Abstract

Objective:

To improve the management of obese adults (18–75 y) in primary care.

Design:

Cohort study.

Settings:

UK primary care.

Subjects:

Obese patients (body mass index ≥30 kg/m2) or BMI≥28 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidities in 80 general practices.

Intervention:

The model consists of four phases: (1) audit and project development, (2) practice training and support, (3) nurse-led patient intervention, and (4) evaluation. The intervention programme used evidence-based pathways, which included strategies to empower clinicians and patients. Weight Management Advisers who are specialist obesity dietitians facilitated programme implementation.

Main outcome measures:

Proportion of practices trained and recruiting patients, and weight change at 12 months.

Results:

By March 2004, 58 of the 62 (93.5%) intervention practices had been trained, 47 (75.8%) practices were active in implementing the model and 1549 patients had been recruited. At 12 months, 33% of patients achieved a clinically meaningful weight loss of 5% or more. A total of 49% of patients were classed as ‘completers’ in that they attended the requisite number of appointments in 3, 6 and 12 months. ‘Completers’ achieved more successful weight loss with 40% achieving a weight loss of 5% or more at 12 months.

Conclusion:

The Counterweight programme provides a promising model to improve the management of obesity in primary care.

Sponsorship:

Educational grant-in-aid from Roche Products Ltd.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Butler PM, Arnold MS, Fitzgerald JT & Feste CC (1995): Patient empowerment. Results of a randomised controlled trial. Diabetes Care 18, 943–949.

Bajekal M, Primatesta P & Prior G (eds) (2001): Health Survey for England. London: Department of Health, HMSO 2003.

Bourn J (2001): Tackling Obesity in England. Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General. London: National Audit Office.

Bramlage P, Wittchen HU, Pittrow D, Kirch W, Krause P, Lehnert H, Unger T, Hofler M, Kupper B, Dahm S & Sharma AM (2004): Recognition and management of overweight and obesity in primary care in Germany. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 28, 1299–1308.

Cade J & O'Connell S (1991): Management of weight problems and obesity: knowledge, attitudes and current practice of general practitioners. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 41, 147–150.

Cadman L & Findlay A (1998): Assessing practice nurses' change in nutrition knowledge following training from a primary care dietitian. J. R. Soc. Health 118, 206–209.

Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K & Thun MJ (2003): Overweight, obesity and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of US adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1625–1637.

Campbell K, Engel H, Timperio A, Cooper C & Crawford D (2000): Obesity management: Australian general practitioners’ attitudes and practices. Obes. Res. 8, 459–466.

Counterweight Project Team (2004a): Current approaches to obesity management in UK Primary Care: The Counterweight Programme. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet J. Hum. Nutr. Dietet. 17, 190–193.

Counterweight Project Team (2004b): A new evidence-based model for weight management in primary care: The Counterweight Programme. J. Hum. Nutr. Dietet. 17, 191–208.

Department of Health (2000): Coronary Heart Disease. National Service Framework, Chapter 2. London: UK Department of Health, March 2000.

Department of Health (2001): National Service Framework for Diabetes: Standards UK Department of Health, December 2001, Reference no. 26192.

Evans E (1999): Why should obesity be managed. The obese individual's perspective. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 23 (Suppl 4), S3–S5.

Foster GD, Wadden TA, Makris AP, Davidson D, Swain Sanderson R, Allison DB & Kessler A (2003): Primary care physicians’ attitudes about obesity and its treatment. Obes. Res. 11, 1168–1177.

Frijling BD, Lobo CM, Hulscher ME, Akkermans RP, van Drenth BB, Prins A, van der Wouden JC & Grol RP (2003): Intensive support to improve clinical decision making in cardiovascular care: a randomised controlled trial in general practice. Qual. Saf. Health Care 12, 181–187.

Galuska DA, Will JC, Serdula MK & Ford ES (1999): Are health care professionals advising obese patients to lose weight? JAMA 282, 1576–1578.

Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, Mowatt G, Fraser C, Ber L, Grili R, Harvey E, Oxman A & O'brien MA (2001): Changing provider behaviour: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med. Care 39 (Suppl 2), 22–45.

Hiddink GJ, Hautvast JG, van Woerkum CM, Fieren CJ & Van’t Hof MA (1997): Consumer's expectations about nutrition guidance: the importance of primary care physicians. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 65 (Suppl), 1974S–1979S.

Hoppe R & Ogden J (1997): Practice nurses' beliefs about obesity and weight related interventions in primary care. Int. J. Obes. 21, 141–146.

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM & Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group (2002): Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 393–403.

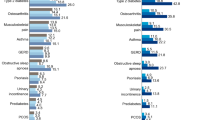

Laws R, Reckless J & on behalf of the Counterweight Project Team (2003): Differences in disease prevalence between obese and normal weight individuals. Int. J. Obes. 27 (Suppl 1), S83.

Lean ME, Han TS & Seidell JC (1999): Impairment of health and quality of life using new US federal guidelines for the identification of obesity. Arch. Intern. Med. 159, 837–843.

Levy BT & Williamson PS (1998): Patient perceptions and weight loss of obese adults. J. Fam. Pract. 27, 285–290.

Margolis PA, Lannon CM, Stuart JM, Fried BJ, Keyes-Elstein L & Moore Jr DE (2004): Practice based education to improve delivery systems for prevention in primary care: randomised trial. BMJ 328, 388.

Moore H, Greenwood D, Gill T, Waine C, Soutter J & Adamson A (2003a): A cluster randomised trial to evaluate a nutrition training programme. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 53, 271–277.

Moore H, Summerbell CD, Greenwood DC, Tovey P, Griffiths J, Henderson M, Hesketh K, Wollgar S & Adamson AJ (2003b): Improving the management of obesity in primary care: cluster randomised trial. BMJ 327, 1085–1088.

Murphee D (1994): Patient attitudes toward physician treatment of obesity. J. Fam. Pract. 38, 45–48.

Must A, Spadano J, Coakley E, Field A, Colditz G & Dietz W (1999): The disease burden associated with obesity. JAMA 282, 1523–1529.

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (1998): The Practical Guide. Identification, Evaluation and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. USA: National Institute of Health.

Ogrinc G, Headrick LA, Mutha S, Coleman MT, O’Donnell J & Miles PV (2003): A framework for teaching medical students and residents about practice-based learning and improvement, synthesized from a literature review. Acad. Med. 78, 748–756.

Ouschan R, Sweeney JC & Johnson LW (2000): Dimensions of patient empowerment: Implications for professional services marketing. Health Mark Q. 18, 99–114.

Pibernik-Okanovic M, Prasek M, Poljicanin-Filipovic T, Pavlic-Renar I & Metelko Z (2004): Effects of an empowerment-based psychosocial intervention on quality of life and metabolic control in type 2 diabetic patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 52, 193–199.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC & Norcross JC (1992): In search of how people change. Am. Psychol. 47, 1102–1114.

Reckless JPD & on behalf of the Counterweight Project Team (2003): Knowledge, attitudes and confidence of general practitioners and practice nurses in lifestyle management. Diabetic Med. 20 (Suppl 2), 77.

Richmond R, Kehoe L, Heather N, Wodak A & Webster I (1996): General practitioner's promotion of healthy lifestyles: what patients think. Aust. NZ J. Pub. Health 20, 195–200.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (1996): Obesity in Scotland: Integrating Prevention with Weight Management. Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegial Guidelines Network.

Simkin-Silverman LR, Gleason KA, King WC, Weissfeld LA, Buhari A, Boraz MA & Wing RR (2005): Predictors of weight control advice in primary care practices: patient health and psychosocial characteristics. Prev. Med. 40, 71–82.

Stafford RS, Farhat JH, Misra B & Schoenfeld DA (2000): National patterns of physician activities related to obesity management. Arch. Fam. Med. 9, 631–638.

