Abstract

Purpose: To determine the nature, sources, prevalence, and consequences of distress and burnout among genetics professionals.

Methods: Mailed survey of randomly selected clinical geneticists (MDs), genetic counselors, and genetic nurses.

Results: Two hundred and fourteen providers completed the survey (55% response rate). Eight discrete sources of distress were identified forming a valid 28-item scale (α = 0.89). The greatest sources of distress were compassion stress, the burden of professional responsibility, negative patient regard, and concerns about informational bias. Genetic counselors were significantly more likely to experience personal values conflicts, burden of professional responsibility, and concerns about informational bias than MDs or nurses. Burnout scores were lower among those practicing more than 20 years and nurses. Distress scores were positively correlated with burnout and professional dissatisfaction (P < 0.0001). Eighteen percent of respondents think about leaving patient care, and burnout was the most significant predictor. Predictors of burnout included greater distress, fewer years in practice, working in university-based settings, being a genetic counselor or an MD, and deriving less meaning from patient care.

Conclusions: Genetic service providers experience various types of distress that may be risk factors for burnout and professional dissatisfaction. Interventions to reduce distress and burnout are needed for both trainees and practitioners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The establishment of the profession of genetic counseling in the late 1960s and the recognition of the specialty of medical genetics in 1991 were both in response to burgeoning genetic knowledge and potential applications of genetics to the clinical care of patients. Despite professional recognition and technological advances, the number of physicians who seek training in medical genetics is declining, and many genetic service providers are leaving their respective professions.1–4 In partial response to the potential for serious professional shortages, efforts are being made to train nurses in genetics.5,6 In addition, primary care providers and some specialists are expected to expand their role to incorporate genetic services.7,8 The role of genetic services providers has become blurred as other providers assume some of the routine tasks previously performed by geneticists, such as pre- and posttest genetic counseling, ordering of genetic tests, and management of patients with single-gene disorders.9 This siphoning-off of routine tasks leaves the genetics provider with increasingly complex patients. Such patients are labor and time intensive, and provide the foundation for the claims that providing cognitive genetic services cannot be financially self-supporting.10–12 Reimbursement issues, lack of institutional support, low-earning potential, and uncertainty about the future of clinical genetics providers have been identified as reasons for workforce shortages.13,14 Although such external stresses encountered by genetic service providers have been acknowledged, little is known about the degree to which genetics professionals are experiencing burnout. Equally important, factors potentially contributing to burnout beyond these types of structural and professional factors have not been identified or explored. Specifically, distress encountered in the course of providing patient care may be an important contributor to burnout among genetic service providers.

One type of distress, moral distress, has been well described and investigated primarily in the nursing field.15–19 More recently, it has been acknowledged as an important issue among other types of health care providers, including physicians and pharmacists.20–23 Moral distress is the physical or emotional suffering that is experienced when constraints, either internal or external, prevent one from following the course of action that one believes is right.18 It may lead to a crisis of conscience and is associated with job dissatisfaction and attrition.18,23 Moral distress is frequently experienced in settings involving the care of critically ill patients.17,23–25

Genetic service providers also care for patients who have serious or life-threatening disorders26 and are likely to experience moral distress as well. Because of the emphasis on patient autonomy and nondirective counseling, genetic service providers also may experience moral distress when patient are making morally charged decisions, especially in prenatal genetics settings. Other characteristics of the practice of genetic medicine could lead to distress in providers. One acknowledged source of distress is uncertainty.27 In genetics, diagnosis, prognosis, and recurrence risks are frequently uncertain. In addition, dealing with unreasonable expectations of families is a recognized source of distress.28 There is evidence that there are unrealistic expectations among patients and the public regarding the application of new genetic technologies.29–31 Moreover, as the delivery of many genetic services is moving into primary care settings, the role of the geneticist is undergoing scrutiny and change. Although these are exciting times to be working in genetics, there is ambiguity about the present and future roles of genetics professionals.9 All of these characteristics might contribute to distress and burnout among genetic service providers.

