Abstract

Purpose: This study assesses primary care physicians' experience ordering and referring patients for genetic testing, and whether minority-serving physicians are less likely than those serving fewer minorities to offer such services.

Methods: Survey of a random sample of 2000 primary care physicians in the United States (n = 1120, 62.3% response rate based on eligible respondents) conducted in 2002 to assess what proportion have (1) ever ordered a genetic test in general or for select conditions; (2) ever referred a patient for genetic testing to a genetics center or counselor, a specialist, a clinical research trial, or to any site of care.

Results: Nationally, 60% of primary care physicians have ordered a genetic test and 74% have referred a patient for genetic testing. Approximately 62% of physicians have referred a patient for genetic testing to a genetics center/counselor or to a specialist, and 17% to a clinical trial. Minority-serving physicians were significantly less likely to have ever ordered a genetic test for breast cancer, colorectal cancer, or Huntington disease, or to have ever referred a patient for genetic testing relative to those serving fewer minorities.

Conclusions: Reduced utilization of genetic tests/referrals among minority-serving physicians emphasizes the importance of tracking the diffusion of genomic medicine and assessing the potential impact on health disparities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

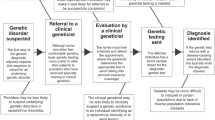

Genomic medicine is expected to substantially improve the quality and efficacy of health care by providing new insight into the etiology of disease and facilitating individually-tailored prevention and treatment regimens.1,2 Genetic testing is now recommended to guide prevention strategies such as identifying patients at increased risk of breast, ovarian, or colon cancer and various treatment decisions.3–9 Emerging genomics research on highly prevalent complex illnesses (e.g., diabetes, asthma, cardiovascular disease, nicotine dependence) promises wider diffusion of genomic medicine in the future and a greater role for primary care physicians (PCPs) as “frontline providers” of genetic services.10–13 It is precisely through advances in the treatment and prevention of highly prevalent conditions that genomics has the greatest potential to improve population health and reduce health disparities—but only if PCPs are prepared to incorporate genomic medicine into practice and if such interventions reach those most in need.14,15

PCPs face several challenges in utilizing genetic tests to enhance clinical care. Most have little experience or training relevant to genetic testing, and many lack confidence and skill in this area of practice.16,17 This lack of knowledge and experience is compounded by pressures to provide a seemingly ever expanding scope of services within the tight time constraints of a typical office visit, making it difficult to deliver preventive or elective services or to incorporate new technologies into practice.18,19

It is likely that primary care practices serving high concentrations of minority, uninsured, low-income, or low English proficiency patients—patient groups that already bear a disproportionate burden of illness—will face even greater difficulties integrating genomic medicine into clinical practice.20–23 A recent study by Bach et al.,24 for example, found that the 22% of US physicians who serve 80% of all black Medicare beneficiaries were far less likely to be board certified and far more likely to report difficulty providing high quality care for their patients compared with nonminority serving physicians. The few available studies addressing disparities in access to genetic testing focus on cancer susceptibility screening. Early evidence suggests that black women have reduced access to genetic counseling and screening for BRCA1/2.25 Other studies have documented reduced awareness and use of cancer genetics services among minority patients.26–28

No study to date has assessed utilization of currently available genetic tests among PCPs nationally, whether through referral or directly, nor examined whether there is differential use of available genetic tests among policy-relevant subsets of providers—in particular, those who disproportionately serve minority or other vulnerable patient populations. In this study, we assessed physicians' experience ordering or referring patients for available genetic tests among a random sample of 2000 PCPs in the United States. We also assessed utilization of available genetic tests among providers serving a disproportionate number of minority patients relative to their peers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample selection

A simple random sample of 2000 PCPs (defined here as a primary specialty of internal medicine, family practice, or general practice) was drawn from all US PCPs in the American Medical Association (AMA) Masterfile (N = 218,186) through an authorized vendor.29 The Masterfile lists all US physicians who have met educational and credentialing requirements regardless of whether they are AMA members or not. We restricted eligibility to respondents who practiced direct patient care at least 20 hours per week. Differences between characteristics of our sample and of the underlying population were within range of sampling variation for specialty distribution, age, and sex.17

