Abstract

Background:

The key mediator of new vessel formation in cancer and other diseases is VEGF-A. VEGF-A exists as alternatively spliced isoforms - the pro-angiogenic VEGFxxx family generated by exon 8 proximal splicing, and a sister family, termed VEGFxxxb, exemplified by VEGF165b, generated by distal splicing of exon 8. However, it is unknown whether this anti-angiogenic property of VEGF165b is a general property of the VEGFxxxb family of isoforms.

Methods:

The mRNA and protein expression of VEGF121b was studied in human tissue. The effect of VEGF121b was analysed by saturation binding to VEGF receptors, endothelial migration, apoptosis, xenograft tumour growth, pre-retinal neovascularisation and imaging of biodistribution in tumour-bearing mice with radioactive VEGF121b.

Results:

The existence of VEGF121b was confirmed in normal human tissues. VEGF121b binds both VEGF receptors with similar affinity as other VEGF isoforms, but inhibits endothelial cell migration and is cytoprotective to endothelial cells through VEGFR-2 activation. Administration of VEGF121b normalised retinal vasculature by reducing both angiogenesis and ischaemia. VEGF121b reduced the growth of xenografted human colon tumours in association with reduced microvascular density, and an intravenous bolus of VEGF121b is taken up into colon tumour xenografts.

Conclusion:

Here we identify a second member of the family, VEGF121b, with similar properties to those of VEGF165b, and underline the importance of the six amino acids of exon 8b in the anti-angiogenic activity of the VEGFxxxb isoforms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

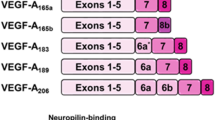

The advent of anti-neovascular therapies in cancer and eye disease has prompted a burgeoning interest in the mechanisms behind the initiation, development and refinement of new vessel formation. The growth of new vessels from those already established is termed angiogenesis and although a complex process, involving over 50 growth factors, cytokines, receptors and enzymes, is dominated, in most situations, by the 38 kDa cysteine-knot protein vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Following the initial identification of VEGF (Senger et al, 1983) many splice isoforms were subsequently identified, eventually forming a family of mature peptides – the VEGFxxx family (see Figure 1) (Houck et al, 1991). The individual family members have different expression patterns (e.g., VEGF183 expression is mostly restricted to the eye (Jingjing et al, 1999), VEGF145 in the reproductive system (Charnock-Jones et al, 1993)); unique characteristics with respect to heparin and receptor-binding properties (resulting from inclusion/exclusion of particular exon segments) and are named by amino acid size. Despite this heterogeneity they are all considered pro-angiogenic, pro-permeability vasodilators. The evidence for these properties for individual splice isoform recombinant proteins in vivo, however, varies from conclusive (VEGF165) (Leung et al, 1989), through mixed (VEGF121) (Keyt et al, 1996; Zhang et al, 2000) and scanty (VEGF145) (Poltorak et al, 1997) to absent (VEGF206).

Alternative splicing of VEGF-A generating VEGFxxx and VEGFxxxb isoforms. (A) VEGF-A contains eight exons with receptor binding found in exons 3 and 4, heparin and neuropilin binding in exons 6 and 7 and 8a. (B) Alternative splicing of the C-terminal end using proximal splice site generating VEGFxxx isoforms or distal splice site generating VEGFxxxb isoforms. This splicing leads to an alterative last six amino acids (CDKPRR or SLTRKD). (C) The C-terminal splicing leads to the possibility of two sister families of VEGF-A isoforms; VEGFxxx and VEGFxxxb, differing only in the C-terminal.

In addition, it has now become evident that even the presence of six splice isoforms is an over-simplification. The pro-angiogenic potential of conventional VEGF isoforms is thought to result from the C-terminus (Keyt et al, 1996), more specifically the six amino acids of exon 8a – CDKPRR (Cebe Suarez et al, 2006; Cebe-Suarez et al, 2008). A sister family of splice isoforms has now been identified (see Figure 1) in which the pro-angiogenic domain (exon 8a) is replaced by the six amino acids coded for by exon 8b – SLTRKD. These exon 8b isoforms (VEGFxxxb) are exemplified by the only isoform so far extensively investigated, VEGF165b. VEGF165b has radically different properties to that of the widely studied VEGF165. We, and others have shown that VEGF165b is not pro-angiogenic in vivo (Woolard et al, 2004) and specifically and actively inhibits VEGF165-mediated endothelial cell proliferation and migration in vitro (Bates et al, 2002; Rennel et al, 2008a, 2008b), vasodilatation ex vivo (Bates et al, 2002) and in vivo angiogenesis assays such as rabbit corneal eye pocket, chicken chorioallantoic membrane, mesenteric and Matrigel implants (Woolard et al, 2004; Cebe Suarez et al, 2006; Kawamura et al, 2008). Furthermore, VEGF165b not only inhibits physiological angiogenesis in developing mammary tissue in transgenic animals over-expressing VEGF165b (Qiu et al, 2008) but also pathological angiogenesis in models of the proliferative ocular lesions of diabetes (retinopathy of pre-maturity) (Konopatskaya et al, 2006) and age-related macular degeneration (laser-induced choroidal neovascularisation, Hua et al, unpublished) and in six different tumour models in vivo (Woolard et al, 2004; Varey et al, 2008; Rennel et al, 2008a, 2008b). The above anti-angiogenic properties occur when delivered as VEGF165b-transfected cells (Woolard et al, 2004; Varey et al, 2008; Rennel et al, 2008a), VEGF165b-adenoviral constructs (Woolard et al, 2004) or recombinant human protein (Konopatskaya et al, 2006; Rennel et al, 2008b).