There is substantial literature outside the field of genetics that addresses burnout among health care providers.28,32–39 Burnout is a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job and is characterized by exhaustion, depersonalization, and lack of personal accomplishment.40 In health care providers, the phenomenon of compassion fatigue is related to but distinct from burnout. Compassion fatigue results from the emotional and empathic engagement with clients who are experiencing distressing events, leading to the provider feeling overwhelmed by the client's suffering.41 Repeated experiences of compassion fatigue may contribute to burnout, and the burnt-out provider may be less able to manage compassion fatigue.42

Risk factors for, and the consequences of, burnout in health care providers are especially important to address because of the potentially profound impact on patients33 and the impact on the shortage of health care providers.39,43,44 In the face of increasing burnout, and changes in the health care delivery system over which clinicians have little control, greater attention needs to be paid to the causes of burnout over which clinicians might have control. Although external sources of stress—e.g., the changing medical marketplace and its impact on workload—have been widely studied and addressed, internal sources of distress have not.

Furthermore, the distress that genetics professionals may experience has only been acknowledged recently. Some limited research has documented that ethical and professional challenges frequently arise among genetic counselors,45 leading to compassion fatigue and depersonalization.42,46,47 Although some attention has been paid to these issues in genetic counselors, to date, there has been only limited research on professional satisfaction/dissatisfaction experienced by genetic service providers in general, the nature and frequency of distress they experience in their work with patients, the extent of burnout, or the degree to which distress might be a risk factor for professional dissatisfaction and burnout. Our study was designed to address this gap.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The data reported here were collected as part of a larger study of moral distress and suffering among genetics professionals. The study was reviewed and approved by a Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Data collection and analysis were conducted in three phases.

Phase 1: Item development

The development of items for the distress scale was accomplished through three focus groups of clinical genetics professionals: physicians (clinical geneticists), nurses, and genetic counselors. Focus groups were held at the 2005 annual meetings of the American Society of Human Genetics, the International Society of Nurses in Genetics, and the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC). Participants were recruited from among individuals registered to attend their professional meeting. After registrants were informed of the focus groups by letter or email, those who were interested in participating were asked to contact us. We then sent them a form asking their gender, ethnicity, years in practice, type of practice (pediatrics, adult genetics, prenatal genetics, etc.), and their availability to attend a group. The groups were scheduled during times that were convenient for the largest number of potential participants. Twenty-nine individuals participated, all were white and five were men. They had been in practice between 1 and 30 years.

The content and scope of the focus group discussion guide was informed by the literature on distress and suffering among health care practitioners, and by our own preliminary work.17 In addition, we convened a meeting of the entire study team to contribute to the development of the focus group guide. The guide was semistructured and included a brief introduction and several questions about sources and consequences of distress among genetics professionals beginning with “What clinical experiences have caused you to lose sleep at night?.”

Each focus group lasted approximately 2 hours. Participants were offered a $50 incentive for their participation and served a light meal. All groups were co-facilitated by two of the study team members. The focus group discussions were transcribed by a court stenographer. The transcripts were independently reviewed by three coinvestigators to identify the responses to the questions about the nature and sources of distress.

Phase 2: Survey development and administration

Part of the survey included a measure of distress that we developed based on data from the first phase of the study. From the focus group data, each source of distress identified by a participant was converted into a discrete item for inclusion in a questionnaire. Thirty items were identified and included in the questionnaire. We did not include items related to being overworked or underpaid. Using a 4-point Likert scale, the questionnaire asked respondents to what extent they were distressed by each source of distress. Response categories ranged from 1 = “not at all” to 4 = “a great deal.”

In addition to the items related to distress, the survey also included a measure of personal meaning in providing patient care that we developed as a part of this study.48 We also included two other measures for potential use in assessing the consequences of distress. First, we included the Maslach Burnout Inventory,49 which is a 22-item Likert scale that assesses the extent of three aspects of the burnout syndrome: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and lack of personal accomplishment. Second, we included the global measures component of the Physician Job Satisfaction scale,50 which consists of 12 items comprising three subscales (job satisfaction, career satisfaction, and specialty satisfaction). One of the items on this scale assessed thoughts about leaving patient care. The whole survey, which took approximately 20 minutes to complete, also included questions about years in practice, work setting, and demographic characteristics (gender, ethnicity, age, and marital status).

