Abstract

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common type of birth defect, and the etiology of most cases is unknown. CHD often occurs in association with other birth malformations, and only in a minority are disease-causing chromosomal abnormalities identified. We hypothesized that children with CHD and additional birth malformations have cryptic chromosomal abnormalities that might be uncovered using recently developed DNA microarray-based methodologies. We recruited 20 children with diverse forms of CHD and additional birth defects who had no chromosomal abnormality identified by conventional cytogenetic testing. Using whole-genome array comparative genomic hybridization, we screened this population, along with a matched control population with isolated heart defects, for chromosomal copy number variations. We discovered disease-causing cryptic chromosomal abnormalities in five children with CHD and additional birth defects versus none with isolated CHD. The chromosomal abnormalities included three unbalanced translocations, one interstitial duplication, and one interstitial deletion. The genetic abnormalities were predominantly identified in children with CHD and a neurologic abnormality. Our results suggest that a significant percentage of children with CHD and neurologic abnormalities harbor subtle chromosomal abnormalities. We propose that children who meet these two criteria should receive more extensive genetic testing to detect potential cryptic chromosomal abnormalities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Cardiovascular malformations are the most common type of birth defect and result in significant mortality worldwide. They have an estimated incidence of eight per 1000 live births and affect an estimated 10% of spontaneous miscarriages (1). Recent advances in medical and surgical management have resulted in 85% of affected children surviving to adulthood; as a result, there are an estimated 1,000,000 adults with congenital heart disease (CHD) in the United States alone, with similar numbers in Europe (2,3). The reported incidence of CHD has not changed over the past several decades, and the etiology for most cases of CHD is proposed to be multifactorial.

Genetic influences have long been implicated as the etiology for a subset of CHD. Common, cardiac malformations occur in the setting of multiple birth defects as part of a well-defined syndrome associated with chromosomal aberrations. Classic examples include children with Down syndrome (trisomy 21) or Turner syndrome (monosomy X) who have an increased incidence of CHD. Early epidemiologic studies reported that 8% of CHD was due to chromosomal or single-gene defects whereas the majority (>90%) was multifactorial (4). Although the majority of CHD is termed “nonsyndromic,” an estimated 25–40% of patients with CHD have other birth anomalies (5). Over the past decade, specific genes that cause syndromic CHD have been discovered, and more recently, a few genetic etiologies of nonsyndromic CHD have been elucidated (6–8). However, most children with CHD, including those with other birth defects, have no obvious genetic abnormality.

Since its advent in the late 1950s, chromosomal analysis by karyotype has been the standard method used in the genetic evaluation of children with multiple anomalies (9). One limitation of conventional cytogenetic evaluation is that small chromosomal abnormalities may be missed. The generally accepted minimum limit of detection with this method is about 5–10 Mb. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is a dramatically more sensitive cytogenetic technique to detect small copy number changes (i.e. deletions or duplications) and gene rearrangements but is not practical to apply on a genome-wide level. Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) is a relatively new methodology that can be used to identify submicroscopic chromosomal copy number changes genome-wide (10–12). This technique has developed into a powerful way to efficiently interrogate the whole genome for subtle abnormalities. It has also led to the discovery of numerous pathologic small copy number changes, predominantly in patients with specific birth anomalies or neurologic diseases such as learning disabilities and autism (13–15).

The purpose of this study was to determine whether subtle chromosomal anomalies previously undetected by conventional cytogenetic banding methods could be identified by array CGH in children with CHD. We hypothesized that children with CHD and additional birth defects are more likely to harbor these chromosomal abnormalities than children with isolated CHD. Analysis of 40 children with CHD revealed five children with previously unidentified chromosomal abnormalities. The genetic abnormalities, which included three unbalanced translocations, one chromosomal deletion and one chromosomal duplication, were found only in the population of 20 subjects who had additional birth anomalies along with CHD. No obvious disease-causing chromosomal copy number changes were identified in the population with isolated CHD. Although we did identify three novel chromosomal copy number changes in this isolated CHD population, all were present at either low frequency in ethnically matched control populations or in the clinically unaffected parents. These findings highlight the need for high-resolution genetic screening in children with CHD and additional birth defects, even if they have had a normal karyotype. Our results indicate that a significant fraction of these children harbor cryptic pathologic chromosomal abnormalities.

METHODS

Subjects.

