Abstract

A solvent-free fabrication of TiO2 and ZnO nanonetworks is demonstrated by using supramolecular nanotemplates with high coating conformity, uniformity and atomic scale size control. Deposition of TiO2 and ZnO on three-dimensional nanofibrous network template is accomplished. Ultrafine control over nanotube diameter allows robust and systematic evaluation of the electrochemical properties of TiO2 and ZnO nanonetworks in terms of size-function relationship. We observe hypsochromic shift in UV absorbance maxima correlated with decrease in wall thickness of the nanotubes. Photocatalytic activities of anatase TiO2 and hexagonal wurtzite ZnO nanonetworks are found to be dependent on both the wall thickness and total surface area per unit of mass. Wall thickness has effect on photoexcitation properties of both TiO2 and ZnO due to band gap energies and total surface area per unit of mass. The present work is a successful example that concentrates on nanofabrication of intact three-dimensional semiconductor nanonetworks with controlled band gap energies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Interest in developing novel fabrication strategies at the nanometer scale has continued to rise over the last decade. The main motivations behind crafting materials at smaller dimensions have been to increase the surface-to-volume ratio and to reduce diffusion path length. Nano-crafted materials can also manifest emergent electronic and optical properties1. Superior control over the size, shape and uniformity of the materials constitute the principal parameters within the context of nanofabrication. Materials in different size and architectures, such as, zero-dimensional nanoparticles; one-dimensional nanowires, nanotubes; two-dimensional nanosheets; and three-dimensional mesoporous structures and nanonetworks have been fabricated and their properties in desired applications have been closely investigated2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Among these, nanonetwork architecture, which can be defined as isotropically distributed, three-dimensional interconnected nanowires, draws particular attention for its high surface area and porosity, which allow robust interaction with the solvent and solute molecules. Interconnected intact structure of the nanonetwork, extending millimeter-to-centimeter scales, provides practical applicability in device designs. Various materials fabricated in the structure of nanonetwork exhibited superior performance in energy, sustainability and biomedical applications3,11,12,13,14,15.

Template-directed mineralization is regarded as a promising nanofabrication strategy, because both physical and chemical cues presented by the template allow control over the size and structure of the resulting materials. As opposed to hard (inorganic) templates, soft (organic) templates are particularly attractive due to relative ease of modification over the chemical functionality, architecture diversity and physical properties of the template5,9. However, low chemical stability at high temperature, liability to organic solvents and fast chemical degradation remain as the major challenges with organic templates16. Incomplete template coverage and thickness control are the further challenges in organic templates4. Maintaining structural conformity and uniformity of the deposit is another unresolved issue on macroscopic three-dimensional templates (mm-to-cm scale) having nanoscale architecture with ultra-high-aspect-ratio components.

TiO2 and ZnO nanostructures have been widely used in photocatalytic self-cleaning surfaces, piezoelectric devices, chemical sensing and dye-sensitized solar cell applications mainly due to their suitable electrochemical properties, excellent solution stability and relatively low toxicity4,15,17,18,19. Having relatively high band gap energies (3.00–3.30 eV), TiO2 and ZnO can generate excited-state conduction-band electrons and valence-band holes with large redox potential differences upon photoexcitation in the ultraviolet domain of the spectrum. This property has been utilized for a variety of photocatalytic applications in aqueous environment, such as artificial photosynthesis, decomposition of potentially toxic organic materials, cancer treatment and hydrogen gas production for clean, renewable energy20. A convenient, template-based manufacturing of these materials in nanoscale is of particular significance.

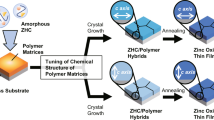

Motivated by our recent work on bioinspired supramolecular template directed nanostructure fabrications5,9,21, bioinspired peptide nanofiber templates (5–7 nm in diameter) combined with an atomic-layer controlled thin-film deposition technique can form a nanofabrication platform to efficiently fabricate transition metal compounds on a nanonetwork template. Here, we describe utilization of bioinspired self-assembled peptide nanonetwork as template for fabrication of TiO2 and ZnO nanonetwork semiconductors (Fig. 1). For this purpose, we designed and synthesized a mussel-inspired peptide amphiphile molecule, Dopa-PA, which efficiently self-assembles into mechanically intact nanofibrous network with thin fiber diameter (6.3 ± 1.0 nm) having good adhesive properties to the solid support22,23,24. These three-dimensional nanofibrous peptide nanonetworks can reach to the length scales of millimeter and centimeter in all three dimensions. We demonstrate that TiO2 and ZnO nanonetworks can be reliably deposited on dried self-assembled peptide nanonetwork template with significant uniformity and exceptionally high conformity via atomic layer deposition (ALD) technique25. Due to separate dosing of reactive gaseous precursors and limited number of surface reaction sites, ALD is intrinsically self-limiting. This unique reaction property leads to uniform and highly conformal deposition on ultra-high-aspect-ratio surfaces (>1000) where conventional sol-gel, chemical and physical vapor deposition techniques fall short25. In a typical ALD process, growth per cycle (GPC) is constant and in the order of angstrom level. Furthermore, gaseous precursor molecules could directly penetrate inside the porous structures without mechanically destroying, or dissolving, relatively weak organic architecture at comparatively lower temperatures26.

