Abstract

Data sources

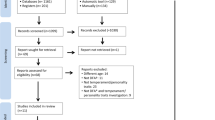

Medline and the Social Science Index Citation databases were searched.

Study selection

Studies had to have used measures of dental anxiety completed by children themselves (≤16 years), been published in English and reported primary data. Non-validated measures, those using proxy measures and non-dentally specific measures were excluded.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were extracted independently using a standardised form. Validity and reliability of the questionnaires were assessed, and measures were evaluated against a theoretical framework of dental anxiety. A qualitative summary of the measures is presented.

Results

Sixty studies met the inclusion criteria. These covered seven ‘trait’ and two ‘state’ measures of dental anxiety used to assess children's dental anxiety over the past decade.

Conclusions

The findings from this systematic review can be used to help guide dental academics, clinicians, psychologists and epidemiologists to choose the most appropriate measure of dental anxiety for their intended use. Future work should involve evaluating the content and developmental validity of existing measures with further consideration given to the use of theoretical frameworks to develop this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

This review of measures of child dental anxiety is timely as there are now a variety of measures available that have been reported over a number of decades, (from the 1970s) and closer attention is being paid to the routine assessment of child dental anxiety in dental health care provision. Within this context the possibility of providing an evidence-based informed protocol to track children with dental fear who are referred to specialist services for assistance to receive dental treatment would improve quality of service delivery. Hitherto the approach to assist children with high levels of dental anxiety has been to use to behavioural management techniques supplemented to varying degrees with pharmacological interventions in the form of inhalation sedation, IV sedation or dental general anaesthesia.1 With the development of behavioural management assessments and a more extensive literature on behavioural approaches to reduce dental anxiety there has been closer attention to adopting psychometrically sound measures of dental anxiety.

This paper systematically reviewed articles over the past decade and found 60 studies that met their criteria of selection. Key areas of interest included the psychometric properties of the selected dental anxiety questionnaires and how these measures matched a theoretical model of Porrit et al's choice. The systematic review presents some key tables that summarise useful descriptions of the various scales to assist researchers in their selection for use in future studies. The new investigator is likely to inspect this article to gain some appreciation of the variety, strengths and limitations of the various child dental anxiety inventories. Hence some important issues of interpretation or omission may be helpful to highlight to further assist the investigator and also point to additional areas for research endeavour.

The review restricts itself to PubMed and Web of Science over the past 10 years. This produced summary data on nine measures. The original papers which presented material of the reliability and validity checks of each scale were obtained in addition, and used to prepare the description and evidence for each measure's quality. The team of reviewers comprised personnel from specialist paediatric dentistry, health psychology, medical sociology and dental public health. A measure not included in the review was the DA5.2 This measure was based upon photographic images which young children (aged three to five years) were able to rate by posting these images directly into three categories via a child-friendly design post-box rating scheme. Some evidence of reliability and validity was presented in the article.

Other psychometric qualities were not commented upon. For example the ‘instrumental’ effects of a scale were not tested in any of the nine reviewed scales with the exception of the MCDAS. A specific study was reported to demonstrate that the completion of the scale did not in itself significantly raise dental anxiety.3 With questions being raised about the use of self-reported measures and their potential influence on the very construct they are attempting to measure, this issue needs greater attention by proponents of dental anxiety measures.

The description of the DAS and MDAS in Table 1 was pooled although there are some important differences. However more importantly neither of these two measures was developed for children. They are adult measures that were simply used for completion by children as young as seven years. The recommendation that might have been applied by the reviewers was to avoid using because of the very limited focus on the child. Admittedly the authors of the review did state explicitly that children were not involved in the development of these two measures.

The review authors alert the reader to the need to adopt a theoretical model to assist with interpretation of the measurement obtained. Certainly a good measure is really only a reflection of the model or theory of the construct under interest.4 It may be assumed that the Five Areas Model was chosen as appropriate since it is based within cognitive behavioural theory and since the various measures are self-reporting/ed. While the reason for this choice is not commented upon it would seem other models, behavioural5 and psycho-analytical,6 could have been considered or at least mentioned.

Two important issues are worth drawing to the reader's attention. First, the use of cut-offs to identify key categories of child patient that might require assistance by specialist services is mentioned in the review, although no measure in the child dental anxiety literature provides a robust validated set of cut-offs. Suggestions have been made and alluded to, but some formal testing is urgently required. Secondly, clinical significance of meaningful change is not mentioned in the review and has not been a feature of the articles in any of the measures presented in the summary table.7 This is a crucial area for development as the service developer needs to be aware when a single case has made a significant change in their reported dental anxiety report. Such techniques are now available from neuropsychology using Bayesian estimators and we wait for developments in the short term for this important information for at least one of the scales that are presented in the review.8

Other issues that could be included in future developments of scales include: coverage of the measurement domain, ease of scoring and interpretation, psychometric translation into useable scoring by researchers and clinicians alike, g-score coefficients, discussion of repeated use and practice effects, factorial structures and invariance testing across settings and child groups (culture, development and gender).

In conclusion, this review brings together the various measures of child dental anxiety which clinicians and researchers may find of value in their work. However readers have additional issues to discuss and contemplate within their teams before arriving at their final selection for their assessment purpose.

References

Boyle CA, Newton T, Milgrom P . Who is referred for sedation for dentistry and why? Br Dent J 2009; 206: 322–323.

Humphris G, Milsom K, Tickle M, Holbrook H, Blinkhorn A . A new dental anxiety scale for 5 year old children (DA5): description and concurrent validity. Health Educ J 2002; 61: 5–19.

Carlsen A, Humphris GM, Lee GTR, Birch RH . The effect of pre-treatment enquiries on child dental patients' post-treatment ratings of pain and anxiety. Psychol Health 1993; 8: 165–174.

Streiner DL, Norman GR . Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. New York: Oxford University Press. 2003

Rachman S. (1990) Fear and courage. New York: Freeman.

Freeman R . A psychodynamic theory for dental phobia. Br Dent J 1998; 184: 170–172.

Jacobson NS, Truax P . Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991; 59: 12–19.

Crawford JR, Garthwaite PH . Comparison of a single case to a control or normative sample in neuropsychology: development of a Bayesian approach. Cogn Neuropsychol 2007; 24: 343–372.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Dr Jenny Porritt, Academic Unit of Oral Health and Development, School of Clinical Dentistry, University of Sheffield, Sheffield S10 2TA, UK. E-mail: jenny.porritt@sheffield.ac.uk

Porritt J, Buchanan H, Hall M, Gilchrist F, Marshman Z. Assessing children's dental anxiety: a systematic review of current measures. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2012; Sep 12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2012.00740.x. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 22970833

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Humphris, G., Freeman, R. Measuring children's dental anxiety. Evid Based Dent 13, 102–103 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400887

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400887