Selection of genetic tests to be studied

Through focus groups with PCPs, review of the literature, and consultation with experts in clinical genetics, we selected four examples of available genetic tests as case studies for exploring the extent to which genomic medicine has been integrated into primary care practice through PCPs' referral to specialty care or direct ordering of tests. Selected cases included testing for inherited risk of breast/ovarian cancer and colon cancer, as leading examples of genetic susceptibility testing to guide preventive care; testing for Huntington disease, as a frequently cited example of genetic testing for a rare genetic disease; and sickle cell testing, which is used in the diagnosis of sickle cell disease and in the assessment of reproductive risk and is of particular importance to African Americans. Specific guidelines for testing are available for each of these genetic tests.9,30–32

Survey design and administration

Development of the survey instrument was informed by five focus groups and semistructured interviews with PCPs; comments from key physician organizations; and review of the literature. Data collection was conducted from May to November, 2002. This survey was approved by the institutional review boards of Georgetown University (Principal Investigator's former institution) and the University of Massachusetts Boston. Given our interest in surveying the attitudes of physicians engaged primarily in clinical practice, only those who spent a minimum of 20 hours per week in direct patient care were included in the study. The final response rate, adjusted for ineligible cases, was 62.3%. Further details of survey design and administration procedures are available elsewhere.17

Measures

Dependent variables

Experience ordering available genetic tests.

We asked PCPs whether they had ever ordered a genetic test for four specific conditions (breast cancer, colon cancer, Huntington disease, or sickle cell) or “for any other condition” (yes/no). A summary variable (“ever ordered”) was constructed identifying physicians who had ever ordered any of the four specific genetic tests or “any other genetic test.”

Experience referring patients for genetic testing.

We asked PCPs: “Have you ever referred a patient for a genetic test to (a) a genetic counseling center or a genetic counselor; (b) a specialist for the patient's condition; (c) a clinical research trial; or (d) any other site of care?” A summary variable identifying experience referring to any of these sites of care was also constructed.

Finally, we created an overall summary variable indicating physicians who reported having “ever ordered” a genetic test or having “ever referred” a patient to any other site for genetic testing.

Independent variables

Key to this analysis was the self-reported proportions (0–100%) of physicians' patient panels comprised of patients from racial/ethnic minority communities. For our purposes, minority-serving physicians were defined as those physicians ranking within the top quintile in the distribution of the respondents' self-reported proportion of patients who are from minority communities. Among this group of “minority-serving physicians,” more than 50% of their patients were from minority communities.

Indicators for physicians serving a high proportion of patients on Medicaid, who had a primary language other than English, or who were uninsured were similarly constructed and used as control variables in all analyses. The top quintile in the distribution of each of these patient subpopulations represented physicians whose patient panels included 30% or more Medicaid patients, 20% or more patients with a primary language other than English, and 15% or more patients who were uninsured, respectively.

Physician characteristics included age, self-identified race/ethnicity, primary specialty, and whether one had a full-time faculty appointment. Practice size was characterized as 1–2 physicians or larger. Practice location was characterized according to Census region.

We assessed whether physicians had received any formal training in clinical genetics and, if so, whether they had received training in medical school or medical residency and/or in continuing medical education (CME) courses. Knowledge of existing privacy and antigenetic discrimination protections as they relate to health insurance was assessed with the question, “Under current federal law, can health insurance companies use genetic test results to increase patients' health insurance premiums or deny health insurance coverage in (a) the group market? and (b) the individual market?”, with “yes,” “no,” and “don't know” response options for each. Those responding correctly that current protections in Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act apply only to those with group health insurance coverage were identified as having accurate knowledge of current legal protections.33

To assess physicians' preparedness to incorporate genetics into clinical practice, we asked, “How prepared do you feel to counsel patients considering a genetic test?” and, “How confident are you in your ability to interpret the results of a genetic test?” We also asked physicians how optimistic they were that genetics research will lead to significant improvements in the treatment of complex traits. Responses to each of these three items were scaled as “very,” “somewhat,” “a little,” and “not at all.” For our analyses, we dichotomized responses as “very” versus less than “very.” Finally, we assessed the impact of individual physicians' attitudes toward new treatments or technologies by identifying those physicians who said they tended to offer new diagnostic tests “before most of their peers.”

