Abstract

Purpose

To determine the current management of acquired nystagmus by ophthalmologists and neurologists.

Methods

Questionnaires were sent to ophthalmologists (850) and neurologists (434) in the United Kingdom. Estimated numbers of patients seen with acquired nystagmus, treatment options used, and the results of treatment of the patients were collected.

Results

Response rate was 37% for ophthalmologists and 34% for neurologists. The most common causes of acquired nystagmus were estimated to be multiple sclerosis and stroke. 58% of ophthalmologists and 94.5% of neurologists reported seeing patients with nystagmus. The most commonly used medical treatment was gabapentin and baclofen. Other drugs used were clonazepam, carbamazepine, benzhexol, ondansetrone, buspirone, memantine, and botulinum toxin (n=3). Eleven ophthalmologists and 52 neurologists noted symptomatic improvement with medical treatment. Eleven ophthalmologists and 44 neurologists noted improvement in visual acuity (VA). Occurrence of side effects noted with baclofen and gabapentin treatments were similar.

Conclusion

A variety of drugs are used to treat acquired nystagmus in the UK. Baclofen and gabapentin are the drugs most commonly used and are reported to cause significant improvement in symptoms and VA. Better knowledge of the action of drugs in nystagmus is needed to establish guidelines and to give patients wider access to treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nystagmus is an involuntary to and fro movement of the eyes that can cause decrease in visual acuity (VA) and motion perception. Acquired nystagmus causes perception of constant motion of the environment called oscillopsia.

The causes of acquired nystagmus include several neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis, stroke, tumours, trauma, vestibular imbalance, medications, or toxins.

A number of drugs have been reported to improve nystagmus. Cholinergic agents scopolamine and benztropine suppress nystagmus when given intravenously,1 but orally administered trihexyphenidyl had little effect.2 Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) has been shown in animal experiments to be involved in gaze holding.3 There is evidence to suggest that drugs with GABAergic activity decrease nystagmus. Baclofen,4 clonazepam,5 and valproate6 have been reported to help some patients. In a double-masked study, Averbuch-Heller et al7 have shown that gabapentin is clearly more effective than baclofen in 21 patients with acquired nystagmus owing to multiple sclerosis and stroke. They suggested that gabapentin may be useful in acquired pendular nystagmus, but only occasional patients of downbeat nystagmus are benefited by gabapentin. They concluded that GABAergic drugs are effective for the treatment of acquired nystagmus, although their exact mechanism of action is not fully understood.8 We described a patient with acquired nystagmus owing to multiple sclerosis who benefited from combined treatment with gabapentin and surgery (vertical Kestenbaum procedure), in whom gabapentin reduced the horizontal nystagmus but not the vertical nystagmus.9 We have shown gabapentin and memantine to be effective in acquired and congenital nystagmus.10 Bandini et al11 showed that gabapentin is more effective to reduce acquired nystagmus than vigabatrin, a purely GABAergic medication. As gabapentin has also glutaminergic action, the authors postulated that it is mainly the glutamine antagonistic action of gabapentin that is responsible for reducing the nystagmus. Sympathomimetics, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors are the other pharmacologic modalities, which have been used in the treatment of acquired nystagmus.12 Strupp et al13 has shown that single doses of 3,4-diaminopyridine significantly improved down beat nystagmus. Injection of retrobulbar botulinum toxin either into extraocular muscles or retrobulbar space is another approach for the treatment of nystagmus.14, 15 However, they often cause side effects such as diplopia or ptosis.

The purpose of this study was to determine the current management options used by ophthalmologists and neurologists in the United Kingdom in patients with acquired nystagmus. We aimed to find out why a proportion of patients are not offered treatment.

Materials and methods

An anonymous questionnaire was sent out to 850 consultant ophthalmologists and 434 consultant neurologists in the United Kingdom. Names were obtained from the Royal College of Ophthalmologists and the Royal College of Physicians, the Association of British Neurologists.

