Abstract

Purpose

This study assessed the role of specialist optometrists who were working in the community and sharing the care for glaucoma patients with, and under close supervision of, a consultant ophthalmologist working in the Hospital Eye Services (HES) to ensure high-quality standards, safety, and care.

Methods

From February 2005 onwards, the majority of all new glaucoma referrals to our eye department were diverted to our specialist optometrists in glaucoma (SOGs) in their own community practices. Selected patients in the HES setting who were already diagnosed with stable glaucoma were also transferred to the SOGs. The completed clinical finding details of the SOGs, including fundus photographs and Humphrey visual field tests, were scrutinised by the project lead.

Results

This study included 1184 new patients seen by specialist optometrists between February 2005 and March 2007. A total of 32% of patients were referred on to the hospital, leaving the remaining 68% patients to be seen for at least their next consultation in the community by the SOGs. The following levels of disagreement were observed between SOGs and the project lead: on cup:disc ratio (11%), visual field interpretation (7%), diagnosis (12%), treatment plan (10%), and outcome (follow-up interval and location) (17%).

Conclusion

This study indicates that there is potential for a significant increase in the role of primary care optometry in glaucoma management. The study also confirms a need for a significant element of supervision and advice from a glaucoma specialist. The important issue of cost effectiveness is yet to be confirmed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glaucoma is a common blinding disorder requiring life-long care. The prevalence of primary open angle glaucoma varies depending upon the age and race of the patients.1 Approximately 15–20% of new referrals to the Hospital Eye Service (HES) either have or are suspected of having glaucoma,2, 3, 4, 5 and a quarter of those attending the outpatient clinic are glaucoma follow-up patients.6 The projected demand for HES is estimated to rise by 35% by the year 2020,7, 8 and will include a significant number of glaucoma patients, glaucoma suspects, and those at risk. Because the HES is experiencing this marked increase in workload, innovative ways of dealing with this emerging crisis are being examined. A significant proportion of new glaucoma referrals are unnecessary and create an excess demand on the already overstretched eye departments. Engaging specialist optometrists in glaucoma (SOGs) for referral refinement may result in a significant reduction in wasted hospital visits.

We therefore proposed a pathway using the established skills of trained and accredited optometrists to perform initial assessment of such patients, and co-manage patients with stable glaucoma and/or glaucoma suspects. In late 2002, the Department of Health (DOH) established the National Eye Care Steering Group to develop care pathways for cataract, glaucoma, and low-vision and age-related macular degeneration, and funding was provided for pilot sites. As one of these sites for a glaucoma pathway using optometrists with a special interest, we report our experience in the Peterborough catchment area.

The aims for the project were as follows:

-

To reduce the number of hospital visits by glaucoma and glaucoma-related patients, including false positives;

-

To reduce waiting times to initial assessment for all new glaucoma suspects; and

-

To expedite follow-up and treatment for stable glaucoma or at-risk patients by diverting these patients to a community setting and offering a choice of SOG practices.

Of paramount importance to the HES in effecting this significant change in practice was the maintenance of high-quality care and safety for the patients through training, supervision, and audit of the SOG involvement by the HES.

Materials and methods

Selection of optometrists and training scheme for accreditation

In all, 20 optometrists were invited to participate in the project through a series of lectures on various practical aspects of glaucoma. Of these, 10 optometrists accepted to undergo further training. Training involved 9 h of theory lectures and three practical sessions (each session lasts for 3 h); thus, on average 18 h altogether. Theory sessions covered basic aspects of glaucoma, including diagnosis and management of different types of glaucoma. Practical sessions mainly focussed on accuracy of intraocular pressure measurement using Goldmann applanation tonometry (GAT) (Goldmann Tonometer AT 900, Haag-Streit International, Koeniz, Switzerland), as well as anterior chamber angle assessment by Van Herick's technique (www.gonioscopy.org/vanHerick.html). Van Herick's technique uses an assessment of the peripheral anterior chamber depth as a surrogate for angle width. Slit lamp (BM 900, Haag-Steit International) assessment of the optic disc through a 90-dioptre Volk lens (Volk Optical, Mentor, OH, USA) and interpretation of Humphrey visual fields (Carl Zeiss Ophthalmic Systems, Humphrey Division, CA, USA) were also covered. Training concentrated on the recognition of relevant co-pathology and the eliciting of important signs that led to accurate glaucoma classification and diagnosis. Those optometrists who reached consistently high levels of concordance with the ophthalmologist assessors were invited to participate in the shared care programme. The invited optometrists once accredited became Specialist optometrist in glaucoma (SOG), accepting the commission on the behalf of Peterborough and Stamford NHS Trust to examine patients in their respective community practices. All glaucoma assessments carried out by the optometrists had a second virtual evaluation in HES, in which decisions on diagnosis and management were made by the project lead.

