Abstract

Purpose To report the type and severity of ocular and orbital injuries caused by rubber bullets.

Methods A total of 42 consecutive patients seen over a 3-month period with ocular and orbital rubber bullet injuries were assessed clinically and radiographically within 1 day of injury, and the findings were recorded. Clinical outcomes following treatment were also recorded up to 6 months postinjury.

Results A total of 90% of the patients were male. The mean age of patients was 25.0 years (4–60). Of the patients, 54% had lid or skin lacerations, 40% hyphaema, 38% ruptured globe, 33% orbital fracture, 26% retinal damage, and 21% retained rubber bullet in or around the orbit. At follow-up, 53% of the patients had a visual acuity of less than 6/60, 7% less than 6/18 to 6/60, and 40% 6/18 or better.

Conclusions The term ‘rubber bullet’ is misleading. ‘Rubber bullets’ cause a wide variety of ocular and periocular injuries. Orbital fractures are common. The tissues of the orbit are easily penetrated. If the globe is hit, it is rarely salvageable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The upsurge of civil unrest in the Palestinian territories that started on 29 September 2000, known as the Second Intifada, has brought with it a large number of injuries. St John Eye Hospital in Jerusalem, one of only a few eye departments catering for the West Bank population and by far the largest, has seen many of the eye injuries. A large percentage of these injuries have been caused by rubber bullets.

Patients and methods

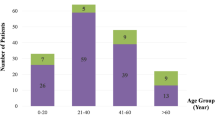

The case notes of 42 consecutive patients who attended the hospital between 29 September and 22 December 2001 with a history of rubber bullet injury were retrieved and data collected retrospectively. X-rays and CT scans, where taken, were reviewed and reports obtained. Particular note was made of the type and severity of injury and any surgery performed. Follow-up data were recorded on all patients up to 6 months postinjury. Of the patients, 38 (90%) were males and four (10%) females. The age range was from 4 to 60 years, mean 25.0.

Results

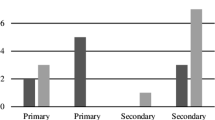

The incidence of different types of injury found are listed in Table 1.

In all, 24 patients underwent surgery immediately after presentation. Nine patients required further surgery within the first 6 months. All procedures are listed in Table 2. One patient who underwent repair of a ruptured globe developed sympathetic ophthalmia in the other eye.

The visual outcome of affected eyes (best corrected acuity) is recorded in Table 3.

Discussion

‘Nonlive’ rounds have been and are used by police forces and armies in various countries round the world as a means to break up civil disturbances.1,2,3 Among these are a variety of very different projectiles described as ‘rubber’ or ‘plastic’ bullets. These terms can be misleading, as most consist of a metallic core surrounded by a coating of rubber or plastic. The ‘rubber bullet’ introduced by the British Army in Northern Ireland in 1970 was more like a rubber baton, being 15 cm in length and around 140 g.1 For safety reasons, these bullets were replaced with plastic bullets 1975, but whether these were actually any safer is uncertain.4,5 The same rubber and plastic bullets were used in South Africa in the 1980s.2 The Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) have more than one type of rubber bullet. The most commonly used type (Figure 1) and the one that we believe injured all our patients is a cylindrical rubber-coated metal bullet approximately 1.7 cm in diameter and length with a mass of 15.4 g.3 Known as the improved rubber bullet (IRB), it was introduced in 1989 to replace the standard rubber bullet (SRB), which is still used occasionally. The SRB comprises a 2-cm-diameter steel sphere coated thinly in rubber, weighing 14 g. The IRB is considered to be more accurate, and therefore less likely to cause unintended injuries.

The expressed purpose for the use of rubber and plastic bullets by the IDF is as ‘a nonlethal means to disperse demonstrations’ when other lesser means have been tried and failed.6 Recommendations for their use in other parts of the world are similar. The intention should be to inflict the minimum injury necessary to control the target population. Inevitably casualties occur, including fatalities, and their use regularly comes under attack, particularly from human rights groups.5,6,7,8 As a result of their potential to cause severe injury if used indiscriminately, the IDF issues regulations to restrict their use. These include a minimum firing distance of 40 m, not firing at children, only firing at the legs of a person who has been identified as a rioter or stone thrower, not using rubber bullets at night unless visibility is good, and making an assessment of whether their use is ‘proper’ each time they are used.9 These regulations depend on the ability of individual soldiers to judge distances and lighting levels accurately, and to gauge the danger level of a civil disturbance. Understandably, such abilities may be flawed. The Israeli human rights group B'Tselem6 states, ‘Estimating distance is not an easy task under normal circumstances, much less under the pressure of a stormy demonstration. In such situations the security forces and demonstrators move, and the distance between them changes. A shooter's mistake in judging distance is liable to result in death.'