Using the mailing lists generated by the professional organizations, in 2006, 300 genetics professionals were randomly selected to receive a self-administered questionnaire. The sample comprised 100 clinical geneticists (of 1006 ABMG-certified clinical geneticists), 100 genetic counselors (of 1450 full members of NSGC), and 100 genetic nurses (of 300 members of International Society of Nurses in Genetics), excluding focus group participants. Because men are underrepresented among genetic counselors, the list of counselors was stratified by gender so that we could oversample men. The mailing contained a cover letter explaining the purpose of the study, an 8-page questionnaire, a self-addressed stamped envelope, and a $1 token of our appreciation for completing the questionnaire. Evidence indicates that even a small monetary incentive increases response rates.51 The cover page of the questionnaire asked respondents whether they (1) cared for patients within the last year (an eligibility criterion) and (2) were willing to complete the questionnaire. Respondents were instructed to return the questionnaire even if they were ineligible or unwilling to participate. One month after the initial mailing, we conducted a second mailing to another random sample of 180 potential respondents (total N = 480) to increase our sample size.

Phase 3: Statistical analysis

On receipt of all surveys, frequency distributions for all variables were examined for evidence of inconsistencies in response patterns and outliers. All continuous variables were evaluated for nonnormality using normal probability plots and measures such as skewness and kurtosis. To guard against influential data points, nonparametric statistics were used to confirm parametric results. No differences between parametric and nonparametric analyses were observed.

To develop the “clinician distress in patient care” scale, we used an exploratory factor analysis. We evaluated the frequency distributions of all items for sufficient variability and examined the mean sampling adequacy (MSA). We considered an MSA of 0.65 as a minimum requirement. An Eigen value of 1.0 was set as the minimum to extract a factor. We considered loadings of ≥0.40 to represent clear loading on a factor and values of 0.35–0.39 to represent borderline loading. For the factor analysis, we used varimax and promax rotations.

The final “clinician distress in patient care” scale consisted of 28 items comprising eight discrete subscales. The MSAs for the items ranged from 0.76 to 0.91; the overall MSA for the entire scale was 0.86. The overall α of the “clinician distress” scale was 0.89 and the α values of the subscales ranged from 0.63 to 0.90. Varimax and promax rotations yielded comparable solutions. We labeled the subscales according to the type of distress we believed was represented by the items in each factor, and they included: collegial distrust, personal values conflicts, compassion stress, negative patient regard, burden of professional responsibility, inauthenticity, concern about informational bias, and patient dread (Table 1).

Total distress and subscale scores were created by summing the Likert-scale responses to each item. Mean substitution was used when at least 75% of a subscale had valid values. In no more than 2% of any subscale was mean substitution used. We computed Pearson and Spearman correlations of distress with “meaning in providing patient care,” burnout and professional satisfaction. Associations between “distress,” “burnout,” and various demographic and practice characteristics were determined using standard bivariate analyses (Pearson correlations, t tests or analysis of variances depending on the level of measurement). For analysis of variances, we conducted multiple comparisons of groups (e.g., comparing discipline for burnout and distress) only when the overall F test was significant at 0.05. (There was one exception where the p value was borderline.) Dunnett's tests were used for multiple comparisons. Ordinary least squares regression was used to determine predictors of burnout. Logistic regression was used to determine characteristics of respondents who report “having thoughts about leaving patient care.” This is one of the items within the professional satisfaction scale that was particularly salient for this study because we only selected genetics professionals who provide patient care. SAS Version 9.1 was used for all analysis.52

RESULTS

Response rates, demographics, and practice characteristics

A total of 343 surveys were returned of the original 480 (a 71.5% return). Of these 343 returned surveys, 94 were ineligible because they did not provide patient care and 35 declined to participate. Based on 214 completed surveys, the overall survey response rate was conservatively estimated to be 55% (214 of 386: 480 − 94 ineligibles = 386 eligibles), ranging from 60% among genetic counselors to 52% among medical geneticists. This 55% response rate is almost certainly an underestimate as it assumes that the remaining 137 subjects who did not return a survey were all eligible.

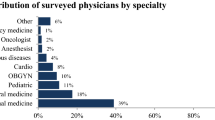

Table 2 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample, broken down by discipline. The majority of respondents were women, married, and white. Clinical geneticists and nurses were significantly older and have been in practice longer than genetic counselors. Not surprisingly, age and years in practice were highly correlated (Pearson r = 0.85, P < 0.0001). The majority of respondents reported a mixed practice of prenatal, pediatric, and adult (including cancer) patients.

