Abstract

Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have created a paradigm shift in discovering genetic associations for common diseases and phenotypes, but it is unclear whether the thousands of candidate genetic association studies performed in the pre-GWAS era had found any reliable associations for common diseases and phenotypes. We aimed to systematically evaluate whether loci proposed to harbor candidate associations before the advent of GWASs are replicated in GWASs. The GWAS data published through August, 2008 and included in the NHGRI catalog were screened and variants in candidate loci were selected on the basis of statistical significance (P<0.05) to create a list of independent, non-redundant associations. Altogether, 159 articles on GWASs were evaluated, 100 of which addressed past proposed candidate loci. A total of 291 independent, nominally significant (P<0.05) candidate gene associations were assembled after keeping only the SNP with lowest P-value for each locus and each phenotype; 108 of those had P<10−3 for association and 41 had P<10−7. A total of 22 of these 41 candidate gene associations pertained to binary phenotypes with a median odds ratio=2.91 (IQR: 1.82–4.6) and median minor allele frequency=0.17 (IQR: 0.12–0.29) in Caucasians; for comparison, 60 new associations of binary outcomes with P<10−7 discovered in the same GWASs had much smaller effects (median odds ratio 1.30, IQR: 1.18–1.58) and modestly larger minor allele frequencies (median 0.27, IQR: 0.15–0.43). Overall, few of the numerous genetic associations proposed in the candidate gene era have been replicated in GWASs, but those that have been conclusively replicated have large genetic effects that should not be discarded.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The search for common genetic variants influencing the risk of common diseases and phenotypes of medical interest has undergone a major paradigm shift. Until some years ago, the effort of discovering new genetic associations was dominated by targeted approaches in which specific genes and variants were chosen on the basis of known or suspected biological considerations, or at best by perusal of selected areas of the genome (eg, those giving strong signals in linkage scans).1 These approaches have had limited success in yielding conclusive results for the proposed ‘candidate gene’ associations.2 Nevertheless, a large literature of candidate gene associations was generated and continues to be published, with over 7000 articles annually.3 Given a relatively poor replication record, the credibility of most of these associations has been questioned.4, 5

Meanwhile, genome-wide association studies (GWASs) rapidly evaluate hundreds of thousands of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across the whole genome, in an agnostic manner, ie, without any prior predilection for specific loci.6, 7 GWASs have markedly accelerated the pace of discovery of associations with very strong statistical support.8 The enthusiasm about newly discovered loci has left the previously proposed candidate variants in a state of uncertainty. Should we just disregard these candidate associations that formed the corpus of genetic epidemiology until recently and that continue to be studied in thousands of papers?

In theory, well-conducted GWASs offer an excellent opportunity to systematically evaluate, and often with very good coverage,9 genetic loci that were previously proposed as candidates in the older literature. Here, we aimed to systematically record and evaluate previously proposed candidate loci that have been replicated in GWASs.

Materials and methods

Definitions

We used a broad definition of a ‘candidate’ locus (gene/region) as any gene or specific region that has been proposed to be potentially associated with any phenotype before being proposed by any agnostic GWAS. We accepted associations regardless of whether the impetus to study them had been derived from biological reasoning, functional data, in vitro or animal work, linkage signals, or other types of research. We also considered associations regardless of whether the same exact SNPs had been evaluated in the candidate gene era studies and in the GWASs, provided that the same gene or region was involved and the GWAS investigators acknowledged that this was a locus already proposed in the candidate literature. In addition, we accepted situations in which a SNP belonged to a gene other than a candidate one, but it was in linkage disequilibrium with polymorphisms of a candidate gene, as reported by the authors. Genes for which putative associations originated only from evidence other than human population association studies (eg, animals studies or functional in vitro data) were accepted only when there was an a priori plan to look at them before obtaining the GWAS results. We excluded gene variants in which the animal or functional data were invoked only after they had been discovered to be associated in GWAS. In addition, we focused only on common variants, excluding rare variants. We accepted the definition of each of the GWAS articles on what are considered to be common variants, and we recorded the minor allele frequency (MAF) for each variant according to HapMap (release 27) and NCBI dbSNP data for Caucasian populations.

