Abstract

Purpose

To report a new phenotype with additional data on the oculo–dental syndrome of cone-rod dystrophy (CRD) and amelogenesis imperfecta (AI) caused by mutations on CNNM4, a metal transporter, with linkage at achromatopsia locus 2q11 (Jalili syndrome).

Methods

Three siblings aged 5, 6, and 10 years from a six-generation Arab family in Gaza City underwent full systemic, ophthalmic, and dental examinations, investigations and detailed genealogy.

Results

Subjects presented at early childhood with visual impairment and abnormal dentition together with photophobia and fine nystagmus increasing under photopic conditions, in the presence of normal fundi. Electrophysiologically, photopic flicker responses were impaired; scotopic responses were extinguished at the age of 10 years. Anterior open bite accompanied AI in all siblings. The syndrome formed 83% of CRD cases in the Gaza Strip, which has a prevalence of 1 : 10 000.

Conclusion

On the basis of clinical features and electrophysiology, two phenotypes exist: an infancy onset form with progressive macular lesion and an early childhood onset form with normal fundi. More prevalent than previously thought, Jalili syndrome presents a model of the effect of different mutations of the same genetic defect, observations of the same phenotype at different stages of the natural history of the disease, and the influence of epigenetic and tissue-specific factors as causes of phenotypic variability. The paper calls for action to tackle consanguinity in endogamous communities, addresses the possible role of high fluoride levels in groundwater as a trigger for genetic mutations, and the use of red-tinted filter in cone disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cone-rod dystrophies (CRDs) are part of a wide spectrum of progressive photoreceptor disorders becoming known collectively as retinal ciliopathies.1, 2 Photoreceptor dystrophies are categorised on the basis of the photoreceptor cells primarily involved in the disease process as depicted by electrophysiology. Within this spectrum, three main groups are recognised; cone-rod, rod-cone, and mixed receptors dystrophies. In the former (CRD), cones are the cells predominately involved in the disease process, at least initially.3, 4, 5 Rod-cone dystrophies (RCD) form the other end of this spectrum whereby rods are the primarily affected cells, the term retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is now commonly reserved for this latter group.6, 7 In between lie rarer and more complex clinical entities, mixed receptors dystrophies, in which both photoreceptor types are severely compromised from onset. The commonest entity in the latter is Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) in which night blindness, as initially described by Leber, is an important feature.8, 9 More recently, less recognised conditions with photophobia from different genetic mutations have been included under the term LCA,10 although the term congenital amaurosis of the cone-rod (CACR) was suggested as an alternative for this subgroup to identify them as separate clinical entities.11 Retinal ciliopathies can occur as isolated retinal conditions or in combination with other ciliopathies, which encompass ectodermal, cerebrorenal, and metabolic disorders and are caused by a wide array of genetic mutations.1, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28

Hereditary amelogenesis imperfecta (AI) is a fairly common group of generalised enamel disorders, inherited as autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or X-linked traits, affecting both primary and secondary dentition. It can manifest in isolation or as part of syndromatic disorders. Depending on the timing of the disturbance at embryonic development two main types exist, a hypoplastic and a hypomineralised. The hypoplastic type results from disturbances at the secretory stage of matrix formation leading to deficient matrix and thin hypoplastic enamel. Hypomineralised AI is the outcome of impairment at the maturation stage of enamel formation. Both types can overlap and there is no agreed method of classification.29 AI is diagnosed on the basis of the structural and morphological abnormalities in the enamel. Genetic anterior open bite (AOB), a form of malocclusion, is skeletal in origin and has been reported in both types of AI.30, 31 AI has also been described in association with other eye conditions including RP,32 oculo–dentodigital dysplasia with microphthalmia,33 iris coloboma,34 myopia,35 and other abnormalities of the ocular adnexa.36

The recessive oculo–dental syndrome of CRD and AI (OMIM 217080) was identified by the author during blind schools survey between 1985 and 1987 in 34 patients from three families from the Gaza Strip (GS). The condition in 29 patients (first extended Gaza family described type A (Gaza A)) from an extended family was reported first.37 Clinical features of the second family (family reported in this paper type B (Gaza B)), which exhibited a different phenotype and an additional singleton, have not been published previously. A linkage at the achromatopsia locus on chromosome 2q11 with the causative gene residing in the same chromosomal region (2q) was established.38 Recently, the syndrome has been reported in several other ethnically diverse families in different world regions with different mutations on CNNM4, a metal transporter gene, and the name Jalili syndrome proposed. This finding establishes a connection between tooth biomineralisation and retinal function and the roles of metal transport in these processes.14, 15, 39