The subject population was comprised of 40 unrelated individuals (21 males, 19 females) with CHD. From January to December 2006, subjects were prospectively recruited for genetic testing and informed consent obtained according to protocol as approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Twenty subjects with CHD had additional diagnoses and are listed in Table 1 (population A). The types of CHD varied and included: 4 subjects with tetralogy of Fallot; 4 with ostium secundum atrial septal defects; 1 with a sinus venosus atrial septal defect; 2 with atrioventricular septal defect; 1 with a perimembranous ventricular septal defect; 2 with pulmonic valve stenosis; 2 with hypoplastic left heart syndrome; 1 with aortic coarctation and bicuspid aortic valve; 1 with dysplastic mitral valve; 1 with patent ductus arteriosus; and 1 with double outlet right ventricle. The individuals included 10 male and 10 females and were of variable ethnicity specifically 12 European-Americans, 7 Hispanics, and 1 Asian. A control population (population B, Supplementary Table 1, available online at http://www.pedresearch.com) was randomly selected from our database of individuals enrolled in an ongoing program at Children's Medical Center Dallas. These subjects were matched to population A according to the type of heart defect, but had no other known anomalies. This control population was comprised of 11 males and 9 females and included 11 European Americans, 8 Hispanics, and 1 Asian. All subjects with CHD and additional anomalies had previous genetic testing including a karyotype that was interpreted as normal by conventional cytogenetic G-banding methodology. All subjects underwent complete cardiac evaluation at Children's Medical Center Dallas and echocardiogram, cardiac catheterization and operative reports were reviewed when available. In addition, the entire medical record was retrospectively reviewed to identify the presence of additional diagnoses. Because the clinical assessment of additional anomalies was performed in a retrospective manner, all patients were neither examined by the same geneticist/neurologist nor had medical testing that was not part of routine medical care. Developmental assessments were used only if evaluation was performed in subjects after 18 mo of age. Venous blood samples were collected and genomic DNA isolated using the PUREGENE kit (Gentra Systems) from recruited subjects.

Array comparative genomic hybridization.

Genomic DNA was submitted to Nimblegen Systems (Madison, WI) for high-resolution whole genome CGH analysis. Each array contained 385,000 isothermal 50- to 75-bp oligonucleotide probes spanning the entire nonrepetitive human genome with a median spacing of 6270 bp. Pooled normal male DNA (Promega G1471) was used as a reference sample for hybridizations. Array data were analyzed for copy number changes by Nimblegen using a circular binary segmentation algorithm with unaveraged probe signal intensities as well as probes averaged over 60 kb, 120 kb, and 300 kb windows (16). Relative intensity of the sample versus reference signals was reported on a log2 scale, so that a normal copy number (relative intensity = 1) should give a value of log2 (1) = 0. Heterozygous duplications theoretically should give a value of log2(3/2) = +0.58 and heterozygous deletions a ratio of log2(1/2) = −1.0, but the actual magnitude of the ratio observed is somewhat less due to background hybridization. Inspection of array data from other studies revealed that the vast majority of signals with log2 ratios in the range of −0.3 to + 0.3 are either technical artifacts or represent genomic regions that show variable copy numbers among normal individuals (Database of Genomic Variants); therefore, only signals with log2 ratio >+0.3 or <−0.3 were considered to denote potential causal variations.

FISH and quantitative PCR.

Chromosomal copy number abnormalities detected by array CGH were confirmed by FISH. Peripheral blood samples were collected from probands and their available parents and FISH was performed on lymphocyte metaphase preparations using probes specific for the reported abnormalities. These included commercially available 1q, 7q, 15q, 16q, 17q, and 19p subtelomeric probes (Vysis, Inc.), a commercially available 22q11.2 probe (TUPLE1, Vysis, Inc.), and custom 2q BAC clone probes, RP11-91M5 and RP11-81P3 (BACPAC Resources, Inc.).

For six putative copy number changes too small to detect by FISH, real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT qPCR) was performed using custom Taqman probes and a reference RNAseP genomic probe (sequences available upon request). RT qPCR was performed using an ABI instrument and Taqman Universal PCR Master Mix kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using DNA from probands, parent(s) (if available), and unrelated ethnically-matched control individuals. 10–30 ng of genomic DNA was used for each RT PCR reaction. Experiments were performed in triplicate and mean ratios of regions of interest, normalized to RNAseP, were calculated for probands, parent(s) (if available), and unrelated normal controls. Proband/control ratios >1.3 or <0.7 were considered evidence of duplication or deletion, respectively.