Aggregate data are not available from the American Board of Medical Genetics and the International Society of Nurses in Genetics that would allow us to assess the representativeness of the clinical geneticist and nurse respondents, but some aggregate data are available from the NSGC with regard to genetic counselors.1 Although only 5% of genetic counselors are men, 14% of responding genetic counselors were men, indicating that our effort to oversample men was successful. Our sample of genetic counselors is representative of counselors overall with respect to the number in years of practice, race, and practice setting.

Prevalence of distress and burnout

The mean total distress score was 52.4 (SE = 0.84; range 31–102) of a possible high score of 112. Figure 1 demonstrates the mean distribution of scores for the overall scale and each subscale, adjusted for the number of items. For example, the distribution of scores for the 5-item “compassion stress” subscale ranges from 5 to 20. Respondents with scores of 5 experienced “no distress at all.” Respondents with scores >5 and <11 reflect those who circled “somewhat” on at least one of the items. Respondents with scores >11 experienced at least moderate distress. Based on these distributions, 32% of respondents experienced at least moderate overall distress. When broken down by subscale, the highest distress stemmed from compassion stress, the burden of professional responsibility, negative patient regard and concerns about informational bias.

Prevalence of distress. The mean distribution of scores for the overall scale and each subscale, adjusted for the number of items. For each respondent, a distress score was calculated for overall distress and each subscale by summing the numbers circled and dividing the sum by the number of items included in the subscale. Respondents classified as “not at all” were those who circled “not at all distressed” for each item included in the subscale; their mean score would be 1. Those classified as “somewhat” were those who circled “somewhat” for at least one item in the subscale and their mean scores were >1 but ≤2. Those classified as “at least moderate” had mean scores of >2.

Overall, distress scores did not vary by disciplinary background (Table 3), but subscale scores did differ by provider. Based on multiple comparisons, genetic counselors were significantly more likely than clinical geneticists to experience personal values conflicts (P = 0.017), more likely than nurses to experience the burden of professional responsibility (P = 0.038), and more likely than nurses and clinical geneticists to experience concerns about information bias (P = 0.003). Higher overall distress was associated with being woman (P < 0.006) but not with number of years in practice or percent time seeing patients (Table 4).

The mean total burnout score was 55.8 (SE = 1.10; range 22–111) of a possible high score of 154. As shown in Table 3, overall burnout was significantly lower for nurses than for clinical geneticists (P < 0.0001) or genetic counselors (P < 0.001). Emotional exhaustion was in the moderate range for all three provider types but significantly higher for clinical geneticists (P = 0.013) and genetic counselors (P < 0.0001) compared with nurses. Depersonalization was in the moderate range for genetic counselors and clinical geneticists and significantly higher compared with nurses (P < 0.0001). Scores for personal accomplishment were in the low-burnout range for all three groups but nurses reported significantly higher levels of professional accomplishment compared with clinical geneticists (P < 0.001) and genetic counselors (P < 0.0001). Professional satisfaction scores were also higher for nurses when compared with clinical geneticists (P = 0.009) and genetic counselors (P < 0.0001). Providers who work in university-based settings were more likely to report burnout than those whose practices were not based in universities (P = 0.026) (Table 4).

Relationship among distress, burnout, and professional satisfaction

As Table 5 illustrates, overall distress, and each of the subscales, was positively correlated with burnout. There was a strong negative correlation between overall distress and professional satisfaction. The subscales that were significantly inversely correlated with professional satisfaction were collegial distrust, the burden of professional responsibility, negative patient regard, and patient dread.

Within the professional satisfaction scale, 18% of respondents report that they think about leaving patient care. Genetic counselors were nearly four times more likely than nurses (53% vs. 13%; unadjusted odds ratio [OR] = 3.73; confidence interval [CI] = 1.31–10.62), and clinical genetics were two and a half times more likely than nurses (34% vs. 13%; unadjusted OR = 2.47; CI = 0.82–7.37) to report such thoughts (P = 0.036). Those who were in the top third of burnout scores were nearly five times more likely to report that they think about leaving patient care than were those in the lower third (34% vs. 14% vs. 7% for high, middle, and low tertiles; unadjusted OR = 6.80; CI = 2.40–19.22; P < 0.0001).

In a logistic regression including discipline, gender, and burnout, burnout overshadowed other characteristics as a predictor of thinking about leaving patient care.

As shown in Table 6, the most significant predictors of burnout were distress and lack of meaning derived from providing patient care. Other factors that contribute to burnout include fewer years in practice, working in university-based settings, and being a clinical geneticist or a genetic counselor when compared with a nurse. These characteristics account for roughly 37% of the variation in burnout.

