Abstract

Purpose

To determine safety and efficacy of intravitreal high-dose ranibizumab in the treatment of active neovascular polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV).

Methods

In this Phase I/II, single-center, randomized, controlled, double-masked study, predominantly non-Asian, previously treated or treatment-naive, male and female adult patients were randomized to receive high-dose (1.0/0.1 ml or 2.0 mg/0.05 ml; n=15) or standard-dose (0.5 mg/0.05 ml; n=5) ranibizumab in 3 monthly loading doses, followed by 9 months of criteria-based, as-needed retreatment. Safety was evaluated by a descriptive analysis of all non-serious and serious adverse events, angiographic assessments, physical examinations, vital signs, ocular examinations, and visual acuity measurements. Visual acuity and anatomic outcomes are described for the high-dose group.

Results

Twenty patients (aged 35–76 years; 8 Black, 11 White, 1 Asian) were enrolled. At baseline, in the high-dose group, mean best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 63.5 letters (Snellen equivalent ~20/50), and mean baseline central foveal thickness (CFT) was 253.7 μm. High-dose ranibizumab was generally well tolerated without evidence of ocular or systemic severe adverse events, including arterial thromboembolic events. At month 12, in the high-dose group, the mean overall change from baseline in BCVA was +6.7 letters and in CFT was −49.7 μm.

Conclusion

High-dose ranibizumab monotherapy is safe and efficacious for treating patients with PCV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV) is a type of exudative maculopathy characterized by the presence of focal nodular areas of hyperfluorescence developing from the choroidal circulation within the initial 6 min after indocyanine green (ICG) injection, with or without an associated branching vascular network.1 Orange–red subretinal nodules seen with ICG hyperfluorescence are indicative of PCV.

Evidence has shown that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is expressed in PCV lesions2, 3; thus, anti-VEGF monotherapy has been evaluated for the treatment of PCV.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 In a previous study7 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00837330), we evaluated intravitreal ranibizumab 0.3- and 0.5-mg monotherapy in 20 eyes of non-Asian patients with PCV. Ranibizumab (0.3- and 0.5-mg groups pooled) was well tolerated and resulted in improved best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA; +1.2 Snellen lines at months 12 and 24) and reduced center point thickness (−53 and −67 μm at months 12 and 24, respectively) in the majority of eyes.

Combination anti-VEGF and photodynamic therapy (PDT) has been evaluated in both Asian15, 16, 17, 18, 19 and White20 patients with PCV, with no clear consensus on the superiority of PDT or combination therapy. Most of these studies were conducted in predominantly Asian populations. Comparisons have shown that the incidence and demographic features of PCV vary across different ethnic groups.21 Black and Asian patients are most at risk for PCV; however, 8–13% of White patients with exudative age-related macular degeneration (AMD) have also exhibited PCV.22, 23 Data are needed on baseline characteristics associated with better treatment response in non-Asian PCV patients.

In this study, the aim was to determine if anti-VEGF monotherapy would be adequate treatment, particularly in non-Asian patients. Mixed results have been observed regarding the effect of standard doses of anti-VEGF monotherapy on polyp regression, despite improvement in visual acuity.15, 24, 25, 26 In the EVEREST study (N=61),15 complete polyp regression at month 6 was seen in only 28.6% of patients treated with ranibizumab 0.5-mg monotherapy. Also, studies demonstrated that PCV compared with typical neovascular AMD may be more resistant to anti-VEGF therapy.25, 26

Information on the use of higher doses of ranibizumab for the treatment of PCV is limited, particularly in eyes of non-Asian patients. Although ranibizumab 2.0 mg did not show increased efficacy compared with ranibizumab 0.5 mg for the treatment of neovascular AMD in the HARBOR study,27, 28 the recalcitrant nature of PCV lesions provides a rationale for studying high-dose ranibizumab in PCV patients. The objective of this study was to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of high-dose ranibizumab (1.0 or 2.0 mg) monotherapy in previously treated and treatment-naive, predominantly non-Asian patients with exudative PCV.