Study selection and eligibility criteria for GWASs

The online Catalog of Published GWASs of NHGRI (www.genome.gov/gwastudies) was searched for eligible studies published until August 01, 2008 (last update access September 15, 2008). Furthermore, references of the eligible studies were screened for any other study meeting the eligibility criteria that were not listed in the catalog.

The GWAS articles were eligible if they genotyped more than 1 00 000 SNPs, spanning across the whole genome, in the first stage in, at least, one human population, in pools or individuals, and had analyzed at least one phenotype. Some of the eligible included studies eventually ended with less than 1 00 000 successfully genotyped SNPs after data-quality surveillance procedures, but this was not considered a reason for excluding them. We also included follow-up publications and meta-analyses of GWASs that reported genotyping data on candidate variants from the stage 1 of GWASs that had not been reported in the primary GWAS publications. We excluded genome-wide studies on copy-number variants and studies that included only family-based designs in the first stage.

Availability and selection of data for variants in candidate loci

We scrutinized both the published articles and online supplements of all eligible studies for any mention of candidate genes/regions. When any such mention was made, we perused the text and the corresponding references, if any, to ensure that this was not an association that had first appeared in other GWASs before any candidate gene study had been performed. In addition, we queried the NHGRI catalog (www.genome.gov/gwastudies) and the HuGE Navigator database10 to exclude genes that had been first proposed by GWASs. Whenever any mention was made in the GWAS articles on the past candidate association(s), we examined whether this was just a simple reference without providing any data, or whether any kind of data were also given. We noted in particular whether there was a preformed list of candidate genes; whether the stage 1 platform had been specifically enriched to add genotyping for variants considered to represent candidate genes; and whether the threshold used for reporting data on candidate genes/regions was different compared with the one used for the other loci.

Data extraction for quantitative information

We considered only variants that were related to a specific candidate gene or particular regions, such as a specific intergenic region, which were highlighted by previous studies, rather than a region spanning many genes. Exception to the above were specific clusters (eg, HLA, APOE, APOA, β-globin, and CYP2C), even though these encompass several genes. A total of 12 GWASs presented data only on candidate variants belonging to large non-specific chromosomal regions (eg, regions 2q31, 20q, and so on) that showed linkage in previous studies.

For those GWASs with stage-1 numerical data for at least one candidate variant, we identified for each variant with a stage-1 P-value <0.05, the gene locus, the SNP, and the P-value. Four GWASs reported no nominally significant associations for candidate loci (all P-values>0.05). From the others, we isolated one SNP per locus with the lowest P-value. When more than one phenotype had been probed for association with a single candidate variant in a study, each phenotype was accounted for separately. We considered P-values uncorrected for multiple comparisons. When both unadjusted and adjusted (for covariates) analyses were presented, we preferred the former. In addition, genotypic P-values were preferred over trend ones. Finally, we considered the combined stage-1 results, if they were available, for the studies that genotyped two or more distinct populations in the first stage. If not, the lowest P-value for each SNP across the different cohorts was recorded.

A number of additional steps were taken to create a list of independent, non-redundant associations, free of duplicates consisting of the same candidate locus and the same or similar/related phenotype (for details, see Supplementary Methods).

The resulting list was examined to identify whether the candidate loci had evidence from at least one previous human population study on the same or some related phenotype(s) preceding the GWAS. When no such evidence was found, candidate status had been assigned apparently on the basis of other (animal, functional, and so on) considerations. For previous human population studies, we queried the HuGE Navigator database,10 PubMed (www.pubmed.gov), PharmGKB (www.pharmgkb.org), AlzGene,11 and SzGene database12.

For each of the replicated candidate associations with P-value<10−7, we searched the HuGE Navigator database10 to record the number of studies published on the association of the specific gene and the same or a similar/related phenotype until the year before the publication of the GWAS. We also assessed whether the specific gene–phenotype association had been initially derived from a linkage study or whether there was, at least, suggestive evidence for them in linkage studies. Finally, we recorded whether Mendelian mutations of the specific gene have been reported in association with the same or a similar/related phenotype, according to the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim).

Data extraction process

The series of actions taken for the selection and extraction of quantitative information is shown in Supplementary Figure 1. Two investigators (KCMS, NAP) perused the studies for eligibility and extracted the data. Discrepancies were resolved by a third investigator (JPAI).

