Abstract

Purpose

Primary intraosseous haemangioma (IOH) is a rare benign neoplasm presenting in the fourth and fifth decades of life. The spine and skull are the most commonly involved, orbital involvement is extremely rare. We describe six patients with cranio-orbital IOH, the largest case series to date.

Patients and methods

Retrospective review of six patients with histologically confirmed primary IOH involving the orbit. Clinical characteristics, imaging features, approach to management, and histopathological findings are described.

Results

Five patients were male with a median age of 56. Pain and diplopia were the most common presenting features. A characteristic ‘honeycomb’ pattern on CT imaging was demonstrated in three of the cases. Complete surgical excision was performed in all cases with presurgical embolisation carried out in one case. In all the cases, histological studies identified cavernous vascular spaces within the bony tissue. These channels were lined by single layer of cytologically normal endothelial cells.

Discussion

IOCH of the cranio-orbital region is rare; in the absence of typical imaging features, the differential diagnosis includes chondroma, chondrosarcoma, bony metastasis, and lymphoma. Surgical excision may be necessary to exclude more sinister pathology. Intraoperative haemorrhage can be severe and may be reduced by preoperative embolisation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intraosseous haemangiomas (IOH) are rare benign neoplasms, with the spine and skull most commonly involved.1 Involvement of the facial skeleton, in particular the orbit, is extremely rare. We present six patients with periorbital IOH and describe the clinical presentation, imaging, surgical management, and histopathological features of this unusual intraosseous lesion.

Case reports

Patient 1

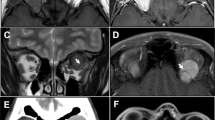

A fit, 61-year-old man gave a 6-year history of a gradually enlarging mass, centred on the right inferior orbital rim (Figure 1a). A bony hard swelling was palpable, associated with limited infraduction and diplopia on downgaze. A contrast-enhanced CT showed a well-defined, avidly-enhancing mass arising from the infraorbital groove, without orbital invasion or destruction of adjacent tissues; small signal voids within the mass, suggested a vascular lesion (Figure 1b).

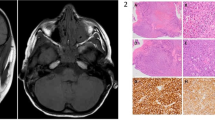

Patient 1: (a) bony mass over the right inferior orbital rim; (b) contrast-enhanced CT identifying a mass arising in the region of the frontomaxillary suture; (c and d) complete excision via a swinging lid flap; and (e and f) histological sections show characteristic vascular spaces between bony trabeculae with high power illustrating vascular channels lined by a flat layer of cytologically bland endothelial cells surrounded by loose fibrous tissue. Patient 2: (g) CT showing typical ‘sunburst’ radiological changes in IOH arising within the frontal bone; (h) extension of the lesion into the frontal sinus; (i) CT 3D reconstruction illustrating reticular bony configuration; (j) Complete excision via a frontal craniectomy; and (k) excision specimen.

Complete excision was performed via a swinging lower eyelid flap (Figures 1c and d). Histological examination revealed chips of cancellous bone containing cavernous vascular spaces and thin-walled blood vessels, the latter lined by a single layer of normal endothelium. The vessels permeated the bone marrow and pre-existing trabeculae, with no evidence of malignancy (Figures 1e and f).

Patient 2

After 2 years of a slowly enlarging midline frontal swelling, a 49-year-old man presented with 6 months of headache and rapid expansion of his forehead lesion. Urgent imaging identified an intradiploeic mass within the frontal bone, bulging into the anterior cranial fossa and frontal sinus, with a thin shell of residual cortex (Figures 1g–i). The lesion was excised with frontal craniectomy and the defect was repaired with a titanium cranioplasty (Figures 1j and k). Histological sections confirmed a cavernous IOH.

Patient 3

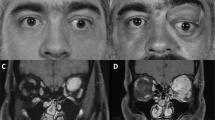

A 59-year-old man presented with a 6-month history of a hard lump over his left orbito-temporal region (Figure 2a), causing a mechanical ptosis with restricted upgaze and diplopia. MRI revealed an enhancing mass, arising from the zygomatic process and frontal bone tuberosity. (Figure 2b). The lesion extended into the frontal sinus and temporalis fossa (Figure 2c) and was noted to receive blood supply from distal branches of the middle meningeal artery. Expansion into the neighbouring extraconal space was also seen, displacing the extraocular muscles inferomedially (Figure 2d).

Patient 3: (a) left superolateral mass causing ptosis and restricted eye movements; (b) MRI identifying enhancing mass within the left orbit; (c) extension of the lesion into the frontal sinus and temporal fossa; and (d) mass effect within the lateral bony orbit. Patient 4: (e) axial CT showing an intradiploeic mass in the inferolateral orbit, with a typical ‘sunburst’ appearance.

Transfemoral embolisation was performed before complete excision of the mass through a frontal craniectomy with minimal intraoperative haemorrhage. The diagnosis was confirmed histologically.

