Abstract

Design

This was a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Intervention

One tablet was taken each day before sleep for 6 months. The test group received sublingual vitamin B12 tablets (1000 mcg of vitamin B12) whereas the control group took a placebo of the same shape, size, colour and flavour. Participants met with staff monthly.

Outcome measure

Duration (days) of an aphthous stomatitis episode, monthly number of aphthous ulcers, and severity of pain according to the Numerous Rating Scale (NRS), were recorded in a diary.

Results

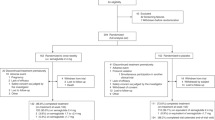

Fifty-eight people suffering from recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) participated: 31 were allocated to the intervention group and 27 to the control group. The duration of outbreaks, the number of ulcers, and the level of pain were reduced significantly (P <0.05) at 5 and 6 months of treatment with vitamin B12, regardless of initial vitamin B12 levels in the blood. During the last month of treatment a significant number of participants in the intervention group reached “no aphthous ulcers status” (74.1% vs 32.0%; P <0.01).

Conclusions

Vitamin B12 treatment, which is simple, inexpensive and low-risk, seems to be effective for patients suffering from RAS, regardless of the serum vitamin B12 level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

The possible association between recurrent aphthous ulceration (RAU) and vitamin B12 deficiency was first suggested more than 55 years ago.1 Despite being unsubstantiated because of a lack of robust evidence, it is widely recognised as a possible predisposing factor for RAU. The few available controlled studies analysing haematological status in RAU patients give controversial results, some supporting a link2, 3 whereas others refute a connection.4, 5 Similarly, reports on supplemental treatments are scarce and almost entirely based on studies of doubtful quality that are small in size, uncontrolled, not randomised and unmasked.6, 7, 8

The present study therefore represents an important advance in this field as it the first randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on vitamin B12 supplementation in more than half a century. There are, however, a number of subtle yet important problems with it. Firstly, the diagnostic criteria did not consider recurrent intraoral herpetic ulceration, the main differential diagnosis of RAU. Older studies suggested the use of high-dose vitamin B12 in the treatment of herpetic stomatitis, and therefore its absence from the diagnostic criteria is all the more striking.9 In addition, the vague reporting of clinical details as a possible source of bias does not appear to have been considered. It is unclear whether aphthous ulceration included in the test and control groups was limited to minor RAU or incorporated other varieties. This may be partially explained by the lack of dentists and dermatologists involved in the study.

The authors are also unclear about concealment of allocation sequences, despite assurances that blinding of both physicians and participants occurred until the end of the study. Although patient age, gender and origin were apparently well-matched, educational standard was incompatible between the two groups, with two thirds of the intervention group being highly educated but less than half of the control group fitting this category. There is evidence to suggest a relationship between low income and education, and increased duration and intensity of pain in comparison with higher income/ educational groups.10 Thus, these differences, although not statistically significant, may have introduced another source of bias. Moreover, no intention to treat analysis was applied, thus an over-optimistic estimate of the efficacy of this intervention is likely because of all the above remarks.

Finally, there is a lack of any consistent biological explanation for the benefits observed, with the authors still suggesting an unrecognised function of vitamin B12. In addition, alternative hypotheses such as Helicobacter pylori involvement, a proposed putative aetiological factor of RAU also causing vitamin B12 deficiency11, 12 were not considered.

Regardless of all the criticisms levied, the most outstanding finding of this study is that 74% of individuals in the intervention group were free of ulceration after a 6-month period compared with 32% in the control group. This alone warrants further investigation, through larger and more highly controlled trials, to confirm the effectiveness of vitamin B12 in the treatment of RAU.

References

Brachmann F . Treatment of chronically recurrent aphthae with vitamin B12. Zahnarztl Welt 1954 9: 58–59.

Burgan SZ, Sawair FA, Amarin ZO . Hematologic status in patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis in Jordan. Saudi Med J 2006; 27: 381–384.

Koybasi S, Parlak AH, Serin E, Yilmaz F, Serin D . Recurrent aphthous stomatitis: investigation of possible etiologic factors. Am J Otolaryngol 2006; 27: 229–232.

Olson JA, Feinberg I, Silverman Jr S, Abrams D, Greenspan JS . Serum vitamin B12, folate, and iron levels in recurrent aphthous ulceration. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1982; 54: 517–520.

Thongprasom K, Youngnak P, Aneksuk V . Hematologic abnormalities in recurrent oral ulceration. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Publ Health 2002; 33: 872–877.

Wray D, Ferguson MM, Mason DK, Hutcheon AW, Dagg JH . Recurrent aphthae: treatment with vitamin B12, folic acid, and iron. Br Med J 1975; 2: 490–493.

Porter S, Flint S, Scully C, Keith O . Recurrent aphthous stomatitis: the efficacy of replacement therapy in patients with underlying hematinic deficiencies. Ann Dent 1992; 51: 14–16.

Gulcan E, Toker S, Hatipoglu H, Gulcan A, Toker A . Cyanocobalamin may be beneficial in the treatment of recurrent aphthous ulcers even when vitamin B12 levels are normal. Am J Med Sci 2008; 336: 379–382.

Abelin M . Treatment of herpes simplex with shock doses of vitamin B12 (Cycobemin) and Iloban. Sven Lakartidn 1961; 58: 1984–1990.

Krueger AB, Stone AA . Assessment of pain: a community-based diary survey in the USA. Lancet 2008; 371: 1519–1525.

Kaptan K, Beyan C, Ural AU, et al. Helicobacter pylori — is it a novel causative agent in Vitamin B12 deficiency? Arch Intern Med 2000; 160: 1349–1353.

Karaca S, Seyhan M, Senol M, Harputluoglu MM, Ozcan A . The effect of gastric Helicobacter pylori eradication on recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Int J Dermatol 2008; 47: 615–617.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Ilia Volkov, Lea Imenu Street 59/2, Beer-Sheva, 84514, Israel. E-mail: r0019@zahav.net.il

Volkov I, Rudoy I, Freud T, et al. Effectiveness of vitamin B12 in treating recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Board Fam Med 2009; 22: 9–16

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carrozzo, M. Vitamin B12 for the treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Evid Based Dent 10, 114–115 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400688

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400688