Abstract

Purpose

To determine the frequency of haemorrhagic pigment epithelial detachment (PED) among patients presenting with either polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV) or choroidal neovascularization (CNV) and calculate the degree to which the presence of a haemorrhagic PED can be used to predict the diagnosis of PCV.

Methods

A retrospective review of 290 eyes of 253 patients presenting to the Singapore National Eye Centre with serosanguineous maculopathy. Patients underwent ophthalmologic examination including digital colour fundus photography and stereoscopic fluorescein angiography and indocyanine green angiography (ICGA). Classification into PCV or CNV was based on ICGA findings, and presence or absence of haemorrhagic PED was documented.

Results

In total, 138 eyes of 123 patients were diagnosed with PCV and 152 eyes of 130 patients with CNV. A haemorrhagic PED was a significantly more common (P<0.001) presenting feature in PCV eyes (63, 45.7%) than CNV eyes (6, 3.9%) (odds ratio (OR) 20.4, 95% confidence interval (CI) 8.5–49.4). Age-related maculopathy was found significantly more frequently (P<0.001) in the unaffected fellow eye of CNV patients (57, 52.8%) than PCV patients (28, 22.8%) (OR 3.2, 95% CI 1.8–5.7).

Conclusions

In patients of Chinese ethnicity, a haemorrhagic PED is significantly more likely to be the presenting feature of PCV than CNV. Patients presenting with this clinical feature should make the clinician suspicious of an underlying diagnosis of PCV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stern et al1 described a new clinical condition characterized by recurrent, multiple, bilateral, asymmetric, serosanguineous retinal pigment epithelial detachments (PEDs) in 1985. Yannuzzi et al2 subsequently suggested the term idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV) in their description of a series of 11 patients with polypoidal, subretinal, vascular lesions associated with multiple, recurrent, serosanguinous detachments of the retinal pigment epithelium and neurosensory retina.

PCV has been described as a distinct clinical entity, differing from neovascular or wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and other macular diseases associated with subretinal neovascularization. However, it is still a matter of controversy as to whether or not PCV represents a subtype of wet AMD.3 Characteristic clinical features earlier described include vitreous haemorrhage, absence of drusen, and minimal fibrous scarring.4 We have noticed an increased frequency of patients in our population diagnosed with PCV presenting with a haemorrhagic PED. We, therefore, wished to determine the frequency of PCV and choroidal neovascularization (CNV) patients presenting to our department with haemorrhagic PED and calculate the degree to which this clinical feature could be used to predict the diagnosis of PCV.

Materials and methods

A retrospective study of 253 patients of Chinese ethnicity presenting to the Vitreoretinal Department of the Singapore National Eye Center with serosanguineous maculopathy between January 2002 and December 2007 was carried out. The study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethics approval was obtained from the Singapore Eye Research Institute Review Board.

All patients underwent a comprehensive ophthalmologic examination, digital colour fundus photography and stereoscopic fluorescein angiography (FA) and indocyanine green angiography (ICGA). Exclusion criteria included significant co-morbidity that could confuse the clinical picture such as retinal vascular occlusion, uveitis, trauma-related eye disease, or other neovascular maculopathies such as angioid streaks and high myopia or media opacities preventing adequate fundal examination and photography.

The patients were classified as either CNV or PCV lesions. The diagnosis of PCV was made according to the Japanese Study Group guidelines published in 2005.5 Clinical features of patients with PCV included the presence of subretinal red or orange nodules and haemorrhagic PED by fundus examination and characteristic saccular vascular abnormalities in the inner choroid as visualized on ICG angiography. Evaluation and classification of lesions were performed by at least two retinal-fellowship trained ophthalmologists. Equivocal cases were not included and, therefore, this study includes only clearly defined CNV or PCV lesions. Patients with a combination of PCV and CNV lesions were not included in this study.

ICGA in the majority of circumstances is able to image PCV even in the presence of heavy blood obscuring the fundus. Angiography was, therefore, performed without delay so that relevant treatments could be initiated. Very occasionally, however, no lesion could be identified on the angiogram, and under these circumstances, it was necessary to repeat the angiography as the blood cleared to identify any components to the vascular abnormality, which had earlier been obscured.