Equipment used in the optometrists’ practices

Five optometrists’ practices were issued with the necessary standardised examination equipment facilitating comprehensive glaucoma assessments, including a Haag-Streit slit lamp, Goldmann applanation tonometer, Humphrey visual field analyser, and digital camera (Topcon TRC NW6S camera, Topcon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The costs of equipments were met from the fund provided by the DOH. The SOGs used a standard form to record clinical data. After collating clinical data and investigations, they were despatched to the project lead for evaluation.

Referral criteria and standard protocol

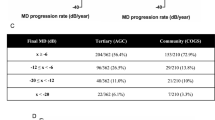

From February 2005 to March 2007, the majority (1184 out of 1531 patients, 77.3%) of new glaucoma patients, stable follow-up glaucoma patients, and patients at risk of glaucoma, including those with ocular hypertension (OHT) (Table 1), were assessed by SOGs in the community. Inappropriate patients were referred to the HES and removed from the scheme; for example, patients with very poor vision, media opacity, advanced glaucoma, and uncontrolled or unilateral glaucomas (Table 2).

Consultant ophthalmologists and project administrators involved at the inception reached agreement with the relevant local Primary Care Trust (Peterborough) represented by general manager and general practitioners (GPs). Exhaustive collaborative discussions among all consultant ophthalmologists in the hospital department resulted in the process definition, design of audit, follow-up, and treatment protocols.

A standard glaucoma screening assessment and referral form was used to record data at the initial and follow-up visits by the SOG (Figure 1) and included a complete medical, ophthalmic, and family history. A systematic ophthalmic examination was carried out as described in the form. The ocular examination included

-

Intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement using a Goldmann applanation tonometer,

-

Irido-corneal angle depth assessment by Van Herick's technique,

-

and visual fields with a Humphrey field analyser.

The ‘SITA FAST’ 24-2 pattern visual field was recorded on all patients at each visit. All patients were subjected to pupillary dilatation, except those with shallow peripheral anterior chambers (ie, grade <2). These patients were referred directly into the HES laser clinic for confirmation of shallow peripheral anterior chamber and, where indicated, underwent further management, but their data is not included in this paper. Optic disc vertical cup/disc ratios were measured and recorded by the SOG using biomicroscopy and a 90-dioptre lens and, on the basis of an agreed set of criteria, graded as normal, suspicious, or abnormal. Their assessment was directly compared with the assessment made by the project lead who was scrutinising the digital photograph of the optic nerve head. Similarly, SOGs expressed their opinion of the visual field performances, including the reliability of the witness, by grading visual field as normal, suspicious, or abnormal. Finally, the SOG was encouraged to offer a working diagnosis, and suggest follow-up and treatment category using the standard form. The conclusions of the SOGs were then compared with the project lead's overall opinion. Collaborators in the ophthalmic unit prepared a guidance document (Table 3) to assist in decision making by the SOG, which was continuously reviewed and updated in the department. These follow-up guidelines are in line with the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines, April 2009.27 All queries or comments by the SOGs were conveyed to the HES, using the assessment form and vice versa from HES to the SOG. Advanced or worrying cases were referred to the HES for immediate attention.

To reduce variability, all data collected by the SOGs were assessed by the same lead consultant. A separate standard glaucoma assessment and referral audit form was completed to assist in determining the level of agreement between the consultant and the SOGs. By analysis of the anonymous data of the SOGs, the project lead formed a diagnosis and treatment plan. A direct comparison was then made with the SOG conclusions and the level of agreement was classified as ‘in agreement’ (IA), ‘no significant disagreement’ (NSD), and ‘significant disagreement’ (SD). So far, we have not carried out any verification of intra-expert variation of the lead consultant.