Analyses

We present descriptives on the availability, selection rules used, and reporting of candidate loci in the eligible GWASs. We present the distribution of P-values for the accrued list of independent associations of candidate loci.

For the SNPs that pertained to binary outcomes, we also recorded or calculated the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval and a Bayesian credibility method was applied13, 14 (for details, see Supplementary Methods).

Using the NHGRI catalog, we also recorded the GWAS-discovered associations for binary phenotypes with robust statistical support (P<10−7) that were observed in the 100 GWASs that had also addressed candidate gene associations (for details, see Supplementary Methods). Finally, we obtained data from HapMap on the MAFs in Caucasians (CEU) of these newly discovered associations for comparison with the MAFs of candidate loci with P-values <10−7 using the Mann–Whitney U test.

Results

Eligible studies and data on candidates

We identified 173 potentially eligible articles on GWASs using the NHGRI list, 159 of which were eligible for our analyses (Supplementary Figure 2). Of those, in 32 (20%) there was no mention of past candidate variants and in another 27 (17%) the authors commented on the existence of previously proposed associations, but no GWAS-derived data were given. Of the remaining 100 GWASs (Supplementary references) with data on candidates, two provided non-numerical comments and quantitative data on candidate loci were given in 98 studies (62%).

In 52 studies, results on candidate loci were reported according to less strict statistical significance thresholds compared with those applied for other loci. The authors had selected the candidate variants to report on the basis of a clearly stated preformed list in 37 (37%) studies. In 12 of these 37 studies, results were presented for all candidates considered, in another 22 studies, results were reported according to specific thresholds, whereas the selection on what to present was unclear in the remaining three studies. In four studies, additional SNPs, apart from those present on the main platform, were genotyped to enhance coverage of some candidate loci.

Statistically significant SNPs in candidate loci

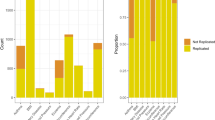

Some GWASs reported on candidate gene associations for many SNPs in the same locus and/or for several similar or related phenotypes, and some associations and loci had been targeted by two or more GWASs. In these cases, we selected the single lowest presented P-value for any related phenotype on the same candidate locus. The distribution of nominally significant P-values (<0.05) in the GWASs for the compiled 291 independent, non-redundant association is shown in Figure 1 and details appear in Supplementary Table 1. Of the 291 associations, 108 had P<10−3 and 41 of these 108 associations had P<10−7. Of all SNPs, 77.4% had MAF>0.10, 14.6% had MAF ranging from 0.05 to 0.10, and 8% had MAF<0.05. The 291 independent associations pertained to 233 different loci plus the HLA region and a wide variety of different types of phenotypes (Supplementary Table 1). For 32 genes plus the HLA region, nominally significant associations (P<0.05) were recorded on more than one type of phenotype, suggesting potential pleiotropic effects. Besides HLA, which was associated with 11 different types of phenotypes, another three gene loci (ADRB2, APOE, and ESR1) had nominally significant associations with four different types of phenotypes each.

For 32 of the 41 associations with P-value <10−7 (not including the HLA and β-globin region variants), the median number of pre-GWAS publications per gene–phenotype association was 4 (IQR: 2.75–20). However, there was large variability and although six associations had only a single previous candidate study, there were 797 publications on APOE and Alzheimer's disease. Six of the 32 associations referred to situations in which variants in a gene seemed to directly regulate the levels of the protein produced by that gene (ICAM-1, CRP, YKL-40, cystatin C, factor VII, sIL-6R). Eight associations (Supplementary Table 2) were originally discovered through linkage studies. Another one association (APOE/Alzheimer's disease) would have modest/suggestive linkage in its chromosomal locus in genome linkage scans,15 although it was originally discovered through association analyses. Similarly, PTPN22 was initially found to be associated with type 1 diabetes in an association study. Then, association was also observed to exist with other autoimmune diseases (rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus) for which retrospectively modest linkage signals had been observed in the respective chromosomal area (1p13).16, 17 Mendelian effects have been reported for 16 of the 32 associations (Supplementary Table 2). Only one of the 32 associations (regulation of CRP levels by an APOE variant) had no precedent of a Mendelian effect or linkage signal and referred to the regulation of the levels of a different protein than the protein produced directly by the gene of interest.