The Counterweight Project Team (2004c): The influence of body mass index on number of visits to general practitioners in the UK. Int. J. Obes. 28 (Suppl 1), S116.

The Counterweight Project Team (2005): The impact of obesity on drug prescribing in primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. (in press).

The Royal College of Physicians London (2003): Anti-Obesity Drugs Guidance on Appropriate Prescribing and Management. London: RCP.

Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hamalainen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, Laakso M, Louheranta A, Rastas M, Salminen V, Uusitupa M & Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group (2001): Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 1343–1349.

Wadden TA, Anderson DA, Foster GD, Bennett A, Steinberg C & Sarwer DB (2000): Obese women's perceptions of their physicians’ weight management attitudes and practices. Arch. Fam. Med. 9, 854–860.

Wallace PG & Haines AP (1984): General practitioners and health promotion: what patients think. BMJ 289, 534–536.

Wallace PG, Brennan PJ & Haines AP (1987): Are general practitioners doing enough to promote healthy lifestyle. Findings from the Medical Research Council's general practice research framework study on lifestyle and health. BMJ 294, 940–942.

Welschen I, Kuyvenhoven MM, Hoes AW & Verheij TJ (2004): Effectiveness of a multiple intervention to reduce antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract symptoms in primary care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 329, 431.

Wing RR & Hill JO (2001): Successful weight loss maintenance. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 21, 323–341.

Wollard J, Burke V, Beilin LJ, Verheijden M & Bulsara MK (2003): Effects of a general practice-based intervention on diet, body mass index and blood lipids in patients at cardiovascular risk. J. Cardiovasc. Risk 10, 31–40.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participating practices for their enthusiasm and cooperation. The Counterweight Project was funded by an Educational grant-in-aid to the Project Board from Roche Products Ltd. We thank Dr J Wilding and Professor A Barnett who participated in the initial discussions that led to the Counterweight Programme and Mr A Basar for participation during the early stages of the programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Additional information

Guarantor: RA Laws.

Contributors: The principal investigators, WMAs and National Coordinator form the Counterweight Project team. The principle investigators were responsible for study design and directed the programme. The WMAs contributed to study design, conducted practice audit and facilitated implementation of counterweight programme, coordinated by the National Coordinator. RL wrote the first draft of this paper. All authors reviewed and contributed to the final manuscript.

M McQuigg1, J Brown1, J Broom1, RA Laws2,12*, JPD Reckless3, PA Noble4, S Kumar5, EL McCombie6, MEJ Lean6, GF Lyons7, GS Frost7, MF Quinn8, JH Barth8, SM Haynes9, N Finer9, HM Ross10 and DJ Hole111Clinical Research Unit, Grampian University Hospitals Trust, Aberdeen, UK;2Nutrition and Dietetic Service, Royal United Hospital, Bath, UK;3University of Bath, Royal United Hospital, Bath, UK;4University Hospitals Coventry, Warwick NHS Trust, Birmingham, UK;5Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Birmingham, UK;6Department of Human Nutrition, Glasgow Royal Infirmary, Glasgow, UK;7Nutrition & Dietetic Research Group, Hammersmith Hospitals NHS Trust, Hammersmith, UK;8Leeds General Infirmary, Leeds NHS Trust, Leeds, UK;9Centre for Obesity Research, Luton and Dunstable Hospital NHS Trust, Luton, UK;10Roche Products Ltd, Welwyn Garden City, UK; and11Public Health and Health Policy, Division of Community Based Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK12Has written the paper with contribution from other authors. All authors belong to the Counterweight Project Team. The names are in alphabetical order according to centre.

Funding:

Educational grant-in-aid from Roche Products Ltd.

Intellectual property rights reside with the Counterweight Project Team.

Competing Interest:

MSAM3, JB2,3, RAL3, JPDR1,3, PN3, SK12,3, ELMcC3, MEJL1,2,3,4, GFL3, GSF5, MSQ3, JHB1,2,3,4, SMG3, NF1,2,3,4, HMR3, 6 declare potential competing interests:

Here 1,2,3,4,5,6 represent:

1Acted as consultants.