Statistical analysis

Bivariate analyses were conducted to assess relationships between experience ordering genetic tests or referring patients for genetic testing and each of the independent variables using χ2 statistics. Separate multivariate logistic regressions were conducted to identify factors associated with each of the 10 dependent variables. All analyses were conducted using Intercooled Stata 9.2 for Microsoft Windows (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). Our final models included the following set of covariates: patient-mix characteristics (high proportion minority, Medicaid, patients with a primary language other than English, and uninsured patients); practice characteristics (number of physicians, practice setting, and region); physician characteristics (age, self-identified race/ethnicity, and specialty); training in clinical genetics via medical school/residency or CME; knowledge of current privacy protections affecting the impact of genetic information on access to affordable health insurance; preparedness to counsel patients considering genetic testing; confidence interpreting genetic test results; and self-identification as an early adopter of new diagnostic tests. All statistics were adjusted using survey weights designed to correct for minor differences in response rate across specialties relative to the national distribution of internists, family practitioners, and general practitioners in the AMA Masterfile. For any given variable, there were fewer than 4.9% missing observations and no observed patterns of missing data.

RESULTS

Descriptive results

Of the 2000 PCPs selected from the AMA Masterfile, 1798 met the eligibility criterion of practicing direct patient care at least 20 hours per week. Of these, 1120 (62.3%) completed the survey.

Nationally, approximately 60% of PCPs reported having ever ordered a genetic test for any condition, 74% of physicians reported having ever referred a patient for genetic testing, and 82% had ever ordered or referred a patient for genetic testing (Table 1). With respect to specific conditions, 27% of physicians had ever ordered a genetic test for breast cancer, 17% for colon cancer, 37% for sickle cell disease, and 17% for Huntington disease (Table 2). With respect to referrals for genetic testing, approximately 62% of physicians reported having referred a patient to a genetics center or counselor, 62% to a specialist for the patient's condition, and 17% to a clinical trial.

Minority-serving physicians were significantly less likely to have ever ordered a genetic test to assess breast cancer risk (18% vs. 29%; P = 0.01), colon cancer risk (11% vs. 18%, P = 0.05), or Huntington disease (6% vs. 18%; P < 0.001) compared with those serving fewer minority patients (Table 2). Minority-serving physicians were also significantly less likely to have ever referred a patient for genetic testing to a genetics center or counselor (52% vs. 64%; P < 0.001), a specialist for the patient's condition (52% vs. 64%; P < 0.001), a clinical trial (10% vs. 18%; P = 0.03), or to any site of care (63% vs. 76%; P < 0.001).

Adjusted analyses

Experience ordering available genetic tests

Controlling for a broad range of physician and practice characteristics, as well as patient-mix characteristics, minority-serving physicians were significantly less likely than their peers who serve fewer minority patients to have ever ordered a genetic test for breast cancer (OR: 0.42; 95% CI: 0.0.23–0.79; P < 0.01), colon cancer (OR: 0.39; 95% CI: 0.19–0.80; P < 0.01), and Huntington disease (OR: 0.21; 95% CI: 0.08–0.53; P < 0.001) (Table 3).

Physicians over age 65 were less likely to have ever ordered a genetic test relative to younger physicians (OR: 0.51; 95% CI: 0.30–0.86; P < 0.05). Physicians who had received training in clinical genetics in medical school or through CME courses had nearly double the odds of having ever ordered a genetic test relative to peers without such training to (OR: 1.89, 95% CI: 1.39–2.57; P < 0.001 and OR: 1.80, 95% CI: 1.34–2.43; P < 0.001, respectively), as were physicians with an accurate knowledge of current privacy and antigenetic discrimination protections (OR: 2.09, 95% CI: 1.19–3.69; P < 0.05). Those who felt very prepared to counsel patients considering genetic testing (OR 3.13, 95% CI: 1.20–8.17; P < 0.05) and early adopters of new diagnostic tests (OR: 2.03; 95% CI: 1.31–3.13; P < 0.01) were also more likely to have ever ordered a genetic test.