DISCUSSION

Genetic service providers experience various sources of distress in the course of patient care. Among the most prevalent are compassion stress, the burden of professional responsibility, negative patient regard, inauthenticity, and concerns about informational bias. Some types of distress, including concerns about informational bias, personal values conflicts and burden of professional responsibility, may be especially pertinent to genetic counseling, and seem to be experienced more acutely by genetic counselors.53 Although the literature suggests that genetic counselors experience compassion stress and fatigue,42,47 our results indicate that compassion stress also weighs on clinical geneticists and nurses. Two of our subscales, personal values conflicts and inauthenticity, overlap with moral distress as defined in the field of nursing.15–19 However, negative patient regard, patient dread, and collegial distrust as sources of distress have received little attention in the literature. Future research is needed to determine whether these sources of distress are experienced by practitioners outside of genetics.

Overall distress was a significant risk factor for burnout and was not related to years in practice or percent time seeing patients. Previous research has documented that clinician burnout is associated with being younger54,55 and female.56 This inverse correlation between age and burnout may be reflective of a “survival bias” in which younger clinicians with higher levels of burnout are likely to leave their professions, leaving a pool of older clinicians with lower levels of burnout.40 In our study, the higher level of burnout observed in genetic counselors could be attributed to the fact that they are, in general, much younger than the physicians and nurses surveyed. Gender, however, does not seem to be associated with burnout in our sample. In fact, nurses, who are predominately woman, are less likely to report burnout. This is particularly striking given the powerful evidence of burnout among nurses more generally.36,37 Nurses in our sample were older, not generally working in critical care settings, and have made mid-career changes to specialize in genetics. This self-selected group of nurses might also be more engaged and fulfilled in their work or may have more institutional support or a lower workload. Our data suggest that nurses, in fact, experience greater professional accomplishment and overall professional satisfaction, and derive more meaning from providing patient care than clinical geneticists and genetic counselors.48 There is evidence in the literature that the establishment of fulfilling and meaningful connections with patients protects against burnout,32,39,48 and we have shown elsewhere that nurses trained in genetics are more likely than genetic counselors to report having established partnerships with their patients.57 However, even when controlling for disciplinary background and years in practice (a proxy for age), distress and lack of meaning derived from patient care are the strongest predictors of burnout in this study.

Our findings are limited by several factors. First, the items reflecting “clinician distress” were identified by focus group participants who were all white, and primarily woman. A more demographically diverse group may have identified different sources of distress. Moreover, because nurses and genetic counselors are predominantly women, gender and discipline are highly confounded and should be disentangled in future research. Second, because the majority of respondents reported a mixed practice of prenatal, pediatric, and adult patients, we were unable to determine whether experiences with a particular type of patient were related to distress or burnout. A larger sample size including more providers seeing only one type of patient would have allowed us to examine these variables by patient type. Third, the response rate for clinical geneticists and nurses was not as high as we had hoped. Because we were unable to obtain aggregate information to determine the representativeness of those samples, we do not know whether respondents differed from nonrespondents in meaningful ways. Fourth, we did not assess the prevalence and impact of external sources of stress that are associated with burnout—e.g., being overworked, underpaid, and lacking resources—because they are likely to be relevant in all clinical settings and we wanted to see what sources of distress might be particular to the genetics context. Moreover, we were particularly interested in focusing on internal sources of distress because less is understood about them than about external sources of stress. Nevertheless, by omitting external sources of stress from our survey, we were unable to determine the extent to which they are related to burnout and professional dissatisfaction among genetics professionals. We were also unable to assess cause and effect in that it could not be determined whether burnout leads to increased perceptions of distress, or whether the experience of distress leads to burnout.47

Despite these limitations, we believe our findings represent an important and valid contribution to the literature for several reasons. Ours is the first study to describe and quantify various sources of distress and levels of burnout among genetics professionals. Second, although most of the literature on burnout and professional satisfaction has focused on a single discipline (medicine, nursing, or genetic counseling), our findings suggest that “clinician distress in patient care” crosses disciplinary lines. Finally, our results provide strong evidence that “clinician distress in patient care” is related to burnout, which, in turn, contributes to thoughts about leaving patient care. To meet the growing service needs that are likely to result from advances in molecular genetics, efforts should be made to monitor for distress, particularly among genetic counselors, university-based providers, and those who are relatively new to the field.