Statistical analysis.

Bivariate analysis was performed using Fisher's Exact test (two-tailed) for associations between categorical variables and t test to compare means of continuous variables in the analysis of copy number variations (CNV) between populations. p Values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Twenty subjects with CHD and additional birth anomalies (population A) and twenty subjects with isolated CHD (population B) were screened for chromosomal anomalies by high-resolution oligonucleotide array CGH. We identified 296 CNV in the entire population of 40 individuals with CHD. A similar number of CNV were identified in each of the populations (A: 161 CNV = 8.1 ± 3.2 CNV/subject, B: 135 CNV = 6.8 ± 2.9 CNV/subject; p value = NS). The majority (254/296 = 86%) of the identified CNV had been previously detected in normal individuals and reported in the Database of Genomic Variants (http://projects.tcag.ca/variation/) and therefore likely represent copy number polymorphisms. An additional 9.8% (29/296) of the duplications resided within chromosomal regions known to harbor segmental duplications or in regions containing no known or hypothetical genes and were not investigated further (Supplementary Table 2, available online athttp://www.pedresearch.com).

The remaining thirteen CNV were analyzed to determine whether they represent chromosomal abnormalities that may be associated with CHD. Seven large CNVs were identified in five subjects. In three subjects (A9, A10, and A20), we identified 5 CNVs that were due to cryptic unbalanced chromosomal translocations (Fig. 1B, C, E and Table 2) (17). Genetic testing of the parents of subject A10 identified a balanced reciprocal translocation in one of the parents, whereas parental testing was not performed on subject A9 (Table 2). The mother of A20 was found to carry a balanced 7:17 translocation whereas the father had a normal karyotype. Close inspection of the unaveraged array CGH data from subject A20 led to the identification of a small 75 kb CNV on the distal long arm of chromosome 7 (Fig. 1E). An interstitial chromosomal duplication and interstitial deletion were discovered in subjects A8 and A11, respectively (Table 2 and Fig. 1A and D). Maternal testing of patient A8 was normal (father was not available for testing) whereas the parents of A11 had a normal karyotype with no evidence of 22q11.2 deletion. FISH studies confirmed the presence of all seven large CNVs except for the microdeletion of distal chromosome 7q, which may be too small for the commercial 7q probe to detect (Fig. 2). In the three patients where DNA was available from both parents, we were able to demonstrate that two unbalanced translocations were the result of inheritance from a parent harboring a previously unrecognized balanced translocation, whereas the deletion in A11 was a de novo occurrence.

Copy number variations discovered by array CGH. A, In subject A8, a 6.6 Mb duplication of chromosome (ch) 2q.33 was found. B, A 2 Mb duplication of ch16q and 600 kb deletion of ch19p was identified in subject A9. C, A 12.3 Mb deletion of ch1q and 8.1 Mb duplication of ch15q was discovered in subject A10. D, In subject A11, a 3Mb deletion of chromosome 22q11 is identified. E, In subject A20, a 75 kb deletion of ch7q and 14.1 Mb duplication of ch17q was identified. The respective chromosomes are shown and labeled. Signal intensity is plotted on a log2 scale, so that a normal copy number gives a value of 0. Chromosome deletions are denoted by leftward segments (green) whereas duplicated segments are rightward (red).