Experience referring patients for genetic testing

With respect to referrals for genetic testing, minority-serving physicians were less likely to have ever referred a patient to a clinical trial for genetic testing (OR: 0.46; 95% CI: 0.22–0.96; P < 0.05) or referred a patient to any site of care for genetic testing (OR: 0.60; 95% CI: 0.36–0.99; P < 0.05) compared with physicians serving fewer minority patients (Table 4). Physicians serving a disproportionate share of Medicaid patients were also significantly less likely than those serving fewer Medicaid patients to have ever referred a patient to a genetics center or counselor for genetic testing (OR: 0.58; 95% CI: 0.37–0.92; P < 0.05) or referred a patient to any site of care for genetic testing (OR: 0.49; 95% CI: 0.30–0.80; P < 0.01).

PCPs in solo or two-physician practices were less likely (OR: 0.65; 95% CI: 0.44–0.97; P < 0.05) than those in larger practices to have ever referred a patient for genetic testing, as were older physicians. Those in family practice had more than twice the odds of having ever referred a patient for genetic testing relative to internists (OR: 2.56; 95% CI: 1.81–3.61; P < 0.001). Physicians who had received training in clinical genetics through CME courses were significantly more likely (OR: 2.21; 95% CI: 1.56–3.13; P < 0.001) to have ever referred a patient for a genetic test compared with peers without such training, whereas those with an accurate knowledge of current privacy and antidiscrimination statutes as they pertain to access to affordable health insurance had six times the odds (OR: 6.13; 95% CI: 2.21–16.99; P < 0.001) of ever having referred a patient for genetic testing compared with those without such knowledge.

DISCUSSION

This study provides baseline estimates regarding the extent to which PCPs in the United States have integrated genetic testing and referral into clinical practice. We further evaluated whether PCPs who serve a high proportion of minority and other underserved patient populations were less likely than their peers to have ever ordered a genetic test or to have ever referred a patient for genetic testing to other sites of care.

Our results show that while roughly two-thirds of US PCPs have ever ordered a genetic test and more than three-quarters of physicians have ever referred a patient for genetic testing, minority serving physicians are significantly less likely to have such experience. Specifically, minority-serving physicians were significantly less likely to have ever ordered a genetic test for three of the four cases studied, or to have ever referred a patient to a clinical trial for genetic testing or to any site of care compared with physicians serving proportionately fewer minority patients.

Providers who disproportionately serve minority patients may differ systematically from physicians who serve predominantly white patients. A recent study by Bach et al.24 found that minority-serving physicians were less likely to be board certified and had greater difficulty providing high quality care to their patients. If these differences apply to minority-serving physicians generally, they may indicate obstacles in terms of training and availability of genetics services that do not affect clinicians serving majority populations.

Minority-serving physicians may also be responding to differences in patient preferences that track with race/ethnicity. Early studies of women participating in research trials showed that black women had less knowledge and less positive attitudes about the value of genetic testing for BRCA1/2 and were less motivated to pursue testing relative to white women.34–36 Other studies showed that blacks tended to value predictive genetic testing less than whites.37 Most recently, Armstrong et al.25 found that black women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer were much less likely than white women to undergo genetic counseling for BRCA1/2, controlling for differences in the probability of carrying a BRCA1/2 mutation, socioeconomic status, cancer risk perception, and worry, attitudes about BRCA1/2 testing, or PCP discussions of testing. Several studies report that the prevalence of significant mutations is similar in black and white women with a family history of breast cancer, suggesting that black and white women would be expected to benefit equally from predictive genetic testing.38,39 The low rates of ordering genetic tests for Huntington disease among minority-serving physicians may reflect early studies suggesting a lower prevalence of Huntington disease among blacks compared with whites, although more recent data report similar prevalence rates across white and black populations.40–42 Although minority patients may benefit from genetic testing as much as nonminority patients, if minority patients are sicker and have more complex health needs than majority patients, these health issues may crowd out the provision of genetic services. Further research is needed to understand whether differences in physicians' utilization of available genetic tests reflects patient preferences, patient health, or whether providers are less likely to offer minority patients genetic testing.