Although a significant amount of evidence on the expression and function of the VEGF165b isoform has already been published, there is very little evidence on other VEGFxxxb family members, and their existence and activity is still uncertain. This study, therefore, investigates the properties of a second member of the VEGFxxxb family – the peptide VEGF121b, addressing the hypothesis that VEGF121b will also show anti-angiogenic properties. We present descriptive expression data and functional data on cell migration, receptor binding and in vivo tumour and ocular angiogenesis in vivo.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

Paired colon samples were from partial colon resection for carcinoma. Samples were obtained by taking biopsies of the fresh specimen from a non-necrotic central portion of the tumour and from a peripheral part of the macroscopically normal colon (n=15). The mean patient age was 71.5 (58–80) years, with 62% males and Duke's staging as follows: 6.7% A, 46.7% B and 46.7% C. Informed consent for obtaining the tissue was gained in compliance with local ethics committee approval.

PCR on cDNA from human total RNA

Total RNA was extracted from human tissue using TRIZOL (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) (Chomczynski, 1993) and treated with DNase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Complementary DNA was made using oligo dT primers or 3′UTR primer (GCTCTAGAAGCAGGTGAGAGTAAGCG) as described earlier (Bates et al, 2002). PCR was used to identify presence of VEGF121b, VEGF165 and VEGF165b using specific primers; VEGF165/VEGF165b exon 7 GGCAGCTTGAGTTAAACGAACG, 3′UTR ATGGATCCGTATCAGTCTTTCCTGG, VEGF121b exon 5/8b GAAAAATCTCTCACCAGGAAA, 3′UTR II CTGGATTAAGGACTGTTCTG, VEGF121 exon 5/8a GAAAAATGTGACAAGCCGAG 3′UTR II CTGGATTAAGGACTGTTCTG, GAPDH forward TGATGACATCAAGAAGGTGGTGAAG, reverse TCCTTGGAGGCCATGTGGGCCAT and PCR products were separated and visualised using 4% agarose/ethidium bromide gel. Putative VEGF121b PCR products were purified using QIAquick gel extraction (Qiagen, Crawley, UK) and inserted into pGEM vector and confirmed by sequencing of plasmid.

Production of recombinant protein

Recombinant human VEGF121b (VEGF121b) and VEGF165b were produced in Chinese hamster ovary cells as glycosylated dimers by Cancer Research Technologies (London, UK) as described earlier (Rennel et al, 2008b). VEGF165 and VEGF121 were from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA.

In vitro assays with human umbilical vein endothelial cells

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were extracted from umbilical cords from caesarean sections (St Michael's Hospital, Bristol, UK). HUVEC migration was performed as described earlier (Rennel et al, 2008b). Briefly, HUVECs were serum starved for 6 h and 100 000 serum-starved cells were plated into collagen-coated 8 μm inserts (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) placed in 24-well plates with 500 μl of chemoattractant in M200 medium with 0.1% v/v FCS and 0.2% w/v BSA and incubated overnight at 37°C to allow for migration. Migrating cells were stained in Mayer's haematoxylin. Migrating cells were counted (10 random fields per insert) and expressed as percentage of migrating cells in relation to the total number of seeded cells. Experiments were performed in triplicates. A peptide (Ac-SLTRKD) was generated and increasing concentrations (1 nM–100 μ M) peptide was combined with or without 1 nM VEGF165 to analyse impact on HUVEC migration.

Cell cytotoxicity was performed using a lactate dehydrogenase assay (Promega); 13 000 cells were seeded in cell culture 96-well plates in triplicates or quadruplicates in 100 μl of full growth media (FGM) for 24 h. Recombinant VEGF protein was added in 100 μl media with 0.1% FCS for 48 h. Conditioned media and lysed cells were spun at 250 g for 15 min at 4°C followed by addition of kit components, incubated for 30 min and read at 490 nm. Receptor and kinase inhibitors were added at indicated concentrations with or without 1.4 nM VEGF121b.

For direct counting, HUVECs were seeded in 24-well plates in triplicates in FGM 24 h followed by 48 h exposure to 1.4 nM growth factors or FGM. Cells were trypsinised and counted using a haemocytometer.

In vivo tumour model

LS174t human colon carcinoma cell lines (ECACC, Salisbury, UK) (Yuan et al, 1996; Lee et al, 2000) were grown in Minimum Essential Eagle’s Medium supplemented with 10% v/v FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine and 1% non-essential amino acids (all from Sigma Aldrich, Gillingham, UK). Cells were transfected with 1 μg/well of pcDNA3 empty vector or pcDNA3-VEGF121b, using lipofectamine plus (Invitrogen) as per manufacturer's instructions and selected using 500 μg ml−1 geneticin (Sigma Aldrich). Conditioned media and cell lysate were analysed by western blotting to confirm expression levels of VEGF isoforms. Two million cells were injected subcutaneously into the lumbar region of nude mice (six per group). Xenotransplanted tumours were measured by calliper every 2–3 days and tumour volume was calculated according to (length × width × [length+width]/2). Mice were culled by cervical dislocation and tumours were removed when the first tumour reached 16 mm in any direction all mice were killed in that group. Injections, measurements and analysis were all carried out with the investigators blinded to group.

