Abstract

Purpose To describe the presentation of cytomegalovirus retinitis (CMVR) in a series of infants.

Methods Immunocompromised infants with either HIV or systemic cytomegalovirus (CMV) were examined for CMVR. Ocular involvement was recorded and monitored by digital imaging.

Results Five infants were detected to have CMVR. All the infants demonstrated changes within the macula. One infant progressed from a fine granular pattern to fulminant CMVR.

Conclusion Infants under a year with CMVR have a predilection for the disease to present at the macula, in contrast to the presentation in adults, which tends to involve more peripheral parts of the retina.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the most frequent intrauterine viral infection affecting between 0.5% and 2.0% of all live births,1 and evidence of ocular involvement is present in 5–30%2 of infants exhibiting general symptoms and signs of the infection. CMV retinitis (CMVR) is the most common opportunistic infection affecting the eyes in adults with HIV and before combination therapy, studies showed that between 20 and 40%2,3 were affected. In contrast, CMVR has been reported in only 5% of children with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).2,4

In adults, CMVR presents in the peripheral retina in 85% of instances.2 It may affect one or both eyes and is frequently multifocal. It is typically recognised by a ‘fulminant’ picture of retinal vasculitis and vascular sheathing with areas of yellow-white, full-thickness, retinal necrosis producing retinal oedema associated with haemorrhage and hard exudates. The ‘indolent or granular’ variant describes a pattern in which there is less oedema and no haemorrhage or vascular sheathing, and this variant is seen more often in the periphery of the retina. These fulminant and indolent forms represent two ends of the clinical spectrum, and an individual may exhibit elements of both. Isolated macular involvement occurs in less than 5% of eyes in adults.3

On the clinical suspicion that CMVR might present differently in infants and adults, we analysed the ocular findings of a series of immunocompromised infants.

Methods

Immunocompromised infants presenting to St Mary's Hospital Paediatric Infectious Diseases Unit, London, between September 1999 and October 2001, with either HIV or under investigation for systemic CMV disease, were screened for CMVR by retinal examination. Contact digital photography was performed in infants with retinal changes using the RetCam 120 wide-field digital fundus camera (Massie Labs, Dublin, CA, USA). CMV infection was confirmed through virus shedding in the urine and the presence of CMV viraemia. CMV viral load was measured using assays on either whole blood or plasma and were fully quantitative looking at nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR), second round on the light cycler real time detection using syber green dye (Micropathology Ltd, Coventry, UK).

Where intravitreal ganciclovir was administered, a vitreous biopsy was taken and qualitative PCR-based assays confirmed the presence of CMV DNA. In the HIV-affected infants, the viral load was measured using the Chiron bDNA assay.

Results

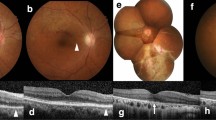

Retinal abnormalities were detected in five infants screened (age 0–10 months), four had the HIV infection and one had congenital CMV infection (Table 1). There were two male and three female infants. All of them had bilateral disease. The clinical presentation varied from subtle white flecks at the macula, giving a granular appearance with central pigment epithelial disturbance (Figures 1a and b). The clinical findings did not progress over 3 months in these two infants. One infant displayed a similar subtle granular appearance at presentation, but this progressed to florid CMVR over 10 days (Figure 1c). The remaining two infants demonstrated more florid disease at presentation, more characteristic of typical CMVR (Figures 1d and e). The presentation was located at the macula in all the infants in at least one eye.

Colour photographs of infants with CMV retinitis: (a) Infant 1: Right and left fundal photographs. Shows subtle white flecks at the macula, giving a granular appearance with central pigment epithelial disturbance. (b) Infant 2: Right and left fundal photographs. Shows subtle flecks at the macula in the left eye and a larger noncentral lesion in the right fundus. Neither changed in clinical appearance. (c) Infant 3: Right and left fundal photographs. Shows a subtle granular appearance at presentation, which progressed to florid CMVR over 10 days. (d) Infant 4: Right and left fundal photographs. As presented with a florid picture of CMVR. (e) Infant 5: Right and left fundal photographs. Presented with florid CMVR.

Three infants with active retinitis had vitreous samples taken, which confirmed the presence of CMV DNA. They were treated with intravenous ganciclovir with or without foscarnet and subsequently with serial intraocular injections of ganciclovir.

Discussion

CMVR is a significant cause of ocular morbidity in immunocompromised patients and here we show that the pattern of presentation, both with respect to its location within the retina and its progression, may be different in infants compared to adults.

