Abstract

Data sources

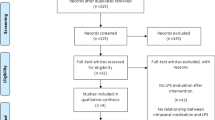

Searches of Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Medline, Embase, six thesis databases (Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations, Proquest Digital Dissertations, OAIster, Index to Theses, Australian Digital Thesis program and Dissertation.com) and one conference report database (BIOSIS Previews) were undertaken. There were no language restrictions.

Study selection

Studies were included in which participants had a noncontributory medical history, presented with mature teeth and radiographic evidence of periapical bone loss (as an indication of pre-operative canal infection), whose selected root canals had not previously received any endodontic treatment, and who had undergone nonsurgical root canal treatment during the study in which calcium hydroxide had also been used to seal in the canals. In addition, it was required that microbiological sampling had been undertaken during the course of treatment, before canal preparation, after canal preparation and after canal medication. Aerobic and anaerobic culturing techniques were performed on all samples. The treatment outcomes were stated in terms of positive and negative canal cultures.

Data extraction and synthesis

All data were extracted in the same manner using a standardised data extraction sheet. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using the standard chi-squared test or Q-statistic. The principal measure of treatment effect (antibacterial efficacy) was risk difference, which is normally defined as the risk in the experimental group minus risk in the control group. For the purpose of this study, it is given as the difference in the proportion of bacteria-positive cultures pre- and post-medication.

Results

Out of the eight studies (257 cases) included, one study used a small control group (in which canals were left empty, and no intracanal medicament was used between appointments). The other seven studies simply compared the frequency of positive cultures before and after calcium hydroxide medication. Six studies demonstrated a statistically significant difference between pre- and postmedicated canals, whereas two did not. There was considerable heterogeneity among studies. The pooled risk difference was 21% (95% confidence intervals, 6–47%. The difference in the proportion of cases positive for bacteria before and after treatment was not statistically significant (P = 0.12).

Conclusions

Based on the current best available evidence, calcium hydroxide has limited effectiveness in eliminating bacteria from human root canals, when assessed by culture techniques. The quest for better antibacterial protocols and sampling techniques must continue to ensure that bacteria can be reliably eradicated prior to obturation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

Endodontic treatment is essentially directed toward the prevention and control of pulpal and periradicular infections. Given the relevance of micro-organisms in the pathogenesis of these lesions, it is clear that the outcome of endodontic therapy depends on their reduction or elimination. Complete chemo-mechanical preparation is considered an essential step in root canal disinfection. Total eradication of bacteria (sterility) is a difficult task to accomplish1 but the use of intracanal medications such as calcium hydroxide has long been thought to maximise the chances of eradicating pathogens from micro-endodontic systems.

The basic theory behind the use of calcium hydroxide is that endodontic pathogens will be unable to survive in the alkaline environment it creates. Indeed, several studies showed total eradication of several bacterial species commonly found in infected root canals when in direct contact with this treatment.2 Its antimicrobial activity is related to the release of hydroxyl ions in an aqueous environment; these are highly oxidising free radicals that show extreme reactivity with many biomolecules.

However, this direct contact is not always possible. At is difficult for calcium hydroxide to dissolve and diffuse in the root canal system and thus its cytotoxicity is limited to the tissues with which it is in direct contact. Its low solubility and diffusibility may make it difficult to cause the rapid and significant increase in pH that would eradicate bacteria located at distant anatomic sites.3

Although the pharmacokinetics of this compound have been well-characterised, this pharmacodynamic problem seems to be overlooked, in turn affecting our understanding of its efficacy in vivo. The effect of buffering systems, acids, proteins, carbon dioxide and dentine chips might all affect the bioavailability of hydroxide ions to diffuse.4 In addition, the interaction between calcium hydroxide and the biofilms coating dentine walls is not well-characterised; it might be hypothesised in this case, as in others, that cells located at the periphery of the biofilm protect those located distant from the surface.

Another unknown in the pharmacodynamics of calcium hydroxide is the period required to optimally disinfect the root canal system. Studies of this have given conflicting results, ranging from 3 months to 2 weeks.5, 6 Negative culture findings do not always indicate sterile root canals, either, because of the limited accessibility to these ‘micro anatomic’ systems, as well as the fact that the sensitivity limit of these cultures is 103–105 cells/ml.

This review aimed to determine the efficacy of calcium hydroxide intracanal medication in eliminating bacteria from human root canals, comparing the effect of treatment with the same canals before treatment. This was measured using bacterial cultures as the outcome for systematic review and meta-analysis. As such, this is a welcome addition to the existing literature. The data extraction was carried out using a standardised data extraction sheet. The inclusion criteria were well-defined and appropriate for the purpose of the study. The insignificant difference between pre- and postmedication in positive cultures adds more evidence of the limited effect of calcium hydroxide in eradicating bacteria from human root canals. Nevertheless, these findings do not discount the use of calcium hydroxide as intracanal medication, particularly in cases where chemomechanical debridement cannot be carried out optimally, such as apexification and perforation repair.

Practice points

Calcium Hydroxide has limited effectiveness in eliminating bacteria from root canals.

References

Siqueira Jr JF, Goncalves RB . Antibacterial activities of root canal sealers against selected anaerobic bacteria. J Endodont 1996; 22:89–90

Bystrom A, Sundqvist G . The antibacterial action of sodium hypochlorite and EDTA in 60 cases of endodontic therapy. Int Endodont J 1985; 18:35–40

Orstavik D, Haapasalo M . Disinfection by endodontic irrigants and dressings of experimentally infected dentinal tubules. Endodont Dent Traumatol 1990; 6:142–149

Haapasalo HK, Siren EK, Waltimo TM, Orstavik D, Haapasalo MP . Inactivation of local root canal medicaments by dentine: an in vitro study. Int Endodont J 2000; 33:126–131

Cvek M, Hollender L, Nord CE . Treatment of non-vital permanent incisors with calcium hydroxide. VI. Clinical microbiological and radiological evaluation of treatment in one sitting of teeth with mature or immature root. Odontologisk Rev 1976; 27:93–108

Barbosa CAM, Goncalves RB, Siqueira JF, Uzeda M . Evaluation of the antibacterial activities of calcium hydroxide, chlorhexidine and camphorated paramonochlorophenol as intracanal medicament. A clinical and laboratory study. J Endodont 1997; 23:297–300

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Dr Chankhrit Sathorn, 720 Swanston Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3010, Australia. E-mail: chankhrit@gmail.com

Sathorn C, Parashos P, Messer H. Antibacterial efficacy of calcium hydroxide intracanal dressing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Endodont J 2007; 40:2–10

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Balto, K. Calcium hydroxide has limited effectiveness in eliminating bacteria from human root canal. Evid Based Dent 8, 15–16 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400467

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400467

This article is cited by

-

Preferences of dentists and endodontists, in Saudi Arabia, on management of necrotic pulp with acute apical abscess

BMC Oral Health (2018)

-

Trial suggests no difference between single-visit and two-visit root canal treatment

Evidence-Based Dentistry (2013)