Materials and methods

Three siblings, two females aged 5 and 6 and a male aged 10 years from a six-generation Arab family living in Gaza City (Gaza B, Figure 1: VI:1, VI:5, and VI:6) first presented to the author as part of 18 sibships who shared an oculo–dental association (pupils at UNRWA School for the Blind, Gaza City) in the course of a blind schools survey between 1985 and 1987 (http://jalili.co/covi/). Full ophthalmic, systemic, and dental examinations together with psychophysical and electrophysiological tests were performed. The latter included full-field electroretinography (ERG), electro-oculography (EOG), and visual evoked potentials (VEPs). In the eldest, kinetics perimetry using Goldman's field analyser and fluorescein angiography (FFA) were also undertaken. The full methodology and ERG protocol are described elsewhere.37, 40 Comprehensive family interviews delineating all family relationships, reliant on the strong oral tradition of family genealogy held by family members and the elders, were carried out to establish relatedness and identify genetic families. Additionally, the siblings were tested for functional and symptomatic improvement with red-tinted glasses; also their educational abilities using school marks as a crude parameter were assessed in comparison with other blind schools children. Blood samples for molecular studies were taken from all family members. The findings were compared with 30 patients (17 sibships) from two other Gaza families with the syndrome with additional unpublished data. Prevalence given was based on under 19 years old population of 322 000, 562 300, and 884 400 populations in the GS, the West Bank (WB) and both Palestinian regions combined respectively at the time of the survey.

Results

Demography and consanguinity

Parents (Figure 1: V:9, V:10) were second cousins living in Gaza City. Grandfather I:1 came from Egypt to Barbara village (population 2410, entirely Arab, in 1945) 17 km northeast of Gaza City, currently Mavki'im near Ashkelon, marrying a local Palestinian (I:2). (Supplementary Figure S1) (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barbara,_Gaza, accessed December 2009). Pedigree chart analysis of this family suggests the genetic mutation occurred either in the first generation (Figure 1: I:1/I:2) or in the second (Figure 1: II:3/II:4). The extended Gaza B family was highly inbred with other reported genetic conditions including individual cases of mental subnormality, ptosis, and buphthalmos being said to exist (Figure 1: IV:8, IV:12, and V:4).

Ophthalmic findings

The eldest two siblings presented with visual difficulties between 5 and 6 years of age and the youngest with the dental anomaly at the age of 3 years (Table 1). Corrected visual acuities indoor with Snellen chart were 2/60, 5/60, and 6/60 in the 5, 6, and 10 years old siblings, respectively, only fractionally better than unaided acuity. This was consistent over 18 months follow-up period. Near acuity was N8 in the youngest sibling and N12 in the eldest. All affected siblings had 2–4 dioptres of hypermetropia. Visual acuities varied with the levels of illumination, being more compromised under outdoor, bright daylight illumination. Photophobia was marked causing habitual orbicularis spasm. All siblings denied night blindness, which was confirmed by observing their navigational abilities in dim light.

Fine nystagmus was detected in the two eldest siblings increasing in amplitude under bright outdoor illumination. In the youngest, nystagmus was latent, manifested only under bright conditions. The eldest had slight latent deviation for both near and distance with diplopia experienced before recovery together with a tendency to deviate on elevation. None of the patients had suppression. Colour vision was absent in all cases. Anterior segments were normal as were pupillary reactions.

Fundi appeared normal with minor retinal epithelial defects at the periphery in the eldest confirmed by FFA (Figure 2b). A few vitreous cells were present in all siblings. Peripheral fields with Goldman perimetry were full in the eldest; the youngest two sisters had no peripheral contraction by the confrontation method.