Materials and methods

Study design

In this Phase I/II, single-center, randomized, controlled, double-masked study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01469156), patients with exudative PCV received intravitreal standard-dose (0.5 mg) or high-dose (1.0 or 2.0 mg) ranibizumab (Genentech, Inc., South San Francisco, CA, USA). The original study protocol planned to assess ranibizumab 2.0 mg/0.05 ml in the high-dose group. However, after the HARBOR study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00891735) demonstrated no increased efficacy of the 2.0-mg dose compared with the 0.5-mg dose for neovascular AMD,27, 28 the 2.0-mg dose was no longer manufactured. Seven of 15 eyes in the high-dose group initially received ranibizumab 2.0 mg/0.05 ml (one to four doses); however, an amendment was made mid-trial to adjust the high dose from 2.0 mg/0.05 ml to 1.0 mg/0.1 ml. Thereafter, all 15 patients received ranibizumab 1.0-mg doses. Patients who received 1.0- and 2.0-mg doses of ranibizumab were pooled and considered as the high-dose group and compared with the standard-dose group for analyses. This study and the protocol amendment were approved by an institutional review board, and written informed consent was obtained from patients prior to study participation. We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during this research.

Patient selection

Twenty consecutive male or female adults aged >18 years with PCV were eligible for enrollment. PCV was defined as choroidal neovascularization (CNV) with occult characteristics on fluorescein angiography (FA) with saccular dilatations and polypoidal interconnecting vascular channels on indocyanine green angiography and/or FA. Additional inclusion criteria were BCVA between 20/20 and 20/800 (Snellen equivalent) as measured by Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) charts at 4 m; leaking lesions consistent with PCV; no non-foveal laser, PDT, intravitreal steroids, transpupillary thermotherapy, radiotherapy, anti-VEGF therapy, or intraocular surgery within the past 30 days; and clear ocular media to photography/angiography. Exclusion criteria consisted of patients with allergy to fluorescein, ICG, iodine, or shellfish; pregnancy; AMD; advanced glaucoma; history of previous subfoveal laser; participation in simultaneous clinical trial; or any conditions that would pose a significant hazard to the subject if investigational therapy was initiated or would interfere with disease status or with study participation.

Treatment

Patients were randomized (3 : 1) at the time of the screening visit to receive high-dose (1.0 mg/0.1 ml or 2.0 mg/0.05 ml) or standard-dose (0.5 mg/0.05 ml) ranibizumab in three monthly loading doses, followed by a 9-month period of criteria-based, as-needed retreatment. As-needed ranibizumab retreatment was permitted if a patient had: (1) a ≥5-letter loss from the previous visit if associated with disease activity (eg, intraretinal edema, subretinal fluid, pigment epithelial detachment with fluid, and so on.) on optical coherence tomography (OCT); (2) a ≥50-μm increase in OCT central subfield thickness from the previous visit; or (3) persistent disease activity on OCT and/or clinical evidence of retinal/subretinal hemorrhage secondary to PCV.

Alternative rescue therapies (eg, PDT, laser, or steroids) were permitted per investigator discretion with guidelines for rescue therapy: (1) a ≥10-letter loss from baseline or a previous visit; (2) two consecutive ranibizumab injections were administered 1 and 2 months prior; and (3) persistent disease activity on OCT. PDT or laser rescue therapy was possible if the above guidelines were met and if well-defined hyperfluorescence on FA or ICG was deemed responsive to such therapy by the investigator. The study coordinator prepared doses and was unmasked as was the injecting investigator (HS); patients and the examining investigator (DMM) were masked to the dose.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was incidence and severity of ocular and systemic adverse events (AEs) over the course of 12 months. AEs were documented and assessed by the principal investigator. Secondary outcomes included BCVA and anatomic end points measured by OCT, fluorescein and indocyanine green angiography, and fundus photographs.

BCVA end points included mean and median change in BCVA and proportion of patients with a change of ±5, 10 and 15 ETDRS letters from baseline at months 3, 6, 9, and 12.

Spectral-domain OCT (Zeiss Cirrus (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA), models 4000 and 5000, for OCT thickness and macular volume; Spectralis (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) for choroidal thickness) was performed monthly over 12 months to assess mean changes in central foveal thickness (CFT) and macular volume from baseline over time up to month 12. Additional assessments included the proportion of patients with no OCT evidence of intraretinal or subretinal fluid from CNV at month 12 and choroidal thickness at months 3 and 12. Choroidal thickness was measured by enhanced depth imaging-OCT.29 Measurements were taken at the fovea and at locations 1.5-mm temporal, nasal, superior, and inferior to the center of the fovea.

