Abstract

Data sources

MEDLINE, EMBASE and ISI the Web of Science

Study selection

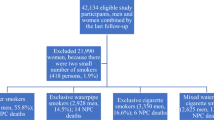

Articles in any language that assessed the association between water pipe smoking and any health outcome. Included studies were cohort, case-control and cross-sectional. Studies were excluded if they looked at physiological outcomes, non-tobacco pipe use, or didn't differentiate between this and other smoking habits.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were abstracted independently by two reviewers using a standardised screening guide and GRADE used to evaluate study quality. The I2 statistic was used to measure heterogeneity. Odds ratios for the effect of pipe smoking on lung, bladder, oesophageal and nasopharyngeal cancer, oral dysplasia, pregnancy outcomes, periodontal disease, hepatitis, respiratory illness and infertility were extracted.

Results

Twenty-three studies were included. Based on the available evidence, waterpipe tobacco smoking was significantly associated with lung cancer, respiratory illness, low birth-weight and periodontal disease. It was not significantly associated with bladder, nasopharyngeal and oesophageal cancers, neither with oral dysplasia or infertility, but the confidence Intervals (CIs) did not exclude important associations. Smoking a waterpipe in groups was not significantly associated with hepatitis C infection. The overall quality of evidence varied from very low to low.

Conclusions

The evidence from very low to low quality studies is that waterpipe tobacco smoking is possibly associated with a number of deleterious health outcomes including lung cancer, respiratory illness, low birth-weight and periodontal disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

There is a wide variety of smoking tobacco products on the world market to chose from, including cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos, bidis, chuttas and kreteks. Much is written on these smoking habits, their harm and the deleterious effects of smoked tobacco on human health. Waterpipe tobacco smoking (WPS) is a common practice in Eastern Mediterranean countries, the Middle East and parts of Asia, bound by cultural tradition of some populations. This method of smoking tobacco is gaining popularity in many parts of the Western world. The combination of flavouring agents and the paraphernalia itself used in the smoking process, along with its mystic appeal, novelty, affordability and the social atmosphere in which smoking often occurs, has made WPS attractive to women as well as men, cigarette smokers and nonsmokers alike, and particular groups, including persons of college age and younger adolescents.1 WPS typically consists of a combination of tobacco (often flavoured with honey or molasses and dried fruit), water and wood charcoal, and the waterpipe used for smoking is referred to as a hookah but also called hubble-bubble, arghileh, nargile, sheesha/shisha. Waterpipes involve the passage of smoke through water prior to inhalation.

WPS is emerging as an epidemic among young people. There has been a concerted effort in the public opinion and in the lay literature to portray WPS as a safe way of using tobacco. Social research has shown that over 70% of current waterpipe users believed that a hookah is less harmful than cigarettes. Although users report that they perceive a hookah to be less harmful than cigarettes, carbon monoxide(CO) levels are higher for patrons of hookah cafes, for both current and non-cigarette smokers. Exposure to second-hand smoke is also considerable. The greater CO exposure for hookah users compared with traditional bar users that was observed in one study is not consistent with peoples' perception.2 There is no safe way to use tobacco. In the case of WPS, the problems are even more complex, particularly because of the much longer duration of a session. WPS has been declared a public health problem by the World Health Organization.3

Much research has been focused on the role played by cigarette smoking and cancer. The carcinogens found in cigarette smoke have been evaluated by the IARC.4 The focus of research on carcinogens in tobacco and tobacco smoke has predominantly been on benzo-[a]pyrene, tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines (TSNA), especially N′-nitrosonornicotine (NNN) and 4-(N-nitrosomethylamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and aromatic amines, because of their established carcinogenic potency. Eleven compounds (2-naphthylamine, 4-aminobiphenyl, benzene, vinyl chloride, ethylene oxide, arsenic, beryllium, nickel compounds, chromium, cadmium and polonium-210) classified as IARC Group 1 human carcinogens have been reported as present in mainstream cigarette smoke. The compounds listed here are those primarily responsible for the cancer-causing effects of tobacco smoke. To date little research is available to similarly evaluate the carcinogenicity of compounds in WPS; a critique on standardising smoking machines to WPS (or lack of it) has been published.5

Despite lack of laboratory data the evidence of the adverse health effects of WPS is growing. A previous systematic review and meta-analysis6 based on six cross-sectional studies concluded WPS negatively affects lung function and may be as harmful as cigarette smoking. WPS, therefore, is likely to be a cause of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

A more recent systematic review by the same group was on all health outcomes.7 The 24 included studies were selected on the basis of standardised criteria after review of over 1,600 published works on WPS. WPS was found to be significantly affected with lung cancer, respiratory illness, low birth weight and periodontal disease. The strongest evidence suggesting hookah smoking was associated with a significantly higher risk for lung cancer emerged in a Kashmiri population, with about six fold elevated risk as compared to non-smoking controls.8

Examining all reported studies selected for the latest systematic review it is clear that no studies have been conducted on effects of WPS on oral or oropharyngeal cancer. One study on oral epithelial dysplasia was included but unfortunately the data were confounded by quat chewing, a popular habit in Yemen. As all dysplastic lesions were found on the quid chewing side the confounding effect of other agents in this study is clear.