Strategy for three-dimensional nanofabrication of TiO2 and ZnO nanonetworks on supramolecular nanofibers of peptide amphiphile nanonetwork.

(a). Chemical sketch of Dopa-PA, the building block of the self-assembled network. (b). TEM micrograph showing self-assembled nanofibers at pH 10. (c). The pH-dependent gelation of Dopa-PA network in water and controlled removal of the solvent through critical point drying. (d). Three-dimensional macrostructure (left) of the nanofibrous template (SEM image, right) after drying. t is the thickness, D is the diameter of the template used for ALD. (e). A schematic representation of TiO2 and ZnO organic-inorganic core-shell nanonetwork formation through ALD.

The TiO2 and ZnO nanonetworks produced by peptide nanofibrous network templates and ALD technique were characterized by XRD, XPS, TGA, SEM, TEM and EDX. Since deposition occurs at the atomic scale, we systematically evaluated the electrochemical properties of TiO2 and ZnO nanonetworks and studied size-function relationship.

Results

Synthesis and preparation of the peptide template for ALD

Self-assembly of peptide molecules into high-aspect-ratio nanofibers was triggered by increase of the pH of the peptide solution to ~ 10 (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. S1). Individual nanofibers forming the hydrogel network were determined to be 6.3 ± 1.0 nm in diameter and several tens of micrometers in length by TEM. Nevertheless, few bundles of nanofibers, in the range of 10.6–28.3 nm in diameter, were also observed. SEM images showed that the drying procedure did not cause any noticeable damage on the structure of the network (Fig. 1d). In addition, there were no macro level cracks and no shrinkage in the dimensions of the network upon drying.

Characterization of TiO2 and ZnO nanonetworks

Dopa-PA nanonetworks were coated with TiO2 and ZnO separately, forming organic-inorganic core-shell nanostructures, as schematically shown in Figure 1e. SEM images revealed nanofibrous networks of TiO2 and ZnO deposited with 350 and 100 ALD cycles, respectively (Fig. 2a–b, e–f). The inorganic nanofibers are interconnected to each other forming continuous three-dimensional network structures. The whole inorganic network was true replica of the core peptide network. Both TiO2 and ZnO core-shell nanonetworks remained intact after atomic layer deposition, resulting in one whole nanonetwork in mm to cm scale. Both energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) (Fig. 2c, g and Supplementary Fig. S4) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (Supplementary Fig. S3a–b) independently confirmed the TiO2 and ZnO deposition. High resolution XPS scans of Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2 peaks located at 459.2 and 465.2 eV, respectively and Zn 2p3/2 and Zn 2p1/2 peaks located at 1044.8 and 1021.8 eV, respectively, were in agreement with the previously reported data for TiO2 and ZnO27,28,29,30. Thermogravimetric analyses (TGA) revealed that 68.74% of the organic-inorganic composite structure consisted of TiO2 and 85.51% was ZnO (Supplementary Fig. S3c). In terms of surface morphology, TiO2 shell was smooth along the length of the nanofibers while ZnO shell was more irregular depending on the crystal structure of the nanotubes. Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface areas for these nanonetworks were estimated to be 34.54 m2/g for as-synthesized (without calcination) TiO2 and 93.99 m2/g for as-synthesized ZnO. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis showed that as-synthesized TiO2 nanonetwork was amorphous (Fig. 2d). Anatase phase of TiO2 is known to be the most efficient morphology with a band gap energy of 3.2 eV and suitable band-edge positions to split water into highly oxidative hydroxyl radicals and peroxides7. A common strategy for the phase transition is to anneal the amorphous TiO2 at sufficiently high temperatures. Anatase phase can be obtained by calcination at 300–500°C, while > 550°C is required for rutile phase transformation at ambient conditions. Accordingly, we calcined TiO2 nanonetwork at 450°C. An amorphous-to-anatase phase transition took place while the nanofibrous network was thoroughly preserved (Fig. 3a–d)31. On the other hand, as-synthesized ZnO nanonetwork exhibited hexagonal wurtzite crystal structure (Fig. 2h). This is thermodynamically the most stable phase of ZnO at ambient conditions having the same band gap energy of anatase TiO2 (3.2 eV)19. Calcination of this network at 450°C did not alter the nanonetwork architecture and its crystal structure (Fig. 3e–h).

Characterization of calcined TiO2 and ZnO nanonetworks prepared by the deposition of 350 and 100 ALD cycles, respectively.