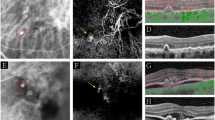

The presence of a haemorrhagic or serous PED was documented (Figures 1 and 2). Age-related maculopathy (ARM) in the unaffected fellow eye was also determined after the Wisconsin Age-Related Maculopathy grading system as described elsewhere.6 Although disciform scarring is reported to be uncommon in PCV,7 inactive macular lesions without active exudation were not included in the classification and, therefore, disciform scars were not evaluated as either CNV or PCV.

Fisher's exact χ2 statistical test was used for categorical variables and student's t-test was used for continuous variables.

Results

In total, 138 eyes of 123 patients were diagnosed with PCV and 152 eyes of 130 patients were diagnosed with CNV. The mean age of PCV patients (68.3 years (standard deviation (SD) 8.1) was significantly lower (P<0.001) than that of CNV patients (73.0 years (SD 8.5) P<0.001. Of these PCV patients, 77 (62.4%) were men and 87 (66.9%) of CNV patients were men. There was no significant difference between the sex distribution between PCV and CNV. Table 1 shows the patient demographics and characteristics of PCV and CNV in this study.

A haemorrhagic PED was a significantly more common (P<0.0001) presenting feature in PCV eyes (63, 45.7%) than in CNV eyes (6, 3.9%) (odds ratio (OR) 20.4, 95% confidence interval (CI) 8.5–49.4). Only 7 (5.0%) of PCV and 10 (6.6%) of CNV patients presented with a large serous PED and there was no significant difference between the two groups. 15 (12.2%) patients were found to have bilateral PCV and 22 (16.9%) CNV patients had bilateral CNV and again there was no significant difference between the two groups. ARM was found significantly more frequently (P<0.001) in the unaffected fellow eye of CNV patients (57, 52.8%) than PCV patients (28, 22.8%) (OR 3.2, 95% CI 1.8–5.7). Table 2 shows the presenting features of PCV and CNV in relation to the presence of PED in this study.

Discussion

The mean age of patient with PCV in our study was 68.3 years, which was significantly lower (P<0.0001) than that of CNV (73.0 years). Other studies in Caucasians and Asians, however, do not report a significant difference in age of presentation between PCV and CNV.8, 9, 10 Both PCV and CNV groups showed a higher preponderance of males, which is comparable to other studies of serosanguineous maculopathy in Asians.8, 9 Absence of drusen in the fellow eye is a recognized feature of PCV.4 In our study, ARM was found in the unaffected fellow eye in significantly more patients with CNV than PCV (P<0.001). This confirms the findings from other studies and suggests that the underlying pathogenesis of PCV may be different from CNV.

Serosanguineous PEDs are one of the clinical characteristics of PCV.2, 11, 12 In our study, 51% of eyes with PCV presented with any form of PED (haemorrhagic or serous). Tsujikawa et al11 report a PED frequency of 53% in their study in Japanese patients with PCV. Scassellati-Sforzolini et al10 showed a lower rate (26.3%) of PED in Italians with PCV, although they restricted classification to >2 disc areas. Importantly, Ahuja et al12 reported in their study that 85% of eyes with large serosanguineous PEDs in the absence of drusen showed polypoidal lesions on ICGA.

The serosanguineous PEDs seen in PCV may be either serous or haemorrhagic in nature.11, 12, 13 Tsujikawa et al11 showed that the majority of PEDs in PCV were serous. This is, however, in contrast to our study in which the PEDs were predominantly haemorrhagic and were the presenting feature in 45.7% of eyes diagnosed with PCV.

The rate of haemorrhagic PED in our study was significantly higher than that found with CNV (P<0.0001). The OR of a patient presenting with a haemorrhagic PED being subsequently diagnosed with PCV is approximately 20 in our study. The diagnosis of PCV is best made using ICGA, as it allows visualization of choroidal vasculature after the initial transit of dye.12, 14 ICGA is a relatively expensive investigation compared with FA and in many parts of the world is not a routine investigation for patients presenting with serosanguineous maculopathy especially in those in which PCV is seen with reduced frequency such as Europe and the United States.10, 15, 16 Our findings suggest that a diagnosis of PCV is highly likely in the presence of a haemorrhagic PED and we would, therefore, advocate the use of ICGA to investigate those patients presenting with this clinical feature on fundoscopy, especially in those of Chinese ethnicity.