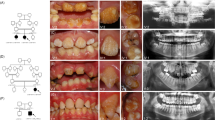

Type 2 CRDCRD and AI (Jalili syndrome). Upper row (a, b): fundus photographs and angiogram of the 10 years old siblings; (c) 5 years youngest sister with phenotype B Jalili syndrome showing normal looking macula and absence of peripheral pigmentary proliferation. Second row (d–f): AI in the 10, 6, and 5 years old siblings respectively; (d) staining and calculus formation in the upper teeth, note pitting from nut cracking, and irregular dentition in the lower teeth; (e) marked calculus formation and AOBs in the 6 years old sister; (g) AOB without staining or calculus formation in the youngest sister. Third row (j–i) evolution of macular lesions in phenotype A (Gaza A). (j) Bulls eye lesion becoming more confluent with eventual chorioretinal atrophy and excavation (enlarged in inset); (i) macular coloboma (posterior staphyloma) of sibling C, note the remnant of posterior hyaloid artery at 8 o'clock position. Fourth row (j–l) retina in members of Gaza A genetic family from different patrilineal. (j) Flat atrophic macular degeneration (inset macula from a different sibling); (k1) peripheral pigmentary clumping; (k2) slightly different AI morphology in these siblings. Fifth row (m–o) evolution of dental lesions in AI. (m) Teeth are initially pitted; (n) further loss of enamel and staining; (o) eventual loss of teeth.

Electrophysiology

Cone responses (flicker) were grossly impaired in the youngest sibling, barely recordable in the middle, and totally extinguished in the eldest. Rod responses to low-intensity blue light were flat in all the siblings but were recordable with high-intensity blue and white light stimuli. These were significantly reduced in the youngest two siblings and extinguished in the eldest brother (Figure 3). EOG showed grossly reduced Arden ratios (Table 1). VEP responses were normal.

Dental findings

AI was associated with AOB and small premaxilla in all the three siblings. Various degrees of decay were present and the eldest brother had a significant degree of calculus formation. Figures 2m–o depict the natural history of dental changes in Jalili syndrome.37

General aspects

Siblings were otherwise healthy with no other associated medical conditions. They were educationally normal and scored above average in their school marks. They all benefited from plain glass red-tinted filter with significant increase in comfort, improvement of photophobia, and enhanced contrast sensitivity. The latter had an appreciable impact on their image perception, particularly outdoors (http://jalili.co/covi/redfilter.pdf).

Discussion

Two clinical phenotypes exist in this syndrome. The three siblings reported in this paper differ from those reported initially in type A (Gaza A) in presentation, fundus appearance, speed of loss of rod responses, and the association of AOB with AI in all the siblings.37

Genetic epidemiology

The finding of different mutations in the CNNM4 gene causing the syndrome has confirmed the unrelatedness of the two Gaza families (Gaza A and B) whose origin differed with no traceable intermarriage found between them. In Gaza B, the male founder was Egyptian marrying a local villager from Barbara village in Palestine. The ancestor of Gaza A was traced back to the Arabian Peninsula (http://jalili.co/covi/ft_gazaa.pdf). The suspected founder of the genetic mutation in Gaza B was the fourth grandson of a man who had originally moved from Mekka in Hijaz (present day Saudi Arabia) and settled in Salama village near Jaffa, now Kafr Shalem, marrying into the indigenous population. The family moved after 1948 to the eastern part of Khan Yunis (Younis) (Wikipedia.Khan Yunis. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khan_Yunis, accessed December 2009) where they were scattered in several nearby villages and hamlets such as Khirbat Ikhza'a, Beni Salama, and Abassan. (Supplementary Figure S1) Other sibships with affected siblings had emigrated to Libya and other Arab countries.

The founders of Gaza C family had moved from Bir Shiva to their current location in Rafah on the Egyptian border post-1967. Although there was evidence of intermarriage between the extended family of the singleton C and the extended Gaza A family, it was not possible to ascertain a direct linkage that would account for singleton C being part of the genetic Gaza A family (http://jalili.co/covi/ft_gazac.pdf) (unpublished data).

Jalili syndrome was only found in the GS with no other cases detected in the WB. These communities are highly inbred41 with 95% (17/18 sibship) consanguinity rate in the affected sibships (first cousins, 8; second cousins, 6; and third cousins, 3). Gaza A's multiple sibships created a preponderance of cases, which constituted 83% of the total cases of progressive cone degeneration in the GS (unpublished data). Among the recently reported cases eight are homozygous and two are heterozygous from genetic isolates.14, 15

Socioeconomic factors combined with social custom have accentuated the high level of inbreeding, increasing in the younger generations, and causing the explosion of large numbers of cases in Gaza A family.41 This was compounded by the state of isolation caused by geopolitical factors together with social stigmatisation faced by these families, thus deterring marriages other than between very close cousins. The strong tribal bond is well demonstrated by the marriage between a mentally subnormal member of the family to a normal female second cousin, the grandparents (Figure 1; IV:8 and IV:9) of the three siblings of Gaza B. Additionally, the severe state of economic deprivation of all the families denied the affected members any effective dental treatment and denied access to visual aids. There is a great need to tackle consanguinity in the endogamous communities in many developing countries.