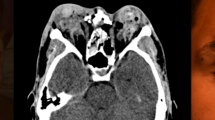

The type of injury caused by a projectile will depend on many factors, including its mass, size, shape and velocity on impact, as well as the nature of the tissues it hits. The ‘rubber bullets’ that we believe injured all our patients are flat-ended rubber-coated metal cylinders (IRBs). All nine bullets that we retrieved from the orbits of our patients were of this type, and no other types of bullets were brought in by witnesses or any of the patients in our series. Round-ended bullets travelling at high velocity cause penetrating injuries. Flat-ended bullets are more likely to cause blunt injuries, especially if travelling slowly. However, if travelling fast enough, even flat-ended bullets will penetrate tissues including muscle and bone.4

The muzzle velocity of the bullets used against our patients is 100 m/s and the official safe firing distance is over 40 m.9 Hiss et al3 consider this distance too small, estimating the safe distance to be at least 50 m. As a result of their poor aerodynamic shape, the bullets lose velocity rapidly and kinetic energy even more rapidly (proportional to mass and square of the velocity). Hence the range wherein they are safe, yet still effective, is quite small. When fired from less than the safe distance, the energy of a bullet can be several times more than at the safe distance and easily sufficient to penetrate soft tissues.10 We retrieved rubber bullets in or around the orbits of nine (21%) of our patients (Figures 2 and 3). Frequently, these cases had orbital fractures and in two cases the bullet had penetrated to a paranasal sinus via the orbit (one in the ethmoid sinus and one in the maxillary sinus). Four patients with orbital fractures went on to orbital reconstruction as secondary procedures. We have seen a patient (not in this series) who had a rubber bullet removed from the sella tursica in another hospital prior to presenting to us with a blind ruptured eye.

In a blunt injury, the energy of a projectile is entirely transmitted on impact. In a penetrating injury, as the projectile passes through tissues, it also transmits energy in a direction perpendicular to its path and this is greater if the projectile is blunt rather than sharp. The degree of collateral tissue damage seen as contusion and haemorrhage in our patients bears this out. This, rather than direct contact of bullet and bone, may be the cause of some of the many orbital fractures seen in our patients.

In our series, more males were affected than females as is usual in trauma studies, and the mean age was 25 years. However, such a high proportion (90%) of males presumably reflects the make-up of those involved in riot situations in the occupied territories. When Jaouni and O'Shea11 looked at eye injuries from the First Intifada, they found that a similar proportion (84.7%) were males but the mean age of their cases was only 17 years. Of our cases, 24% were children below the age of 18 years. Although this is less than what Jaouni and O'Shea found, it is still worryingly high and maybe explained by the fact that so many Intifada disturbances occur in residential areas. Given these facts, it may be that, although all population subgroups are vulnerable initially, the women and girls withdraw from a disturbance while the men and boys stay around, sustaining more injuries. The practice of throwing stones starts early among Palestinians and accounts for significant numbers of ‘accidental’ penetrating ocular injuries in children. In a 2-year study of penetrating eye injuries in Palestinian children, Elder12 estimates the national incidence of such injuries at 2% which is high compared with other countries. In his study, carried out at a more peaceful time, 14% of the injuries were attributable to the military occupation and most others were the result of dangerous play. None was caused by toys or in the practice of organised sport. It should also be noted that the Palestinians are a nation of young adults and children. Of the population, 57% is below the age of 20 years and 47% is below the age of 15years.13 In the UK these figures are 25 and 19%, respectively.14

