Abstract

Background/Objectives:

Dietary factors have been hypothesized to influence the risk of preeclampsia. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between maternal intake of sugar and foods with a high content of added or natural sugars and preeclampsia.

Subjects/Methods:

A prospective study of 32 933 nulliparous women in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study, conducted by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Participants answered a general health questionnaire and a validated food frequency questionnaire during pregnancy. Information about preeclampsia was obtained from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway. The relative risk of preeclampsia was estimated as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and adjusted for known confounders.

Results:

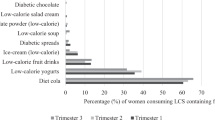

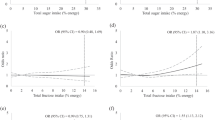

The intake of added sugar was higher in women who developed preeclampsia than in healthy women in the unadjusted analysis, but not in the adjusted model. Of food items with a high content of added sugar, sugar-sweetened carbonated and non-carbonated beverages were significantly associated with increased risk of preeclampsia, both independently and combined, with OR for the combined beverages 1.27 (95% CIs: 1.05, 1.54) for high intake (>=125ml/day) compared with no intake. Contrary to this, intakes of foods high in natural sugars, such as fresh and dried fruits, were associated with decreased risk of preeclampsia.

Conclusions:

These results suggest that foods with a high content of added sugar and foods with naturally occurring sugars are differently associated with preeclampsia. The findings support the overall dietary advice to include fruits and reduce the intake of sugar-sweetened beverages during pregnancy.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lain KY, Roberts JM . Contemporary concepts of the pathogenesis and management of preeclampsia. JAMA 2002; 287: 3183–3186.

Nilsen RM, Vollset SE, Gjessing HK, Skjaerven R, Melve KK, Schreuder P et al. Self-selection and bias in a large prospective pregnancy cohort in Norway. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2009; 23: 597–608.

Redman CW, Sargent IL . Immunology of pre-eclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol 2010; 63: 534–543.

Xu H, Shatenstein B, Luo ZC, Wei S, Fraser W . Role of nutrition in the risk of preeclampsia. Nutr Rev 2009; 67: 639–657.

Roberts JM, Balk JL, Bodnar LM, Belizan JM, Bergel E, Martinez A . Nutrient involvement in preeclampsia. J Nutr 2003; 133: 1684S–1692SS.

Rumbold A, Duley L, Crowther CA, Haslam RR . Antioxidants for preventing pre-eclampsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008 CD004227.

Clausen T, Slott M, Solvoll K, Drevon CA, Vollset SE, Henriksen T . High intake of energy, sucrose, and polyunsaturated fatty acids is associated with increased risk of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001; 185: 451–458.

Qiu C, Coughlin KB, Frederick IO, Sorensen TK, Williams MA . Dietary fiber intake in early pregnancy and risk of subsequent preeclampsia. Am J Hypertens 2008; 21: 903–909.

Frederick IO, Williams MA, Dashow E, Kestin M, Zhang C, Leisenring WM . Dietary fiber, potassium, magnesium and calcium in relation to the risk of preeclampsia. J Reprod Med 2005; 50: 332–344.

Arola L, Bonet ML, Delzenne N, Duggal MS, Gomez-Candela C, Huyghebaert A et al. Summary and general conclusions/outcomes on the role and fate of sugars in human nutrition and health. Obes Rev 2009; 10 (Suppl 1), 55–58.

Brantsæter AL, Haugen M, Samuelsen SO, Torjusen H, Trogstad L, Alexander J et al. A dietary pattern characterized by high intake of vegetables, fruits, and vegetable oils is associated with reduced risk of preeclampsia in nulliparous pregnant Norwegian women. J Nutr 2009; 139: 1162–1168.

Magnus P, Irgens LM, Haug K, Nystad W, Skjaerven R, Stoltenberg C . Cohort profile: The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). Int J Epidemiol 2006; 35: 1146–1150.

Irgens LM The Medical Birth Registry of Norway Epidemiological research and surveillance throughout 30 years. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2000; 79: 435–439.

Meltzer HM, Brantsæter AL, Ydersbond TA, Alexander J, Haugen M . Methodological challenges when monitoring the diet of pregnant women in a large study: experiences from the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). Matern Child Nutr 2008; 4: 14–27.

Lauritsen J FoodCalc (online). Available at: http://www.ibt.ku.dk/jesper/foodcalc (accessed February 2006); 2005.

Norwegian Food Safety Authority, Norwegian Directorate of Health, Department of Nutrition - University of Oslo. Matvaretabellen (The Norwegian Food Composition Table). Oslo: Available online at http://www.matportalen.no/Matvaretabellen; 2006.

Brantsæter AL, Haugen M, Alexander J, Meltzer HM . Validity of a new food frequency questionnaire for pregnant women in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). Matern Child Nutr 2008; 4: 28–43.