In summary, the demographics of PCV and CNV in this study are comparable to other Asian studies of serosanguineous maculopathy, although in our population PCV seems to present at a younger age than CNV. A haemorrhagic PED was found significantly more frequently in eyes with PCV than CNV. Patients presenting with this clinical feature should make the clinician highly suspicious of a diagnosis of PCV, and we would recommend the use of ICGA to investigate patients under these circumstances to identify any underlying polypoidal lesions.

References

Stern RM, Zakov ZN, Zegarra H, Gutman FA . Multiple recurrent serosanguineous retinal pigment epithelial detachments in black women. Am J Ophthalmol 1985; 100 (4): 560–569.

Yannuzzi LA, Sorenson J, Spaide RF, Lipson B . Idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (IPCV). Retina 1990; 10 (1): 1–8.

Kondo N, Honda S, Ishibashi K, Tsukahara Y, Negi A . Elastin gene polymorphisms in neovascular age-related macular degeneration and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008; 49 (3): 1101–1105.

Ciardella AP, Donsoff IM, Yannuzzi LA . Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Ophthalmol Clin North Am 2002; 15 (4): 537–554.

Japanese Study Group of Polypoidal Choroidal Vasculopathy. Criteria for diagnosis of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi 2005; 109 (7): 417–427.

Klein R, Davis MD, Magli YL, Segal P, Klein BE, Hubbard L . The Wisconsin age-related maculopathy grading system. Ophthalmology 1991; 98 (7): 1128–1134.

Yannuzzi LA, Ciardella A, Spaide RF, Rabb M, Freund KB, Orlock DA . The expanding clinical spectrum of idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 1997; 115 (4): 478–485.

Maruko I, Iida T, Saito M, Nagayama D, Saito K . Clinical characteristics of exudative age-related macular degeneration in Japanese patients. Am J Ophthalmol 2007; 144 (1): 15–22.

Liu Y, Wen F, Huang S, Luo G, Yan H, Sun Z et al. Subtype lesions of neovascular age-related macular degeneration in Chinese patients. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2007; 245 (10): 1441–1445.

Scassellati-Sforzolini B, Mariotti C, Bryan R, Yannuzzi LA, Giuliani M, Giovannini A . Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in Italy. Retina 2001; 21 (2): 121–125.

Tsujikawa A, Sasahara M, Otani A, Gotoh N, Kameda T, Iwama D et al. Pigment epithelial detachment in polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 2007; 143 (1): 102–111.

Ahuja RM, Stanga PE, Vingerling JR, Reck AC, Bird AC . Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in exudative and haemorrhagic pigment epithelial detachments. Br J Ophthalmol 2000; 84 (5): 479–484.

Yuzawa M, Mori R, Kawamura A . The origins of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 2005; 89 (5): 602–607.

Destro M, Puliafito CA . Indocyanine green videoangiography of choroidal neovascularization. Ophthalmology 1989; 96 (6): 846–853.

Lafaut BA, Leys AM, Snyers B, Rasquin F, De Laey JJ . Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in Caucasians. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2000; 238 (9): 752–759.

Yannuzzi LA, Wong DW, Sforzolini BS, Goldbaum M, Tang KC, Spaide RF et al. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy and neovascularized age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 1999; 117 (11): 1503–1510.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Drs Ranjana Mathur, Jacob Cheng, Chui Ming Gemmy Cheung, Adrian Koh, Lee Shu Yen, Bobby Cheng, Edmund Wong, Yeo Kim Teck, Ronald Yeoh and Professors Ang Chong Lye and Ong Sze Guan who all contributed cases to this study. This study was supported by Singhealth Grant SHF/FG381P/2007.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cackett, P., Htoon, H., Wong, D. et al. Haemorrhagic pigment epithelial detachment as a predictive feature of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in a Chinese population. Eye 24, 789–792 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2009.214

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2009.214

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Polypoidal Choroidal Vasculopathy

Current Ophthalmology Reports (2019)

-

Six-month visual prognosis in eyes with submacular hemorrhage secondary to age-related macular degeneration or polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2013)