(a, b). SEM images, (c). EDX spectrum and (d). XRD pattern of TiO2 nanonetwork corresponding to anatase phase. (e, f). SEM images, (g). EDX spectrum and (h). XRD pattern of ZnO nanonetwork corresponding to a wurtzite structure.

Atomic layer size control of the semiconductor nanotubes

The diameter of TiO2 nanotubes linearly decreased from 52.0 ± 5.0 to 13.4 ± 1.8 nm with decreased ALD cycles from 350 to 50. In the same trend, the diameter of ZnO nanotubes linearly decreased from 37.4 ± 5.6 (100 cycles) to 13.9 ± 2.4 nm (25 cycles) (Fig. 4). Growth per cycle (GPC) was found to be 0.56 Å for TiO2 and 1.55 Å for ZnO (Fig. 4b,d, Supplementary Figure S6 and Supplementary Table 1). The growth rates on three-dimensional networks were in good agreement with spectroscopic ellipsometry measurements acquired on flat silicon surfaces coated with TiO2 and ZnO by using the same ALD method. After calcination, the diameter of TiO2 and ZnO nanotubes negligibly changed (Supplementary Fig. S7). In ZnO nanotubes, we observed morphological differences in TEM images. The peptide cores were filled with ZnO crystals while the total diameter remained same as before calcination. ZnO nanotubes formed a necklace-like structure at 20 nm and smaller nanotube diameters. On the other hand, the network underwent sintering at 10 nm and the integrity of the fibrous architecture was largely lost.

Size-controlled deposition of TiO2 and ZnO on peptide nanonetwork template through ALD cycle number.

Representative TEM images of as-synthesized (a). TiO2, (c). ZnO nanotubes at varying ALD cycle numbers, which facilitate fabrication of the core-shell nanotubes at desired diameters. Images also show high levels of coating conformality on peptide nanofibers. (b, d). Deposition parameters: wall thicknesses, nanotube diameters and growth per cycle (GPC), as a function of the number of ALD cycles for TiO2 and ZnO, respectively. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Size-function relationship

As TiO2 and ZnO nanonetworks with tuned thicknesses (from ~ 13 nm to ~ 50 nm diameters with ~ 3 nm to ~ 20 nm wall thicknesses) were easily prepared by simply altering the number of ALD cycles, we safely explored the relationship between band gap energy and wall thickness (or nanotube diameter) (Supplementary Table S1). In the UV-Vis absorption spectra of the nanonetworks, significant hypsochromic shifts (Δλ = 10–20 nm) were observed for both anatase TiO2 and wurtzite ZnO as the wall thicknesses decreased below approximately 8 nm (Fig. 5), indicating an increase in energy gap between valence band and conduction band states. In parallel, we also noted a dramatic decrease of the relative absorbance at the photoexcitation wavelength (365 nm) when the wall thicknesses are below 8 nm. The photocatalytic activities of both semiconductors exhibited considerable decrease below the wall thicknesses ~ 8 nm. For TiO2 nanonetworks, methylene blue degradation rate increased as the wall thickness decreased from 19.7 nm to 8.7 nm (Fig. 6a). For ZnO nanonetworks, methylene blue degradation rate remained almost the same (with barely detectable increase) as the wall thickness decreased from 15.5 nm to 8.3 nm (Fig. 6b). However, this trend sharply deviated at 3.1 nm and 3.8 nm for TiO2 and ZnO, respectively.

Photoexcitation of surface-immobilized TiO2 and ZnO nanonetworks

Semiconductor nanonetworks were further prepared on solid supports by using peptide nanofiber templates as shown in Figure 1. As a control, flat inorganic substrates without peptide nanofiber template were also prepared by ALD with the same average wall thickness of the constituent nanotubes. Under UV irradiation, 69% and 63% of methylene blue was degraded by the end of 7 h by using peptide nanofiber templated TiO2 and ZnO networks, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S9). Methylene blue degradation by non-templated TiO2 and ZnO catalysts, however, remained only at 7% and 9%, respectively. The photoexcitation efficiency of templated TiO2 nanonetwork was 2.62 folds (calculated based on the t1/2 templated/t1/2 non-templated ratio) greater than that of non-templated solution-synthesized anatase TiO2 (Supplementary Fig. S10a–c). The rate of methylene blue adsorption on nanonetwork TiO2 was higher than that of non-templated (Supplementary Fig. S10d).