Low referral rates to genetics centers, counselors, or other resources among physicians serving a large proportion of Medicaid enrollees also deserve further investigation. The Medicaid program currently covers 44.4% of the nation's low-income patients,43 and thus is a sentinel population for tracking health disparities along socioeconomic lines. Previous studies have documented reduced access to specialty services and new technologies among Medicaid patients relative to commercially insured patients.44–46 Recent reductions in Medicaid spending per beneficiary threaten to exacerbate such disparities in access to care.47

Study results also emphasize the importance of physician education in preparing physicians to incorporate genetics into clinical practice. In our study, physicians who had received training in clinical genetics in medical school or through CME were far more likely to have ever ordered a genetic test or referred a patient for genetic testing. Sustained educational efforts aimed at PCPs will be key to successful clinical integration of new genetic applications. Strategies should be developed to ensure that physician education and outreach efforts reach those who disproportionately serve minority patients and other underserved groups.

Physicians in solo or two-physician practices were substantially less likely to have ever ordered or referred a patient for genetic testing. Innovative strategies will need to be developed to minimize the burden of incorporating genetics into clinical practice, particularly for solo and small group practices. The development of clinical guidelines and other mechanisms to support clinical decision-making will be needed.48

In our analysis, family practice physicians were significantly less likely than internists to have ever ordered a genetic test, but were far more likely to have referred a patient for genetic testing to a genetics center or counselor, a specialist for the patient's condition, or to any site. In many cases, referral likely reflects an appreciation for the detailed counseling recommended as part of the testing process.9,16,31 Future efforts to monitor access to available genetic tests will need to take into consideration both direct provision of genetic services and referrals for such services.

Results of this study should be viewed within the context of certain study limitations. We relied on physicians' self-report to assess their experience ordering genetic tests or referring patients to other sites for genetic testing. Although previous research has demonstrated that self-reported information provided by physicians is closely associated with actual physician practice, and may more accurately reflect physician behavior than chart abstraction, reported results were not validated in claims or other data.49–51 We similarly relied on physicians' self-report regarding the composition of their patient panels. These estimates may not be precise, yet we believe they are useful and valid for distinguishing physicians with extremely high numbers of minority patients. Although data for this study were collected through 2002, these data provide the first national estimates of PCPs' use and referrals for available genetic tests, and reflect a time frame similar to the most recent estimates on racial differences in genetic testing for BRCA1/2 published in 2006, for which data were collected in 1999–2003.25

There has been a dramatic investment in genomics research in recent years, and expectations remain high that genomic medicine will significantly improve clinical outcomes and population health. Our findings raise the possibility that these improvements will be less likely to reach minority and other underserved populations because the PCPs who serve them are less likely to provide access to genomic medicine. To the extent that genomic medicine appreciably improves the quality of care and clinical outcomes, ensuring equitable access to emerging genetic-based treatments will be an essential component of any comprehensive strategy to eliminate health disparities.

References

Collins FS, Guttmacher AE . Genomics moves into the medical mainstream. J Am Med Assoc 2001; 286: 2322–2324.

Roses AD . Pharmacogenetics and the practice of medicine. Nature 2000; 405: 857–865.

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Prenatal and preconceptual carrier screening for genetic diseases in individuals of eastern European Jewish descent: ACOG Committee Opinion No 298. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2004.

Cobleigh MA, Vogel CL, Tripathy D, Robert NJ, et al. Multinational study of the efficacy and safety of humanized anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody in women who have HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer that has progressed after chemotherapy for metastatic disease. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 2639–2648.

GeneTests: medical genetics information resource. University of Washington, Seattle. Available at: http://www.genetests.org. Accessed June 26, 2005.

Skinner MA, Moley JA, Dilley WG, Owzar K, et al. Prophylactic thyroidectomy in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 1105–1113.