Magnitude of effects and Bayes factors for ORs

Figure 2a shows the distribution of 70 ORs and their 95% confidence intervals for the subset of independent binary-phenotype associations with previous human population studies on the same gene–phenotype pair (Supplementary Table 3). The median OR was 1.50 (IQR: 1.28–2.38). Seven SNPs had an OR value above 5 and another 21 had an OR value above 2. In a sensitivity analysis excluding the seven OR values above 5, the median OR was still 1.45 (IQR: 1.27–1.95).

Magnitude of genetic effects in 100 genome-wide association studies (GWASs): (a) Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for independent, non-redundant associations of candidate loci with binary phenotypes for which previous human population studies had been performed. Odds ratios could be obtained for 70 of 84 eligible associations; (b) Comparison of odds ratios of new GWAS-discovered versus candidate associations with P-values <10−7 for binary phenotypes.

Bayes factors under different prior assumptions are also shown for the associations listed in Supplementary Table 3. Of the 70 listed associations, the Bayes factor was <0.10 for 40 of them under, at least, one set of assumptions, suggesting that for those associations the odds of the association being true increased over 10-fold by the results of the genome-wide investigation, compared to what one thought before that study. Conversely, for 30 associations (including the majority of the nominally statistically significant candidate associations on obesity, coronary heart disease, and Alzheimer's disease), the Bayes factor was unimpressive (>0.1) under all assumptions, suggesting poor credibility of the proposed associations.

Genetic effects in robustly replicated candidate and new GWAS-discovered loci

A total of 22 of the 70 candidate associations with binary outcomes had P<10−7 in the GWASs. Examination of the NHGRI catalog showed that the 100 GWASs that provided results on past candidate associations had led to the discovery of 60 independent, non-redundant associations with binary phenotypes with equally robust statistical support (P<10−7; Supplementary Table 4).

Although the newly discovered loci overall far outnumbered the previously proposed candidate ones by 3 to 1, there were differences in the relative preponderance of candidate versus novel loci for various disease phenotypes (Table 1). For cancer phenotypes, coronary artery disease, restless leg syndrome, bipolar disorder, and gallstone disease, all the loci were newly discovered, with no variants in previously proposed candidate loci reaching P<10−7. In inflammatory bowel disease and type 2 diabetes, there was a strong preponderance of newly discovered loci, with few validated candidate genes. Conversely, there was a more balanced picture with both candidate and newly discovered loci for pigmentation phenotypes and in most autoimmune diseases. Finally, for Alzheimer's disease and statin-induced myopathy, the sole locus with strong support had already been proposed in the candidate era.

Among associations with robust statistical support, the magnitude of the effects was on average much larger for the 22 candidates than for the 60 GWAS-discovered loci (P<0.00001; Figure 2b). The median OR was 2.91 (IQR: 1.82–4.6) for the candidate versus only 1.30 (IQR: 1.18–1.58) for the GWAS-discovered associations. When we examined all 77 non-redundant independent associations for binary phenotypes discovered with documented P<10−7 across all the 159 GWASs (including also those that did not address candidate loci at all), the median OR was 1.32 (IQR: 1.19–1.59), which was still much smaller than the magnitude of the effects for the 22 associations from past candidate loci.

The MAF in Caucasians was smaller for the 22 associations than for the 60 GWAS-discovered associations, but even though the difference was nominally significant (P=0.008), the absolute difference was not impressive (median 0.17; (IQR: 0.12–0.29) versus 0.27; (IQR: 0.15–0.43)). MAF values of 0.05 or less were seen only in one of the 22 SNPs representing candidate loci and four of the 60 SNPs representing new GWAS-derived discoveries.

Discussion

We have accumulated data from 100 GWASs that addressed previously proposed candidate gene loci. Even though the reporting of candidate loci in these GWASs was not always systematic or comprehensive, we have cataloged a substantial number of candidate gene associations with considerable support for association in data sets of GWASs.