The prevalence of progressive cone degenerations (predominantly CRD) in the GS in 1986–1987 was 1 : 10 000 vs 1 : 26 000 in the WB (average 1 : 18 500 in both regions combined) (unpublished data). Epidemiological studies on the prevalence of these conditions are scarce. Gaza prevalence figure is significantly higher than the reported prevalence of 1 : 40 000.5 To the best of the author's knowledge, this is the highest reported prevalence of CRDs. The published prevalence of AI ranges between 1 : 700 and 1 : 14 000,31, 42, 43 however, figures are unavailable on its prevalence among the population in the region.

Clinical aspects

The combination of photophobia and dental anomaly is the hallmark of this syndrome in both types. In type B (this paper), ocular features were milder and of later onset than in type A presenting at early childhood. Type A was detected in early infancy and could have been present at birth as the youngest sibling aged 3 months had a well-formed bull's eye lesion.37 Night blindness was denied in all Gaza cases but was present in the other reported cases.14, 15, 39 The absence or lack of significance of night blindness in some cases of CRD is well documented and in others it developed only when the visual field became <10 degrees; no explanation, however, has been given for this phenomenon.5, 6, 44 The speed of scotopic ERG loss also differed. In type B, rod ERG became extinguished by the end of the first decade of life whereas in type A rod responses remained recordable until the late teens/early twenties.37

The degree of scotopic ERG loss also correlates with those found in the red-tinted filter trial whereby advanced cases of CRD with well-established pigmentary proliferation responded less to red filter than those with earlier disease CRD, cone dystrophies, and achromatopsia (unpublished data). The merits of red-tinted filters in symptomatic relief of photophobia and increasing contrast sensitivity were ascertained in all cases with cone disorders. There was considerable, though variable, symptomatic relief as opposed to using standard commercially available ultraviolet absorbing brown and grey glasses; this was confirmed in later studies.45 The use of red-tinted contact lenses incorporating the refractive error was not practicable because of both the patient's environment and the socioeconomic deprivation of these families. Further work to evaluate the benefit of refractive, red-filtered contact lenses in the management of cone dystrophies including achromatopsia is recommended.

It is difficult to explain the significance of the better distance visual acuity with increasing age of the three siblings and whether this was a genuine improvement with age or because of other factors such as increased discipline at examination with age, part of intrafamilial variability in the severity of the visual loss, or related to the deterioration of rod function. It is interesting to note that the acuities in the 7–13 years age cohort (13/34 patients) in the total Gaza series with this syndrome averaged better than the acuities in the <7 years cohort (10/34). The acuity started to decline gradually after the age of 15 years from advancing macular degeneration in type A (11/34 cases), which also paralleled the loss of rod ERG in these cases. (Supplementary Figure S2) Near acuity in type B, however, deteriorated with age in spite of the absence of macular lesion.

Retinal phenotypes

It is not possible to ascertain whether the absence of retinal lesion is a permanent feature in this phenotype or it reflects a stage in the natural history so that macular lesions and pigmentary proliferation would eventually develop in the course of the disease. Type A displays the whole spectrum of macular lesions described in CRD ranging from bull's eye lesion in early infancy or at birth progressing to chorioretinal excavation and posterior staphyloma (coloboma) at later stages of the disease (Figures 2g–i). Although the main Gaza A genetic family followed the above natural history, there was a suggestion of patrilineal variability whereby sibships descended from fathers from outside the genetic family showed minor differences in the appearance of the macular/retinal lesions. These included retinal morphology that bore resemblance to RCD (RP) whereby macular lesions were flat and atrophic without excavation with early appearance of peripheral pigmentary clumping (Figures 2j and k). The latter subtype retained the same electrophysiological pattern of responses and absence of night blindness; their peripheral visual fields were only moderately contracted. This is in contrast to members of the same age group of the main Gaza A genetic family who had intact peripheral fields. Further molecular work is needed to establish the presence or absence of any modifying factors in influencing these phenotypic differences. Sibling C phenotype is that of type A with colobomatous macular lesion and peripheral pigmentary disturbances present at a much earlier age of 17 years (Figures 2i) than his counterpart with colobomatous lesion in Gaza A, who was 50 years of age37 (unpublished data).