FISH demonstrates chromosomal abnormalities in five subjects with CHD and additional anomalies. A, Interstitial duplication of long arm of chromosome (ch) 2. FISH using custom BAC clones shows normal hybridization signals to the normal homologue of ch2 (arrowhead) and duplicated hybridization signals to the abnormal homologue of ch2 (arrow). Hybridization signals are also seen in interphase cells (right) with long arrows showing two signals (duplication) and arrowhead showing a single signal (normal). B, Unbalanced translocation involving the long arm of chromosome 16 and short arm of ch19. B1, FISH using subtelomeric probes to the short arm (green signal) and long arm of ch16 (red signal) indicate trisomy for the terminal region of ch16. B2, FISH using probes for the subtelomeres of the short arm (green), long arm (red), and centromere (aqua) of ch19. Absence of the green signal (arrowhead) indicative of deletion of the distal segment of the short arm of ch19 when compared with normal ch19 (arrow). C, Unbalanced translocation involving the long arm of ch1 and the long arm of ch15. C1, FISH using subtelomeric sequences for the short arm (green) and the long arm (red) of chromosome 1. Arrow identifies the distal long arm of the abnormal chromosome 1 (signal missing), arrowhead identifies the distal long arm of the normal chromosome 1. Additional signals (yellow) in C1 identify Xp/Yp subtelomeric regions used as reporter sequences. C2, Arrows identify hybridization signals for the subtelomeric sequences of ch15. Arrowhead indicates a ch15q hybridization signal on the long arm of ch1. Additional signals in C2 indicate short arm of ch10 (green) and long arm of 10 (red) as reporter sequences. D, FISH showing normal hybridization to the DiGeorge/velo-cardio-facial syndrome critical region at chromosome 22q11.2 using a TUPLE1 probe. Arrowhead identifies normal hybridization pattern (red), arrow points to the deleted region. Green signal identifies distal ch22q, a reporter sequence encoding the arylsulfatase A gene. E, Unbalanced translocation involving the long arm of ch7 and the long arm of ch17. E1, FISH showing hybridization of subtelomeric sequences to the short arm (red) and the long arm (green) of ch7. Arrows indicate hybridization to the long arms of both the normal and abnormal homologues of ch7 indicating that the subtelomeric sequences on the abnormal chromosome are intact. The second set of signals is a reporter and identifies ch14. E2, Arrowhead identifies hybridization to the telomeres of the long arms of the normal homologues of ch17. Arrow identifies a ch17 hybridization signal on the distal long arm of ch7. The scale bar in A represents 5 um and the same magnification of 600× is used in all images.

For the remaining six CNV, RT qPCR was used to confirm the genetic abnormality. RT qPCR confirmed microdeletions of chromosome 7 (∼120,000 bp) and chromosome 13 (∼180,000 bp) and one microduplication of chromosome 3 (∼60,000 bp) whereas three CNVs were not corroborated suggesting that they are false positives (Supplementary Fig. 1, available online at http://www.pedresearch.com). The microdeletions of chromosome 7 and 13 were not detected in a control population of 200 ethnically matched chromosomes. However, we did find that both microdeletions were inherited from an unaffected parent who had a normal transthoracic echocardiogram (Supplementary Fig. 1, available online at http://www.pedresearch.com). DNA was unable to be obtained from the parents of the proband with the microduplication of chromosome 3 but a similar duplication was identified by RT qPCR in 1/200 ethnically matched control chromosomes (Supplementary Fig. 1, available online at http://www.pedresearch.com).

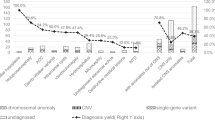

Analysis of our data demonstrated that certain populations with CHD are at higher risk for chromosomal abnormalities (Table 3). Chromosomal abnormalities were more likely to be present in individuals with CHD and additional birth anomalies when compared with isolated CHD (5/20 versus 0/20, p < 0.05). The presence of a neurologic abnormality, defined as either developmental delay or a structural malformation, in association with CHD resulted in even greater probability of a chromosomal abnormality when compared with other types of birth defects or isolated CHD (5/11 versus 0/9, p value <0.04; 5/11 versus 0/20, p value <0.005). In the population studied, children with cardiac and neurologic abnormalities had a higher incidence of chromosomal abnormalities than has been recognized by current cytogenetic banding methodology.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that 25% of children with CHD and additional malformations had abnormal copy number changes that could not be seen at the level of G-banded karyotype alone. However, these abnormalities were detectable by whole genome array CGH. In patients with CHD and neurologic abnormalities, the incidence of small deletions, duplications, and translocations was even higher, approaching 50% (Table 3). The control population with isolated CHD had no obvious disease-causing copy number changes detectable by array CGH, although we cannot rule out the presence of very small CNVs. We also cannot exclude mosaic abnormalities, which may result in CGH signals below our threshold (log2 ratio >0.3 or <−0.3). Although our analysis was limited by a small and heterogenous study population, our findings suggest that a subset of patients with CHD, especially those with neurologic abnormalities, have a high incidence of chromosomal anomalies that may be missed by conventional karyotyping.