We are currently analyzing data from interviews and follow-up focus groups we conducted with genetic service providers to develop recommendations for addressing distress. Although extensive recommendations for clinical practice, training, and future research will be forthcoming, based on the survey results reported here, some preliminary recommendations can be made.

First, distress experienced by genetic service providers must be acknowledged. Self-monitoring, reflection, and discussion of the situation with either a trusted colleague, or in a formal or informal group setting had been advocated for physicians25 and nurses in general,17 as well as for genetic counselors.47 Based on our finding that collegial distrust can be a source of distress, group interventions to address distress and burnout may be most effective by including all members of the genetics team. Such mixed support groups could address all types of distress identified in this study while simultaneously encouraging communication, trust, and support among team members.

Second, we show here that increased “personal meaning in patient care” is inversely related to distress and burnout. Increased meaning may be derived by forming strong connections with patients. Such connections are fostered through bearing witness, which has been described by Naef58 as a fundamental process of “being there and being with, listening and attending to, and staying with persons as they live situations of health and illness, shape their quality of life, search for meaning, struggle to make difficult choices, and experience intense moments of recognition, fear, joy, and sorrow.” If genetic service providers were to acknowledge that bearing witness was central to their work with patients, we believe that some of the distress experienced, especially that related to the burden of professional responsibility, patient dread, and concerns about informational bias would decrease. Unfortunately, the current emphasis in clinical genetics and genetic counseling on factual information, patient education, and patient autonomy may interfere with the provider's ability to form a strong partnership with patients.

Programs that train genetics professionals should consider addressing distress and burnout overtly as part of their curricula. Some of the interventions that are being developed and implemented outside of genetics59–63 may be useful models for preventing or reducing distress and burnout among trainees and practitioners in genetics.

REFERENCES

National Society of Genetic Counselors National Society of Genetic Counselors Professional Status Survey 2006. National Society of Genetic Counselors Chicago, IL.

Cooksey JA, Forte G, Flanagan PA, Benkendorf J, Blitzer MG . The medical genetics workforce: an analysis of clinical geneticist subgroups. Genet Med 2006; 8: 603–614.

Evans JP . A future for medical genetics: lessons from Catch 22. Genet Med 2007; 9: 1–3.

Korf BR, Feldman G, Wiesner GL . Report of Banbury Summit meeting on training of physicians in medical genetics, October 20–22, 2004. Genet Med 2005; 7: 433–438.

Olsen SJ, Feetham SL, Jenkins J, et al. Creating a nursing vision for leadership in genetics. Medsurg Nurs 2003; 12: 177–183.

Kirk M, Tonkin E, Burke S . Engaging nurses in genetics: the strategic approach of the NHS National Genetics Education and Development Centre. J Genet Couns 2008; 17: 180–188.

Guttmacher AE, Jenkins J, Uhlmann WR . Genomic medicine: who will practice it? A call to open arms. Am J Med Genet 2001; 106: 216–222.

Greendale K, Pyeritz RE . Empowering primary care health professionals in medical genetics: how soon? How fast? How far?. Am J Med Genet 2001; 106: 223–232.

Epstein CJ . Medical genetics in the genomic medicine of the 21st century. Am J Hum Genet 2006; 79: 434–438.

Bernhardt BA, Pyeritz RE . The economics of clinical genetics services. III. Cognitive genetics services are not self-supporting. Am J Hum Genet 1989; 44: 288–293.

McPherson E, Zaleski C, Benisek k . Clinical genetics provider real-time workflow study. Genet Med 2008; 10: 699–706.

Li C . Letter to the editor: clinical genetics provider real-time workflow study. Genet Med 2008; 10: 915.

Korf BR . Genetics in medical practice. Genet Med 2002; 4: 10S–14S.

Pletcher BA, Jewett EAB, Cull WL, et al. The practice of clinical genetics: a survey of practitioners. Genet Med 2002; 4: 142–149.

Corley MC, Minick P, Elswick RK, Jacobs M . Nurse Moral Distress and Ethical Work Environment. Nurs Ethics 2005; 12: 381–390.

Corley MC . Nurse moral distress: a proposed theory and research agenda. Nurs Ethics 2002; 9: 636–650.