Several reasons for differences in the presentation of CMVR have been postulated. For example, reactivation of latent infections is less likely to be present in children, which makes the infection more likely to be a primary infection.2 The immaturity of the immune system in infants is likely to make the response to infection more severe.5 Finally, different exposure to the virus through breast milk in the perinatal period as opposed to sexual or percutaneous transmission may affect the presentation.6

The HIV-infected infants in our series were all immunosuppressed and were in their primary HIV viraemic phase, in contrast to adults with CMVR, who present later in the course of their illness (when the HIV disease progresses to severe immunosuppression).

Moreover, as CMV and HIV infections occur during an important immunological developmental period, there may be interactions between the infections.7

The above factors may contribute to the differences in disease expression, for example, in a series of infants described by Baumal et al4 89% of paediatric cases presented bilaterally (in contrast to approximately 33% of adults) and the retinitis was noted to have a predisposition for posterior pole of the eyes in infants as compared to adults.4 Similar features of CMVR having a predisposition for the posterior pole and presenting bilaterally have been recorded in other series of infants with HIV or with congenital CMV. The distribution of active retinitis in infants in other series is shown in Table 2.

Congenital CMV infections do not present in the typical haemorrhagic manner, as seen in immunocompromised children,1 which we noted in the infant with congenitally acquired CMV. No identifiable factors were associated with the lack of progression in the infants with stable retinitis over the study period.

Our findings are interesting, but have limitations. Although the number of infants in this series is small, they were systematically examined. It was not a prospective study, rather the response to a clinical suspicion, and represents in effect a pilot study that may stimulate further investigation.

References

Coats DK, Demmler GJ, Paysee EA, Du LT, Libby C . Ophthalmologic findings in children with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. J AAPOS 2000; 4(2): 110–116.

Cunningham ET, Pepose JS, Holland GN . Cytomegalovirus infections of the retina. In: Ryan SJ (ed). Retina, 3rd ed. Mosby: London, 2001, pp 1558–1575.

Studies of Ocular Complications of AIDS (SOCA) Research Group in Collaboration with the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG). Foscarnet–ganciclovir cytomegalovirus trial. 5. Clinical features of cytomegalovirus retinitis at diagnosis. Am J Ophthalmol 1997; 124: 141–157.

Baumal CR, Levin AV, Read SE . Cytomegalovirus Retinitis in Immunosuppressed children. Am J Ophthalmol 1999; 127(5): 550–558.

Williams AJ, Duong T, McNally LM, Tookey PA, Masters J, Miller R et al. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and cytomegalovirus infection in children with vertically acquired HIV infection. AIDS 2001; 15(3): 335–339.

Du LT, Coats DK, Kline MW, Rosenblatt HM, Bohannon B, Contant CF et al. Incidence of presumed cytomegalovirus retinitis in HIV-infected paediatric patients. J AAPOS 1999; 3(4): 245–249.

Levin AV, Zeichner S, Duker JS, Starr SE, Augsburger JJ, Kronwith S . Cytomegalovirus retinitis in an infant with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Pediatrics 1989; 84: 683–687.

Pass RF, Stagno S, Myers GJ, Alford CA . Outcome of symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection: results of long-term longitudinal follow up. Paediatrics 1980; 66: 758–762.

Yamanaka H, Yamanaka J, Okazaki KI, Miyazawa H, Kuratsuji T, Genka I et al. Cytomegalovirus Infection of Newborns Infected with HIV-1 from Mother: Case report. Jpn J Infect Dis 2000; 53: 215–216.

Vadala P, Fortunato M, Capozzi P, Vadala F . Case report: CMV retinitis in two 10-month-old children with AIDS. J Paediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1998; 35: 334–335.

Dennehy PJ, Warman R, Flynn JT, Scott GB, Mastrucci MT . Ocular manifestations in paediatric patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 1989; 107: 978–982.

Salvador F, Blanco R, Colin A, Galan A, Gil-Gibernau JJ . Cytomegalovirus retinitis in paediatric acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: report of two cases. J Paediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1993; 30: 159–162.

Hammond CJ, Evans JA, Shah SM, Acheson JF, Walters MDS . The spectrum of eye diseases in children with AIDS due to vertically transmitted HIV disease: clinical findings, virology and recommendations for surveillance. Graefe's Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1997; 235: 125–129.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wren, S., Fielder, A., Bethell, D. et al. Cytomegalovirus Retinitis in infancy. Eye 18, 389–392 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700696

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700696