Tumour vessel density was counted in 10 random fields in haematoxylin and eosin stained 6 μm sections frozen sections from tumours. Vessel presence was confirmed by staining by blocking in 5% v/v goat Ig for 30 min, 20 μg ml−1 biotinylated isolectin B4 (L-2140 Sigma-Aldrich) or 1 μg ml−1 Flk-1 (sc-6251, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) overnight, 2 μg ml−1 anti-mouse biotin antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 1 h followed by avidin biotinylated enzyme complex (Vector Laboratories) for 30 min followed by DAB substrate (Vector Laboratories). Sections were examined using a Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope and photos were captured using Nikon Eclipse Net software. To visualise apoptosis, tumour sections were stained with cleaved caspase 3 antibody (1 : 400 dilution, CatNo9661 Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) and positive staining areas were circled and compared to total tumour area using Image J software.

Cell proliferation by flow cytometry analysis and direct counting

Trypsinised LS174t cells were fixed in 70% ethanol for 30 min at 4 °C followed by 100 μg ml−1 ribonuclease (Sigma Aldrich) for 5 min. Propidium iodine (PI, 50 μg ml−1) was added to the cells and analysed by flow cytometer.

For healthy, apoptotic and necrotic cell determination a PI-annexin V-FITC kit was used (Bender MedSystems, Vienna, Austria). Cell culture media was centrifuged at 1500 r.p.m. to collect non-adherent cells, added to trypsined cells and diluted in binding buffer to approximately 300 000 cells/ml. Cells were stained with 25 μl annexin V-FITC for 10 min, washed, stained with 20 μg ml−1 PI and analysed by flow cytometer.

For direct counting, 135 000 LS174t cells/24 well was seeded out in triplicates in media supplemented with 0.1% FCS in the presence or absence of 1 nM VEGF121b. Cells were trypsined and counted using a haemocytometer after 24 and 48 h.

In vivo imaging of 125I-VEGF165b biodistribution

Nude mice were injected with LS174t tumours on the right hindleg. 125I-VEGF121b was generated using Iodogen tubes (Pierce Biotechnology, Cramlington, UK) and purified with NAP-10 columns (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St Giles, UK). Analysis by thin layer chromatography showed >95% purity (125I-VEGF121b/total 125I). Approximalty 3.2 MBq (70 μg protein) was injected into the tail vein when tumours were >10 mm in diameter. Anaesthesia was maintained by 2% halothane during X-ray and scanning (NanoSPECT/CT, Bioscan, Washington, DC, USA), after 40, 70, 120, 240 or 1440 min. For biodistribution studies, 0.10 MBq (3 μg) 125I-VEGF121b was injected into the tail vein and mice were culled at 120 or 240 min. Organs and tissues of interest were excised and assessed using a gamma counter (LKB Wallac 1282 Compugamma CS, Wallac, Perkin Elmer, MA, USA). Uptake was expressed as % injected dose/g tissue.

In vitro saturation binding of 125I-VEGFxxxb to Fc-VEGFR-1

One μg ml−1 human VEGFR-1-Fc chimaera or VEGFR-2-Fc (R&D Systems) was bound to Immulon II HB Flat 96-well plates (Thermo Labsystems, Basingstoke, UK) overnight followed by blocking with 3% w/v BSA for 2 h and binding of 125I-rhVEGF121b or 125I-rhVEGF165b for 4 h in 1% w/v BSA in triplicates. Plates were washed three times with PBS+0.05% v/v Tween in between each step. To detach the complex 10% w/v SDS was added and counted in a gamma counter. Data were calculated as c.p.m. and expressed as % binding compared with maximum binding concentration.

SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting of tissue and cell lysate

Tissue lysates from transfected cells or human colon tissue were extracted using RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1% v/v NP-40, 0.25% w/v Na-deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg ml−1 of each of aprotinin, pepstatin and leupeptin) and homogenised using a polytron and spun at 12 000 r.p.m. for 10 min at 4°C. Lysates were separated on 15% SDS–PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes, blocked in 10% w/v dry milk, incubated with a mouse monoclonal anti-human VEGFxxxb antibody (2 μg ml−1, R&D Systems) for 1 h followed by horse radish peroxidase conjugated anti-mouse antibody (1/5000, Pierce Biotechnology) for 1 h. Membranes were developed using supersensitive West Femto Maximum Sensitive Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology). Densitometry analysis of western blots was performed using Image J. VEGF121b is detected by immunoblotting using anti-VEGF antibodies (A-20 Santa Cruz or AF-293 R&D Systems) and the commercial VEGFxxxb antibody (A56/1, R&D Systems, cat no. MAB3045). Commercial ELISA for VEGF165b (R&D Systems) and panVEGF (Duoset R&D Systems) can pick up VEGF121b but panVEGF ELISA underestimates the VEGF121b levels (and VEGF165b) by approximately 40% (Varey et al, 2008).