Spear BB, Heath-Chiozzi M, Huff J . Clinical application of pharmacogenetics. Trends Mol Med 2001; 7: 201–204.

Umar A, Boland C, Terdiman J, Syngal S, et al. Revised Bethesda guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004; 96: 261–268.

US Preventive Services Task Force Genetic risk assessment and BRCA mutation testing for breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2005; 143: 355–361.

Danoviz ME, Pereira AC, Mill JG, Krieger JE . Hypertension, obesity and GNB 3 gene variants. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2006; 33: 248–252.

Horikawa Y, Oda N, Cox NJ, Li X, et al. Genetic variation in the calpain 10 gene (CAPN10) is associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Genet 2000; 126: 163–175.

Hotlzman NA . Primary care physicians as providers of frontline genetic services. Fetal Diagn Ther 1993; 8( suppl 1): 213–219.

Lerman C, Berrettini W . Elucidating the role of genetic factors in smoking behavior and nicotine dependence in men. Am J Med Genet 2003; 118B: 48–54.

Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2002.

Yach D, Hawkes C, Gould L, Hofman K . The global burden of chronic diseases. J Am Med Assoc 2004; 291: 2616–2622.

Burke W, Emery J . Genetics education for primary-care providers. Nat Rev Genet 2002; 3: 561–566.

Shields AE, Blumenthal DB, Weiss KB, Comstock CB, et al. Barriers to translating emerging genetics research on smoking into clinical practice: perspectives of primary care physicians. J Gen Intern Med 2005; 20: 131–138.

Blumenthal D, Causino N, Chang YC, Culpepper L, et al. The duration of ambulatory visits to physicians. J Fam Pract 1999; 48: 264–271.

Rich EC, Burke W, Heaton CJ, Haga S, et al. Revitalizing the family history in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2004; 19: 273–280.

Fiscella K, Franks P . Does the content of primary care visits differ by the racial composition of physicians' practices?. Am J Med 2006; 119: 348–353.

Groeneveld PW, Laufer SB, Garber AM . Technology diffusion, hospital variation, and racial disparities among elderly Medicare beneficiaries 1989–2000. Med Care 2005; 43: 320–329.

Hall MJ, Olopade OI . Disparities in genetic testing: thinking outside the BRCA box. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 2197–2203.

Schneider EC, Zaslavsky AM, Epstein AM . Racial disparities in the quality of care for enrollees in Medicare managed care. J Am Med Assoc 2002; 287: 1288–1294.

Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, et al. Primary care physicians who treat blacks and whites. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 575–584.

Armstrong K, Micco E, Carney A, Stopfer J, et al. Racial differences in the use of BRCA1/2 testing among women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer. J Am Med Assoc 2005; 293: 1729–1736.

Hall MJ, Olopade OI . Confronting genetic testing disparities: knowledge is power. J Am Med Assoc 2005; 293: 1783–1785.

National Center for Health Statistics. Chartbook on trends of health of Americans: National Health Interview Survey 2000. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2002.

Wideroff L, Vadaparampil ST, Breen N, Croyle RT, et al. Awareness of genetic testing for increased cancer risk in the year 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Community Genet 2003; 6: 147–156.

American Medical Association. AMA Masterfile. Synavant, Fairhaven, NJ, 2002.

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Genetic screening for hemoglobinopathies: ACOG committee opinion. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2000.

International Huntington Association and the World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Huntington's Chorea. Guidelines for the molecular genetics predictive test in Huntington disease. J Med Genet 1994; 31: 555–559.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to clinical preventive services. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1996.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996. Public Law 104–191. 104th Congress, 1996.

Hughes C, Gomez-Caminero A, Benkendork JL, Kerner J, et al. Ethnic differences in knowledge and attitudes about BRCA1 testing in women at increased risk. Patient Educ Couns 1997; 32: 51–62.

Hughes C, Lerman C, Lustbader E . Ethnic differences in risk perception among women at increased risk for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1996; 40: 25–35.

Lerman C, Caporaso NE, Audrain J, Main D, et al. Evidence suggesting the role of specific genetic factors in cigarette smoking. Health Psychol 1999; 18: 14–20.