This catalog is definitely not complete. Each of the evaluated GWASs used different criteria and thresholds for reporting on previously proposed associations. Furthermore, some associations may not be replicated in GWASs due to suboptimal representation and coverage of the culprit candidate variants among the tag-SNPs used in the high-throughput platforms. In addition, most associations of common genetic variants with complex phenotypes have weak effects and a GWAS may be underpowered to replicate them. For example, a GWAS with 1000 cases and 1000 controls has 12% power to detect a per-allele OR of 1.5 at α=10−7 for MAF of 10%, and the power increases to 85% for a MAF of 40%. Power would be negligible for detecting candidate gene associations with ORs of 1.2 or less, even for very common variants. Therefore, the replicated candidate variants with P<10−7 are likely to be heavily selected in favor of those with the largest effect sizes and substantial MAFs. Finally, almost all GWASs analyzed have been performed in Caucasian populations and candidate gene associations that are relatively specific to non-Caucasian ancestry may have been missed.

Future GWASs may benefit from examining previously proposed candidate gene loci in a more systematic manner, as the replication status of some of these may still be open to question and debate. Moreover, even for loci that are generally accepted, their exact genetic architecture may still be unknown and warrant further replication and detailed study. Detailed fine mapping and resequencing of discovered loci has suggested that in many cases one can identify multiple independent markers.18, 19, 20 Systematic databases, such as the HuGE Navigator,10 are available that can help create comprehensive lists of previously proposed loci and synopses of the genetic association literature may also be helpful to keep track of the evidence.11, 12, 21

The thresholds at which past candidate loci should be claimed to be robustly replicated in GWAS platforms can be debated. Some may argue that similar stringent thresholds such as those proposed for newly discovered variants may be needed, eg P<10−7 or even lower.22, 23 However, this may be too stringent a threshold for loci that have already been proposed and tested for association in the past, even if not the same exact SNPs have been assessed. At the other end of the spectrum, a very lenient threshold, eg P<0.05, for isolated replication, will probably result in many false positives. Furthermore, one should caution that whenever associations are selected on the basis of statistical significance thresholds, effect sizes of the selected associations that pass the required threshold may be inflated compared with the true effect.24, 25 However, this is likely to affect both candidate and newly discovered associations and is unlikely to invalidate the observation that validated candidate gene variants had much larger ORs than the newly discovered variants. In the new wave of discoveries, presently emerging through meta-analyses of multiple GWAS, effects may be even smaller.26, 27 Future analyses of rare variants might, nevertheless, produce stronger signals with considerable effect sizes. With the currently available GWAS-derived data, the impact of candidate gene variants on the proportion of variance explained may be larger, yet still limited in average, than the respective impact of newly discovered GWAS signals.

We noted that half of the robustly replicated candidate associations were in genes that have known mutations producing relevant phenotypes. This may suggest that genes with known important mutations need to be screened with more in-depth sequencing for the recognition of additional common or rare variants that may affect the relevant phenotypes. Moreover, a considerable number of robustly replicated candidate associations are in areas that have given strong signals in linkage scans. It has been proposed that one may use linkage information to pre-weigh favorably the respective areas in GWAS analyses.28 In some cases, we found pleiotropy with effects on several diseases with similar pathogenesis. Pleiotropic effects also need further study by examining systematically related phenotypes once an association has been strongly replicated with one particular phenotype. Finally, it is not surprising that the list of robustly replicated associations should contain some situations in which a gene variant directly regulates the levels of the protein produced by that gene. Otherwise, proposed candidate associations without such Mendelian or linkage precedent evidence may have low credibility.

The relative importance of previously proposed candidate loci differs depending on the phenotype. Despite a huge literature on cancer candidate genes,29, 30 candidate associations with highly definitive evidence are sparse, whereas there is a flurry of newly discovered loci. For coronary artery disease,31, 32 a huge candidate literature hardly left any strongly credible signals. Conversely, the picture is more balanced for autoimmune diseases, for which candidate genes have strong documented effects, mainly represented by the MHC region. Finally, for some phenotypes, such as Alzheimer's disease and pharmacogenetic associations (eg statin-induced myopathy or anticoagulant dosage and bleeding risk),33 GWASs are still unable to produce additional associations with the robustness of those proposed already in the candidate era. Moreover, in the current efforts of full sequencing and with increasing emphasis placed on rare variants, candidate genes may also find some rekindled interest, in which focused evaluation of specific genes may be one option to reduce the multiplicity of analyses for rare variants, and in which otherwise power to detect association is more limited.34 Finally, both candidate and agnostic-derived genes may contribute to understanding of pathogenesis pathways, but it should be acknowledged that the identification of the true culprits and their biological function is often very difficult both in the candidate-gene approach and in the agnostic GWAS setting.35, 36