Oxygen-induced retinopathy mouse model

The oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) model was performed as described earlier (Smith et al, 1994; Konopatskaya et al, 2006) with minor modifications. Neonatal C57/Bl6 mice and nursing CD1 dams were exposed to 75% oxygen between P7 and P12. Return to room air induced hypoxia in the ischaemic areas. On P13, mice received either VEGF121b (1 or 10 ng) or Hank's buffered solution in 1 μl intraocular injections using a Nanofil syringe fitted with a 35 gauge needle (WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA) into the left eye under isoflurane anaesthesia. On P17, both eyes were dissected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 4 h at 4°C and retinas were dissected. Retinas were permeabilised in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and 1% bovine serum albumin, stained with 20 μg ml−1 biotinylated isolectin B4 (Sigma Aldrich) in PBS pH 6.8, 1% Triton-X100, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM MgCl2, followed by 20 μg ml−1 ALEXA 488-streptavidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) and flat mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories). Quantification of neovascular and ischaemic areas were performed in a blinded fashion using Photoshop CS3 along with Image J and expressed as percentage of total retinal area (=normal+ischaemic+neovascular).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 4.0cx). Data are given as means±s.e.m. or means±95 % confidence interval when stated. One-way ANOVA was used to compare migration, cytoprotection, tumour growth and retinal vascularisation. T-test was used to compare tumour growth, apoptosis and microvascular density and paired t-test used for retinal areas.

Results

Expression of VEGF121b in human colon tissue and its reduction in colon carcinoma

Earlier, we reported a shift in expression of VEGFxxxb isoforms in human malignant melanoma (Pritchard-Jones et al, 2007), prostate (Woolard et al, 2004; Rennel et al, 2008a) and colon carcinoma (Varey et al, 2008) leading to less anti-angiogenic VEGFxxxb splice isoforms in cancer tissue. The ELISA used to quantify the levels of VEGFxxxb isoforms does not distinguish between the individual members of the VEGFxxxb isoform family. Earlier RT–PCR used to detect VEGFxxxb isoforms (using exon 7 and 3′UTR primers) did not detect VEGF121b (see Figure 2A) as the forward primer was in exon 7 (spliced out in VEGF121b and VEGF121). To identify VEGF121b, mRNA primers were used that spanned the exon 5/exon 8b boundary. These primers detected VEGF121b but not VEGF165b or VEGF165 (see Figure 2B). VEGF121b was detected in normal tissue such as aorta, spleen, placenta and some normal and tumour colon tissue (see Figure 2B), which also expressed VEGF165 and VEGF165b (see Figure 2A) and retina and vitreous (Figure 2C). Presence of VEGF121b was confirmed by sequencing of PCR products.

VEGF121b is expressed in human tissue and the expression is reduced in human colon tumours. (A–C) PCR on cDNA from different human tissues using primers to detect VEGF121b, VEGF165b and VEGF165. VEGF165 and VEGF165b are detected in colon cDNA both in tumour and adjacent control colon (A). VEGF121b is detected in colon tissue, aorta, spleen and placenta using VEGF121b-specific primers (B). VEGF121, 165, 121b and 165b can be found in the retina and to a lesser extent in the human vitreous (C). (D) Densitometry analysis of VEGF121b and VEGF165b protein expression in matched human control colon samples and colon tumours analysed by western blot using a VEGFxxxb-specific antibody (n=14 pairs, P=0.0067 paired t-test).

Measurement of VEGF levels in an earlier study on human colon carcinoma showed that the angiogenic VEGF isoforms were upregulated compared with matched colon tissue whereas the levels of anti-angiogenic VEGFxxxb isoforms remained unchanged. Western blot on that tissue showed two bands consistent with expression of VEGF121b and VEGF165b (Varey et al, 2008). Quantification of the western blot analysis of paired human colon tissues from tumour and adjacent normal colon tissue indicates a downregulation of VEGF121b in tumour tissue compared to VEGF165b (see Figure 2D, P<0.01 paired t-test, n=14 pairs).

VEGF121b is secreted, inhibits migration and reduces apoptosis in endothelial cells

To determine whether VEGF121b can be secreted by colon cells, VEGF121b recombinant cDNA was transfected into colon carcinoma cells. Western blotting of the lysate and the media showed that VEGF121b was found pre-dominantly in the media, indicating that it is freely secreted (see Figure 3A), in contrast to cells that were not transfected with the VEGF121b plasmid, in which no VEGF121b was seen in the media or the lysate. VEGF121b binding to VEGFR-1 was analysed by incubating increasing concentrations of radiolabelled VEGF121b with immobilised VEGFR-1 (see Figure 3B). The saturation-binding kinetics of VEGF121b (see Figure 3B, log10EC50=−9.9±0.04) was similar to that for VEGF165b measured at the same time (EC50=−9.65±0.04, Figure 3C).