Differential diagnosis

On the basis of clinical features and electrophysiology, type B was differentiated from other retinal dystrophies with normal looking fundus, photophobia, and absent colour vision, which were achromatopsia (rod monochromatism) and CACR. The achromatopsia cohort (33 cases, 12 families) was a predominantly clinically homogeneous stationary group with severe photophobia and better visual acuities ranging from 6/60 to 6/36. CACR, was an unusually severe form of mixed receptors dystrophy, which exhibited profound photophobia with total cessation of visual functions (absolute hemeralopia) under bright illumination. Vision in this condition changed from CF/navigational vision indoors and in dim illumination, to NLP combined with profound discomfort in sunlight11 (9 cases, 3 families). This contrasted to the LCA series (88 cases, 45 families) in which night blindness and comfort in bright light, with a sense of pleasure staring at the sun, was the hallmark of the condition together with the other recognised manifestations8 (unpublished data).

Type A, with its early macular lesion, was differentiated from other conditions with progressive macular lesions namely RCD and LCA, cone degenerations, and a variety of isolated macular dystrophies. Cone dystrophies lacked scotopic involvement as confirmed by serial analysis of 11 cases from 5 families between 3 and 53 years of age at various stages of the natural history of the disease (unpublished data).

Isolated macular dystrophies (24 cases), which had normal colour vision and intact full-field electrophysiology included Stargardt disease with flecked retina (6/24), juvenile atrophic type of macular dystrophy with myopia (3/24), and a rare association of a congenital-onset macular dystrophy with high myopia. The latter (six siblings) differed by their characteristic well-defined lesions starting at choriocapillaris and retinal pigment epithelium level progressing with age both in size and depth combined with progressive myopia ranging from −3.00 to −10.50 dioptres.46

Dental phenotypes

All reported cases with Jalili syndrome exhibit the same type of AI consisting of generalised mixed hypomaturation/hypoplastic form in both primary and secondary teeth, detailed description reported elsewhere (Figures 2d–f).14, 37, 39 The association of AOB and small premaxilla in Gaza B shows 100% penetrance yet it was present in only two siblings (2/30) in Gaza A with an additional sibling with posterior open bite (unpublished data). AOB was not reported in the other cases of the syndrome with CNNM4 mutations.14, 15 Malocclusion is a known association in several other syndromes.47, 48 In the blind schools survey, genetic AOB was encountered in two singletons, one with microphthalmia and a second with syndromatic musculoskeletal abnormalities with prominent canines, anterior positioning of the second toe and waddling gate (unpublished data). The natural history of AI is depicted in Figures 2m–o.

Genetic variability

It has been demonstrated that the wide intra- and interfamilial variability is caused by diverse expressions of CNNM4.14, 15 Variations in gene expression are tissue specific. Tissue-specific genes, such as photoreceptor genes, have a tendency for high expression variation, a phenomena more pronounced in the human brain of which the retina is part.49, 50 This is influenced by the dynamics of the vision process, the possible effect of different levels of disease susceptibility and other factors including second-site modifiers.51 This would explain the wider phenotypic diversity of retinal dystrophies in comparison with the dental phenotypes.

Possible cause of mutagenesis

The environs of the Gaza sibships are well recognised for their high fluoride level in groundwater causing a high incidence of dental fluorosis in the population.52 (Supplementary Figure S3) Documented levels between 1979 and 1981 (Supplementary Table S1) exceeded WHO recommended safe levels of <1 mg/l in hot climates and <1.2 mg/l in cool climates.53 The deleterious effects of high fluoride levels, which are dose dependent are well recognised.54

Fluoride has a toxic effect on mineralisation in children, during lactation and pregnancy, with an increased sensitivity during periods of heightened need for calcium. A wide range of systemic effects including impairment of development of intelligence in children have been described in regions with high fluoride intake.55 In addition, in vitro studies has shown that sodium fluoride is mutagenic in cultured mammalian cells and can induce gene-locus mutations.56 (Health effects: fluoride's mutagenicity (genotoxicity), http://www.fluoridealert.org/health/cancer/mutagen.html, accessed December 2009).

The regions and neighbouring areas where cases with Jalili syndrome are reported to come from have high levels of naturally occurring fluoride in drinking water (Supplementary Table S1).14, 15, 57 The possibility that exposure of the founders of patients with Jalili syndrome to high fluoride levels, perhaps in association with hot climate (increased water intake) and dietary deprivation (low dietary calcium), are the triggering factor inducing these genetic mutations needs to be considered and explored further. Additionally, an associated increased susceptibility to fluoride toxicity in these founders cannot be excluded.58, 59 It is of interest to note that Newfoundland, another region with a high incidence of genetic diseases,60 also has high levels of fluoride in the water in the coastal areas where the original founders had settled. (http://www.env.gov.nl.ca/env/Env/waterres/water_resources.aspm accessed January 2010). Further research is needed to explore the harmful effects of high levels of fluoride (and other toxic contaminants) of drinking water in triggering genetic mutations.