Discussion

Self-assembly of bioinspired peptide molecules forms isotropically distributed nanofibers providing a highly porous and homogenous three-dimensional nanonetwork as described in Figure 1. A peptide amphiphile (PA) molecule with a sequence of Lauryl-Val-Val-Ala-Gly-Lys-Dopa-Am (Dopa-PA) was designed and synthesized (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S2). A self-assembling peptide amphiphile is comprised of a hydrophobic alkyl group (lauryl) conjugated to a hydrophilic peptide segment32. Catechol group on Dopa residue is known to be critical for the mechanical strength of the initial hydrogel network, providing structural and surface stability during sample preparation and relatively high temperatures at ALD22. The majority of the reported template thicknesses for fibrous self-assembled peptide or polymer templates for mineral deposition are in the range of 20–100 nm5,9,21,33,34,35,36. Nanofibrous materials with a diameter of less than 10 nm, is rare (particularly for three-dimensional networks). The dimensions of the gel can be expanded to couple of centimeters in both height and diameter without destructing its homogeneity and forming macroscale cracks in the template network. In order to obtain a dry peptide network, solvent in the gel was removed by critical point drying, which had been proposed to be a reliable route to obtain undamaged dry peptide network of the gel37. It is imperative to maintain the porosity of the network without any degree of collapse, because our fabrication strategy depends on the delivery of gaseous precursors across the whole template through such nanoscale meshes to maximize the specific surface area. Well-preserved network structure showed Dopa-PA nanofibrous template can withstand temperatures up to 150°C without any structural damage on the supramolecular architecture33. The catechol groups on the peptide nanofibers undergo covalent crosslinking above pH 8.5, which strengthens the network against destabilizing factors22. The diameters of both TiO2 and ZnO nanonetworks were uniformly and precisely modulated by simply altering the total number of ALD cycles. The linear relationship was due to the constant deposition rate at each cycle. Angstrom level precision in each deposition cycle brings about powerful tunability over the nanotube diameter. TEM images of both TiO2 and ZnO nanotubes showed complete template coverage with homogenous deposition and high degree of coating conformity revealing the superiority of ALD for the fabrication of ultra-high-surface-area materials with three-dimensional structure (Fig. 4a, c and Supplementary Fig. S5). Slight deviation (10–15%) in the nanotube diameters of both TiO2 and ZnO was observed, possibly due to the formation of few Dopa-PA nanofiber bundles, which increased the core size of the inorganic nanotube. Less efficient diffusion of the precursor molecules into the centimeter scale network could contribute to the deviation. The growing inorganic thickness narrows the mesh size and hence the deviation from the average wall thickness increases (Supplementary Fig. S6). Nonetheless, to best of our knowledge, this uniformity is far superior to any wet-chemistry-involved protocol reported and thus represents a better alternative to the current methods.

Photoexcitation of TiO2 and ZnO semiconductor nanonetworks were characterized by monitoring decomposition of a model organic dye methylene blue (Supplementary Fig. S8) under UV irradiation. The specific surface area of the nanonetwork is inversely proportional to the wall thickness (or diameter of the nanotube) per unit mass. Therefore, decreasing the wall thickness is expected to increase the photoexcitation efficiency since higher number of hot spots per unit of mass becomes available for the reaction. The reduction in absorbance at photoexcitation wavelength decreases the number of photons absorbed by the nanotubes, which results in a reduction in the number of photogenerated electron-hole pairs formed for the same amount of photocatalyst. Therefore, for the present TiO2 and ZnO nanonetworks, we conclude that the observed optical changes play a major role in decreased photoexcitation efficiency below ~ 8 nm nanotube wall thickness, even though the total surface area per unit mass was increased. Consistent with our present findings, it was previously demonstrated that band gap energy of TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles increases with decreasing nanoparticle size due to the physical confinement of electrons and holes38,39,40. Through nanostructuring, excited-state electron-hole pairs' bulk recombination process becomes less dominant and redox potential difference between conduction-band electrons and valence-band holes increases due to the quantum confinement effect, which overall enhances the photocatalytic activity. However, when the nanostructure dimension is lowered below a certain limit, surface charge recombination process may become dominant and most of the electron-hole pairs generated sufficiently in the proximity of the surface undergo rapid quenching before the interfacial charge transfer process happens41. Additionally, due to quantum confinement effect at smaller nanometer dimensions, energy gap between valence band and conduction band states increases and only sufficiently high energy portion of the photons can initiate the catalytic activity38. Overall, these effects may significantly lower the photocatalytic performance of the nanostructures below a certain size limit. Based on the comparison with the nanoparticle-based semiconductor materials, we conclude that the optimal size in TiO2 and ZnO nanonetworks for photocatalytic efficiency may be caused by the wall thickness rather than the diameter of the nanotube42,43.

The sharp difference in photoexcitation properties of surface immobilized nanostructures and the flat surface was due to gained specific surface area through nanostructuring24. Both TiO2 and ZnO nanonetworks remained intact after the photoexcitation experiments. Surface-immobilized intact nanonetworks of TiO2 and ZnO ensured reusability of the photoactive surface, as well. In order to further study the advantage of nanostructuring on the photoexcitation efficiency, we next compared peptide nanofiber template-based synthesized anatase TiO2 nanonetwork to template-free solution-synthesized anatase TiO2. The accessible surface area was strikingly different between templated and non-templated anatase materials confirmed by higher physical adsorption kinetics and total adsorption of methylene blue on templated anatase TiO2 network (Supplementary Fig. S10d).