A standard letter was sent to each patient, the GP, the SOG, and the community optometrist. A copy of the audit form was sent to the individual SOG concerned to provide feedback and enhance glaucoma education and experience. Treatment was commenced for those patients who fulfilled the necessary criteria and was initiated by their GP through written recommendation. All these patients were reviewed at 3 months by the SOG to measure IOP and assess the response to treatment, which was adjusted as necessary on the advice of the project lead. If required, the medications were adjusted by the project lead and again new medications were prescribed by the GP. Visual field tests were repeated in all treated patients at this same interval. All patients who were newly diagnosed with glaucoma were reviewed at the hospital eye service at 3 months or later. Patients with poor IOP control, that is, IOP above target pressure, evidence of glaucoma progression, poor vision, and so on, were also referred back to the HES (Table 2). After each SOG episode and subsequent consultant overview, the patient was informed about their condition and progress, using the standard letter sent from the HES. The SOG and GP were also informed by the standard letter. Audited findings at regular intervals indicated a convergence of agreement and compliance with protocols and guidelines over time.

A uniform customised questionnaire was used to assess patients’ satisfaction. The data retrieved were evaluated to analyse the source of referrals into the SOG scheme, and the level of agreement between SOG and consultant on findings, treatment, outcome (follow-up interval and location), and patient satisfaction.

Results

A total of 1184 new patients were assessed between February 2005 and March 2007. Of the five practices involved, four were independent optometrists and one a well-known high street franchise (Specsavers, Peterborough, UK). On an average, it took 40 min for the optometrist to assess each patient. The average waiting time from referral to SOG assessment was 36 days (median 36, interquartile range 0–63). The waiting time offered in each practice was 2–4 weeks. The average waiting time between SOG assessment and HES evaluation was 15 days (SD 10). One practice saw 46% of the total number of patients, and the two most involved practices saw 67% of patients. Figure 2 shows the number of patients seen by each SOG. Of those referring into the scheme, GPs and community optometrists (COs) accounted for approximately 38% of all referrers (Figure 3). Out of a total of 2368 digital fundal images sent to HES, 360 (15.2%) were unusable due to cataract. Data relating to unreliable visual fields were not collected. Unusable visual fields were very small (0.5%).

Glaucoma risk factors were present in 26% of cases and these risk factors are shown in Figure 1. These data were not retrieved for analysis, but will feature in a future publication. The diagnoses established include glaucoma suspect (19%), ocular hypertension (17%), primary open angle glaucoma (9%), and so on (Figure 4). Of the initial 10 SOGs, four withdrew, and at the time of submitting this article six SOGs remained. Of these four SOGs, one retired, two moved from the area, and the fourth withdrew because of personal reasons. Their inputs were also included in this study. A significant disagreement between the project lead's appraisal and findings of the SOGs was observed in the following (see Figure 5): optic nerve morphology (11%), visual field (7%), diagnosis (12%), treatment (10%), and follow-up (17%).

A total of 68% of patients were followed up in the community (Figure 3) and of these, 22% were seen at 12 months and 21% at 6 months. In all, 32% of patients were referred back to HES because of various reasons outlined in Table 2. The patient satisfaction survey involved 100 consecutive patients out of initial 389 patients with 72 patients returning data. Thus, 96% of returned questionnaires indicated satisfaction with the scheme (Table 4). One case experienced delay of >6 months in receiving information from the SOG and required clinical incident reporting. Nine patients expressed some confusion about the details of their follow-up appointment.

Some of the SOGs practices already had a slit lamp and digital camera before enrolling into the scheme, which in turn reduced the total cost of equipping them. The cost of individual instruments were: Haag-Streit slit lamp, £10 890 ($17 859); Goldmann applanation tonometer, £1023 ($1657.62); Humphrey visual field analyser, £15 628 ($25 317.36); and Topcon digital camera, £25 000 ($40 500) The fiscal issues relating to this scheme are under continued review and will be addressed in future publications.

Discussion

Glaucoma is the second leading cause of blindness in the world,8 and it is believed that optimum treatment in the early stages may preserve useful vision.9 Glaucoma patients account for approximately 25% of return visits to hospital eye departments,6 and is, in part, responsible for increased demands on HES. To reduce the burden on ophthalmic departments and develop more patient-centred services in their communities, various care pathways have been developed in different parts of the United Kingdom.6, 9, 10, 11, 12 Innovative pathways include refining glaucoma referrals to HES or alternative pathways by optometrists.11, 13, 14 In-house trained optometrists,12 orthoptists, and nurses25 are used in some parts of the United Kingdom, with a perceived advantage being linked to close supervision. We believe that our study suggests that highly motivated and skilled community-based specialist optometrists are safe and reliable local resources in providing a convenient, appropriate, and quality-assured service for the shared care of glaucoma patients.