References

Adams NA, Awadein A, Toma HS . The retinal ciliopathies. Ophthalmic Genet 2007; 28 (3): 113–125.

Badano JL, Mitsuma N, Beales PL, Katsanis N . The ciliopathies: an emerging class of human genetic disorders. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2006; 7: 125–148.

Moore AT . Cone and cone-rod dystrophies. J Med Genet 1992; 29 (5): 289–290.

Traboulsi EI . Cone dystrophies. In: Traboulsi EI (ed). Genetic Diseases of the Eye. Oxford University Press: New York, 1998, pp 357–365.

Hamel C . Cone rod dystrophy. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2007; 2: 7.

Krill AE . Cone degenerations. In: Archer D (ed). Krill's Hereditary Retinal and Choroidal Diseases. Harper & Row: Hagerstown, MD, 1977, pp 421–478.

Heckenlively JR . Clinical findings in retinitis pigmentosa. In: Heckenlively JR (ed). Retinitis Pigmentosa. B Lippincott Company: London, 1998, pp 68–89.

Leber T . Ueber retinitis pigmentos and angeborene amaurose. Albrercht von Graeefes Arch Ophthalmol 1869; 15: 1–25.

Koenekoop RK . An overview of Leber congenital amaurosis: a model to understand human retinal development. Survery Ophthalmol 2004; 49 (4): 379–398.

Kaplan J . Leber congenital amaurosis: from darkness to spotlight. Ophthalmic Genet 2008; 29: 92–98.

Jalili IK . Cone-rod congenital amaurosis associated with congenital hypertrichosis: an autosomal recessive condition. J Med Genet 1989; 26 (8): 504–510.

Inglehearn CF . Molecular genetics of human retinal dystrophies. Eye (Lond) 1998; 12 (Part 3b): 571–579.

Wissinger B, Gamer D, Jagle H, Giorda R, Marx T, Mayer S et al CNGA3 mutations in hereditary cone photoreceptor disorders. Am J Hum Genet 2001; 69 (4): 722–737.

Parry DA, Mighell AJ, El-Sayed W, Shore RC, Jalili IK, Dollfus H et al Mutations in CNNM4 cause Jalili syndrome, autosomal recessive cone-rod dystrophy and amelogenesis imperfecta. Am J Hum Genet 2009; 84 (2): 266–273.

Polok B, Escher P, Ambresin A, Chouery E, Bolay S, Meunier I et al Mutations in CNNM4 cause recessive cone-rod dystrophy with amelogenesis imperfecta. Am J Hum Genet 2009; 84 (2): 259–265.

Kjaer KW, Hansen L, Schwabe GC, Marques-de-Faria AP, Eiberg H, Mundlos S et al Distinct CDH3 mutations cause ectodermal dysplasia, ectrodactyly, macular dystrophy (EEM syndrome). J Med Genet 2005; 42 (4): 292–298.

Sprecher E, Bergman R, Richard G, Lurie R, Shalev S, Petronius D et al Hypotrichosis with juvenile macular degeneration caused by mutation in CDH3, encoding P-cadherin. Nat Genet 2001; 29 (2): 134–136.

Indelman M, Hamel CP, Bergman R, Nischal KK, Thompson D, Surget MO et al Phenotypic diversity and mutation spectrum in hypotrichosis with juvenile macular dystrophy. J Invest Dermatol 2003; 121 (5): 1217–1220.

Samra D, Abraham FA, Treister G . Inherited progressive cone-rod dystrophy and alopecia. Metab Pediatr Syst Ophthalmol 1988; 11 (1–2): 83–85.

Gershoni-Baruch R, Leibo R . Aplasia cutis congenital, high myopia, and cone-rod dysfunction in two sibs: a new autosomal recessive disorder. Am J Med Genet 1996; 61 (1): 42–44.

Walters BA, Raff ML, Hoeve JV, Tesser R, Langer LO, France TD et al Spondylometaphyseal dysplasia with cone rod dystrophy. Am J Med Genet 2004; 129 (3): 265–276.

Sousa SB, Russell-Eggitt I, Hall C, Hall BD, Hennekam RC . Further delineation of spondylometaphyseal dysplasia with cone-rod dystrophy. Am J Med Genet 2008; 146A (124): 3186–3194.