Brantsæter AL, Haugen M, Rasmussen SE, Alexander J, Samuelsen SO, Meltzer HM . Urine flavonoids and plasma carotenoids in the validation of fruit, vegetable and tea intake during pregnancy in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). Public Health Nutr 2007; 10: 838–847.

Brantsæter AL, Haugen M, Julshamn K, Alexander J, Meltzer HM . Evaluation of urinary iodine excretion as a biomarker for intake of milk and dairy products in pregnant women in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). Eur J Clin Nutr 2009; 63: 347–354.

The Norwegian Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Retningslinjer for svangerskapsomsorgen 2005 (Clinical Guidelines in Obestetrics). Oslo, Norway: Norwegian Medical Association. Available online at: http://www.legeforeningen.no/id/78144.0 (accessed October 2010); 2006.

Klemmensen AK, Olsen SF, Østerdal ML, Tabor A . Validity of preeclampsia-related diagnoses recorded in a national hospital registry and in a postpartum interview of the women. Am J Epidemiol 2007; 166: 117–124.

Saftlas AF, Triche EW, Beydoun H, Bracken MB . Does chocolate intake during pregnancy reduce the risks of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension? Ann Epidemiol 2010; 20: 584–591.

WHO. Diet nutrition, and the prevention of chronic diseases: report of a joint WHO/FAO expert consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003.

Dusse LM, Rios DR, Pinheiro MB, Cooper AJ, Lwaleed BA . Pre-eclampsia: relationship between coagulation, fibrinolysis and inflammation. Clin Chim Acta 2010; 412: 17–21.

Clausen T Maternal and placental factors and risk of preeclampsia: A prospective study of dietary, lipid, hormonal and inflammatory factors (Doctoral Thesis). Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, 2002.

Borzychowski AM, Sargent IL, Redman CW . Inflammation and pre-eclampsia. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2006; 11: 309–316.

O'Keefe JH, Gheewala NM, O'Keefe JO . Dietary strategies for improving post-prandial glucose, lipids, inflammation, and cardiovascular health. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 51: 249–255.

Nettleton JA, Steffen LM, Mayer-Davis EJ, Jenny NS, Jiang R, Herrington DM et al. Dietary patterns are associated with biochemical markers of inflammation and endothelial activation in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 83: 1369–1379.

Sofi F, Cesari F, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A . Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: meta-analysis. BMJ 2008; 337: a1344.

Hu FB, Malik VS . Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes: epidemiologic evidence. Physiol Behav 2010; 100: 47–54.

Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Despres JP, Hu FB . Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation 2010; 121: 1356–1364.

Aeberli I, Gerber PA, Hochuli M, Kohler S, Haile SR, Gouni-Berthold I et al. Low to moderate sugar-sweetened beverage consumption impairs glucose and lipid metabolism and promotes inflammation in healthy young men: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2011; 94: 479–485.

Cohen L, Curhan G, Forman J . Association of sweetened beverage intake with incident hypertension. J Gen Intern Med; e-pub ahead of print 27 April 2012.

Westerterp KR, Goris AH . Validity of the assessment of dietary intake: problems of misreporting. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2002; 5: 489–493.

Olafsdottir AS, Thorsdottir I, Gunnarsdottir I, Thorgeirsdottir H, Steingrimsdottir L . Comparison of women's diet assessed by FFQs and 24-hour recalls with and without underreporters: associations with biomarkers. Ann Nutr Metab 2006; 50: 450–460.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support provided by the Norwegian University of Life Sciences and Sandviks research grant. The Norwegian MoBa is supported by the Norwegian Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education and Research, NIH/NIEHS (contract no NO-ES-75558), NIH/NINDS (Grant no. 1 UO1 NS 047537-01) and the Norwegian Research Council/FUGE (Grant no. 151918/S10). We are grateful to all the participating families in Norway who took part in this ongoing cohort study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Contributors: IB, GAa and ALB planned the study and carried out the statistical analyses; MH estimated all dietary intakes, NH and HMM contributed to the interpretation of the results. IB drafted the manuscript. All authors took part in the preparation of the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Borgen, I., Aamodt, G., Harsem, N. et al. Maternal sugar consumption and risk of preeclampsia in nulliparous Norwegian women. Eur J Clin Nutr 66, 920–925 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2012.61

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2012.61

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Liver ChREBP deficiency inhibits fructose-induced insulin resistance in pregnant mice and female offspring

EMBO Reports (2024)

-

Assessing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in early pregnancy using a substance abuse framework

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

An elevation in serum uric acid precedes the development of preeclampsia

Hypertension Research (2023)

-

Fructose might be a clue to the origin of preeclampsia insights from nature and evolution

Hypertension Research (2023)

-

Maternal nutritional risk factors for pre-eclampsia incidence: findings from a narrative scoping review

Reproductive Health (2022)