The chromosomal copy number changes found in this study affected relatively large regions of DNA that spanned numerous genes and in three out of five cases were demonstrated to be de novo. The unbalanced translocations found in patients A9, A10, and A20 are the likely explanations for their disease phenotype (18). These chromosomal abnormalities involve both the deletion and duplication of numerous genes, thereby precluding discovery of candidate CHD-disease genes within the affected regions exhibiting copy number changes. Duplications of chromosome 2q33 and deletions of 22q11.2 have been reported in the literature to be associated with birth malformations (19–21). Although myelomeningocele is not a typical manifestation of the 22q11 deletion syndrome in humans or in the equivalent mouse model, case reports of patients with tetralogy of Fallot and neural tube defects have been described (22,23). We did identify small CNV in 7.5% of the subjects (3/40) with CHD. The presence of these 3 CNV in unaffected parents or normal control individuals along with the affected subjects suggest that they cannot independently cause CHD with complete penetrance, but we cannot rule out the possibility that they function as susceptibility loci. In addition, the significance of the 21 novel CNV involving regions containing no predicted genes is unclear and demonstrates the need for larger public databases on normal CNV.

Previous studies have determined that single gene defects and chromosomal abnormalities are responsible for only 10–15% of CHD, whereas the majority of CHD is thought to be due to the interaction of complex environmental and genetic factors (24). Our data along with a recent report by Thienpont et al. (25) suggest that the use of array CGH will result in the identification of an increasing number of chromosomal abnormalities in individuals with CHD and additional birth defects. In our study, the population of children with CHD and associated neurologic abnormalities were at highest risk for these chromosomal anomalies. The data from our small control population suggests that children with isolated CHD are less likely to harbor chromosomal abnormalities that can be detected by this array CGH methodology but newer technologies may detect smaller disease-causing CNV in this population. This study provides further evidence that subtle chromosomal abnormalities in patients with CHD and other anomalies are being missed in current clinical practice.

Many of the CNVs identified in our population were localized to telomeric regions. In that regard, subtelomeric FISH analysis would have detected 60% (3/5) of the cryptic abnormalities found in this study. However, a single test, array CGH, detected all of the chromosomal copy number changes and simultaneously defined the chromosome breakpoints. In addition, high resolution oligonucleotide array CGH can detect complex subtelomeric rearrangements, such as the deletion of chromosome 7 in Subject A20, which may be missed by subtelomeric FISH panels that use single large clones to the most distal unique sequences (26).

The identification of genetic etiologies for CHD is important in providing more accurate genetic counseling for parents considering having other children. The recurrence risk for most CHD varies from 2 to 6% (27) but this risk is significantly increased when the parents are found to harbor balanced translocations or chromosomal duplications/deletions, which occurred in two of our participating families. Additionally, this information is important for patients with CHD as they reach adulthood and decide to start families. This increased knowledge will also allow for improvements in medical care and parental understanding about future expectations. As a corollary, the use of sensitive methods such as array CGH to stratify patients according to the presence of genetic abnormalities may be important when studying the long-term outcome of patients with CHD.

Array CGH has been used to discover disease-causing genes (28,29). The primary methodology that has been used to identify novel disease-causing genes for CHD has been linkage analysis, which requires the identification of large pedigrees spanning several generations with multiple affected family members. As such, most CHD with known genetic causes involves less severe cardiac malformations such as septal defects and valvular disease that can segregate in extended multi-generation pedigrees (30). As the use of array CGH becomes more commonplace, it will likely serve as an important tool for gene discovery in CHD, specifically in certain forms that typically resulted in neonatal lethality before the development of modern surgical techniques. This growth will lead to a plethora of CNV of uncertain significance identified by high-resolution array CGH and highlights the need for more extensive databases of array CGH findings in phenotypically well-characterized populations (31). To this end, array CGH data and associated phenotypes for disease-causing chromosomal abnormalities identified in this study have been deposited in DECIPHER (DatabasE of Chromosomal Imbalance and Phenotype in Humans using Ensembl Resources, http://decipher.sanger.ac.uk/).

This study demonstrates that children with CHD and other anomalies have a relatively high incidence of cryptic chromosomal abnormalities, which may not be detected by conventional karyotyping. This is especially true in patients with associated neurologic involvement. We would advocate the screening of patients with CHD and neurologic abnormalities such as developmental delay for chromosomal abnormalities using an array-based method or subtelomeric FISH, in addition to standard cytogenetic G-banding methods. As genome-wide array based methods become more widely available clinically, they will undoubtedly serve as an important tool in the evaluation of children with birth defects.