The questionnaire included questions about speciality and subspeciality of the consultant, number of patients with acquired nystagmus seen per year, with estimated percentages for possible aetiologies like multiple sclerosis, stroke, and traumatic or vestibular causes. The preferred referral route was enquired about as well. The consultants were asked about drugs of their preference and estimated percentages of patients showing symptomatic improvement, improved VA, and experienced side effects. Finally, they were asked whether they carried out any surgical correction of nystagmus.

Results

Questionnaires of 312 (36.7%) ophthalmologists and 148 (34%) neurologists were returned.

One hundred and eighty-one (58%) ophthalmologists reported seeing patients with acquired nystagmus in clinics as compared to 140 (94.5%) neurologists.

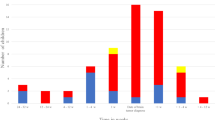

Of the 181 ophthalmologists seeing patients with acquired nystagmus in clinics, 154 (85%) saw less than five patients annually, 28 (15.5%) saw more than five patients, and three (1.65%) saw more than 20 patients annually. Of the 140 neurologists seeing patients with acquired nystagmus in clinics, 22 (15.7%) saw less than five patients annually, whereas 117 (83.5%) saw more than five patients. Fifty-one (30%) neurologists saw more than 20 patients a year.

Forty-four ophthalmologists and 82 neurologists mentioned MS as the cause of nystagmus in more than 50% of patients, whereas stroke was a cause of nystagmus in more than 50% of patients seen by 15 ophthalmologists and four neurologists. Tumours were the cause of nystagmus in more than 50% of patients seen by seven ophthalmologists, whereas vestibular pathology was the cause of nystagmus in more than 50% of patients seen by four ophthalmologists and four neurologists (see Table 1)

Most ophthalmologists referred patients to neurologists or neuro-ophthalmolgists, whereas most neurologists managed patients with acquired nystagmus themselves (see Table 2). Only 10 (3.2%) ophthalmologists indicated that they treat these patients medically, whereas 300 (96%) would not treat them medically. Most of the ophthalmologists who medically treat patients of nystagmus have identified neuro-ophthalmology or ocular motility as their area of special interest. Eleven (3.5%) ophthalmologists treated nystagmus surgically. In contrast, 87 (58.7%) neurologists indicated that they treat acquired nystagmus medically and 56 (37.8%) neurologists do not treat them medically. (The above percentages do not add up to 100%, as a few questionnaires had incomplete responses.)

Baclofen and gabapentin are the most commonly used drugs by neurologists and ophthalmologists (see Table 3). Gabapentin was estimated to be slightly more effective than baclofen for symptomatic improvement as well as increase of VA (see Table 4a). The frequency of side effects of these two drugs was estimated to be approximately similar (Table 4b).

Four ophthalmologists have carried out Kestenbaum or modified Kestenbaum procedures. Three ophthalmologists used botulinum toxic either in isolation or with squint surgery. One mentioned four-muscle recession.

Discussion

In our survey, we had approximately equal rates of response from ophthalmologists (36.7%) and neurologists (34%). As only one-third of ophthalmologist and neurologist returned the questionnaire, the results need to be interpreted with some caution. Fewer ophthalmologists (3.2%) are currently treating patients with acquired nystagmus than neurologists (60.8%), but ophthalmologists tend to refer more frequently to neuro-ophthalmologists or neurologists.

The most common causes of acquired nystagmus were estimated to be multiple sclerosis and stroke. Tumours and vestibular causes were less common.

Baclofen and gabapentin were the drugs most commonly used for the treatment of acquired nystagmus and were reported to cause significant symptomatic and visual improvement. However, the medical treatment of nystagmus is variable and several other drugs were reported to be used. There also appears to be a variation in the rate in which the patients are given pharmacological treatment. In our own experience, gabapentin and memantine have not caused any major side effects even when used in high dosage. The main side effects were tiredness, which occurred usually in patients with neurological disorders. However, this was in all patients, accepted by patients for the benefit of having less oscillopsia. Relative unfamiliarity of the various drugs among general ophthalmologists might explain reticence in offering medical treatment. The need of subspecialist care and luck of evidence bases in treatment and large placebo-controlled studies may reduce the access of patients for the treatment of nystagmus.