Peters N, Rose A, Armstrong K . The association between race and attitudes about predictive genetic testing. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2004; 13: 361–365.

Gao Q, Tomlinson G, Das S, Cummings S, et al. Prevalence of BRACA1 and BRACA2 mutations among clinic-based African American families with breast cancer. Hum Genet 2000; 107: 186–191.

Olopade OI, Fackenthal JD, Tainsky MA, Collins F, et al. Breast cancer genetics in African Americans. Cancer 2003; 97( suppl 1): 236–245.

Folstein SE, Chase GA, Wahl WE, McDonnell AM, et al. Huntington disease in Maryland: clinical aspects of racial variation. Am J Hum Genet 1987; 41: 168–179.

Reed TW, Chandler JH, Hughes EH, Davidson RT . Huntington's chorea in Michigan. I. Demography and genetics. Am J Hum Genet 1958; 10: 210–225.

Wright HM, Still CN, Ramson RK . Huntington disease in black kindreds in South Carolina. Arch Neurol 1981; 38: 412–414.

Fronstin P . Sources of health insurance and characteristics of the uninsured: analysis of the March 2006 current population survey. Issue brief no. 298. Washington: Employee Benefit Research Institute, 2006.

Blumenthal D, DesRoches C, Donelan K, Ferris T, et al. Health information technology in the United States: the information base for progress. Princeton: Robert Woods Johnson Foundation, 2006.

Bosco LA, Gerstman BB, Tomita DK . Variations in the use of medication for the treatment of childhood asthma in the Michigan Medicaid population, 1980–1986. Chest 1993; 104: 1727–1733.

Skaggs DL, Clemens S, Vitale MG, Femino JD, et al. Access to orthopaedic care for children with government versus private insurance in California. Pediatrics 2001; 107: 1405–1408.

Smith V, Ramesh R, Gifford K, Ellis E, et al. The continuing Medicaid budget challenge: state Medicaid spending growth and cost containment in fiscal years 2004 and 2005. The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation, 2004.

Freedman AN, Wideroff L, Olson L, Davis W, et al. US physicians' attitudes toward genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. Am J Med Genet 2003; 120A: 63–71.

Carey TS, Garrett J . Patterns of ordering diagnostic tests for patients with acute low back pain. The North Carolina Back Pain Project. Ann Intern Med 1996; 125: 807–814.

Mandelblatt JS, Berg CD, Meropol NJ, Edge SB, et al. Measuring and predicting surgeons' practice styles for breast cancer treatment in older women. Med Care 2001; 39: 228–242.

Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, et al. Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. J Am Med Assoc 2000; 283: 1715–1722.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NHGRI P20 HG003400 (to A.E.S.) and The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (to A.E.S.). Dr. Burke's contribution of interpretation of data and preparation and review of this article was supported by NHGRI P50 HG003374.

The authors thank Mary McGinn-Shapiro, BA and Emily J. Youatt, BA (Harvard/MGH) for research assistance. We also thank Douglas Currivan, PhD (Research Triangle Institute) for statistical advice; Catherine Comstock (independent consultant) for programming assistance; and David Blumenthal and Lisa Iezzoni (MGH/Harvard) for valuable comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shields, A., Burke, W. & Levy, D. Differential use of available genetic tests among primary care physicians in the United States: results of a national survey. Genet Med 10, 404–414 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181770184

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181770184

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Ordering genetic testing by neurologists: points to consider

Journal of Neurology (2023)

-

Evaluating cancer genetic services in a safety net system: overcoming barriers for a lasting impact beyond the CHARM research project

Journal of Community Genetics (2023)

-

Disparities in germline testing among racial minorities with prostate cancer

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2022)

-

Study protocol: the Australian genetics and life insurance moratorium—monitoring the effectiveness and response (A-GLIMMER) project

BMC Medical Ethics (2021)

-

Adherence to National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines for BRCA testing among high risk breast Cancer patients: a retrospective chart review study

Hereditary Cancer in Clinical Practice (2020)