Noonan syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 1993; 53: 90–95.

Kaufmann D, Muller R, Bartelt B, et al. Spinal neurofibromatosis without cafe-au-lait macules in two families with null mutations of the NF1 gene. Am J Hum Genet 2001; 69: 1395–1400.

Kluwe L, Tatagiba M, Funsterer C, Mautner VF . NF1 mutations and clinical spectrum in patients with spinal neurofibromas. J Med Genet 2003; 40: 368–371.

Upadhyaya M, Spurlock G, Kluwe L, et al. The spectrum of somatic and germline NF1 mutations in NF1 patients with spinal neurofibromas. Neurogenetics 2009; 10: 251–263.

Easton DF, Ponder MA, Huson SM, Ponder BA . An analysis of variation in expression of neurofibromatosis (NF) type 1 (NF1): evidence for modifying genes. Am J Hum Genet 1993; 53: 305–313.

Sabbagh A, Pasmant E, Laurendeau I, et al. Members of the NF France Network Unraveling the genetic basis of variable clinical expression in neurofibromatosis 1. Hum Mol Genet 2009; 18: 2768–2778.

Szudek J, Birch P, Riccardi VM, Evans DG, Friedman JM . Associations of clinical features in neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1). Genet Epidemiol 2000; 19: 429–439.

Szudek J, Joe H, Friedman JM . Analysis of intrafamilial phenotypic variation in neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1). Genet Epidemiol 2002; 23: 150–164.

Xu W, Mulligan LM, Ponder MA, et al. Loss of NF1 alleles in phaeochromocytomas from patients with type I neurofibromatosis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1992; 4: 337–342.

Gutmann DH, Donahoe J, Brown T, James CD, Perry A . Loss of neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) gene expression in NF1-associated pilocytic astrocytomas. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2000; 26: 361–367.

Gutmann DH, James CD, Poyhonen M, et al. Molecular analysis of astrocytomas presenting after age 10 in individuals with NF1. Neurology 2003; 61: 1397–1400.

Tada K, Kochi M, Saya H, et al. Preliminary observations on genetic alterations in pilocytic astrocytomas associated with neurofibromatosis 1. Neuro Oncol 2003; 5: 228–234.

Frahm S, Mautner VF, Brems H, et al. Genetic and phenotypic characterization of tumor cells derived from malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors of neurofibromatosis type 1 patients. Neurobiol Dis 2004; 16: 85–91.

Upadhyaya M, Han S, Consoli C, et al. Characterization of the somatic mutational spectrum of the neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) gene in neurofibromatosis patients with benign and malignant tumors. Hum Mutat 2004; 23: 134–146.

De Raedt T, Maertens O, Chmara M, et al. Somatic loss of wild type NF1 allele in neurofibromas: Comparison of NF1 microdeletion and non-microdeletion patients. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2006; 45: 893–904.

Maertens O, Brems H, Vandesompele J, et al. Comprehensive NF1 screening on cultured Schwann cells from neurofibromas. Hum Mutat 2006; 27: 1030–1040.

Rübben A, Bausch B, Nikkels A . Somatic deletion of the NF1 gene in a neurofibromatosis type 1-associated malignant melanoma demonstrated by digital PCR. Mol Cancer 2006; 5: 36.

Stephens K, Weaver M, Leppig KA, et al. Interstitial uniparental isodisomy at clustered breakpoint intervals is a frequent mechanism of NF1 inactivation in myeloid malignancies. Blood 2006; 108: 1684–1689.

Maertens O, De Schepper S, Vandesompele J, et al. Molecular dissection of isolated disease features in mosaic neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 81: 243–251.

Stewart DR, Corless CL, Rubin BP, et al. Mitotic recombination as evidence of alternative pathogenesis of gastrointestinal stromal tumours in neurofibromatosis type 1. J Med Genet 2007; 44: e61.

Spurlock G, Griffiths S, Uff J, Upadhyaya M . Somatic alterations of the NF1 gene in an NF1 individual with multiple benign tumours (internal and external) and malignant tumour types. Fam Cancer 2007; 6: 463–471.

Bottillo I, Ahlquist T, Brekke H, et al. Germline and somatic NF1 mutations in sporadic and NF1-associated malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours. J Pathol 2008; 217: 693–701.