Rigorous studies comparing the effect of drugs improving acquired nystagmus are rare. Only two double-masked controlled trials2, 11 have been performed. Currently, the management of acquired nystagmus is largely empirical. Randomised controlled studies are needed to establish treatment guidelines. They would help neurologists and ophthalmologists to decide on treatment modalities and possibly give patients wider access to treatment.

References

Barton JJS, Huaman AG, Sharpe JA . Muscarinic antagonists in the treatment of acquired pendular and downbeat nystagmus. A double blinded trial of three intravenous drugs. Am Neurol 1994; 35: 319–325.

Leigh RJ, Burnstine TH, Ruff RL, Kasmer RJ . The effect of anticholinergic drugs on upbeat and downbeat nystagmus. A double-blind study of trihexyphenidyl and trihexethyl chloride. Neurology 1991; 41: 1737–1741.

Arnold DB . Nystagmus induced by pharmacological inactivation of the brainstem ocular motor integrator in monkeys. Vision Res 1999; 39: 4286–4295.

Dieterich M, Straube A, Brandt TH, Paulus W, Buttner U . The effects of baclofen and cholinergic drugs on upbeat and downbeat nystagmus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1991; 54: 627–632.

Currie JN, Matsuo V . The use of clonazepam in treatment of nystagmus-induced oscillopsia. Ophthalmology 1986; 93: 924–932.

Lefkowitz D, Harpold G . Treatment of ocular myoclonus with valproic acid. Ann Neurol 1985; 17: 103–104.

Avebuch-Helleer L, Tusa RJ, Fuhry L, Rottach KG, Ganser GL, Heide W et al. A double blind controlled study of gabapentin and baclofen as treatment of acquired nystagmus. Ann Neurol 1997; 41: 818–825.

Taylor CP . Emerging perspectives on the mechanism of action of gabapentin. Neurology 1994; 44 (Suppl 5): s10–s16.

Jain S, Proudlock F, Constantinescu C, Gottlob I . Combined pharmacologic and surgical approach to acquired nystagmus due to multiple sclerosis. Am J Ophthalmol 2002; 134: 780–782.

Shery T, Proudlock FA, Sarvananthan N, McLean RJ, Gottlob I . The effects of gabapentin and memantine in acquired and congenital nystagmus—a retrospective study. Br J Ophthalmol 2006 [E-pub ahead of print].

Bandini E, Castello E, Mazzacca L, Mancardi GL, Solaro C . Gabapentin but not vigabatrin is effective in the treatment of acquired nystagmus in multiple sclerosis: how valid is the GABAergic hypothesis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001; 71 (1): 107–110.

Ronald J . Tusa. Semin Ophthalmol 1999; 14 (2): 65–73.

Strupp M, Schuler O, Krafczyk S, Jahn K, Schautzer F, Buttner U et al. Treatment of downbeat nystagmus with 3,4-diaminopyridine: a placebo-controlled study. Neurology 2003; 61 (2): 158–159.

Ruben ST, Lee JP, O’Neill DO, Dunlop I, Elston JS . The use of botulinum toxin for treatment of acquired nystagmus and oscillopsia. Ophthalmology 1994; 101: 783–787.

Repka MX, Savino PJ, Reinecke RD . Treatment of acquired nystagmus with botulinum neurotoxin. Arch Ophthalmol 1994; 112: 1320–1324.

Acknowledgements

We thank all Consultant Neurologists and Ophthalmologists who returned the questionnaire. We are grateful to The Association of British Neurologists who provided a list of their members. Medisearch, Leicester, supported this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The Corresponding author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive license (or nonexclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in BJO and any other BMJPGL products and sublicenses such use and exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our license

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Choudhuri, I., Sarvananthan, N. & Gottlob, I. Survey of management of acquired nystagmus in the United Kingdom. Eye 21, 1194–1197 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702434

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702434