Ausems MG, Wittebol-Post D, Hennekam RC . Cleft lip and cone-rod dystrophy in a consanguineous sibship. Clin Dysmorphol 1996; 5 (4): 307–311.

Meire FM, Van Genderen MM, Lemmens K, Ens-Dokkum MH . Thiamine-responsive megaloblastic anemia syndrome (TRMA) with cone-rod dystrophy. Ophthalmic Genet 2000; 21 (4): 243–250.

Harville HM, Held S, Diaz-Font A, Davis EE, Diplas BH, Lewis RA et al Identification of 11 novel mutations in 8 BBS genes by high-resolution homozygosity mapping. J Med Genet 2010; 47 (4): 262–267.

Russell-Eggitt IM, Clayton PT, Coffey R, Kriss A, Taylor DS, Taylor JF . Alström syndrome: report of 22 cases and literature review. Ophthalmology 1998; 105: 1274–1280.

Aleman TS, Cideciyan AV, Volpe NJ, Stevanin G, Brice A, Jacobson SG . Spinocerebellar ataxia type 7 (SCA7) shows a cone-rod dystrophy phenotype. Exp Eye Res 2002; 74 (6): 737–745.

Michalik A, Martin JJ, Van Broeckhoven C . Spinocerebellar ataxia type 7 associated with pigmentary retinal dystrophy. Eur J Hum Genet 2004; 12 (1): 2–15.

Aldred MJ, Savarirayan R, Crawford PJM . Amelogenesis imperfecta: a classification and catalogue for the 21st Century. Oral Dis 2003; 9 (1): 19–23.

Soames JV, Southam JC . Disorders of the development of the teeth and craniofacial anomalies. In: Soames JV, Southam JC (eds). Oral Pathology. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2005, pp 3–17.

Crawford PJM, Aldred M, Bloch-Zupan A . Amelogenesis imperfecta. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2007; 2: 17.

Mégarbané A, Ghanem I, Waked N, Dagher F . A newly recognized autosomal recessive syndrome with short stature and oculo-skeletal involvement. Am J Med Genet 2006; 140 (14): 1491–1496.

Thodén CJ, Ryöppy S, Kuitunen P . Oculodentodigital dysplasia syndrome: report of four cases. Acta Paediatr Scand 1977; 66 (5): 635–638.

Atasu M, Eryilmaz A, Genc A, Ozcan M, Ozbayrak S . Congenital hypodontia of maxillary lateral incisors in association with coloboma of the iris and hypomaturation type of amelogenesis imperfecta in a large kindred. J Clin Pediatr Dent 1997; 21 (4): 341–355.

Chaabouni H, M'Rad R, Younsi CF, Ferchiou A . Association of Recklinghausen's disease, dental dystrophy and myopia in a Tunisian family. J Genet Hum 1988; 36 (3): 173–176.

Inan UU, Yilmaz MD, Demir Y, Degirmenci B, Ermis SS, Ozturk F . Characteristics of lacrimo-auriculo-dento-digital (LADD) syndrome: case report of a family and literature review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2006; 70 (7): 1307–1314.

Jalili IK, Smith NJ . A progressive cone-rod dystrophy and amelogenesis imperfecta: a new syndrome. J Med Genet 1988; 25 (11): 738–740.

Downey LM, Keen TJ, Jalili IK, McHale J, Aldred MJ, Robertson SP et al Identification of a locus on chromosome 2q11 at which recessive amelogenesis imperfecta and cone-rod dystrophy cosegregate. Eur J Hum Genet 2002; 10 (12): 865–869.

Michaelides M, Bloch-Zupan A, Holder GE, Hunt DM, Moore AT . An autosomal recessive cone–rod dystrophy associated with amelogenesis imperfecta. J Med Genet 2004; 41 (6): 468–473.

Arden GB, Barrada A, Kelsey JH . New clinical test of retinal function based upon the standing potential of the eye. Br J Ophthalmol 1962; 46 (8): 449–467.

Bellamy RJ, Inglehearn CF, Jalili IK, Jeffreys AJ, Bhattacharya SS . Increased band sharing in DNA fingerprints of an inbred human population. Human Genet 1991; 87 (3): 341–347.

Bäckman B, Holm AK . Amelogenesis imperfecta: prevalence and incidence in a northern Swedish county. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1986; 14 (1): 43–47.

Sundell S . Hereditray amelogenesis imperfecta, genetic and clinical study in a Swedish child population. Swed Dent J suppl 1986; 31: 1–38.