2Have received lecture honoraria.

3Have attended national/international meetings as guests of Roche Products Ltd.

4Involvement as above with other pharmaceutical companies with an interest in obesity.

5Research grant.

6HMR is employed by Roche Products Ltd, but reports to the Counterweight Project Board.

Discussion after Laws

Brug: This was impressive. You showed in a structured way what behaviour change strategies you used in different parts of your programme. Would you also have had other differences between the dropouts and the people who stayed in the programme? Because you could of course argue that staying in the programme resulted in higher weight loss, but you could also say that higher weight loss resulted in staying in the programme.

Laws: The only variables relating to completion of the programme were age, practice social deprivation and baseline BMI. We found a greater proportion of older individuals completed the programme along with those who attended a GP practice in a more affluent area and those with a higher baseline BMI. In terms of weight loss we have found that non diabetics and those with impaired glucose tolerance lose more weight than those with diabetes. Also the number of appointments the patient attends is correlated with weight loss. So again it comes back to social support.

Kok: How is the current motivation of the persons who were in this trial? Are they in a continuous change mood or mode? The patients; they lost 5 kg or something like that; are they motivated to continue trying to lose weight?

Laws: That is probably something I will be able to address in the qualitative study that we are adding on to the intervention. In this study, we want to find out with the patients what their experience with the programme was. We have the idea that the successful patients were motivated to have more appointments, and also the nurses wanted to see them more, because the success also was reinforcing for the nurses. But it is not yet clear whether people come back more often because they are successful or whether they have success because they come back more often.

Kok: Your scientific objective is clear. What is the policy objective in the long run? Is this something that may be applied on a national scale?

Laws: We are looking at the final results this year; we are going to do a health economic analysis, look at cost-effectiveness. Also bear in mind that the practices that became part of this programme actually volunteered to cooperate, so we probably are dealing with a more motivated group of practices. We need to look at this to find out whether it is applicable on a larger scale. This is one of the reasons we are doing the qualitative studies as well. But certainly we have had discussions with the UK Department of Health.

Rosser: Have you done any analysis of the practices that dropped out? Do you have any preliminary information about that?

Laws: We have only got feedback information from a few practices. We heard from a practice that a nurse left and the next nurse who came on board was not willing to take on the project.

Truswell: You said that one out of six were a success so far, with 5% weight loss. But the others, they were partly a success, weren’t they?

Laws: Absolutely. We found that three-quarters of patients were losing some weight at 12 months; and bearing in mind that the average BMI for this group was 37, it certainly was difficult for the patients.

Truswell: And you may have stopped an even larger percentage from continuing to put on more weight.

Laws: Yes, but unfortunately with this type of design, we did not have a comparable control group.

Mathus-Vliegen: Do you know how much patients went through the second phase when more active treatment was provided.

Laws: About 22% had more active treatment. And there were some patients going to dieticians and exercise groups.

Mathus-Vliegen: So no one went for surgery?

Laws: No. Interestingly, none of these patients were referred to special obesity centres, which is surprising. Maybe this is because a lack of these centres and long waiting times.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

The Counterweight Project Team. Empowering primary care to tackle the obesity epidemic: the Counterweight Programme. Eur J Clin Nutr 59 (Suppl 1), S93–S101 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602180

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602180

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A brief intervention for weight control based on habit-formation theory delivered through primary care: results from a randomised controlled trial

International Journal of Obesity (2017)

-

Research protocol: Management of obesity in patients with low health literacy in primary health care

BMC Obesity (2015)

-

Éducation thérapeutique et parcours de soins de la personne obèse

Obésité (2014)

-

A randomised controlled trial to compare a range of commercial or primary care led weight reduction programmes with a minimal intervention control for weight loss in obesity: the Lighten Up trial

BMC Public Health (2010)

-

Empowering family doctors and patients in nutrition communication

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2005)