The systematic review included four studies on periodontal health that examined associations of WPS with plaque and gingival indices, periodontal bone height loss and probing pocket depth. All four studies (reported individually) were based on the same cohort of patients that included 244 cases and 355 volunteers from Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. A significant association was found with plaque and gingival indices (no effect estimates were given), with bone loss (defined as bone loss <70%) OR of 3.5 (95% CI 1.6-7.6) among water pipe only smokers vs non smokers, OR rising to 7.5 (95% CI 3.0-18.3) among heavy users, with pocket depth (>10 sites with a probing depth >5mm) OR of 5.1(95% CI 2.0-13.5) for WPS.

One further study included in the systematic review had examined the effects of WPS on dry socket – that often has been independently associated with tobacco smoking. One hundred Egyptian males were included, who were found to have three times the risk of non smokers for developing a dry socket following extraction of a mesio-angular impacted wisdom tooth.

No data have emerged to estimate the risk of oral cancer in WPS users. Despite lack of data Rastan et al. 9 hypothesised that oral keratinocytes are susceptible to WPS.

Carcinogen uptake in humans exposed to tobacco smoke can be monitored by measurement of NNK metabolites that are specific to tobacco exposure10 and this may be a possible avenue to consider for further research when considering biomarkers of human carcinogen uptake among WPS.

There is a need for further high quality trials, particularly to examine the risk of oral cancer in WPS users. The current evidence on WPS as assimilated in the systematic review on other health issues is more than adequate to label it as a significant health hazard, most likely on a par with cigarette smoking.

References

Martinasek MP, McDermott RJ, Martini L . Waterpipe (hookah) tobacco smoking among youth. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2011; 41: 34–57.

Barnett TE, Curbow BA, Soule Jr EK, Tomar SL, Dennis L, Thombs DL . Carbon monoxide levels among patrons of hookah cafes. Am J Prev Med 2011; 40: 324–328.

World Health Organization. WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation (TobReg). Advisory Note: Waterpipe tobacco smoking: Health Effects, Research Needs and Recommended Actions by Regulators. pp 1–20. Switzerland: WHO Press Geneva, 2005.

IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking. Volume 83, 2004. Lyon: IARC

Chaouachi K, Sajid KM . A critique of recent hypothesis on oral (and lung) cancer induced by water pipe (hookah, shisa, narghile) tobacco smoking. Med Hypotheses 2010; 74: 843–846.

Raad D, Gaddam S, Schunemann HJ, et al. Effects of waterpipe smoking and lung function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest 2011; 139: 764–774.

Akl EA, Gaddam S, Gunukula SK, Honeine R, Jaoude PA, Irani J . The effects of waterpipe tobacco smoking on health outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Epidemiol 2010; 39: 834–857.

Koul PA, Hajni MR, Sheikh MA, et al. Hookah smoking and lung cancer in the kashmir valley of the Indian subcontinent. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011; 12: 519–524.

Rastam S, Li FM, Fouad FM, Al Kamal HM, Akil N, Al Moustafa AE . Water pipe smoking and human oral cancers. Med Hypotheses 2010; 74: 457–459.

Hecht SS . Tobacco carcinogens, their biomarkers and tobacco-induced cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2003; 3: 733–744.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Elie A Akl, Department of Medicine, State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14215, USA. E-mail: elieakl@buffalo.edu

Akl EA, Gaddam S, Gunukula SK, Honeine R, Jaoude PA, Irani J. The effects of waterpipe tobacco smoking on health outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Epidemiol 2010; 39: 834–857

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Warnakulasuriya, S. Waterpipe smoking, oral cancer and other oral health effects. Evid Based Dent 12, 44–45 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400790

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400790

This article is cited by

-

Hookah use patterns, social influence and associated other substance use among a sample of New York City public university students

Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy (2020)

-

Bioaerosols in the waterpipe cafés: genera, levels, and factors influencing their concentrations

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2019)