Abstract

Purpose

Abortive cryptophthalmos is a rare congenital eyelid anomaly with poor prognosis for vision and cosmesis. The study aims to present its varied manifestations and surgical outcomes.

Patients and methods

The medical records of patients with abortive cryptophthalmos treated at the Oculoplastic Clinic of Beijing Tongren Hospital between January 2004 and May 2016 were reviewed. Early surgical intervention was performed when exposure keratopathy occurs. Upper eyelid and superior fornix were mainly reconstructed with sliding myocutaneous flap and scleral and amniotic grafts. Post-operative upper eyelid contour, recurrence of symblepharon, and ability to retain prosthesis were evaluated.

Results

The study included 41 eyes of 28 patients. The median age at first presentation was 5 years (ranging from 1 month to 58 years). The majority (79%) with concurrent craniofacial abnormalities tended to be associated with more severe cryptophthalmos. Nine eyes of 9 patients had recurrence of symblepharon. Acceptable functional and cosmetic outcomes were achieved in 20 of the 24 patients receiving repair procedures during the follow-up period.

Conclusion

One-stage reconstruction of eyelid and fornix with scleral and amniotic grafts is an effective strategy to correct abortive cryptophthalmos.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

First described by Zehender in 1872, cryptophthalmos is a rare congenital eyelid malformation. The deformity can be classified into three types: complete, incomplete, and abortive. The complete form is characterized by skin of the forehead extending in continuity with the cheek over the globe without differentiation of eyelids. In the incomplete form, an incomplete skin fold covers the medial aspect of the palpebral aperture with the lateral eyelid structures being present. The abortive variant, also referred to congenital symblepharon, is manifested as the deficient medial upper eyelid fused to the superior aspect of the globe with superior fornix abnormal. Among them, abortive cryptophthalmos is potentially vision-threatening because of exposure keratopathy resulting from upper eyelid coloboma and limited motility of the globe. It should be closely monitored and promptly treated if corneal exposure occurs, especially in children.1, 2

Surgical rehabilitation of abortive cryptophthalmos presents major challenges for oculoplastic surgeons. The main objective is to reconstruct both upper eyelid and superior fornix. The current study summarizes our experience in the clinical observations and management of this congenital deformity over a period of 12 years.

Materials and methods

The medical records of patients with abortive cryptophthalmos who were referred to Beijing Tongren Hospital between January 2004 and May 2016 were reviewed. All cases were examined and managed by the same senior surgeon (DL). Collected data included the age at presentation, gender, consanguinity, family history, clinical presentations, surgical interventions, and outcomes. There was no attempt to separate syndromic and nonsyndromic cases in this study. The affected eyes were categorized into mild, moderate, and severe grades, based on the size of upper eyelid coloboma, severity of symblepharon, and extent of keratinization of cornea (Figure 1).1 Exposure keratopathy was an indication for immediate surgery in all cases. For severe abortive cryptophthalmos without visual potential, cosmesis was the primary goal and intervention was delayed until there was enough tissue for reconstruction.

The study adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects and was approved by the ethics committee of Beijing Tongren Hospital. All the patients or guardians gave their informed consent prior to inclusion in the study. Permission was obtained for publication of identifiable patient photos.

Surgical technique

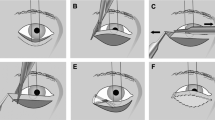

All procedures were performed under local or general anesthesia. The procedure was initiated by symblepharon release. Careful dissection was made from 0.5 mm beyond the head of cutaneous pterygium to the superior fornix. Lateral bulbar conjunctival flap was transposed to the defective palpebral and forniceal conjunctiva. For moderate and severe congenital symblepharon or recurrent cases, inferior bulbar conjunctival transposition flap was used. A layer of amniotic membrane was then applied to cover the exposed episclera and denuded cornea. Simultaneously, the upper eyelid was reconstructed in layers depending on the size of defect. The edges of the defect were refreshed and gray-line split was made. The posterior lamella was repaired with sliding tarsoconjunctival flap or banked sclera and conjunctival flap, and the anterior lamella with superonasal sliding myocutaneous flap (Figure 2). In cases with excessive dissection, a symblepharon ring was placed to prevent post-operative scarring and fibrosis for at least 2 months. Finally, temporary tarsorrhaphy was made for only 1–2 weeks in mild cases or younger patients with visual potential, while permanent tarsorrhaphy for 2 months in severe cases.