VEGF121b inhibits migration of endothelial cells and inhibits serum starved induced cell death in endothelial cells through classical VEGFR-induced pathways. (A) VEGF121b is found in the media on transfected cancer cells. (B–C) VEGF121b has similar saturation binding kinetics to VEGFR-1 as VEGF165b. (D–E) VEGF121b inhibits VEGF165 (D) or VEGF121 (E) induced migration of HUVEC. Cells were allowed to migrate through 8 μm pore inserts with increasing concentrations of VEGF121b (0–6 nM) or VEGF165b (0–2.5 nM) in the presence of 1 nM VEGF165 or 2.9 nM VEGF121. Data plotted as percentage migration compared to total number of seeded cells (F) VEGF121b is cytoprotective to a similar degree as VEGF165 in HUVEC. Release of lactate dehydrogenase as a measurement of cell viability was monitored after 48 h of serum starvation in the presence of increasing amounts of VEGF121b (0–3.6 nM), 1 nM VEGF165 or full growth media (FGM) with serum and growth factors. (G) Similar cytoprotection of VEGF121b was observed in serum starved HUVEC as cell number was not reduced by the same amount after 48 h of cell starvation. (H) VEGF121b cytoprotection is mediated via VEGFR-1 and -2, P13-K, MEK1/2. Inhibition of VEGFR1/2=200 nM PTK787, VEGFR-2=10 nM ZM323881, P13- K=15 μM LY294002, p38=10 μ M SB203580 and MEK1/2=15 μ M PD98059. (One-way ANOVA, Dunnett's post hoc test, 0 nM or control vs addition, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001).

We have shown earlier that VEGF165b conditioned media (Bates et al, 2002; Rennel et al, 2008a) or recombinant human VEGF165b (Woolard et al, 2004; Rennel et al, 2008b) inhibits VEGF165-induced migration of endothelial cells. Migration of HUVEC was inhibited by the addition of VEGF121b either when stimulated with VEGF165 (see Figure 3D, VEGF165 vs any treatment P<0.05) or VEGF121 (see Figure 3E, VEGF121 vs any treatment P<0.05). The level of inhibition was similar to that observed with VEGF165b (see Figure 3D) and no additional significant reduction in migration was observed with the combination of VEGF121b and VEGF165b (see Figure 3D). Addition of up to 100 μ M peptide of the last six amino acids had no effect on VEGF165-induced HUVEC migration (data not shown) indicating that the 3D structure and or the full length of the VEGFxxxb protein is needed for inhibition.

VEGF165 is known to protect endothelial cells from apoptosis and incubation of HUVECs with recombinant VEGF121b was equally cytoprotective (see Figure 3F, no addition vs any treatment P<0.01). This resulted in a small increase in cell number induced by treatment with VEGF121b (see Figure 3G). To determine the mechanism of this cytoprotective effect of VEGF121b, HUVECs were treated with inhibitors of receptor tyrosine kinases and signalling kinases (see Figure 3H). Inhibition of VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 by 100 nM PTK787 resulted in an inhibition of the cytoprotective effect of VEGF121b, as did incubation with the VEGFR-2-specific antagonist ZM323881 (10 nM). The cytoprotective effect was blocked by inhibitors of PI3Kinase (LY294002) and MEK1/2 (PD98059), but not by inhibitors of p38 MAPK (SB203580, see Figure 3H).

Over-expression of VEGF121b reduces tumour growth through a direct effect on endothelial cells

We have shown earlier that over-expression of VEGF165b reduces tumour growth in five different tumour types (Woolard et al, 2004; Varey et al, 2008; Rennel et al, 2008a), but VEGF165b does not directly affect proliferation or apoptosis of LS174t cells (Varey et al, 2008). To verify whether VEGF121b could inhibit tumour growth as well, LS174t colon carcinoma tumour cells were transfected with plasmid containing VEGF121b or cloning vector alone (control). Expression levels were confirmed by immunoblot on lysate and conditioned media showing that VEGF121b was secreted and found in the media (see Figure 3A). Cells were injected into the back of nude mice and tumour growth was monitored over time. VEGF121b reduced tumour growth compared with empty vector (290±66 mm3 vs 925±268 mm3 after 14 days, P<0.05, unpaired t-test Welch correction, see Figure 4A). VEGF121b tumours were smaller and excised tumours were less haemorrhagic than those with empty vector (see Figure 4A inserted images). Immunohistochemical staining was performed to visualise blood vessel distribution (see Figure 4B for representative VEGFR-2 staining). Analysis of the vessel density in 10 random fields in each tumour showed a decreased number of vessels in VEGF121b tumours (control vs VEGF121b, 3.5±0.6 vs 1.7±0.1, P<0.05 unpaired t-test n=6 tumours per treatment 10 fields analysed per tumour, Figure 4B). VEGFR-2 staining of tumour sections showed expression of VEGFR-2 in the tumour vessels and not in the general tumour mass (see Figure 4B inserted images) indicating an effect of VEGF121b on the endothelium rather than an anti-proliferative effect on the tumour cells. Earlier analysis has shown absence of VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 expression in LS174t cells (Rennel et al, 2008b). To determine whether VEGF121b expression induced apoptosis in the tumour cells, tumours were stained for cleaved caspase 3. There was no change in caspase staining in control vs VEGF121b-expressing tumours (see Figure 4C).