Fluorescein and ICG angiograms and fundus photographs were mandatory at baseline and at months 3, 6, 9 and 12. Assessments included mean changes in total area of FA CNV leakage and ICG CNV lesion size (including polyps and deep choroidal vessels) from baseline over time up to month 12. Qualitative grading of the angiograms and photographs, as well as polyps and branched choroidal vascular networks, was done by a single physician at months 3, 6, 9, and 12 and compared with baseline as unchanged, resolved, improved, worsened, or cannot determine.

Statistical analysis

Safety was evaluated by a descriptive analysis of all non-serious and serious AEs, angiographic assessments, physical examinations, vital signs, ocular examinations, and visual acuity measurements. Missing values of BCVA and OCT measurements were imputed using the last observation carried forward method.

Results

Patient population

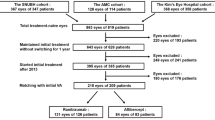

Twenty patients were enrolled in the study (n=15 for high dose; n=5 for standard dose). Two of 20 patients (10%) were lost to follow-up by month 12 (one patient each from the high-dose and standard-dose group). Patients in the high-dose group received an average of 8.4 doses compared with 6 doses for the standard-dose group.

Table 1 includes baseline characteristics of the high- and standard-dose groups. The majority of patients were Black or White (one patient was Asian), aged between 35 and 76 years, with an average body mass index of 33.4 kg/m2. On average, at baseline, the standard-dose group had better vision and worse OCT, and the high-dose group had thinner CFT, a greater proportion of previously treated patients, and more patients with fibrosis. Owing to these differences, comparisons were not made between the two groups; the text focuses on the results in the high-dose group.

The high-dose group had an average body mass index of 35.3 kg/m2 and included five (33%) patients with sleep apnea. Of the five individuals with known, patient-reported sleep apnea, four were Black, and all five patients were obese.

Adverse events

All ocular AEs and notable AEs are listed in Table 2. The majority of ocular or systemic AEs were mild or moderate. The severe ocular AE was increased cataract in one patient; no retinal detachments, retinal tears, or endophthalmitis were reported. No patients experienced ≥30 ETDRS letter loss in BCVA in this study. The most common ocular AEs overall were blurred or decreased vision (loss ranging from 6–16 letters; n=6; occurred twice in one patient), floaters (n=6), and dark spots (n=3). Two patients in the high-dose group experienced subretinal hemorrhage consistent with PCV activity (one of these patients had two separate episodes); all events were moderate in severity. One patient in the standard-dose group had mildly elevated blood pressure at month 6. No severe systemic AEs were deemed study treatment-related by the investigator, and no deaths or acute arterial thromboembolic events occurred. No patients in either group received or required rescue PDT or other non-anti-VEGF therapies.

Visual acuity end points

At month 12, the mean overall change in BCVA from baseline was +6.7 ETDRS letters in patients treated with ranibizumab 1.0 or 2.0 mg (Figure 1a). For patients who only had gains, the mean change in BCVA from baseline at month 12 was +9.7 ETDRS letters. The median change in BCVA was +5.0, +7.0, +6.0, and +5.0 letters at months 3, 6, 9, and 12, respectively.

Mean change from baseline over time up to month 12: (a) BCVA (ETDRS letters) in all eyes. (b) CFT in all eyes. (c) BCVA (ETDRS letters) in eyes with baseline CFT >300 μm. (d) CFT in eyes with baseline CFT >300 μm. *At month 9, n=13 for high dose and n=4 for standard dose. Error bars represent ±1 SEM. BCVA, best-corrected visual activity; CFT, central foveal thickness; ETDRS, Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study.

The proportion of patients treated with ranibizumab 1.0 or 2.0 mg who gained 5, 10 and 15 or more letters over time was generally consistent over the course of the study (Supplementary Figure 1).

Anatomic end points

At month 12, the mean overall change from baseline in CFT as assessed by OCT was −49.7 μm for the high-dose group (Figure 1b). Mean change in macular volume from baseline over time up to month 12 was −0.89 mm3. Seven (47%) of 15 patients had no evidence of subretinal OCT edema at month 12.

Mean changes in choroidal thickness as assessed by OCT were minor at the fovea, temporal, nasal, inferior, and superior locations (Supplementary Table 1). At month 3, the high-dose group showed a decrease in thickness on average in the fovea and inferior location; 46–73% of patients had decreased thickness in the various locations and 73% of patients experienced decreased inferior thickness. At month 12, there were minor decreases on average at all locations.