De Schepper S, Maertens O, Callens T, Naeyaert JM, Lambert J, Messiaen L . Somatic mutation analysis in NF1 café-au-lait spots reveals two NF1 hits in the melanocytes. J Invest Dermatol 2008; 128: 1050–1053.

Upadhyaya M, Spurlock G, Monem B, et al. Germline and somatic NF1 gene mutations in plexiform neurofibromas. Hum Mutat 2008; 29: E103–E111.

Stevenson DA, Zhou H, Ashrafi S, et al. Double inactivation of NF1 in tibial pseudarthrosis. Am J Hum Genet 2006; 79: 143–148.

Steinmann K, Kluwe L, Friedrich RE, Mautner VF, Cooper DN, Kehrer-Sawatzki H . Mechanisms of loss of heterozygosity in neurofibromatosis type 1-associated plexiform neurofibromas. J Invest Dermatol 2009; 129: 615–621.

Listernick R, Mancini AJ, Charrow J . Segmental neurofibromatosis in childhood. Am J Med Genet A 2003; 121: 132–135.

Ruggieri M, Huson SM . The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology 2001; 56: 1433–1443.

Tinschert S, Naumann I, Stegmann E, et al. Segmental neurofibromatosis is caused by somatic mutation of the neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) gene. Eur J Hum Genet 2000; 8: 455–459.

Vandenbroucke I, van Doorn R, Callens T, Cobben JM, Starink TM, Messiaen L . Genetic and clinical mosaicism in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. Hum Genet 2004; 114: 284–290.

Consoli C, Moss C, Green S, Balderson D, Cooper DN, Upadhyaya M . Gonosomal mosaicism for a nonsense mutation (R1947X) in the NF1 gene in segmental neurofibromatosis type 1. J Invest Dermatol 2005; 125: 463–466.

Rasmussen SA, Colman SD, Ho VT, et al. Constitutional and mosaic large NF1 gene deletions in neurofibromatosis type 1. J Med Genet 1998; 35: 468–471.

Oguzkan S, Cinbis M, Ayter S, Anlar B, Aysun S . Familial segmental neurofibromatosis. J Child Neurol 2004; 19: 392–394.

Colley A, Donnai D, Evans DG . Neurofibromatosis/Noonan phenotype: a variable feature of type 1 neurofibromatosis. Clin Genet 1996; 49: 59–64.

Carey JC . Neurofibromatosis-Noonan syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1998; 75: 263–264.

Bertola DR, Pereira AC, Passetti F, et al. Neurofibromatosis-Noonan syndrome: molecular evidence of the concurrence of both disorders in a patient. Am J Med Genet A 2005; 136: 242–245.

De Luca A, Bottillo I, Sarkozy A, et al. NF1 gene mutations represent the major molecular event underlying neurofibromatosis-Noonan syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2005; 77: 1092–1101.

Huffmeier U, Zenker M, Hoyer J, Fahsold R, Rauch A . A variable combination of features of Noonan syndrome and neurofibromatosis type I are caused by mutations in the NF1 gene. Am J Med Genet A 2006; 140: 2749–2756.

Stevenson DA, Viskochil DH, Rope AF, Carey JC . Clinical and molecular aspects of an informative family with neurofibromatosis type 1 and Noonan phenotype. Clin Genet 2006; 69: 246–253.

Sarkozy A, Schirinzi A, Lepri F, et al. Clinical lumping and molecular splitting of LEOPARD and NF1/NF1-Noonan syndromes. Am J Med Genet A 2007; 143: 1009–1111.

Denayer E, de Ravel T, Legius E . Clinical and molecular aspects of RAS related disorders. J Med Genet 2008; 45: 695–703.

Brems H, Chmara M, Sahbatou M, et al. Germline loss-of-function mutations in SPRED1 cause a neurofibromatosis 1-like phenotype. Nat Genet 2007; 39: 1120–1126.

Pasmant E, Sabbagh A, Hanna N, et al. SPRED1 germline mutations caused a neurofibromatosis type 1 overlapping phenotype. J Med Genet 2009; 45: 425–430.

Spurlock G, Bennett E, Chuzhanova N, et al. SPRED1 mutations (Legius syndrome): another clinically useful genotype for dissecting the neurofibromatosis type 1 phenotype. J Med Genet 2009; 46: 431–437.

