Abstract

Data sources

PubMed and Medline.

Study selection

Relevant studies were identified through a systematic bibliographic search. The databases were searched up to June 2009. If there were additional articles listed in the reference sections of those articles, these additional articles were also obtained and reviewed. Inclusion criteria included the availability of original data from studies, data on the primary outcome (oral cancer, tongue cancer, or oro-pharyngeal cancer), adequate data on maté exposure measurement and sufficient data presented in order to calculate the measure of the association between maté use and cancer. Articles that did not meet these criteria were excluded.

Data extraction and synthesis

Each article was independently evaluated by two reviewers. Both crude and adjusted measures of the association between maté drinking and oral and oro-pharyngeal cancer were highlighted in the review. For the meta-analysis, data were extracted from each study to calculate the unadjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence interval. Summary estimates were calculated using random-effects models.

Results

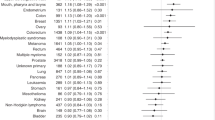

Four case–control studies conducted in Latin America were identified in this review. There were 879 maté users and 1128 non- or low-maté users in those studies with a total of 566 oral and oro-pharyngeal cancers. The adjusted association between maté drinking and oral and oro-pharyngeal cancer was significant within three of those studies. The meta-analysis yielded a significant summary odds ratio (OR) of 2.11 (95% confidence interval = 1.39–3.19). Population Attributable Risk for maté drinking was 16%.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis of case-control studies supports the hypothesis of an association between maté drinking and risk of cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx. However, little is known about whether this increased risk is due to the high temperature of the beverage when consumed or due to certain carcinogenic constituents that are present in maté. More studies are needed before a conclusion can be made on the oral and pharyngeal carcinogenic risk of maté to humans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

Maté is a common beverage worldwide, especially in Latin America and certain parts of the Middle East. The dried leaves and stemlets of the plant are brewed and consumed hot or cold. Several studies have shown that maté drinking is a risk factor for a number of cancers including oral and pharyngeal cancers. Also, there is a strong evidence base linking maté drinking to oesophageal cancer.1, 2, 3 Conversely, maté has been recognised for its antioxidant and anticancer properties. A recent study isolated di-caffeoylquinic acids (diCQAs) from maté leaves to explore their mechanism of action. The results suggest that diCQAs in maté could be potential anti-cancer agents and could mitigate other diseases associated with inflammation.4 With such conflicting data, this review is very relevant and serves to advance our understanding of the association between maté drinking and the risk of oral and pharyngeal cancers.

The review addressed the study question using a well thought out systematic approach.The authors' search strategy included the terms maté, maté drinking, maté beverage, cancer, oral cancer, tongue cancer and oro-pharyngeal cancer. These terms were clearly appropriate for the retrieval of relevant citations. However, the search could have been expanded with the use of medical subject heading (MeSH) terms such as ‘Ilex paraguariensis’ or ‘mouth neoplasms’, which may have retrieved additional studies indexed under these terms in the Medline database. The use of MeSH terms in systematic review searches is consistent with the approach recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration.5 It is important to note that systematic searches should be carefully designed to retrieve as many relevant papers as possible while minimising the retrieval of non-relevant citations.

The four studies included in the review came from two South American countries. Two studies were conducted in Brazil and two were conducted in Uruguay. All four studies recruited hospital controls and the two Uruguayan studies enrolled men only. Three studies showed significant associations between maté drinking and oral cancer. Individual study associations were adjusted for known confounders such as age, smoking and alcohol consumption. However, adjusted summary estimates could not be generated in the meta-analysis since the original data on the distribution of the confounding variables within maté and non-maté groups were unavailable. The authors discussed the adjusted estimates within each study and assessed study quality based on study design, sample size, control selection, adjustment of confounding, exposure measurement and reported data analysis.

The pooled estimate in the meta-analysis indicated a significant two-fold increase (OR = 2.1) of oral and oro-pharyngeal cancer among maté drinkers. This finding is consistent with a recent multisite case-control study6 that examined the relationship between maté consumption and risk of 13 cancer sites in Uruguay. The study found that maté consumption was directly associated with cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract. Furthermore, two of the four studies included in the review7, 8 showed a synergistic effect between maté and cigarette smoking. The two remaining studies provided inconclusive evidence on the effect of beverage temperature on oral cancer risk. Franco and colleagues compared individuals who consumed ‘burning hot’ maté to those who consumed maté at lower temperatures but failed to find a significant association.9 Pintos et al. showed that those who consumed more maté but at a cooler temperature had a higher and significant adjusted relative risk of upper aerodigestive tract cancers compared to those who drank the same amount of maté at a higher temperature.10

Whilst the review competently addresses the highly relevant issue of maté drinking and oral cancers, some limitations are present. The varying exposure measurement units used in included studies presented a challenge when pooling data. In order to minimise this challenge, the authors dichotomised the exposure using the lowest category within each measurement unit as the reference category (either <1 cup/month, <1 l/day, or <1 gourd/day) and pooled all other exposure strata to create one exposure category. Although this approach facilitated data pooling, it is not possible to use the summary estimate to establish an exposure threshold for identifying individuals with elevated cancer risk. In addition, the authors noted that one of studies7 introduced substantial heterogeneity to the meta-analysis. As such, they reported that the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance, was 0% before the study was added and went up to 67% after its addition. This sharp increase may reflect differences in study characteristics and a lack of consistency in results from included studies. Thus, the pooled estimate must be interpreted with caution.