The mean changes from baseline in the total area of FA CNV leakage and in ICG CNV lesion size over 12 months are depicted in Figure 2. A qualitative grading of fundus photographs, overall ICG, and lesion size on FA showed that the majority of eyes were stable or unchanged (Supplementary Figure 2). On ICG, similar results were seen for polyp size and branching choroidal vascular networks. At month 12, of 15 eyes treated with high-dose ranibizumab, polyps were resolved in 2 eyes (13%), stable in 9 eyes (60%), and worsened in 3 eyes (20%); 1 eye was uninterpretable.

Cases are presented in Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure 3. Individual patient results are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

Fundus photographs and ICG angiograms from a 56-year-old White male, treatment-naïve randomized to high-dose ranibizumab (1.0 or 2.0 mg). Fundus photographs demonstrate marked resolution of blood, lipid, and retinal thickening with contraction of peripapillary-based PCV complex at 12 months from baseline. ICG angiograms demonstrate polyp regression without resolution at 12 months. Baseline visual acuity was 77 ETDRS letters (Snellen equivalent ~20/32), which improved 7 letters to 84 letters (Snellen equivalent ~20/20) at 12 months. Baseline OCT central subfield thickness was 350 μm and thinned to 226 μm at 12 months. ETDRS, Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study; ICG, indocyanine green; OCT, optical coherence tomography; PCV, polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy.

End points in patient subgroups

Visual acuity and anatomic end points for patient subgroups based on baseline characteristics, including CFT >300 μm, subfoveal disease, fibrosis, and treatment history, are reported in Supplementary Table 3. In high-dose ranibizumab-treated patients with baseline CFT >300 μm (4/15 (27%)), mean overall change in BCVA from baseline at month 12 was +12.5 ETDRS letters (Figure 1c), and mean change in CFT from baseline at month 12 was −164.5 μm (Figure 1d).

Discussion

Standard- and high-dose ranibizumab monotherapy was generally well tolerated. Visually significant ocular or systemic AEs were predominantly mild or moderate. No significant safety signals were observed in either group. Patients with PCV demonstrated positive visual acuity and anatomic response to treatment with high-dose ranibizumab (1.0 or 2.0 mg). At month 12, the mean overall change from baseline in BCVA was +6.7 letters and in CFT was −49.7 μm.

Due to the baseline differences between the standard- and high-dose groups, no comparisons were made between the two groups. The standard-dose group on average had better vision and worse OCT at baseline. The high-dose group had thinner CFT on average at baseline, a greater proportion of previously treated patients, and more patients with fibrosis at baseline, suggesting their disease was more chronic and may be less responsive anatomically. However, eyes in the high-dose group with fibrosis demonstrated visual gains, despite being potentially limited by chronicity and fibrosis. On average, patients in the high-dose group received more doses in the study (8.4 vs 6 doses in the standard-dose group), which may also indicate a more chronic recalcitrant patient base. Finally, a greater proportion of eyes treated with high-dose ranibizumab had peripapillary-located lesions at baseline, which may have contributed to improved acuity outcomes.

In patients with baseline CFT >300 μm, considerable BCVA and CFT improvement was seen in the high-dose group. This finding may indicate a more favorable anatomic result with high-dose ranibizumab for eyes with more active exudation at baseline. The 15-letter gain observed for treatment-naive high-dose eyes (n=4) further supports the need for continued investigation of high-dose ranibizumab monotherapy for non-Asian PCV.

A study limitation is the inability to make comparisons between the high- and standard-dose groups. The standard-dose control group was required by the United States Food and Drug Administration. The angiographic assessments were quite variable and were also subject to intra-observer variability.

Our previous study7 showed good results with ranibizumab 0.5 mg and overall supports anti-VEGF monotherapy as a viable therapy for non-Asian PCV. The majority of patients with baseline CFT >300 μm had favorable vision gains and CFT reduction. Because most studies on PCV have been conducted in Asian patients, this study provides needed information on PCV in non-Asian patients. Similar to previous studies in Asian patients with PCV,15, 24 resolution of polyps and branching choroidal vascular networks on ICG was not seen. Sleep apnea may be a potential risk factor in non-Asian PCV, particularly in Black patients with high body mass index. Physiologic manifestations of sleep apnea, including nocturnal hypertension and hypotension, hypoxia, carbon dioxide retention, Valsalva maneuvers, and increased intracranial pressure, may have a role in choroidal vascular abnormalities observed.30, 31, 32 Other studies have found unimpaired choroidal vascular reactivity in otherwise healthy men with obstructive sleep apnea.33, 34 Because other systemic comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension exist in this population, further investigation of sleep apnea in PCV is required. Our data support querying PCV patients regarding a history of sleep-disordered breathing; those with positive symptoms or a history of sleep apnea should be referred for diagnostic sleep testing or sleep apnea management.