Gallinger S, Aronson M, Shayan K, et al. Gastrointestinal cancers and neurofibromatosis type 1 features in children with a germline homozygous MLH1 mutation. Gastroenterology 2004; 126: 576–585.

Raevaara TE, Gerdes AM, Lonnqvist KE, et al. HNPCC mutation MLH1 P648S makes the functional protein unstable, and homozygosity predisposes to mild neurofibromatosis type 1. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2004; 40: 261–265.

Ostergaard JR, Sunde L, Okkels H . Neurofibromatosis von Recklinghausen type I phenotype and early onset of cancers in siblings compound heterozygous for mutations in MSH6. Am J Med Genet A 2005; 139: 96–105.

Buske A, Gewies A, Lehmann R, et al. Recurrent NF1 gene mutation in a patient with oligosymptomatic neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). Am J Med Genet 1999; 86: 328–330.

Legius E, Wu R, Eyssen M, Marynen P, Fryns JP, Cassiman JJ . Encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis with a mutation in the NF1 gene. J Med Genet 1995; 32: 316–319.

Cawthon RM, Weiss R, Xu GF, et al. A major segment of the neurofibromatosis type 1 gene: cDNA sequence, genomic structure, and point mutations [published erratum in Cell 1990;62:following 608]. Cell 1990; 62: 193–201.

Wallace MR, Marchuk DA, Andersen LB, et al. Type 1 neurofibromatosis gene: identification of a large transcript disrupted in three NF1 patients [published erratum in Science 1990;250:1749]. Science 1990; 249: 181–186.

Gutmann DH, Collins FS . The neurofibromatosis type 1 gene and its protein product, neurofibromin. Neuron 1993; 10: 335–343.

Viskochil D, White R, Cawthon R . The neurofibromatosis type 1 gene. Annu Rev Neurosci 1993; 16: 183–205.

Viskochil DH The structure and function of the NF1 gene. In: Friedma Friedman JM, Gutmann DH, MacCollin M, Riccardi VM, editors. Neurofibromatosis: phenotype, natural history, and pathogenesis. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999; 119–141.

Upadhyaya M, Majounie E, Thompson P, et al. Three different pathological lesions in the NF1 gene originating de novo in a family with neurofibromatosis type 1. Hum Genet 2003; 112: 12–17.

Schmegner C, Berger A, Vogel W, Hameister H, Assum G . An isochore transition zone in the NF1 gene region is a conserved landmark of chromosome structure and function. Genomics 2005; 86: 439–445.

Hinks A, Barton A, John S, et al. Association between the PTPN22 gene and rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a UK population: further support that PTPN22 is an autoimmunity gene. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52: 1694–1699.

Eisenbarth I, Vogel G, Krone W, Vogel W, Assum G . An isochore transition in the NF1 gene region coincides with a switch in the extent of linkage disequilibrium. Am J Hum Genet 2000; 67: 873–880.

Ars E, Kruyer H, Morell M, et al. Recurrent mutations in the NF1 gene are common among neurofibromatosis type 1 patients. J Med Genet 2003; 40: e82.

Ars E, Serra E, Garcia J, et al. Mutations affecting mRNA splicing are the most common molecular defects in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Hum Mol Genet 2000; 9: 237–247.

Messiaen LM, Callens T, Mortier G, et al. Exhaustive mutation analysis of the NF1 gene allows identification of 95% of mutations and reveals a high frequency of unusual splicing defects. Hum Mutat 2000; 15: 541–555.

Gottfried ON, Viskochil DH, Fults DW, Couldwell WT . Molecular, genetic, and cellular pathogenesis of neurofibromas and surgical implications. Neurosurgery 2006; 58: 1–16.

Trovo-Marqui AB, Tajara EH . Neurofibromin: a general outlook. Clin Genet 2006; 70: 1–13.

Dilworth JT, Kraniak JM, Wojtkowiak JW, et al. Molecular targets for emerging anti-tumor therapies for neurofibromatosis type 1. Biochem Pharmacol 2006; 72: 1485–1492.

Brems H, Beert E, de Ravel T, Legius E . Mechanisms in the pathogenesis of malignant tumours in neurofibromatosis type 1. Lancet Oncol 2009; 10: 508–515.