VEGF121b reduces tumour growth in nude mice bearing colon carcinoma tumours by reducing tumour vessel ingrowth. (A) LS174t human colon carcinoma cells were transfected with pcDNA3-VEGF121b or empty pcDNA3 plasmid and injected subcutaneously into nude mice and tumour growth was monitored over time. Over-expression of VEGF121b resulted in a reduced tumour growth and contained less blood compared with control cells (inserted images). Scale bar=10 mm. (B) Immunohistochemistry staining of tumour sections for VEGFR-2 visualise microvessels (inserted images). Quantification of microvascular density showed significantly fewer blood vessels per unit area than control tumours. Each point represents the mean of 10 random analysed fields and six tumours per treatment were examined (*P<0.05 unpaired t-test). (C) Cleaved caspase 3 staining of tumour sections (inserted images) showed no significant difference in apoptosis. (D, E) VEGF121b has no effect on LS174t colon carcinoma growth in vitro. Over-expression of VEGF121b in LS174t colon carcinoma cells had no effect on cell proliferation analysed by FACS (D). Addition of 1 nM VEGF121b had no effect of cell number analysed by direct counting of cells over 48 h (E).

Transfected LS174t colon cells were analysed by flow cytometry and VEGF121b had no effect on proliferation (see Figure 4D control vs VEGF121b, S/G2-M 21±2.3 vs 27±4.4, P=0.36 unpaired t-test). In addition, addition of recombinant VEGF121b had no effect on tumour cell number (see Figure 4F). These data indicate that VEGF121b reduced tumour growth by reducing the tumour-driven angiogenesis, rather than a direct effect on the tumour cells themselves.

Biodistribution of intravenous VEGF121b

The results above indicate that VEGF121b could be a potential therapeutic agent in angiogenic diseases, if the uptake into neovascular tissues was sufficient. To determine how intravenously (i.v.) injected recombinant VEGF121b is distributed in vivo, 125I-VEGF121b was injected i.v. into tumour-bearing mice and imaged using high-resolution single photon emission computed tomography (NanoSPECT/CT). Radiolabelled VEGF121b was distributed quickly through the mouse and images acquired at 40 min post injection (p.i.) showed accumulation in organs of metabolism and secretion. Thereafter, the overall signal gradually declined because of excretion/degradation of the radiolabelled protein. Figure 5A shows whole body images at different time p.i. Uptake of radioactivity can be seen in the tumour as well as abdominal tissues such as stomach and kidney. Coronal and sagittal sections also visualised uptake in the tumour at 2 h p.i. (see Figure 5E-F). Biodistribution of tissue and tumour indicated that approximately 2.5% of the total 125I is found in the tumour at 2 h and stays at a similar level for up to 24 h (see Figure 5G). Intestine and liver showed high uptake with a maximum at 4 h. No obvious adverse haemodynamic effects were seen in the animals.

In vivo distribution of 125I-VEGF121b in tumour-bearing mice. Tumour-bearing mice received an intravenous injection of 125I-VEGF121b and 3D imaged using NanoSPECT/CT. (A–D) Time course for biodistribution of 125I-VEGF121b after tail vein injection using transverse sections. (E) Coronal. (F) Para-sagittal through the centre of the tumour. The tumour is circled and arrows indicate different organs. (G) Quantification uptake into different organs and tissues over time. Data expressed as % in tissue relative to the total injected dose, per gram of tissue.

VEGF121b rescues retinal vasculature by reducing neovascularisation and ischaemia

We have shown earlier that the anti-angiogenic VEGF165b can inhibit retinal neovascularisation in an OIR mouse model when administered as a single intraocular injection (Konopatskaya et al, 2006). In this model retinal vaso-obliteration occurs in the central retina when pups are exposed to high oxygen (from P7 to P12) and when returned to room air the relative hypoxia induces neovascularisation with a peak reached at P17. Retinas were flat mounted and stained with isolectin to visualise vessels with neovascularisation occurring at the edge of the central ischaemic area (see Figure 6A). Blind quantification of the injected and uninjected contralateral retina, showed reduced neovascularisation after 1 or 10 ng VEGF121b (see Figure 6B-C, uninjected control vs 1 or 10 ng VEGF121b P<0.05 or control injection vs 1 or 10 ng VEGF121b P<0.05). Injection of 10 ng VEGF121b reduced the ischaemic area, and increased the area of normal vasculature (see Figure 6D-E, control injection vs 10 ng VEGF121b P<0.05 for ischaemic and normal vessel growth). The overall result was an increase in the proportion of normal vasculature in these retinae (see Figure 6E). Injection of control solution had no effect compared with contralateral eye (see Figure 6B uninjected control vs control injected eye, P>0.05, paired t-test).

VEGF121b reduces hypoxia-induced retinal neovascularisation after single intraocular injection. The oxygen-induced retinopathy mouse model leads to neovascularisation induced by hypoxia. (A) Flat mounted mouse retinas with vessels visualised by isolectin staining. Ischaemic and neovascularised areas are circled (i, ischaemic, n, neovascular and r, normal retinal vessels). Normal retinal vessels (vii) are slender compared to neovascular vessels (viii). (B) Quantification of neovascularisation, ischaemic and normal vessel growth compared to matched uninjected control eye (paired t-test, *P<0.05, **P<0.01). (C–E). Distribution of ischaemic, neovascular and normal vessel growth in injected retinas relative to uninjected eye showed that VEGF121b reduced neovascularisation (C) and the ischaemic areas (D) leading to an increase in the revascularisation (E). (One-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post hoc test, ΔP<0.05, ΔΔP<0.01 compared to vehicle injected=0 ng).