In conclusion, high-dose ranibizumab (1.0 or 2.0 mg) monotherapy may be an option for the treatment of non-Asian patients with PCV. Further investigation is needed with both standard-dose and high-dose ranibizumab monotherapy for the treatment of non-Asian PCV.

References

Koh AH, Chen LJ, Chen SJ, Chen Y, Giridhar A, Iida T et al. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: evidence-based guidelines for clinical diagnosis and treatment. Retina 2013; 33: 686–716.

Matsuoka M, Ogata N, Otsuji T, Nishimura T, Takahashi K, Matsumura M . Expression of pigment epithelium derived factor and vascular endothelial growth factor in choroidal neovascular membranes and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 2004; 88: 809–815.

Tong JP, Chan WM, Liu DT, Lai TY, Choy KW, Pang CP et al. Aqueous humor levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and pigment epithelium-derived factor in polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy and choroidal neovascularization. Am J Ophthalmol 2006; 141: 456–462.

Saito M, Iida T, Kano M, Itagaki K . Two-year results of intravitreal ranibizumab for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy with recurrent or residual exudation. Eye (Lond) 2013; 27: 931–939.

Hikichi T, Higuchi M, Matsushita T, Kosaka S, Matsushita R, Takami K et al. One-year results of three monthly ranibizumab injections and as-needed reinjections for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in Japanese patients. Am J Ophthalmol 2012; 154: 117–124.

Hikichi T, Higuchi M, Matsushita T, Kosaka S, Matsushita R, Takami K et al. Results of 2 years of treatment with as-needed ranibizumab reinjection for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 2013; 97: 617–621.

Marcus DM, Singh H, Lott MN, Singh J, Marcus MD . Intravitreal ranibizumab for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in non-Asian patients. Retina 2013; 33: 35–47.

Yonekawa Y . Aflibercept for the treatment of refractory polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Can J Ophthalmol 2013; 48: e59–e60.

Cho HJ, Kim JW, Lee DW, Cho SW, Kim CG . Intravitreal bevacizumab and ranibizumab injections for patients with polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Eye (Lond) 2012; 26: 426–433.

Cheng CK, Peng CH, Chang CK, Hu CC, Chen LJ . One-year outcomes of intravitreal bevacizumab (avastin) therapy for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Retina 2011; 31: 846–856.

Saito M, Iida T, Kano M . Intravitreal ranibizumab for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy with recurrent or residual exudation. Retina 2011; 31: 1589–1597.

Kokame GT . Prospective evaluation of subretinal vessel location in polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV) and response of hemorrhagic and exudative PCV to high-dose antiangiogenic therapy (an American Ophthalmological Society thesis). Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 2014; 112: 74–93.

Kokame GT, Yeung L, Lai JC . Continuous anti-VEGF treatment with ranibizumab for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: 6-month results. Br J Ophthalmol 2010; 94: 297–301.

Kokame GT, Yeung L, Teramoto K, Lai JC, Wee R . Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy exudation and hemorrhage: results of monthly ranibizumab therapy at one year. Ophthalmologica 2014; 231: 94–102.

Koh A, Lee WK, Chen LJ, Chen SJ, Hashad Y, Kim H et al. EVEREST study: efficacy and safety of verteporfin photodynamic therapy in combination with ranibizumab or alone versus ranibizumab monotherapy in patients with symptomatic macular polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Retina 2012; 32: 1453–1464.

Jeon S, Lee WK, Kim KS . Adjusted retreatment of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy after combination therapy: results at 3 years. Retina 2013; 33: 1193–1200.

Nemoto R, Miura M, Iwasaki T, Goto H . Two-year follow-up of ranibizumab combined with photodynamic therapy for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Clin Ophthalmol 2012; 6: 1633–1638.

Saito M, Iida T, Kano M, Itagaki K . Two-year results of combined intravitreal ranibizumab and photodynamic therapy for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2013; 251: 2099–2110.

Oishi A, Kojima H, Mandai M, Honda S, Matsuoka T, Oh H et al. Comparison of the effect of ranibizumab and verteporfin for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: 12-month LAPTOP study results. Am J Ophthalmol 2013; 156: 644–651.