Ismat FA, Xu J, Lu MM, Epstein JA . The neurofibromin GAP-related domain rescues endothelial but not neural crest development in Nf1 mice. J Clin Invest 2006; 116: 2378–2384.

Yohay KH . The genetic and molecular pathogenesis of NF1 and NF2. Semin Pediatr Neurol 2006; 13: 21–26.

Wimmer K, Yao S, Claes K, et al. Spectrum of single- and multiexon NF1 copy number changes in a cohort of 1,100 unselected NF1 patients. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2006; 45: 265–276.

Pros E, Gómez C, Martín T, Fábregas P, Serra E, Lázaro C . Nature and mRNA effect of 282 different NF1 point mutations: focus on splicing alterations. Hum Mutat 2008; 29: E173–E193.

Kluwe L, Siebert R, Gesk S, et al. Screening 500 unselected neurofibromatosis 1 patients for deletions of the NF1 gene. Hum Mutat 2004; 23: 111–116.

Pinson S, Creange A, Barbarot S, et al. [Neurofibromatosis 1: recommendations for management]. Arch Pediatr 2002; 9: 49–60 [ in French].

King A, Listernick R, Charrow J, Piersall L, Gutmann DH . Optic pathway gliomas in neurofibromatosis type 1: the effect of presenting symptoms on outcome. Am J Med Genet A 2003; 122: 95–99.

Thiagalingam S, Flaherty M, Billson F, North K . Neurofibromatosis type 1 and optic pathway gliomas: follow-up of 54 patients. Ophthalmology 2004; 111: 568–577.

Matsumine A, Kusuzaki K, Nakamura T, et al. Differentiation between neurofibromas and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors in neurofibromatosis 1 evaluated by MRI. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2009; 135: 891–900.

Lim R, Jaramillo D, Poussaint TY, Chang Y, Korf B . Superficial neurofibroma: a lesion with unique MRI characteristics in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005; 184: 962–968.

Cai W, Kassarjian A, Bredella MA, et al. Tumor burden in patients with neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2 and schwannomatosis: determination on whole-body MR images. Radiology 2009; 250: 665–673.

Van Meerbeeck SF, Verstraete KL, Janssens S, Mortier G . Whole body MR imaging in neurofibromatosis type 1. Eur J Radiol 2009; 69: 236–242.

Serletis D, Parkin P, Bouffet E, Shroff M, Drake JM, Rutka JT . Massive plexiform neurofibromas in childhood: natural history and management issues. J Neurosurg 2007; 106 ( suppl 5): 363–367.

Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, Moes G, Kline DG . A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg 2005; 102: 246–255.

Wise JB, Cryer JE, Belasco JB, Jacobs I, Elden L . Management of head and neck plexiform neurofibromas in pediatric patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005; 131: 712–718.

Murovic JA, Kim DH, Kline DG . Neurofibromatosis-associated nerve sheath tumors: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus 2006; 20: E1.

Fadda MT, Giustini SS, Verdino GG, et al. Role of maxillofacial surgery in patients with neurofibromatosis type I. J Craniofac Surg 2007; 18: 489–496.

Friedrich RE, Schmelzle R, Hartmann M, Fünsterer C, Mautner VF . Resection of small plexiform neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis type 1 children. World J Surg Oncol 2005; 3: 6.

Needle MN, Cnaan A, Dattilo J, Chatten J, et al. Prognostic signs in the surgical management of plexiform neurofibroma: the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia experience, 1974-1994. J Pediatr 1997; 131: 678–682.

Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Ballman K, Michels V, et al. Phase II trial of pirfenidone in adults with neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurology 2006; 67: 1860–1862.

Widemann BC, Salzer WL, Arceci RJ, et al. Phase I trial and pharmacokinetic study of the farnesyltransferase inhibitor tipifarnib in children with refractory solid tumors or neurofibromatosis type I and plexiform neurofibromas. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 507–516.

Riley J, Spiotta A, Boulis N . Experimental therapeutic approaches to peripheral nerve tumors. Neurosurg Focus 2007; 22: E2.

Baujat B, Krastinova-Lolov D, Blumen M, Baglin AC, Coquille F, Chabolle F . Radiofrequency in the treatment of craniofacial plexiform neurofibromatosis: a pilot study. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006; 117: 1261–1268.