Abbreviations

- CGH:

-

comparative genome hybridization

- CHD:

-

congenital heart disease

- CNV:

-

copy number variation

- RT qPCR:

-

real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

References

Hoffman JI, Kaplan S 2002 The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 39: 1890–1900

Warnes CA, Liberthson R, Danielson GK, Dore A, Harris L, Hoffman JI, Somerville J, Williams RG, Webb GD 2001 Task force 1: the changing profile of congenital heart disease in adult life. J Am Coll Cardiol 37: 1170–1175

Gatzoulis MA 2004 Adult congenital heart disease: a cardiovascular area of growth in urgent need of additional resource allocation. Int J Cardiol 97: 1–2

Nora JJ 1993 Causes of congenital heart diseases: old and new modes, mechanisms, and models. Am Heart J 125: 1409–1419

Bernstein D 2004 Evaluation of the cardiovascular system. Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 17th ed. Philadelphia, Saunders pp 1481–1488

Gelb BD 2004 Genetic basis of congenital heart disease. Curr Opin Cardiol 19: 110–115

Goldmuntz E 2004 The genetic contribution to congenital heart disease. Pediatr Clin North Am 51: 1721–1737

Ransom J, Srivastava D 2007 The genetics of cardiac birth defects. Semin Cell Dev Biol 18: 132–139

Trask BJ 2002 Human cytogenetics: 46 chromosomes, 46 years and counting. Nat Rev Genet 3: 769–778

Kallioniemi A, Kallioniemi OP, Sudar D, Rutovitz D, Gray JW, Waldman F, Pinkel D 1992 Comparative genomic hybridization for molecular cytogenetic analysis of solid tumors. Science 258: 818–821

du Manoir S, Speicher MR, Joos S, Schrock E, Popp S, Dohner H, Kovacs G, Robert-Nicoud M, Lichter P, Cremer T 1993 Detection of complete and partial chromosome gains and losses by comparative genomic in situ hybridization. Hum Genet 90: 590–610

Pollex RL, Hegele RA 2007 Copy number variation in the human genome and its implications for cardiovascular disease. Circulation 115: 3130–3138

Shaw-Smith C, Redon R, Rickman L, Rio M, Willatt L, Fiegler H, Firth H, Sanlaville D, Winter R, Colleaux L, Bobrow M, Carter NP 2004 Microarray based comparative genomic hybridisation (array-CGH) detects submicroscopic chromosomal deletions and duplications in patients with learning disability/mental retardation and dysmorphic features. J Med Genet 41: 241–248

Menten B, Maas N, Thienpont B, Buysse K, Vandesompele J, Melotte C, de Ravel T, Van Vooren S, Balikova I, Backx L, Janssens S, De Paepe A, De Moor B, Moreau Y, Marynen P, Fryns JP, Mortier G, Devriendt K, Speleman F, Vermeesch JR 2006 Emerging patterns of cryptic chromosomal imbalance in patients with idiopathic mental retardation and multiple congenital anomalies: a new series of 140 patients and review of published reports. J Med Genet 43: 625–633

Sebat J, Lakshmi B, Malhotra D, Troge J, Lese-Martin C, Walsh T, Yamrom B, Yamrom B, Yoon S, Krasnitz A, Kendall J, Leotta A, Pai D, Zhang R, Lee YH, Hicks J, Spence SJ, Lee AT, Puura K, Lehtimaki I, Ledbetter D, Gregersen PK, Bregman J, Sutcliffe JS, Jobanputra V, Chung W, Warburton D, King MC, Skuse D, Geschwind DH, Gilliam TC, Ye K, Wigler M 2007 Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with autism. Science 316: 445–449

Venkatraman ES, Olshen AB 2007 A faster circular binary segmentation algorithm for the analysis of array CGH data. Bioinformatics 23: 657–663

Shaffer LG, Tommerup N 2005 ISCN: An International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature. Basel, S. Karger

Ravnan JB, Tepperberg P, Papenhausen P, Lamb AN, Hedrick J, Eash D, Ledbetter DH, Martin CL 2006 Subtelomere FISH analysis of 11688 cases: an evaluation of the frequency and pattern of subtelomere rearrangements in individuals with developmental disabilities. J Med Genet 43: 478–489

Bird LM, Mascarello JT 2001 Chromosome 2q duplications: case report of a de novo interstitial duplication and review of the literature. Am J Med Genet 100: 13–24

Sebold CD, Romie S, Szymanska J, Torres-Martinez W, Thurston V, Muesing C, Vance GH 2005 Partial trisomy 2q: report of a patient with dup (2)(q33.1q35). Am J Med Genet A 134: 80–83