The Bristol shared care glaucoma study also used trained community optometrists, but the strict inclusion and exclusion criteria reduced the proportion of patients included in the scheme.6, 10 A study carried out by Bane et al18 showed that agreement between consultant and optometrist was as good as between associate specialist career grade ophthalmologist and consultant. Azuara-Blanco et al19 have also shown that using community optometrists for shared care was feasible, with no marked or statistically significant differences between patients being seen by ophthalmologists in training in a hospital clinic and trained and accredited glaucoma specialists optometrists.

The Humphrey ‘SITA FAST’ 24-2 thresholding algorithm was used uniformly, and reduced testing time with this programme facilitated increased patient throughput.26 The SITA FAST programme can improve reliability,15, 26 has recently been reported to be used by 42% of the consultants around the United Kingdom,20 and has been the programme of choice in the Peterborough Eye Department.

The UK NICE guidelines, April 2009,27 list gonioscopy as an essential competence for those providing care for glaucoma patients.28 We acknowledge that gonioscopy is a difficult skill to acquire and is also subjective in interpretation. The four consultant ophthalmologists at Peterborough reached a consensus that Van Herick's assessment is accurate and a more easily taught technique when compared with gonioscopy, which correlates well with gonioscopic angle assessment.21, 22, 23 Van Herick's peripheral anterior chamber depth assessment was therefore incorporated into the study at this stage, somewhat controversially, in preference to SOG performing gonioscopy, which was excluded. Some studies suggested that Van Herick's technique correlates more closely with occludable angles than direct gonioscopy when compared using high-resolution anterior segment OCT.16, 17 Patients had direct gonioscopy in the HES when judged appropriate by the ophthalmologist. To comply with the new NICE guidelines, we have started training the SOGs on gonioscopy.

The researchers also reached consensus that at this stage digital monoscopic optic disc photographs would be sufficient for optic nerve head analysis on the grounds that the view attained from the monoscopic view of the optic nerve is comparable to the view attained from the common and well-established practice of optic nerve assessment through undilated pupils,24 in which stereoscopic view is compromised.29 The SOG did not enter into discussions with the patients regarding their findings lest the opinion should differ significantly from that of the consultant. All patients were aware of this non-disclosure protocol. The appropriateness of implementation of such non-disclosure in other hospitals is debatable and depends upon the opinion of consultants in those hospitals.

The average waiting time from referral to SOG assessment was 36 days. The large standard deviation of waiting times was at least partially as a result of the long waits of few patients at the beginning of the project. The fiscal issues, including an evaluation of effectiveness and cost effectiveness in comparison with ‘traditional’ HES clinic attendance relating to this scheme, are under continued review and will be addressed in future publications.

All patients with newly SOG-diagnosed glaucoma and who had been commenced on treatment were reviewed at the hospital eye service at 3 months after second SOG appointment. Similarly, patients with poor IOP control (ie, IOP above target pressure), evidence of progression of glaucoma, and poor vision (ie, visual acuity worse than 6/36) were also referred back to the HES (Table 1). In all cases the SOG received direct critical feedback providing continual education and supervision by the project lead. Those SOGs who attain consistently high degree of agreement (⩾85%) with the project lead would proceed to the next phase (phase 2), which will be described in a future publication.

The majority of patients (96%) were satisfied with our scheme as shown in Table 4. Currently, the five SOG premises are situated in geographically disparate areas in the locale to ensure even population coverage. Patients can choose from six SOGs and flexible appointments including evenings or weekends. Of the 1184 patients seen between February 2005 and March 2007, we observed a low level of disagreement between the SOG findings compared with those of the lead consultant in most parameters analysed.