Over half (53%) of our patients were left with visual acuity worse than 6/60 and almost a third (29%) had no perception of light in the injured eye. In all, 40% retained acuity of 6/18 or better and only 7% had acuity between 6/60 and 6/18. The small number of cases with intermediate outcomes in acuity suggests a sort of ‘all or none rule’ relating to the injuries. If the globe is hit, it is rarely salvageable, but if other parts of the orbit take most of the impact, useful vision may be preserved. Of 12 eyes removed as a primary procedure, all were so badly damaged that the procedure we describe as ‘evisceration’ was really the removal of whatever fragments of ocular tissue that could be found in the orbit. Three out of 16 ruptured globes were deemed repairable and none of these came to enucleation although one patient developed sympathetic ophthalmia. After a complicated course of management, this patient eventually had better vision in the injured eye. In Elder's12 study on children, although final visual acuity results were quite good overall, the rubber bullet injury subgroup had by far the worst outcome. Nine out of 10 eyes hit by rubber bullets were left with no perception of light. The devastation caused to globes hit directly by bullets as compared to the other injuries seen suggests that there may be no ‘safe distance’ as far as the eye is concerned. This is reflected in the IDF regulations for use: even at the safe distance they are not to be fired at the head. Ninety percent of fatalities in the Northern Ireland study resulted from bullets that hit the head or neck.1 Hence, the accuracy of these bullets and the aim of the shooter are probably at least as important factors influencing the degree of injury as the firing distance.

That weapons designed to control a riot are likely to cause some serious injuries, even deaths, is hardly a surprise. That eyes are likely to be highly vulnerable to destruction by rubber-coated metal bullets is equally unsurprising. The minimisation of such devastating injury should always remain a high priority to those authorising and using these weapons. Strict compliance with clear rules that are not over-reliant on an individual's judgement under extreme duress is essential. Even under these circumstances, it is likely that many more eyes will be lost through the use of these weapons wherever they continue to be used.

References

Millar R, Rutherford WH, Johnston S, Malhotra VJ . Injuries caused by rubber bullets: a report on 90 patients. Br J Surg 1975; 62: 480–486.

Cohen MA . Plastic bullet injuries of the face and jaws. S Afr Med J 1985; 68: 849–852.

Hiss Y, Hellman FN, Kahana T . Rubber and plastic ammunition lethal injuries: the Israeli experience. Med Sci Law 1997; 37: 139–144.

Rocke L . Injuries caused by plastic bullets compared with those caused by rubber bullets. Lancet 1983; I: 919–920.

Metress EK, Metress SP . The anatomy of plastic bullet damage and crowd control. Int J Health Serv 1987; 17: 333–342.

B'Tselem (The Israeli Information Centre for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories). ‘Death Foretold’ Information Sheet. December 1998.

Evaluation of the use of Force in Israel, Gaza and the West Bank. Medical and forensic investigation. Physicians for Human Rights Report, 3 November 2000.

Israel and the occupied territories. Excessive use of lethal force. Amnesty International Report, 19 October 2000.

Pocket Book for Soldiers Serving in the Central Command. 25 June 1977. Headquarters of Education, Command Operations, Interior Department, Israeli Defence Force.

Kirschner RH . Forensic aspects of rubber bullet injuries. In: B'Tselem (ed). Illusions of Restraint—Human Rights Violations during the events in the Occupied Territories 29 September–2 December 2000.

Jaouni ZM, O'Shea JG . Civilian eye casualties in East Jerusalem and the Occupied Territories. Med Confl Surviv 1996; 12: 138–148.

Elder MJ . Penetrating eye injuries in children of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Eye 1993; 7: 429–432.

Population, Housing and Establishment Census December 1997, and Population Indicators mid-2001. Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Ramallah, PS.

Insaleco R (ed). National Statistics Annual Abstract 2002. The Stationary Office: London, 2002.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Originally presented as a poster at the Royal College of Ophthalmologists Congress 2001

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lavy, T., Asleh, S. Ocular rubber bullet injuries. Eye 17, 821–824 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700447

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700447

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Spectrum of injuries with “less-lethal” beanbag weapons: pictorial essay

Emergency Radiology (2022)

-

Ocular trauma by kinetic impact projectiles during civil unrest in Chile

Eye (2021)

-

Less-Lethal Weapons Resulting in Ophthalmic Injuries: A Review and Recent Example of Eye Trauma

Ophthalmology and Therapy (2020)

-

Facial fractures caused by less-lethal rubber bullet weapons: case series report and literature review

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (2017)

-

Indications for bullet removal: overview of the literature, and clinical practice guidelines for European trauma surgeons

European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery (2012)