Overall, we demonstrate a facile and reliable fabrication method for TiO2 and ZnO semiconductor nanonetworks by using self-assembled peptide amphiphile nanofiber network as templates. Apart from the traditional organic templates in wet chemistry, we used a fully dried, three-dimensional (cm scale), highly interconnected supramolecular nanofibrous network template, which enabled ALD precursors to be homogenously deposited with exceptional conformity. The wall thickness of the inorganic nanotubes can be precisely controlled by simply altering the number of ALD cycles. Decrease in the wall thickness of both TiO2 and ZnO caused hypsochromic shift in UV absorbance. TiO2 and ZnO nanonetworks demonstrated superior photoexcitation properties compared to the unstructured TiO2 and ZnO substrates because of the enhanced surface area with nanostructured morphology. On the other hand, anatase TiO2 and hexagonal wurtzite ZnO nanonetworks are found to be dependent on both the wall thickness and total surface area per unit of mass. Importantly, immobilization of the semiconductor materials on a solid support enable recycling of the photoactive surface. Further studies can be extended to other transition metals and their compounds, such as oxides, nitrides and sulfides. As a result of the rapid and convenient scaling of the peptide nanofibers into macro-size networks, new opportunities could be available for fabrication of nanonetworks for a wider range of inorganic materials.

Methods

Materials

All reagents used in this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Merck, Fisher Scientific, ABCR, or Alfa-Aesar as analytical grade and were used without any further purification.

Synthesis and characterization of peptide amphiphile molecule

Fmoc solid phase peptide synthesis method was employed to synthesize Lauryl-Val-Val-Ala-Gly-Lys-Dopa-Am (Dopa-PA). Rink Amide MBHA resin (Novabiochem®) was used as the solid support. Carboxylate group activation of 2 mole equivalents (equiv.) of amino acids was succeeded by 1.95 mole equiv. of N,N,N',N'-Tetramethyl-O-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl) uronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) and 3 mole equiv. of diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) for 1 mole equiv. of functional sites on the solid resin. Fmoc groups were removed prior to each coupling step with 20% piperidine/dimethylformamide for 20 min. Amino acid coupling time was set to be 2 h at each cycle. Lauric acid was used as the source of lauryl group and its coupling mechanism was similar to amino acid coupling. After synthesis, all protecting groups were removed using a cleavage cocktail containing 95% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), 2.5% water and 2.5% triisopropylsilane. Excess TFA was removed by rotary evaporation followed by precipitation in diethyl ether overnight. The precipitate was collected and dissolved in ultra-pure water. This solution was frozen at −80°C followed by freeze-drying for one week. Residual TFA was removed by dissolving the whole batch in dilute HCl solution and freeze-drying. Small molecular contaminants and the remaining salts were removed through dialysis using a cellulose ester dialysis membrane with molecular-weight-cut-off of 100–500 Da. After dialysis, Dopa-PA molecules were once more freeze-dried and their purity was assessed using Agilent 6530 quadrupole time of flight (Q-TOF) mass spectrometry with electrospray ionization (ESI) source equipped with reverse-phase HPLC. Dopa-PA as synthesized and used with > 95% purity (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Template preparation

Template preparation procedure is schematically illustrated in Figure 1. To induce self-assembly, 1 wt% Dopa-PA solution (pH ~ 3) was casted onto the silicon wafer, which served as a solid support. The pH was then shifted to ~ 10, which triggered rapid gelation followed by covalent crosslinking of the peptide network (Fig. 1c). In order to prepare the ALD template, 1 wt% Dopa-PA hydrogel was formed in situ on a solid support (ca. 2 mm in height and ca. 0.8 cm in diameter). After 10–15 min incubation in a humidified environment, hydrogels were dehydrated with ethanol for critical point drying (Tourismis Autosamdri®-815B). Dried samples immobilized on the solid substrates were used for ALD.