Rushton CH . Defining and addressing moral distress: tools for critical care nursing leaders. AACN Adv Crit Care 2006; 17: 161–168.

Pendry P . Moral distress: recognizing it to retain nurses. Nurs Econ 2007; 25: 217–221.

Sudin-Huard D, Fahy K . Moral distress, advocacy and burnout: theorizing the relationships. Intl J Nurs Pract 1999; 5: 8–13.

Sporrong SK, Hoglund AT, Arnetz B . Measuring moral distress in pharmacy and clinical practice. Nurs Ethics 2006; 13: 416–427.

Austin WJ, Kagan L, Rankel M, Bergum V . The balancing act: psychiatrists' experience of moral distress. Med Health Care Philos 2008; 11: 89–97.

Devictor D, Carnevale F . Improving end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Therapy 2008; 5: 387–390.

Hamric AB, Blackhall LJ . Nurse-physician perspectives on the care of dying patients in intensive care units: collaboration, moral distress, and ethical climate. Crit Care Med 2007; 35: 422–429.

Janvier A, Nadeau S, Deschenes M, Couture E, Barrington KJ . Moral distress in the neonatal intensive care unit: caregiver's experience. J Perinat 2007; 27: 203–208.

Meier DE, Back AL, Morrison RS . The inner life of physicians and care of the seriously ill. JAMA 2001; 286: 3007–3014.

Knebel AR, Hudgings C . End-of-life issues in genetic disorders: summary of workshop held at the National Institutes of Health on September 26, 2001. Genet Med 2002; 4: 373–378.

French SE, Lenton R, Walters V, Eyles J . An empirical evaluation of an expanded Nursing Stress Scale. J Nurs Meas 2000; 8: 161–178.

Maytum JC, Heiman MB, Garwick AW . Compassion fatigue and burnout in nurses who work with children with chronic conditions and their families. J Ped Health Care 2004; 18: 171–179.

Tambor ES, Bernhardt BA, Rodgers J, Holtzman NA, Geller G . Mapping the human genome: an assessment of media coverage and public reaction. Genet Med 2002; 4: 31–36.

Rose A, Peters N, Shea JA, Armstrong K . The association between knowledge and attitudes about genetic testing for cancer risk in the United States. J Health Comm 2005; 10: 309–321.

Bates BR, Lynch JA, Bevan JL, Condit CM . Warranted concerns, warranted outlooks: a focus group study of public understandings of genetic research. Soc Sci Med 2005; 60: 331–344.

Chopra SS, Sotile WM, Sotile MO . Physician burnout. JAMA 2004; 291: 633.

Gunderson L . Physician burnout. Ann Intern Med 2001; 135: 145–148.

Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL . Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med 2002; 136: 358–367.

Thomas NK . Resident burnout. JAMA 2004; 292: 2880–2889.

Roach BL . Burnout and the nursing profession. Health Care Superv 1994; 12: 41–47.

Meltzner LS, Huckaby LM . Critical care nurses' perceptions of futile care and its effect on burnout. Am J Crit Care 2004; 13: 202–208.

Oehler JM, Davidson MG . Job stress and burnout in acute and nonacute pediatric nurses. Am J Crit Care 1992; 2: 81–90.

Coomber B, Barriball LK . Impact of job satisfaction components on intent to leave and turnover for hospital-based nurses: a review of the research literature. Int J Nurs Stud 2007; 44: 297–314.

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP . Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol 2001; 52: 397–422.

Figley CR . Compassion fatigue: psychotherapists' chronic lack of self care. J Clin Psychol 2002; 58: 1433–1441.

Benoit LG, Veach PC, LeRoy BS . When you care enough to do your very best: genetic counselor experiences of compassion fatigue. J Genet Couns 2007; 16: 299–312.

Ulrich C, O'Donnell P, Taylor C, Farrar A, Danis M, Grady C . Ethical climate, ethics stress, and job satisfaction of nurses and social workers in the United States. Soc Sci Med 2007; 65: 1708–1719.

Okie S . Innovation in primary care—staying one step ahead of burnout. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 2305–2309.

Veach PM, Bartels DM, LeRoy BS . Ethical and professional challenges posed by patients with genetic concerns: a report of focus group discussions with genetic counselors, physician and nurses. J Genet Couns 2001; 10: 97–119.

Dexter N, Shannon KM, Wangh SK, Rintell D . Burnout in genetic counselors. J Genet Couns 2003; 12: 563–564.