Hatz K, Prunte C . Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in Caucasian patients with presumed neovascular age-related macular degeneration and poor ranibizumab response. Br J Ophthalmol 2014; 98: 188–194.

Sho K, Takahashi K, Yamada H, Wada M, Nagai Y, Otsuji T et al. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: incidence, demographic features, and clinical characteristics. Arch Ophthalmol 2003; 121: 1392–1396.

Ciardella AP, Donsoff IM, Huang SJ, Costa DL, Yannuzzi LA . Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Surv Ophthalmol 2004; 49: 25–37.

Yannuzzi LA, Wong DW, Sforzolini BS, Goldbaum M, Tang KC, Spaide RF et al. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy and neovascularized age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 1999; 117: 1503–1510.

Lai TY, Lee GK, Luk FO, Lam DS . Intravitreal ranibizumab with or without photodynamic therapy for the treatment of symptomatic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Retina 2011; 31: 1581–1588.

Matsumiya W, Honda S, Kusuhara S, Tsukahara Y, Negi A . Effectiveness of intravitreal ranibizumab in exudative age-related macular degeneration (AMD): comparison between typical neovascular AMD and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy over a 1 year follow-up. BMC Ophthalmol 2013; 13: 10.

Matsumiya W, Honda S, Bessho H, Kusuhara S, Tsukahara Y, Negi A . Early responses to intravitreal ranibizumab in typical neovascular age-related macular degeneration and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. J Ophthalmol 2011; 2011: 742020.

Busbee BG, Ho AC, Brown DM, Heier JS, Suner IJ, Li Z et al. Twelve-month efficacy and safety of 0.5 mg or 2.0 mg ranibizumab in patients with subfoveal neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2013; 120: 1046–1056.

Ho AC, Busbee BG, Regillo CD, Wieland MR, Van Everen SA, Li Z et al. Twenty-four-month efficacy and safety of 0.5 mg or 2.0 mg ranibizumab in patients with subfoveal neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2014; 121: 2181–2192.

Birnbaum AD, Fawzi AA, Rademaker A, Goldstein DA . Correlation between clinical signs and optical coherence tomography with enhanced depth imaging findings in patients with birdshot chorioretinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol 2014; 132: 929–935.

Geiser MH, Riva CE, Dorner GT, Diermann U, Luksch A, Schmetterer L . Response of choroidal blood flow in the foveal region to hyperoxia and hyperoxia-hypercapnia. Curr Eye Res 2000; 21: 669–676.

Kergoat H, Faucher C . Effects of oxygen and carbogen breathing on choroidal hemodynamics in humans. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1999; 40: 2906–2911.

Abraham A, Peled N, Khlebtovsky A, Benninger F, Steiner I, Stiebel-Kalish H et al. Nocturnal carbon dioxide monitoring in patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2013; 115: 1379–1381.

Tonini M, Khayi H, Pepin JL, Renard E, Baguet JP, Levy P et al. Choroidal blood-flow responses to hyperoxia and hypercapnia in men with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 2010; 33: 811–818.

Khayi H, Pepin JL, Geiser MH, Tonini M, Tamisier R, Renard E et al. Choroidal blood flow regulation after posture change or isometric exercise in men with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011; 52: 9489–9496.

Acknowledgements

Courtney Roberts, Allison Foster, Jared Gardner, and Siobhan Ortiz provided technical and data support. Support for third-party writing assistance for this manuscript was provided by Grace H. Lee at Envision Scientific Solutions and funded by Genentech, Inc. This study was funded as an investigator-initiated trial by Genentech, Inc., South San Francisco, CA, and conducted at Southeast Retina Center, Augusta, GA. The authors have no proprietary interest. Genentech, Inc., participated in the review of the manuscript. Genentech, Inc., did not participate in the study design; conducting the study; data collection, management, analysis, and interpretation; or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

DMM is a consultant for Genentech, Inc., Regeneron, and Thrombogenics. DMM and HS have received clinical research support from Acucela, Alcon, Allergan, Genentech, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Ophthotech, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Thrombogenics. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Eye website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marcus, D., Singh, H., Fechter, C. et al. High-dose ranibizumab monotherapy for neovascular polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in a predominantly non-Asian population. Eye 29, 1427–1437 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2015.150

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2015.150

This article is cited by

-

Combined Use of Anti-VEGF Drugs Before and During Pars Plana Vitrectomy for Severe Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy

Ophthalmology and Therapy (2023)