The remaining cases are summarised in Table 1.

Discussion

Haemangiomas and vascular malformations of the orbital soft tissues are not uncommon, but benign vascular tumours of the orbital bones are extremely rare.1 IOH is a hamartoma that typically affects the axial skeleton and contains anomalous proliferations of endothelial-lined channels within normal bone. They represent less than 1% of all bone tumours, and although most frequently encountered in women in the fourth or fifth decade of life (3:1 female predominance), they have also been encountered in the newborn and very elderly patients.2, 3, 4, 5

The pathogenesis of IOH remains uncertain, although there was no history of trauma in our patients, the tumour may arise from local expression of vascular growth factors in response to subclinical inflammatory changes after injury.6

Based upon vessel calibre, two subtypes of IOH have been described: Cavernous haemangioma is the commonest, containing collections of large, thin-walled vessels lined by a single layer of endothelial cells. Although they are indistinguishable from cavernous IOHs on clinical and radiographic grounds, capillary IOHs are composed of finer and more tortuous vessels, separated by normal bone tissue.7, 8

Involvement of the facial skeleton is uncommon,5, 8 with primary orbital IOH being exceptionally rare.2, 3, 4, 5, 7 Literature reviews have identified that most lesions are superiorly located with a third affecting the frontal and zygomatic bones, respectively.7, 9 Medial and inferior lesions were less commonly encountered. This is in contrast to the current series, in which half of the lesions involved the maxilla, suggesting that there may be a predilection for this site.

The typical clinical presentation is of a gradually enlarging, non-tender bony mass, although rapid enlargement—as seen in patient 2—can be associated with pain. Bluish discolouration, bruit, and spontaneous haemorrhage occurs rarely but would suggest a vascular lesion.10 Depending on the size and location, IOHs may cause ptosis, eyelid retraction, proptosis, restricted eye movements, or visual impairment. Differential diagnosis includes aneurysmal bone cysts, fibrous dysplasia, rhabdomyosarcomas, eosinophilic granulomas, and malignant tumours (such as osteo or chondrosarcomas, multiple myeloma, or metastases).4, 7 Patient 6 presented with epiphora due to an inferomedial lesion compressing the nasolacrimal duct. It is imperative that these lesions are identified before proceeding with dacryocystorhinostomy, as they can be associated with considerable intraoperative bleeding.9

Although often radiolucent on plain X-radiographs, CT findings typically show a characteristic ‘honeycomb’ or ‘sunburst’ pattern, with fine radiating reticulated lines or trabeculae, as observed in patient 2.2, 6

IOHs typically follow a benign course and can be observed in the absence of troublesome symptoms, with surgery reserved for patients with mass effect, haemorrhage, or significant aesthetic concerns.7 Although en bloc excision has been advocated, partial resection can achieve good cosmetic results with no evidence of recurrence. Preoperative imaging is desirable, as an unplanned biopsy may lead to severe haemorrhage8, and preoperative embolisation can usefully reduce this risk of haemorrhage.

References

Hornblass A, Zaidman GW . Intraosseous orbital cavernous haemangioma. Ophthalmology 1981; 88: 1351–1355.

Colombo F, Cursiefen C, Hofmann-Rummelt C, Holbach LM . Primary intraosseous cavernous haemangioma of the orbit. Am J Ophthalmol 2001; 131: 151–152.

Relf SJ, Bartley GB, Unni KK . Primary orbital intraosseous haemangioma. Ophthalmology 1991; 98: 541–546.

Savastano G, Russo A, Dell’Aquila A . Osseous haemangioma of the zygoma: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997; 55: 1352–1356.

Tang Chen Y-B, Wornom IL, Whitaker LA . Intraosseous malformations of the orbit. Plast Reconstr Surg 1991; 87: 946–949.

Sweet C, Silbergleit R, Mehta B . Primary intraosseous haemangioma of the orbit: CT and MR appearance. Am J Neuroradiol 1997; 18: 379–381.

Rios Dias GD, Velasco Cruz AA . Intraosseous haemangioma of the lateral orbital wall. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2004; 20: 27–29.

Cheng N-C, Lai D-M, Hsie M-H, Liao S-L, Tang Chen Y-B . Intraosseous haemangioma of the facial bone. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006; 117: 2366–2372.

Madge SN, Simon S, Abidin Z, Ghabrial R, Davis G, McNab A et al. Primary orbital intraosseous haemangioma. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2009; 25: 37–41.

Sary A, Yavuzer R, Latfoglu O, Celebi MC . Intraosseous zygomatic haemangioma. Ann Plast Surg 2001; 46: 659–662.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gupta, T., Rose, G., Manisali, M. et al. Cranio-orbital primary intraosseous haemangioma. Eye 27, 1320–1323 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2013.162

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2013.162