Yoshida Y, Sato N, Furumura M, Nakayama J . Treatment of pigmented lesions of neurofibromatosis 1 with intense pulsed-radio frequency in combination with topical application of vitamin D3 ointment. J Dermatol 2007; 34: 227–230.

Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ismaili N, Bastuji-Garin S, et al. Symptoms associated with malignancy of peripheral nerve sheath tumours: a retrospective study of 69 patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Br J Dermatol 2005; 153: 79–82.

Ferner RE, Lucas JD, O'Doherty MJ, et al. Evaluation of (18)fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography ((18)FDG PET) in the detection of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours arising from within plexiform neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis 1. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000; 68: 353–357.

Friedrich RE, Kluwe L, Funsterer C, Mautner VF . Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST) in neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1): diagnostic findings on magnetic resonance images and mutation analysis of the NF1 gene. Anticancer Res 2005; 25: 1699–1702.

Bensaid B, Giammarile F, Mognetti T, et al. [Utility of 18 FDG positron emission tomography in detection of sarcomatous transformation in neurofibromatosis type 1]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2007; 134: 735–741.

Bredella MA, Torriani M, Hornicek F, et al. Value of PET in the assessment of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007; 189: 928–935.

Mautner VF, Brenner W, Fünsterer C, Hagel C, Gawad K, Friedrich RE . Clinical relevance of positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in the progression of internal plexiform neurofibroma in NF1. Anticancer Res 2007; 27: 1819–1822.

Ferner RE, Golding JF, Smith M, et al. [18F]2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) as a diagnostic tool for neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) associated malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours (MPNSTs): a long-term clinical study. Ann Oncol 2008; 19: 390–394.

Warbey VS, Ferner RE, Dunn JT, Calonje E, O'Doherty MJ . FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours in neurofibromatosis type-1. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2009; 36: 751–757.

Dalla Via P, Opocher E, Pinello ML, et al. Visual outcome of a cohort of children with neurofibromatosis type 1 and optic pathway glioma followed by a pediatric neuro-oncology program. Neuro Oncol 2007; 9: 430–437.

Lee AG . Neuroophthalmological management of optic pathway gliomas. Neurosurg Focus 2007; 23: E1.

Shen JX, Qiu GX, Wang YP, Zhao Y, Ye QB, Wu ZK . Surgical treatment of scoliosis caused by neurofibromatosis type 1. Chin Med Sci J 2005; 20: 88–92.

Tsirikos AI, Saifuddin A, Noordeen MH . Spinal deformity in neurofibromatosis type-1: diagnosis and treatment. Eur Spine J 2005; 14: 427–439.

Lazaro C, Gaona A, Lynch M, Kruyer H, Ravella A, Estivill X . Molecular characterization of the breakpoints of a 12-kb deletion in the NF1 gene in a family showing germ-line mosaicism. Am J Hum Genet 1995; 57: 1044–1049.

Vanneste E, Melotte C, Debrock S, et al. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis using fluorescent in situ hybridization for cancer predisposition syndromes caused by microdeletions. Hum Reprod 2009; 24: 1522–1528.

Spits C, De Rycke M, Van Ranst N, et al. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis for neurofibromatosis type 1. Mol Hum Reprod 2005; 11: 381–387.

Altarescu G, Brooks B, Kaplan Y, et al. Single-sperm analysis for haplotype construction of de-novo paternal mutations: application to PGD for neurofibromatosis type 1. Hum Reprod 2006; 21: 2047–2051.

Ars E, Kruyer H, Gaona A, Serra E, Lazaro C, Estivill X . Prenatal diagnosis of sporadic neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) by RNA and DNA analysis of a splicing mutation. Prenat Diagn 1999; 19: 739–742.

Origone P, Bonioli E, Panucci E, Costabel S, Ajmar F, Coviello DA . The Genoa experience of prenatal diagnosis in NF1. Prenat Diagn 2000; 20: 719–724.

Klose A, Peters H, Hoffmeyer S, et al. Two independent mutations in a family with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). Am J Med Genet 1999; 83: 6–12.

McEwing RL, Joelle R, Mohlo M, Bernard JP, Hillion Y, Ville Y . Prenatal diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1: sonographic and MRI findings. Prenat Diagn 2006; 26: 1110–1114.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jett, K., Friedman, J. Clinical and genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis 1. Genet Med 12, 1–11 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181bf15e3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181bf15e3