Atomic layer deposition of TiO2 and ZnO

TiO2 and ZnO layers were deposited by ALD using Ti(NMe2)4, Et2Zn and H2O as titanium, zinc and oxygen precursors, respectively. Ti(NMe2)4 was preheated to 75°C and stabilized at this temperature prior to depositions. Depositions were carried out at 150°C in Savannah S100 ALD reactor (Cambridge Nanotech Inc.) using N2 as the carrier and purge gas. Exposure mode (a trademark of Cambridge Nanotech Inc.) was applied, in which dynamic vacuum was switched to static vacuum just before the precursor and oxidant pulses and switched back to dynamic vacuum before the purging periods after waiting for some time, i.e., exposure time. This special mode allowed time for precursor and oxidant molecules to diffuse into the highly porous, three-dimensional network of Dopa-PA nanofibers. N2 flow rate, which is normally 20 standard cubic centimeters per minute (sccm), was set to 10 sccm just before dynamic vacuum was switched to static vacuum. One growth cycle of TiO2 consisted of Ti(NMe2)4 pulse (0.1 s) and exposure (10 s), N2 purge (20 s), H2O pulse (0.015 s) and exposure (10 s) and N2 purge (20 s). TiO2 depositions were also carried out using tripled exposure and purge times, i.e., 30 s and 60 s, respectively. One growth cycle of ZnO consisted of Et2Zn pulse (0.015 s) and exposure (20 s), N2 purge (30 s), H2O pulse (0.015 s) and exposure (20 s) and N2 purge (30 s). Another set of ZnO depositions was carried out using tripled exposure and purge times, i.e., 60 s and 90 s, respectively, with no N2 flow after the first 30 s of exposure. For comparative purposes, TiO2 and ZnO films were deposited on solvent-cleaned, 5% HF-dipped Si wafers. Standard ALD mode was applied with the same precursor pulse and purge times used for the exposure mode. Growth rates of TiO2 and ZnO films at 150°C were measured by spectroscopic ellipsometry (V-VASE, J.A. Woollam Co.) as 0.51 Å/cycle and 1.53 Å/cycle, respectively.

Characterization of TiO2 and ZnO nanonetwork

The morphology and chemical composition of TiO2 and ZnO nanonetworks were characterized using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FEI Quanta 200 FEG) coupled with an energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer. Bare peptide networks were sputter coated with 5 nm gold/palladium prior to SEM imaging. TiO2 and ZnO deposited networks were investigated without any further coating. TEM and STEM images were acquired by using a FEI Tecnai G2 F30 TEM operating at 300 kV. To visualize Dopa-PA nanofibers, negative staining with uranyl acetate was performed. TiO2 and ZnO deposited nanofibers were visualized without any staining procedure. Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms at 77 K were measured on an Autosorb-iQwin™ automated gas sorption analyzer from Quantachrome® Instruments was employed. A PANalytical X'Pert Powder Diffractometer was used to reveal the crystal structure of TiO2 and ZnO nanonetworks. All data were recorded by using Cu Kα radiation in the range of 2θ = 20°–100° and with the spinning rate of 16 rpm in order to achieve homogenous data acquisition from samples. A thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA) (Q500, TA Instruments) was used to quantify the organic-inorganic composition of the ALD deposits. The temperature was ramped from 25 to 500 with 20°C min−1 heating rate in the presence N2. After 500°C, N2 was switched to O2 and heating was continued to 700°C with the same rate. A Thermo Scientific X-ray photoelectron spectrometer with Al Kα micro-focused monochromatic X-ray source and with ultra-high vacuum (~10-9) was utilized. The pH of Dopa-PA solution was prepared at pH ~ 3 and used immediately after it is dissolved in order to prevent spontaneous oxidation.

Photoexcitation reactions

Amorphous TiO2 was calcined to obtain anatase phase. For this, a gradient heating protocol (250°C for 1 h, 350°C for 30 min and 450°C for 30 min, sequentially) was applied, through which agglomeration of the nanostructures was prevented. To remove the peptide core, ZnO samples were calcined with the same protocol applied to the TiO2 samples. Photocatalytic reactions in Supplementary Figure S9 were carried out by immobilizing photocatalysts on silicon supports. Network-templated TiO2 and ZnO samples were prepared as shown in Figure 1 with 350 and 100 cycles, respectively. As a control of nanostructured material, silicon surfaces with the same projection area were coated with TiO2 and ZnO using ALD with 350 and 100 cycles, respectively. The photocatalyst surfaces were dipped into 2 × 10−5 M aqueous methylene blue solution and irradiated by 365 nm light source. UV-Vis spectrum of the dye was collected for 7 h with one or half-an-hour intervals using a spectrophotometer (Cary 5000, Varian). The reactions in Figure 6 were carried out using 0.87 mg templated anatase TiO2 and 0.87 mg non-templated, solution-synthesized anatase in 2 × 10−5 M of methylene blue aqueous solution. For this purpose 39.3 μL of 95% Ti(O-i-Pr)4 was added to 5 mL of pure ethanol and agitated by magnetic stirrer for 3 h. Solvent was removed and sample was calcined as described above. The photocatalysts used in this experiment were powdered in a mortar to obtain fine-grained particles. TEM images of the powdered nanonetworks were similar to Figure 4, Supplementary Figures S5 and S7. In order to test dye adsorption, samples were prepared similarly to photocatalytic experiment, only the test was carried out in the absence UV. As a result, decrease in the absorbance signal was attributed to physical adsorption of the dye molecules onto the photocatalyst surfaces. Samples of the photocatalytic reactions in Supplementary Figure S10 were prepared similar to shown in Figure 1 followed by calcination and powdering in a mortar prior to obtaining fine grained particles. 0.5 mg TiO2 and 1.1 mg ZnO were used in 2 × 10−5 M aqueous methylene blue solution irradiated by 365 nm light source.