Discussion

The existence of a second family of VEGF isoforms with overtly different properties from that of the conventional VEGF species required a radical re-evaluation of VEGF biology, not only academically – thousands of manuscripts have attempted to quantify ‘VEGF’ in body fluids or tissues using primers, probes or antibodies that would not distinguish these contrasting families; but also in terms of the pathogenesis of disease and the potential clinical importance of VEGFxxx/VEGFxxxb balance, because these families derive from the same gene. VEGF165b is widely expressed (Bates et al, 2002, 2006; Cui et al, 2004; Perrin et al, 2005; Pritchard-Jones et al, 2007; Varey et al, 2008) and may form the pre-dominant isoform in many tissues (Perrin et al, 2005; Varey et al, 2008). The physiological role of these isoforms is only just now being elucidated in normal tissues, and it seems that they act as a brake on excess angiogenesis during conditions of controlled growth or VEGFxxx expression. Examples include development of the ovary, where the VEGFxxxb levels are maintained to prevent angiogenesis into the developing germ bud and so prevent formation of a testicular artery (VEGFxxxb antibodies are angiogenic in this model, Artac et al, in press), in the virgin mammary fat pad, where VEGFxxx levels are prevented from inducing angiogenesis until lacteal formation, when VEGFxxxb levels fall (and prevention of this fall results in reduced milk production) (Qiu et al, 2008), and in the eye where a relative drop in VEGFxxxb levels is accompanied with angiogenesis in the retina in diabetes (Perrin et al, 2005). Increased VEGFxxxb levels also seem to be required for normal pregnancy, as a failure to upregulate VEGFxxxb in first trimester pregnancies is associated with subsequent maternal–fetal pathology (Bills et al, 2009).

The development of an angiogenic milieu within a stable and non-angiogenic tissue, may depend to some degree on changes in gene (over) transcription or suppression but also on changes in mRNA splicing control. The control of splicing between the two VEGF isoform families has begun to be elucidated, and it has been shown that multiple stimulatory signals can differentially affect the choice of splice site in the terminal exon, including hypoxia (Varey et al, 2008), IGF, TNF and PDGF (Nowak et al, 2008), which all favour proximal splice site selection in exon 8, and hence angiogenic isoforms, and the latter three growth factors suppress distal splicing, whereas hypoxia seems not to affect it. TGF-β, on the other hand, seems to favour distally spliced isoforms (Nowak et al, 2008). This seems to be through mechanisms involving splice factors such as ASF/SF2 and SRp55. Additionally, alteration of splicing has been seen in human and animal models of disease including in Denys Drash Syndrome (Schumacher et al, 2007), kidney, prostate and colon cancer (Bates et al, 2002; Woolard et al, 2004; Varey et al, 2008; Rennel et al, 2008a), malignant melanoma (Pritchard-Jones et al, 2007) where the PSS is favoured and animal models of glaucoma where the DSS is favoured (Ergorul et al, 2008). However, there is very little known about regulation of splice site choice in the terminal exon from the exon 5 splice donor site, but the earlier studies on hypoxia indicate that this is unlikely to be a regulatory factor for VEGF121b.

The most studied VEGFxxxb family member – VEGF165b – has been clearly shown not to be angiogenic. Other researchers have shown that the six amino acids of exon 8b are required for the anti-angiogenic activity of VEGF165b because artificially generated VEGF159 lacking both exons 8a and b, which is not angiogenic (Cebe Suarez et al, 2006). Exon 8a seems to be required for heparin and neuropilin-1 binding and full activation of the VEGFR-1 and -2, as it is likely to interfere with the correct folding and 3D structure of the protein, resulting in differential activation of VEGFR-2 tyrosine phosphorylation, and hence downstream signalling (Cebe Suarez et al, 2006; Cebe-Suarez et al, 2008; Kawamura et al, 2008). Here, we present for the first time new data suggesting that the presence of exon 8b in a different VEGFxxxb family member endows it with similar properties to VEGF165b: VEGF121b inhibits experimental endothelial cell migration in vitro and new vessel formation in vivo in tumour and non-tumour-related angiogenesis. The VEGFxxxb family members seem to share similar properties.

We have shown that VEGF121b has similar bio-distribution after i.v. injection to VEGF165b and a similar proportion of injected bolus reaching a single implanted tumour – with around 2% for VEGF121b and 6% for VEGF165b (Rennel et al, 2008b). Furthermore, we have shown in this study and in our earlier work (Woolard et al, 2004) that these two VEGFxxxb family members bind the conventional tyrosine kinase VEGF receptors. VEGF165b does not bind neuropilin-1 (Kawamura et al, 2008), and there is evidence that VEGF121 also binds neuropilin poorly, suggesting that VEGF121b would not bind it either. von Wronski et al (2007) have highlighted the likelihood that neuropilin-1 binds the residues coded for by exon 8a and replacement by 8b results in VEGF isoforms that do not seem to show neuropilin-1 binding (Cebe Suarez et al, 2006).