François A, De Rouck A, Verriest G, De Laey JJ, Cambie E . Progressive generalized cone dysfunction. Ophthalmologica 1974; 169 (4): 255–284.

Schornack MM, Brown WL, Siemsen DW . The use of tinted contact lenses in the management of achromatopsia. Optometry 2007; 78 (7): 328.

Iqbal M, Jalili IK . Congenital onset central chorioretinal dystrophy associated with high myopia. Eye (Lond) 1998; 12 (Pt 2): 260–265.

Cartwright AR, Kula K, Wright TJ . Craniofacial features associated with amelogenesis imperfecta. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol 1999; 19 (3): 148–156.

Rowley R, Hill FJ, Winter GB . An investigation of the association between anterior open-bite and amelogenesis imperfect. Am J Orthod 1982; 81 (3): 229–235.

Chowers I, Liu D, Farkas RH, Gunatilaka TL, Hackam AS, Bernstein SL et al Gene expression variation in the adult human retina. Hum Mol Genet 2003; 12 (22): 2881–2893.

Enard W, Khaitovich P, Klose J, Zöllner S, Heissig F, Giavalisco P et al Intra- and interspecific variation in primate gene expression patterns. Science 2002; 296 (5566): 340–343.

Khanna H, Davis EE, Murga-Zamalloa CA, Estrada A, Lopez I, den Hollander AI et al A common allele in RPGRIP1L is a modifier of retinal degeneration. Nat Genet 2009; 41 (6): 739–745.

Shomar B, Müller G, Yahya A, Askar S, Sansur R . Fluorides in groundwater, soil and infused black tea and the occurrence of dental fluorosis among school children of the Gaza strip. J Water Health 2004; 2 (1): 23–35.

Shailaja K, Johnson ME . Fluorides in groundwater and its impact on health. J Environ Biol 2007; 28 (2): 331–332.

Fewtrell L, Smith S, Kay D, Bartram J . An attempt to estimate the global burden of disease due to fluoride in drinking water. J Water Health 2006; 4 (4): 533–542.

Lu Y, Sun ZR, Wu LN, Wang X, Lu W, Liub SS . Effects of high-fluoride water on intelligence in children. Fluoride 2000; 33: 74–78.

Crespi CL, Seixas GM, Turner T, Penman BW . Sodium fluoride is a less efficient human cell mutagen at low concentrations. Mol Mutagen 1990; 15 (2): 71–77.

Amini M, Mueller K, Abbaspour K, Rosenberg T, Afyuni M, Møller K et al Statistical modeling of global geogenic fluoride contamination in groundwaters. Environ Sci Technol 2008; 42 (10): 3483–3484.

Dawson DV, Xiao X, Levy SM, Santiago-Parton S, Warren JJ, Broffitt B et al Candidate gene associations with fluorosis in the early permanent dentition. J Dent Res 2008; 87B: 0009. (www.dentalresearch.org).

Choubisa SL, Choubisa L, Sompura K, Choubisa D . Fluorosis in subjects belonging to different ethnic groups of Rajasthan, India. J Commun Dis 2007; 39 (3): 171–177.

Green SG, Bear JC, Johnson GJ . The burden of genetically determined eye disease. Br J Ophthalmol 1986; 70 (9): 696–699.

Acknowledgements

The author is indebted to the support of: St John's Ophthalmic Hospital Outreach team, St John's Ophthalmic Hospital, Jerusalem and the Order of St John in the UK in providing the support and funding for the blind school survey and the assessment of affected families from 1985 to 1987, and the enormous support and encouragement of the late Sir Stephen Miller, the then Hospitaller. The author also thanks the late Professor NJ Smith, then professor of dental radiology at Kings College Dental School London, for carrying out the dental examination and establishing the dental diagnosis and Judith Alexander, Orthoptist at St John's Ophthalmic Hospital, for carrying out orthoptic examinations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Eye website

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jalili, I. Cone-rod dystrophy and amelogenesis imperfecta (Jalili syndrome): phenotypes and environs. Eye 24, 1659–1668 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2010.103

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2010.103

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Identification of a mutation in CNNM4 by whole exome sequencing in an Amish family and functional link between CNNM4 and IQCB1

Molecular Genetics and Genomics (2018)

-

A novel mutation and variable phenotypic expression in a large consanguineous pedigree with Jalili syndrome

Eye (2016)

-

Intra-familial phenotype variability in patients with Jalili syndrome

Eye (2015)