References

Hwang, H. Y. et al. Emergent phenomena at oxide interfaces. Nat. Mater. 11, 103–113 (2012).

Adachi, M. M., Anantram, M. P. & Karim, K. S. Core-shell silicon nanowire solar cells. Sci. Rep. 3 (2013).

Luo, S.-C. et al. Polydioxythiophene Nanodots, Nonowires, Nano-Networks and Tubular Structures: The Effect of Functional Groups and Temperature in Template-Free Electropolymerization. ACS Nano 6, 3018–3026 (2012).

Roy, P., Berger, S. & Schmuki, P. TiO2 Nanotubes: Synthesis and Applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 2904–2939 (2011).

Acar, H., Garifullin, R. & Guler, M. O. Self-Assembled Template-Directed Synthesis of One-Dimensional Silica and Titania Nanostructures. Langmuir 27, 1079–1084 (2011).

Mahmoudi, M., Sant, S., Wang, B., Laurent, S. & Sen, T. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs): Development, surface modification and applications in chemotherapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 63, 24–46 (2011).

Lee, K. et al. Anodic Formation of Thick Anatase TiO2 Mesosponge Layers for High-Efficiency Photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 1478–1479 (2010).

Park, J.-H., Choi, H.-J., Choi, Y.-J., Sohn, S.-H. & Park, J.-G. Ultrawide ZnO nanosheets. J. Mater. Chem. 14, 35–36 (2004).

Khalily, M. A., Ustahuseyin, O., Garifullin, R., Genc, R. & Guler, M. O. A supramolecular peptide nanofiber templated Pd nanocatalyst for efficient Suzuki coupling reactions under aqueous conditions. Chem. Comm. 48, 11358–11360 (2012).

Herle, P. S., Ellis, B., Coombs, N. & Nazar, L. F. Nano-network electronic conduction in iron and nickel olivine phosphates. Nat. Mater. 3, 147–152 (2004).

Zhao, Y. & Gruner, G. Nanonet as a scaffold with targeted functionalities. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 24983–24991 (2012).

Zhuang, J. et al. Hierarchical porous TiO2@C hollow microspheres: one-pot synthesis and enhanced visible-light photocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 7036–7042 (2012).

Kim, S.-W. et al. Fabrication and Electrochemical Characterization of TiO2 Three-Dimensional Nanonetwork Based on Peptide Assembly. ACS Nano 3, 1085–1090 (2009).

Wang, X. et al. Effects of structural properties of electrospun TiO2 nanofiber meshes on their osteogenic potential. Acta Biomater. 8, 878–885 (2012).

Chiang, C. Y. et al. Formation of TiO2 nano-network on titanium surface increases the human cell growth. Dent. Mater. 25, 1022–1029 (2009).

Müllner, M., Lunkenbein, T., Miyajima, N., Breu, J. & Müller, A. H. E. A Facile Polymer Templating Route Toward High-Aspect-Ratio Crystalline Titania Nanostructures. Small 8, 2636–2640 (2012).

Bjursten, L. M. et al. Titanium dioxide nanotubes enhance bone bonding in vivo. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 92A, 1218–1224 (2010).

Kamegawa, T., Shimizu, Y. & Yamashita, H. Superhydrophobic Surfaces with Photocatalytic Self-Cleaning Properties by Nanocomposite Coating of TiO2 and Polytetrafluoroethylene. Adv. Mater. 24, 3697–3700 (2012).

Zhang, Q., Dandeneau, C. S., Zhou, X. & Cao, G. ZnO Nanostructures for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 21, 4087–4108 (2009).

Tong, H. et al. Nano-photocatalytic Materials: Possibilities and Challenges. Adv. Mater. 24, 229–251 (2012).

Acar, H. et al. Self-Assembled Peptide Nanofiber Templated One-Dimensional Gold Nanostructures Exhibiting Resistive Switching. Langmuir 28, 16347–16354 (2012).

Ceylan, H. et al. Mussel Inspired Dynamic Cross-Linking of Self-Healing Peptide Nanofiber Network. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 2081–2090 (2013).

Ceylan, H., Kocabey, S., Tekinay, A. B. & Guler, M. O. Surface-adhesive and osteogenic self-assembled peptide nanofibers for bioinspired functionalization of titanium surfaces. Soft Matter 8, 3929–3937 (2012).

Ceylan, H., Tekinay, A. B. & Guler, M. O. Selective adhesion and growth of vascular endothelial cells on bioactive peptide nanofiber functionalized stainless steel surface. Biomaterials 32, 8797–8805 (2011).

George, S. M. Atomic Layer Deposition: An Overview. Chem. Rev. 110, 111–131 (2009).