Ryan AK, Goodship JA, Wilson DI, Philip N, Levy A, Seidel H, Schuffenhauer S, Oechsler H, Belohradsky B, Prieur M, Aurias A, Raymond FL, Clayton-Smith J, Hatchwell E, McKeown C, Beemer FA, Dallapiccola B, Novelli G, Hurst JA, Ignatius J, Green AJ, Winter RM, Brueton L, Brondum-Nielsen K, Scamber PJ 1997 Spectrum of clinical features associated with interstitial chromosome 22q11 deletions: a European collaborative study. J Med Genet 34: 798–804

Baldini A 2002 DiGeorge syndrome: the use of model organisms to dissect complex genetics. Hum Mol Genet 11: 2363–2369

Maclean K, Field MJ, Colley AS, Mowat DR, Sparrow DB, Dunwoodie SL, Kirk EP 2004 Kousseff syndrome: a causally heterogeneous disorder. Am J Med Genet A 124: 307–312

Ferencz C, Boughman JA, Neill CA, Brenner JI, Perry LW 1989 Congenital cardiovascular malformations: questions on inheritance. Baltimore-Washington Infant Study Group. J Am Coll Cardiol 14: 756–763

Thienpont B, Mertens L, de Ravel T, Eyskens B, Boshoff D, Maas N, Fryns JP, Gewillig M, Vermeesch JR, Devriendt K 2007 Submicroscopic chromosomal imbalances detected by array-CGH are a frequent cause of congenital heart defects in selected patients. Eur Heart J 28: 2778–2784

Ballif BC, Sulpizio SG, Lloyd RM, Minier SL, Theisen A, Bejjani BA, Shaffer LG 2007 The clinical utility of enhanced subtelomeric coverage in array CGH. Am J Med Genet A 143: 1850–1857

Nora JJ, Nora AH 1988 Familial risk of congenital heart defect. Am J Med Genet 29: 231–233

Vissers LE, Veltman JA, van Kessel AG, Brunner HG 2005 Identification of disease genes by whole genome CGH arrays. Hum Mol Genet 14: R215–R223

Sharp AJ, Hansen S, Selzer RR, Cheng Z, Regan R, Hurst JA, Stewart H, Price SM, Blair E, Hennekam RC, Fitzpatrick CA, Segraves R, Richmond TA, Guiver C, Albertson DG, Pinkel D, Eis PS, Schwartz S, Knight SJ, Eichler EE 2006 Discovery of previously unidentified genomic disorders from the duplication architecture of the human genome. Nat Genet 38: 1038–1042

Garg V 2006 Insights into the genetic basis of congenital heart disease. Cell Mol Life Sci 63: 1141–1148

Lee C, Iafrate AJ, Brothman AR 2007 Copy number variations and clinical cytogenetic diagnosis of constitutional disorders. Nat Genet 39: S48–S54

Acknowledgements

We thank the participating subjects and families; C. Rains for research coordinator support; T. Hyatt in the McDermott Center for Human Growth and Development, and G. Bartov in the UT Southwestern Cytogenetics Laboratory for technical assistance. Divisions of Cardiology and Cardiothoracic Surgery at Children's Medical Center Dallas for assistance with clinical information; and Drs. W. A. Scott and M. Maitra for critical review of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary material available online at http://www.pedresearch.com.

ArticlePlus

Click on the links below to access all the ArticlePlus for this article.

Please note that ArticlePlus files may launch a viewer application outside of your web browser. http://links.lww.com/PDR/A34

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Richards, A., Santos, L., Nichols, H. et al. Cryptic Chromosomal Abnormalities Identified in Children With Congenital Heart Disease. Pediatr Res 64, 358–363 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e31818095d0

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e31818095d0

This article is cited by

-

Copy number variant analysis for syndromic congenital heart disease in the Chinese population

Human Genomics (2022)

-

Estimating the frequency of causal genetic variants in foetuses with congenital heart defects: a Chinese cohort study

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2022)

-

Chromosomal microarray analysis in developmental delay and intellectual disability with comorbid conditions

BMC Medical Genomics (2018)

-

Identification of De Novo and Rare Inherited Copy Number Variants in Children with Syndromic Congenital Heart Defects

Pediatric Cardiology (2018)

-

Chromosome microarray analysis in the investigation of children with congenital heart disease

BMC Pediatrics (2017)