One-stage reconstruction of upper eyelid and superior fornix. (a) Lateral conjunctival flap was translocated to repair the deficient forniceal conjunctiva. (b) Amniotic membrane was used to cover the exposed episclera and denuded cornea. (c) The tarsal plate was reconstructed with a scleral graft. (d) The anterior lamellar of the eyelid was repaired with superonasal sliding myocutaneous flap.

Postoperatively, the antibiotic–steroid drops and ointment were used for 3 weeks. For eyes without visual potential, an esthetic prosthesis was fitted. Patients were followed up at regular intervals with the assessment of the post-operative cosmetic and functional outcomes. Failure was defined as recurrence of symblepharon or shallow fornix with difficulty to retain prosthesis.

Results

A total of 41 eyes of 28 patients with abortive cryptophthalmos were identified (Table 1). It was more common in males than females (17 : 11). All the patients except one received surgical treatment. The median age at first presentation was 5 years (range, 1 month–58 years). Among them, three patients had previous history of relevant surgeries. Four patients (14%) had a history of maternal exposure to upper respiratory tract infection or prescription drugs (three patients), and nitrogen oxide (one patient) during early pregnancy. Parental consanguinity was present in only one case with first-cousin marriage. There was a female patient with abortive cryptophthalmos on one side and complete variant on the fellow side whose sister had bilateral complete cryptophthalmos.

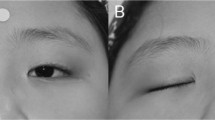

Fifteen out of 28 (54%) cases were unilateral and 13 were bilateral (46%). The majority was moderately cryptophthalmic (24 eyes, 59%). Cryptophthalmos was an isolated finding in 4 patients (14%) and associated with other developmental anomalies in over four-fifth of patients. Four patients (14%) had concurrent ocular abnormalities, including three with choristomas, one with microphthalmia, and one with microcornea. In 22 patients (79%) who had associated craniofacial and systemic abnormalities, eyebrow alopecia, aberrant anterior hairlines, and bifid nose or elevation of the alar base were most common, affecting 75%, 54%, and 36%, respectively (Figure 2). Individual cases of hydrocephalus and unilateral renal agenesis were also noted.

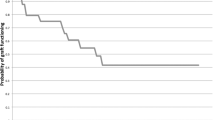

One patient was lost to follow-up after initial examination and three patients lost after first surgery. During a follow-up period varying from 4 months to 11 years, 20 of the remaining 24 patients undergoing surgery had acceptable cosmetic results with good eyelid closure and no corneal exposure (Figure 3). Nine eyes of 9 patients received repeated procedures due to recurrence. The corneopalpebral adhesions recurred in exactly the same area where they were initially observed. Only one patient was fitted with ocular prosthesis.

Discussion

Cryptophthalmos may be unilateral or bilateral, and may exist exclusively or in conjunction with varied facial and systemic deformities. Tessier considers eyelid coloboma as a form of facial clefting disorder, which includes adhesions between the cleft and globe, eyebrow alopecia, nasal hypoplasia, and disturbance of the anterior hairlines.3, 4 In our cases of abortive variant, no laterality was seen and males outweighed females. The majority had co-existing craniofacial deformities, which tended to be associated with more severe cryptophthalmos. It is noteworthy that cryptophthalmos with other malformations should differentiate with Fraser syndrome. Two major criteria and one minor criterion, or one major and at least four minor criteria were required for the diagnosis of Fraser syndrome. Major diagnostic criteria include cryptophthalmos, syndactyly, abnormal genitalia, and sib with Fraser syndrome. Minor criteria involve a series of malformations of nose, ears, larynx, and renal agenesis, and so on.5

Embryologically, the upper lid fold is derived from medial and lateral protuberances of the frontonasal process and the lower lid fold from the maxillary process. Disruption of proper development of the frontonasal and maxillary processes not only results in eyelid malformation, but also in other craniofacial and ocular abnormalities.3 The exact causes of abortive cryptophthalmos still remain unresolved. In this series, a positive history of virus infection, drug or toxic gas exposure during early pregnancy was revealed in four mothers. Two patients had a positive family history, one with parental consanguinity, and the other with affected sibling. Both exogenous and genetic factors are likely involved in the etiology of abortive cryptophthalmos.