Knez, M., Nielsch, K. & Niinistö, L. Synthesis and Surface Engineering of Complex Nanostructures by Atomic Layer Deposition. Adv. Mater. 19, 3425–3438 (2007).

Greenlief, C. M., White, J. M., Ko, C. S. & Gorte, R. J. An XPS investigation of titanium dioxide thin films on polycrystalline platinum. J. Phys. Chem. 89, 5025–5028 (1985).

Kharlampieva, E. et al. Bioenabled Surface-Mediated Growth of Titania Nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 20, 3274–3279 (2008).

Mulligan, R. F., Iliadis, A. A. & Kofinas, P. Synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanostructures templated using diblock copolymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 89, 1058–1061 (2003).

Wu, K., Sun, Z. & Cui, J. Unique Approach toward ZnO Growth with Tunable Properties: Influence of Methanol in an Electrochemical Process. Crys. Growth Des. 12, 2864–2871 (2012).

Chen, X. & Mao, S. S. Titanium Dioxide Nanomaterials: Synthesis, Properties, Modifications and Applications. Chem. Rev. 107, 2891–2959 (2007).

Hartgerink, J. D., Beniash, E. & Stupp, S. I. Self-Assembly and Mineralization of Peptide-Amphiphile Nanofibers. Science 294, 1684–1688 (2001).

Knez, M. et al. Atomic Layer Deposition on Biological Macromolecules: Metal Oxide Coating of Tobacco Mosaic Virus and Ferritin. Nano Lett. 6, 1172–1177 (2006).

Korhonen, J. T. et al. Inorganic Hollow Nanotube Aerogels by Atomic Layer Deposition onto Native Nanocellulose Templates. ACS Nano 5, 1967–1974 (2011).

Han, T. H. et al. Highly entangled hollow TiO2 nanoribbons templating diphenylalanine assembly. J. Mater. Chem. 19, 3512–3516 (2009).

Sone, E. D., Zubarev, E. R. & Stupp, S. I. Semiconductor Nanohelices Templated by Supramolecular Ribbons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 1705–1709 (2002).

Scanlon, S. et al. Peptide aerogels comprising self-assembling nanofibrils. Micro Nano Lett. 2, 24–29 (2007).

Zhang, Z., Wang, C.-C., Zakaria, R. & Ying, J. Y. Role of Particle Size in Nanocrystalline TiO2-Based Photocatalysts. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 10871–10878 (1998).

Lin, K.-F., Cheng, H.-M., Hsu, H.-C., Lin, L.-J. & Hsieh, W.-F. Band gap variation of size-controlled ZnO quantum dots synthesized by sol–gel method. Chem. Phys. Lett. 409, 208–211 (2005).

Almquist, C. B. & Biswas, P. Role of Synthesis Method and Particle Size of Nanostructured TiO2 on Its Photoactivity. J. Catal. 212, 145–156 (2002).

Liu, J. et al. Self-Assembling TiO2 Nanorods on Large Graphene Oxide Sheets at a Two-Phase Interface and Their Anti-Recombination in Photocatalytic Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 20, 4175–4181 (2010).

Ishibashi, K.-I., Fujishima, A., Watanabe, T. & Hashimoto, K. Quantum yields of active oxidative species formed on TiO2 photocatalyst. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 134, 139–142 (2000).

Xiang, Q., Yu, J. & Wong, P. K. Quantitative characterization of hydroxyl radicals produced by various photocatalysts. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 357, 163–167 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK) grant numbers 110M353 and 112M578, FP7 Marie Curie IRG and COMSTECH-TWAS grants. H.C., R.G. and C.O.A. are supported by TUBITAK-BIDEB PhD fellowship. M.O.G. and A.B.T. acknowledge support from the Turkish Academy of Sciences Distinguished Young Scientist Award (TUBA-GEBIP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.C., C.O.-A., T.S.E., I.D., R.G., A.B.T., N.B. and M.O.G. were responsible in design and analysis of the experiments. H.C., C.O.-A., T.S.E., I.D. and R.G. performed all of the experiments. H.U. helped in analysis of the results. All authors wrote and reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

SUPPLEMENTARY INFO

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareALike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ceylan, H., Ozgit-Akgun, C., Erkal, T. et al. Size-controlled conformal nanofabrication of biotemplated three-dimensional TiO2 and ZnO nanonetworks. Sci Rep 3, 2306 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02306

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02306

This article is cited by

-

Heat flux localization and abnormal size effect induced by multi-body vibration in complex networks

Nonlinear Dynamics (2022)

-

Preparation and characterization of TiO2 based on wood templates

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Carbon/ZnO nanorods composites templated by TEMPO-oxidized cellulose and photocatalytic activity for dye degradation

Cellulose (2018)

-

Anatase-Titania Templated by Nanofibrillated Cellulose and Photocatalytic Degradation for Methyl Orange

Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.