Furthermore, in case-control studies, recruiting representative controls is usually difficult. In all four studies, controls came from hospital settings and it is unknown whether those individuals were representative of their general populations in terms of maté exposure. Moreover, since the four studies came from two countries in Latin America, it is difficult to generalise the findings to other populations. Future research needs to test the consistency of this association in other populations where maté is consumed.

The carcinogenic mechanisms of maté warrant further investigation. Among the potential mechanisms are thermal injury to tissues and the chemical carcinogen content of maté. The temperature of the beverage may damage the mucosa or accelerate metabolic reactions, including those with carcinogenic substances in tobacco and alcohol. Studies that evaluated thermal injury to tissues by hot maté as a potential risk factor for cancer provide conflicting evidence. Indeed, this was the case in two studies from this review. However, findings from a recent systematic review support the thermal injury hypothesis and strongly suggest that high-temperature beverage drinking, in general, increases the risk of oesophageal cancer. In the case of maté, the review showed that oesophageal cancer risk increased with both amount consumed and temperature of maté, and these two were independent risk factors.2 Interestingly, by the time the beverage reaches more posterior tissues such as the oesophagus, the intensity of the heat of the beverage is conceivably lower. The fact that hot maté is a potential carcinogen for distal tissues as well as oral tissues may point to other carcinogenic mechanisms. Maté contains potential carcinogens such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) including benzo[a]pyrene, a well-known carcinogen found in cigarette smoke. It is likely that PAHs are introduced to maté during the industrial processing of the leaves. The levels of PAHs were shown to be high in both hot and cold maté infusions,11 and the mechanistic pathway by which PAHs can lead to oral cancers is more firmly established than that described by the thermal injury hypothesis.

The carcinogenic effects of maté are likely to extend beyond thermal injury and chemical content. This review as well as other studies has shown significant synergy between cigarette smoking and maté drinking. Carcinogenic constituents in maté appear to interact with carcinogens in cigarettes, and this may also be true in relation to alcohol. Nonetheless, the interaction between maté drinking and alcohol consumption requires further investigation, owing to the limited evidence base currently available. There is also some evidence to suggest a dose-response relationship between maté drinking and cancer risk, an unsurprising association with implications to certain populations. In Latin America and the Middle East, maté is often drunk out of a gourd or a vessel with an approximate content of 50 grams of dried leaves and stemlets, which can be steeped multiple times in hot or cold water. This content is particularly high when compared to a potentially harmless tea bag serving typically weighing only two grams.

Public health implications

Considering the substantial consumption of maté in certain populations and its increasing use in many countries (due to its perceived health benefits), more studies are needed before a definitive statement can be made regarding cancer risk associated with maté drinking. Future research should include population-based studies, focus on precisely measuring volume and temperature of maté intake and collect data on consumption of tobacco, alcohol, other hot drinks, fruit and vegetables.

References

Szymanska K, Matos E, Hung RJ, et al. Drinking of maté and the risk of cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract in Latin America: a case-control study. Cancer Causes Control 2010; 21: 1799–1806.

Islami F, Boffetta P, Ren JS, Pedoeim L, Khatib D, Kamangar F . High-temperature beverages and foods and oesophageal cancer risk – a systematic review. Int J Cancer 2009; 125: 491–524.

Loria D, Barrios E, Zanetti R . Cancer and yerba maté consumption: a review of possible associations. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2009; 25: 530–539.

Puangpraphant S, Berhow MA, Vermillion K, Potts G, Gonzalez de Mejia E . Dicaffeoylquinic acids in Yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis St. Hilaire) inhibit NF-κB nucleus translocation in macrophages and induce apoptosis by activating caspases -8 and -3 in human colon cancer cells. Mol Nutr Food Res 2011; 55: 1509–1522.

Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from: www.cochrane-handbook.org

Stefani ED, Moore M, Aune D, et al. Maté consumption and risk of cancer: a multi-site case-control study in Uruguay. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2011; 12: 1089–1093.

De Stefani E, Correa P, Oreggia F, et al. Black tobacco, wine and maté in oropharyngeal cancer. A case-control study from Uruguay. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 1988; 36: 389–394.

Oreggia F, De Stefani E, Correa P, Fierro L . Risk factors for cancer of the tongue in Uruguay. Cancer 1991; 67: 180–183.

Franco EL, Kowalski LP, Oliveira BV, et al. Risk factors for oral cancer in Brazil: a case–control study. Int J Cancer 1989; 43: 992–1000.

Pintos J, Franco EL, Oliveira BV, Kowalski LP, Curado MP, Dewar R . Maté, coffee, and tea consumption and risk of cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract in southern Brazil. Epidemiology 1994; 5: 583–590.

Kamangar F, Schantz MM, Abnet CC, Fagundes RB, Dawsey SM . High levels of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in maté drinks. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008; 17: 1262–1268.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Saman Warnakulasuriya, Department of Oral Medicine, King's College London, WHO Collaborating Centre for Oral Cancer, Denmark Hill Campus, London SE5 9RW, UK. E-mail: s.warne@kcl.ac.uk

Dasanayake AP, Silverman AJ, Warnakulasuriya S. Maté drinking and oral and oro-pharyngeal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol 2010; 46: 82–86.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Dakkak, I., Ternouth, A. Maté intake and risk of oral and pharyngeal cancers. Evid Based Dent 13, 18–19 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400842

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400842