The indication for early surgical intervention is to protect the cornea and optimize any visual potential the cryptophthalmic eye may have. The challenge is often compounded by the lack of tissue laxity in children and the risk of inducing iatrogenic amblyopia due to occlusion of the visual axis. It is recommended that surgical repair of the eyelid coloboma be delayed until the age of 3–6 months if possible.6 Generally, a separate or combined two-stage reconstruction of eyelid and fornix is required. Most surgeons prefer eyelid-sharing techniques like Cutler–Beard or Mustardé switch flap to reconstruct the eyelid. Nevertheless, these procedures may not only significantly affect the visual prognosis because of long-term closure of the visual axis, but also cause scar retraction and distortion of the donor lower eyelid.4, 7 Various materials have been used to reconstruct the fornix, including oral mucous membrane, autologous conjunctiva, and amniotic membrane. It is reported that amniotic membrane was superior to buccal mucous membrane and hard palate in the maintenance of the fornix in cryptophthalmic repair.8 The major advantage is the ability to reduce inflammation and scarring while promoting epithelization.9, 10 We employed banked sclera and sliding flap to reconstruct the upper eyelid and meanwhile autologous conjunctiva and amniotic membrane to reconstruct the fornix. Satisfactory cosmetic and functional results were achieved in most cases.

On the basis of our limited experience, recurrence of symblepharon is comparatively common after surgery in abortive cryptophthalmos. From an embryologic point of view, eyelid fusion is critical for corneal development. The cornea will be exposed to amniotic fluid and become abnormal if there is no eyelid fusion resulting from coloboma. Histopathologically, the corneal epithelium underlying coloboma displayed epidermidalization with rete peg formation and hyperkeratosis.1 It can be explained why the corneopalpebral adhesions tend to recur in exactly the same area where they were observed at the first presentation.11 More effective strategy is required to prevent the recurrence of symblepharon.

For abortive cryptophthalmos, rehabilitation is extremely challenging and the prognosis for useful vision mainly depends on the extent of the ocular anomalies and the visual potential. Early surgical intervention should be considered when there is a high risk of corneal exposure. One-stage reconstruction of upper eyelid and superior fornix with scleral and amniotic grafts can achieve satisfactory results.

References

Subramanian N, Iyer G, Srinivasan B . Cryptophthalmos: reconstructive techniques-expanded classification of congenital symblepharon variant. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2013; 29: 243–248.

Saleh GM, Hussain B, Verity DH, Collin JR . A surgical strategy for the correction of Fraser syndrome cryptophthalmos. Ophthalmology 2009; 116: 1707–1712.

Smith HB, Verity DH, Collin JRO . The incidence, embryology, and oculofacial abnormalities associated with eyelid colobomas. Eye (lond) 2015; 29: 492–498.

Seah LL, Choo CT, Fong KS . Congenital upper lid colobomas: management and visual outcome. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2002; 18: 190–195.

Slavotinek AM, Tifft CJ . Fraser syndrome and cryptophthalmos: review of the diagnostic criteria and evidence for phenotypic modules in complex malformation syndromes. J Med Genet 2002; 39: 623–633.

Grover AK, Chaudhuri Z, Malik S, Bageja S, Menon V . Congenital eyelid colobomas in 51 patients. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2009; 46: 151–159.

Fan X, Shao C, Fu Y, Zhou H, Lin M, Zhu H . Surgical management and outcome of Tessier number 10 clefts. Ophthalmology 2008; 115: 2290–2294.

Stewart JM, David S, Seiff SR . Amniotic membrane graft in the surgical management of cryptophthalmos. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2002; 18: 378–380.

Fung AT, Martin P, Petsoglou C, Kourt G . Repair of isolated abortive cryptophthalmos with lower eyelid switch flap and amniotic membrane graft. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2009; 25: 158–161.

Maharajan VS, Shanmuganathan V, Currie A, Hopkinson A, Powell-Richards A, Dua HS . Amniotic membrane transplantation for ocular surface reconstruction: indications and outcomes. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2007; 35: 140–147.

Tawfik HA, Abdulhafez MH, Fouad YA . Congenital upper eyelid coloboma: embryologic, nomenclatorial, nosologic, etiologic, pathogenetic, epidemiologic, clinical, and management perspectives. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2015; 31: 1–12.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, J., Hou, Z., Li, Y. et al. Eyelid and fornix reconstruction in abortive cryptophthalmos: a single-center experience over 12 years. Eye 31, 1576–1581 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2017.94

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2017.94

This article is cited by

-

Reconstruction strategy in isolated complete Cryptophthalmos: a case series

BMC Ophthalmology (2019)