We acknowledge that here we made no effort to select functional variants from each locus, as this would have been usually futile given the limited information available in each of the GWASs that we analyzed and the difficulty and subjectivity in prioritizing functional importance. Another limitation is that for each candidate locus, it is possible that there may be several recombination hotspots defining different haplotype blocks and more than one independent signal may exist in the same locus. Furthermore, the catalog of replicated candidate loci would be larger, if all GWASs systematically reported on candidate loci and data were meta-analyzed across several GWASs.37, 38 What we have cataloged probably underestimates the number of GWAS-replicated candidate loci, but offers an indicative sample of replicated signals. On the other end of the spectrum, when GWAS’ results are considered, numerous proposed candidate associations turn out to be false positives, but the evaluation of this large volume of non-replicated associations was beyond the scope of this study.

Overall, although GWASs have unquestionably led to a dramatic paradigm shift in discovering genetic associations, there is still some useful evidence to be gleaned from previously proposed candidate associations. Thousands of studies are still performed on past candidate loci, and unfortunately much of this research may be chasing futile, non-validated associations. Focusing candidate gene research efforts on those loci that are also systematically validated in GWAS platforms may improve the efficiency of this huge research agenda and help expedite the successful translation of this accumulating information.

References

Cordell HJ, Clayton DG : Genetic association studies. Lancet 2005; 366: 1121–1131.

Hirschhorn JN, Lohmueller K, Byrne E, Hirschhorn K : A comprehensive review of genetic association studies. Genet Med 2002; 4: 45–61.

Lin BK, Clyne M, Walsh M et al: Tracking the epidemiology of human genes in the literature: the HuGE Published Literature database. Am J Epidemiol 2006; 164: 1–4.

Ioannidis JP, Ntzani EE, Trikalinos TA, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG : Replication validity of genetic association studies. Nat Genet 2001; 29: 306–309.

Ioannidis JP : Genetic associations: false or true? Trends Mol Med 2003; 9: 135–138.

Cardon LR : Genetics. Delivering new disease genes. Science 2006; 314: 1403–1405.

McCarthy MI, Abecasis GR, Cardon LR et al: Genome-wide association studies for complex traits: consensus, uncertainty and challenges. Nat Rev Genet 2008; 9: 356–369.

Manolio TA, Brooks LD, Collins FS : A HapMap harvest of insights into the genetics of common disease. J Clin Invest 2008; 118: 1590–1605.

Barrett JC, Cardon LR : Evaluating coverage of genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 2006; 38: 659–662.

Yu W, Gwinn M, Clyne M, Yesupriya A, Khoury MJ : A navigator for human genome epidemiology. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 124–125.

Bertram L, McQueen MB, Mullin K, Blacker D, Tanzi RE : Systematic meta-analyses of Alzheimer disease genetic association studies: the AlzGene database. Nat Genet 2007; 39: 17–23.

Allen NC, Bagade S, McQueen MB et al: Systematic meta-analyses and field synopsis of genetic association studies in schizophrenia: the SzGene database. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 827–834.

Ioannidis JP : Calibration of credibility of agnostic genome-wide associations. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2008; 147B: 964–972.

Ioannidis JP : Effect of formal statistical significance on the credibility of observational associations. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 168: 374–383.

Kehoe P, Wavrant-De Vrieze F, Crook R et al: A full genome scan for late onset Alzheimer's disease. Hum Mol Genet 1999; 8: 237–245.

Gaffney PM, Kearns GM, Shark KB et al: A genome-wide search for susceptibility genes in human systemic lupus erythematosus sib-pair families. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95: 14875–14879.

Jawaheer D, Seldin MF, Amos CI et al: Screening the genome for rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility genes: a replication study and combined analysis of 512 multicase families. Arthritis Rheum 2003; 48: 906–916.

Gudbjartsson DF, Arnar DO, Helgadottir A et al: Variants conferring risk of atrial fibrillation on chromosome 4q25. Nature 2007; 448: 353–357.

Haiman CA, Patterson N, Freedman ML et al: Multiple regions within 8q24 independently affect risk for prostate cancer. Nat Genet 2007; 39: 638–644.