To introduce a scheme similar to the one described in this study, the researchers appreciate that a significant capital and personal investment is required. Along with equipping optometrists’ practices, enormous commitment from the HES, SOGs, GPs, and Primary Care Trust is essential to achieve the success that they believe has been achieved and is described in this paper. The scheme has reduced waiting time for new referrals, provided early treatment for those in need, and helped liberate HES resources. They believe that for this scheme to be successful, it should be continued to be led by the HES, because this will best allow for incorporation of quality assurance methodology. There should be highly committed team members at every level of patient care, including eye professionals, administration, and management teams as well as primary care contractors, along with channels for good communication. Four SOGs left the scheme. This has resulted in wastage of resources and time in training these SOGs. But they believe that some amount of wastage is to be expected of any such scheme and this fact needs to be thought through while implementing such schemes. The average consultation time for SOGs was 40 min for each patient, in comparison to an average of 20 min per HES glaucoma patient. This was due to the fact that all these patients required digital fundus photo through dilated pupil visual field assessment and filling audit sheet was extensive. They believe that, with experience, SOGs could reduce this time.

Glaucoma is a blinding disease. The lead role in the management of this serious debilitating condition should remain with the ophthalmologists. It should be noted that an element of clinical responsibility will rest with SOGs for the care and any interventions that they provide. Increasing patient numbers have, through necessity, stimulated alternative strategies in glaucoma management. They believe that specialist optometrists can be safely delegated the task as they are trained specifically in glaucoma to accept, with HES backup, a basic but significant level of responsibility in the early diagnosis and treatment of selected glaucoma and glaucoma at-risk patients.

On the basis of their experience, they believe that the commissioning of specialist optometrists in glaucoma (SOGs), under close supervision from HES, may be a viable alternative to in-house glaucoma care for selected patients, provided that it can be established and sustained in a quality-assured and cost-effective manner. Further long-term assessment of the project, and multicentre prospective studies could provide more information about advantages and disadvantages of this type of scheme.

References

Rudnicka A R, Mt-Isa S, Owen C G, Cook DG, Ashby D . Variations in primary open-angle glaucoma prevalence by age, gender, and race: a Bayesian meta-analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006; 47: 4254–4261.

Harrison RJ, Wild JM, Hobley AJ . Referral patterns to an ophthalmic out patient clinic by general practitioners and ophthalmic opticians and role of these professionals in screening for ocular disease. BMJ 1988; 297: 1162–1167.

Bowling B, Chen SDM, Salmon JF . Outcomes of referrals by community optometrists to a hospital glaucoma service. Br J Ophthalmol 2005; 89: 1102–1104.

Bell RWD, O’Brien C . The diagnostic outcome of new glaucoma referrals. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 1997; 17: 3–6.

Theodossiades J, Murdoch I . Positive predictive value of optometrist initiated referrals for glaucoma. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 1999; 19: 62–67.

Gray SF, Spry PGD, Brookes ST, Peters TJ, Spencer IC, Baker IA et al The Bristol shared care glaucoma study: outcome at follow up at 2 years. Br J Ophthalmol 2000; 84: 456–463.

Department of Health. First Report of the National Eye Care Services Steering Group 2004. Department of Health: London.

Quigley HA, Broman AT . The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol 2006; 90 (3): 262–267.

Leske MC, Heijl A, Hussein M, Bengtsson B, Hyman L, Komaroff E et al Factors for glaucoma progression and the effect of treatment, the early manifest glaucoma trial. Arch Ophthalmol 2003; 121: 48–56.

Spry PGD, Spencer IC, Sparrow JM, Peters TJ, Brookes ST, Gray S et al. The Bristol Shared Care Glaucoma Study: reliability of community optometric and hospital eye service test measures. Br J Ophthalmol 1999; 83: 707–712.

Henson DB, Spencer AF, Harper R, Cadman EJ . Community refinement of glaucoma referrals. Eye 2003; 17: 21–26.

Banes MJ, Culham LE, Crowston JG, Bunce C, Khaw PT . An optometrist's role of co management in a hospital glaucoma clinic. Ophthal Physiol Opt 2000; 20: 351–359.

Vernon SA . Shared Care in Glaucoma, Glaucoma forum, Spring, Issue 5, pp 12-13, IGA: London.

Vernon SA, Ghosh G . Do locally agreed guidelines for optometrists concerning the referral of glaucoma suspects influence referral practice? Eye 2001; 15: 458–463.

Delgado MF, Nguyen NT, Cox TA, Singh K, Lee DA, Dueker DK et al American Academy of Ophthalmology, Ophthalmic Technology Assessment Committee 2001–2002 Glaucoma Panel.##Automated perimetry: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2002; 109 (12): 2362–2374.