Udipi S, Veach PM, Kao J, LeRoy BS . The psychic costs of empathic engagement: personal and demographic predictors of genetic counselor compassion fatigue. J Genet Counsel 2008; 17: 459–471.

Geller G, Bernhardt BA, Rushton CH, Carrese J, Kolodner K . What do clinicians derive from partnering with their patients? A reliable and valid measure of “personal meaning in patient care.”. Patient Educ Couns 2008; 72: 293–300.

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP . Maslach burnout inventory manual, 3rd ed. Palo Alto Consulting Psychologists Press 1996.

Williams ES, Konrad TR, Linzer M, et al. for the SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group Refining the measurement of physician job satisfaction: results from the Physician Worklife Survey. Med Care 1999; 37: 1140–1154.

Tambor ES, Chase GA, Faden RR, Geller G, Hofman KJ, Holtzman NA . Improving response rates through incentive and follow-up: the effect on a survey of physicians' knowledge of genetics. Am J Public Health 1993; 83: 1599–603.

SAS Institute Inc SAS Version 9.1.8.2. Cary, NC SAS Institute Inc 2006;

Geller G, Micco E, Silver RJ, Kolodner K, Bernhardt BA . The role and impact of personal faith and religion among genetic service providers. Am J Med Genet Part C Semin Med Genet 2009; 151C: 31–40.

Freeborn DK . Satisfaction, commitment and psychological well-being among HMO physicians. West J Med 2001; 174: 13–18.

Campbell DA, Sonnad SS, Eckhouser FE . Burnout among American surgeons. Surgery 2001; 130: 696–705.

McMurray JE, Linzer M, Konrad TR, Douglas J, Shugerman R, Nelson K . The work lives of women physicians. J Gen Intern Med 2000; 15: 372–380.

Bernhardt BA, Geller G, Doksum T, Metz SA . Evaluation of nurses and genetic counselors as providers of education about breast cancer susceptibility testing. Oncol Nurs Forum 2000; 27: 33–39.

Naef R . Bearing witness: a moral way of engaging in the nurse-person relationship. Nurs Philos 2006; 7: 146–156.

Hatem CJ . Renewal in the practice of medicine. Patient Educ Couns 2006; 62: 299–301.

Shanafelt TD . Finding meaning, balance, and personal satisfaction in the practice of oncology. J Support Oncol 2005; 3: 157–164.

Fillion L, Dupuis R, Tremblay I, DeGrace GR, Greitbart W . Enhancing meaning in palliative care practice: a meaning-centered intervention to promote job satisfaction. Palliat Support Care 2006; 4: 333–344.

Meadors P, Lamson A . Compassion fatigue and secondary traumatization: provider self care on intensive care units for children. J Pediatr Health Care 2008; 22: 24–34.

Edward KL, Hercelinskyj G . Burnout in the caring nurse: learning resilient behaviours. Br J Nurs 2007; 16: 240–242.

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by Grant no. 5R01HG3004-2 from the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI). The authors thank the genetics professionals who participated in our focus groups and responded to our survey. They also appreciate the contributions of the other members of our study team, and the logistical assistance of the leadership of the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC), the International Society of Nurses in Genetics (ISONG), the American Board of Medical Genetics (ABMG) and the American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG). Preliminary findings were presented at the 2006 Annual Meeting of the American Society for Bioethics & Humanities (ASBH) in Denver, the 2006 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Communication in Health care (AACH) in Atlanta, and the 2007 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG) in San Diego.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bernhardt, B., Rushton, C., Carrese, J. et al. Distress and burnout among genetic service providers. Genet Med 11, 527–535 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181a6a1c2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181a6a1c2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

More than an information service: are counselling skills needed by genetics professionals in the genomic era?

European Journal of Human Genetics (2018)

-

Mindfulness Among Genetic Counselors Is Associated with Increased Empathy and Work Engagement and Decreased Burnout and Compassion Fatigue

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2018)

-

National Society Of Genetic Counselors Natalie Weissberger Paul National Leadership Award Address: “Patients and Research: Paths to Personal and Professional Growth”

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2016)

-

The Relationship Between Burnout and Occupational Stress in Genetic Counselors

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2016)

-

The Relationship between the Supervision Role and Compassion Fatigue and Burnout in Genetic Counseling

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2016)