Graham RR, Kyogoku C, Sigurdsson S et al: Three functional variants of IFN regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) define risk and protective haplotypes for human lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 6758–6763.

Ioannidis JP, Gwinn M, Little J et al: A road map for efficient and reliable human genome epidemiology. Nat Genet 2006; 38: 3–5.

Pe′er I, Yelensky R, Altshuler D, Daly MJ : Estimation of the multiple testing burden for genomewide association studies of nearly all common variants. Genet Epidemiol 2008; 32: 381–385.

Hoggart CJ, Clark TG, De Iorio M, Whittaker JC, Balding DJ : Genome-wide significance for dense SNP and resequencing data. Genet Epidemiol 2008; 32: 179–185.

Ioannidis JP : Why most discovered true associations are inflated. Epidemiology 2008; 19: 640–648.

Zollner S, Pritchard JK : Overcoming the winner's curse: estimating penetrance parameters from case-control data. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 80: 605–615.

Zeggini E, Weedon MN, Lindgren CM et al: Replication of genome-wide association signals in UK samples reveals risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Science 2007; 316: 1336–1341.

Zeggini E, Scott LJ, Saxena R et al: Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large-scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 638–645.

Manolio TA, Collins FS, Cox NJ et al: Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature 2009; 461: 747–753.

Dong LM, Potter JD, White E, Ulrich CM, Cardon LR, Peters U : Genetic susceptibility to cancer: the role of polymorphisms in candidate genes. JAMA 2008; 299: 2423–2436.

Vineis P, Manuguerra M, Kavvoura FK et al: A field synopsis on low-penetrance variants in DNA repair genes and cancer susceptibility. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009; 101: 24–36.

Ntzani EE, Rizos EC, Ioannidis JP : Genetic effects versus bias for candidate polymorphisms in myocardial infarction: case study and overview of large-scale evidence. Am J Epidemiol 2007; 165: 973–984.

Morgan TM, Krumholz HM, Lifton RP, Spertus JA : Nonvalidation of reported genetic risk factors for acute coronary syndrome in a large-scale replication study. JAMA 2007; 297: 1551–1561.

Wang L, Weinshilboum RM : Pharmacogenomics: candidate gene identification, functional validation and mechanisms. Hum Mol Genet 2008; 17: R174–R179.

Bodmer W, Bonilla C : Common and rare variants in multifactorial susceptibility to common diseases. Nat Genet 2008; 40: 695–701.

Ioannidis JP, Thomas T, Daly MJ : Validating, augmenting and refining genome-wide association signals. Nat Rev Genet 2009; 10: 318–329.

McCarthy MI, Hirschhorn JN : Genome-wide association studies: potential next steps on a genetic journey. Hum Mol Genet 2008; 17 (R2): R156–R165.

Zeggini E, Ioannidis JP : Meta-analysis in genome-wide association studies. Pharmacogenomics 2009; 10: 191–201.

Richards JB, Kavvoura FK, Rivadeneira F et al: Collaborative meta-analysis: associations of 150 candidate genes with osteoporosis and osteoporotic fracture. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: 528–537.

Acknowledgements

We thank P Gaffney, S Shifman, D van Heel, and R Gibson for offering helpful clarifications on their data. This study is supported by a PENED grant from the European Union and the General Secretariat for Research and Technology, Greece (to NAP) (PI: JPAI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Siontis, K., Patsopoulos, N. & Ioannidis, J. Replication of past candidate loci for common diseases and phenotypes in 100 genome-wide association studies. Eur J Hum Genet 18, 832–837 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2010.26

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2010.26

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Identification of quantitative trait loci and associated candidate genes for pregnancy success in Angus–Brahman crossbred heifers

Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology (2023)

-

Two GWAS-identified variants are associated with lumbar spinal stenosis and Gasdermin-C expression in Chinese population

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Genome-wide association study (GWAS) of human host factors influencing viral severity of herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2)

Genes & Immunity (2019)

-

Association of Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) Identified SNPs and Risk of Breast Cancer in an Indian Population

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Association of the glucokinase gene promoter polymorphism -30G > A (rs1799884) with gestational diabetes mellitus susceptibility: a case–control study and meta-analysis

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2015)