Baskaran M, Oen FT, Chan YH, Hoh ST, Ho CL, Kashiwagi K et al Comparison of the scanning peripheral anterior chamber depth analyzer and the modified van Herick grading system in the assessment of angle closure. Ophthalmology 2007; 114 (3): 501–506.

Kashiwagi K, Tokunaga T, Iwase A, Yamamoto T, Tsukahara S . Agreement between peripheral anterior chamber depth evaluation using the van Herick technique and angle width evaluation using the Shaffer system in Japanese. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2005; 49 (2): 134–136.

Banes MJ, Culham LE, Bunce C, Xing W, Viswanathan A, Garway-Heath D . Agreement between optometrists and ophthalmologists on clinical management decisions for patients with glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2006; 90 (5): 579–585.

Azuara-Blanco A, Burr J, Thomas R, Maclennan G, McPherson S . The accuracy of accredited glaucoma optometrists in the diagnosis and treatment recommendation for glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2007; 91: 1639–1643.

Gordon Bennett PS, Ioannidis AS, Papageorgiou K, Andreou PS . A survey of investigations used for the management of glaucoma in hospital service in the United Kingdom. Eye 2008; 22: 1410–1418.

Foster PJ, Devereux JG, Alsbirk PH, Lee PS, Uranchimeg D, Machin D et al Detection of gonioscopically occludable angles and primary angle closure glaucoma by estimation of limbal chamber depth in Asians: modified grading scheme. Br J Ophthalmol 2000; 84: 186–192.

Nolan WP, Aung T, Machin D, Khaw PT, Johnson GJ, Seah SK et al Detection of narrow angles and established angle-closure in Chinese residents of Singapore. Am J Ophthalmol 2006; 141: 896–901.

Herick WV, Shaffer RN, Schwartz A . Estimation of width of angle of anterior chamber. Incidence and significance of the narrow angle. Am J Ophthalmol 1969; 68: 626–629.

Garaway Heath DF, Hitchings RA . Quantitative evaluation of the optic nerve head in early glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 1998; 82 (4): 352–361.

Johnson ZK, Griffiths PG, Birch MK . Nurse prescribing in glaucoma. Eye 2003; 17 (1): 47–52.

Bengtsson B, Heijl A . SITA Fast, a new rapid perimetric threshold test: description of methods and evaluation in patients with manifest and suspect glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 1998; 76: 431–437.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Glaucoma: diagnosis and management of chronic open angle glaucoma and ocular Hypertension. Clinical guidelines CG85, UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines, April 2009.

Leibowitz HM, Krueger DE, Maunder LR . The Framingham Eye Study Monograph. Surv Ophthalmol 1980; 24 (Suppl): 335–610.

Parkin B, Shuttleworth G, Costen M, Davison C . A comparison of stereoscopic and monoscopic evaluation of optic disc topography using a digital optic disc stereo camera. Br J Ophthalmol 2001; 85: 1347–1351.

Acknowledgements

We thank NHS Modernisation Agency, A Kent, H McLeod, S Westwood, S Broome, S Urquart, G Sondh, C Pirrie, N Guttridge-Smith, A Clark, M Manak, R Whitehead, C Love, M A Omar, J Winder, J Avery, B Stevenson, P Gorst, S Westwood, A Stone, S Cumley, R Heywood, J Nair, P Alexander, G Lewis, S Hodnett, S Sood, R Adams, Peter Murray, and the nursing staff of Peterborough eye department. This project was funded by the UK Department of Health through the Modernisation Agency as one of the selected pilot sites to develop a model for a glaucoma care pathway.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This paper was presented as a poster at the 2006 annual congress of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists and as a presentation and poster at the Oxford Congress 2007

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Syam, P., Rughani, K., Vardy, S. et al. The Peterborough scheme for community specialist optometrists in glaucoma: a feasibility study. Eye 24, 1156–1164 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2009.327

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2009.327

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Providing capacity in glaucoma care using trained and accredited optometrists: A qualitative evaluation

Eye (2023)

-

Defining stable glaucoma: a Delphi consensus survey of UK optometrists with a specialist interest in Glaucoma

Eye (2021)

-

Care pathways for glaucoma detection and monitoring in the UK

Eye (2020)

-

Systematic review of the appropriateness of eye care delivery in eye care practice

BMC Health Services Research (2019)

-

A technician-delivered ‘virtual clinic’ for triaging low-risk glaucoma referrals

Eye (2017)