Although we have shown that VEGF165b and VEGF121b bind to the conventional VEGF receptors, further work will be required to investigate the mechanistic differences between VEGF121b and its corresponding isoform VEGF121. Studies into the mechanistic contrast between VEGF165b and VEGF165 are more advanced with increasing evidence now emerging that VEGF165b, although binding to VEGFR-2 with equal affinity as VEGF165, is not simply a classical competitive inhibitor. VEGF165b does stimulate the phosphorylation of VEGFR-2 but qualitatively in a unique way. Although VEGF165b does lead to the phosphorylation of tyrosine residues of the VEGF receptor, tryptic phosphopeptide mapping and the use of phosphosite-specific antibodies have shown that VEGF165b is considerably poorer than VEGF165 in inducing phosphorylation of the angiogenic positive regulatory site Y1052 (Y1054 in human sequence) in VEGFR-2 (Kawamura et al, 2008). This study also confirmed that the ability of different VEGF isoforms to induce angiogenesis correlated with their abilities to bind the VEGF co-receptor neuropilin-1 (Kawamura et al, 2008). Whether or not VEGF121b activates VEGFR-2 in a similar way is yet to be investigated, as are the potential effects of simultaneous VEGF121b and VEGF165b administration of receptor activity, angiogenesis or tumour growth.

Another significant finding here is that VEGF121b seems to act as a survival factor for human endothelial cells. This activity seems to be VEGFR dependent, and uses classical survival pathways such as the PI3 kinase and MEK/ERK pathways. This provides a potential explanation for the surprising finding that the ischaemic region in the retinal neovascular preparations was reduced by VEGF121b administration. This is of particular interest as it suggests a vascular normalisation in the retina, leading to the possibility that VEGF121b may be of use in ischaemic retinal diseases associated with angiogenesis such as diabetic retinopathy.

In summary, we provide new information about the existence, expression and activity of a second member of the anti-angiogenic VEGFxxxb family. Our data confirm that VEGF121b has similar inhibitory properties on the process of in vivo angiogenesis and the components of angiogenesis in vitro as does VEGF165b, supporting the notion that the replacement of the terminal six amino acids with those coded for by exon 8b is of crucial importance in converting the dominant pro-angiogenic growth factor into a positively anti-angiogenic molecule that may have broad therapeutic potential. Further studies will be required to elucidate its mechanism of action of VEGF121b and its potential clinical value along with its other family member VEGF165b.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Artac RA, McFee RM, Longfellow Smith RA, Baltes-Breitwisch MM, Clopton DT, Cupp AS (in press) Neutralization of vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitory isoforms is more effective than treatment with angiogenic isoforms in stimulating vascular development and follicle progression in the perinatal rat ovary. Biol Reprod

Bates DO, Cui TG, Doughty JM, Winkler M, Sugiono M, Shields JD, Peat D, Gillatt D, Harper SJ (2002) VEGF165b, an inhibitory splice variant of vascular endothelial growth factor, is down-regulated in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 62: 4123–4131

Bates DO, MacMillan PP, Manjaly JG, Qiu Y, Hudson SJ, Bevan HS, Hunter AJ, Soothill PW, Read M, Donaldson LF, Harper SJ (2006) The endogenous anti-angiogenic family of splice variants of VEGF, VEGFxxxb, are down-regulated in pre-eclamptic placentae at term. Clin Sci (Lond) 110: 575–585

Bills VL, Varet J, Millar A, Harper SJ, Soothill PW, Bates DO (2009) Failure to up-regulate VEGF165b in maternal plasma is a first trimester predictive marker for pre-eclampsia. Clin Sci (Lond) 116: 265–272

Cebe-Suarez S, Grunewald FS, Jaussi R, Li X, Claesson-Welsh L, Spillmann D, Mercer AA, Prota AE, Ballmer-Hofer K (2008) Orf virus VEGF-E NZ2 promotes paracellular NRP-1/VEGFR-2 coreceptor assembly via the peptide RPPR. FASEB J 22: 3078–3086

Cebe Suarez S, Pieren M, Cariolato L, Arn S, Hoffmann U, Bogucki A, Manlius C, Wood J, Ballmer-Hofer K (2006) A VEGF-A splice variant defective for heparan sulfate and neuropilin-1 binding shows attenuated signaling through VEGFR-2. Cell Mol Life Sci 63: 2067–2077

Charnock-Jones DS, Sharkey AM, Rajput-Williams J, Burch D, Schofield JP, Fountain SA, Boocock CA, Smith SK (1993) Identification and localization of alternately spliced mRNAs for vascular endothelial growth factor in human uterus and estrogen regulation in endometrial carcinoma cell lines. Biol Reprod 48: 1120–1128

Chomczynski P (1993) A reagent for the single-step simultaneous isolation of RNA, DNA and proteins from cell and tissue samples. Biotechniques 15: 532–534, 536-7

Cui TG, Foster RR, Saleem M, Mathieson PW, Gillatt DA, Bates DO, Harper SJ (2004) Differentiated human podocytes endogenously express an inhibitory isoform of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF165b) mRNA and protein. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F767–F773

Ergorul C, Ray A, Huang W, Darland D, Luo ZK, Grosskreutz CL (2008) Levels of vascular endothelial growth factor-A165b (VEGF-A165b) are elevated in experimental glaucoma. Mol Vis 14: 1517–1524

Houck KA, Ferrara N, Winer J, Cachianes G, Li B, Leung DW (1991) The vascular endothelial growth factor family: identification of a fourth molecular species and characterization of alternative splicing of RNA. Mol Endocrinol 5: 1806–1814

Jingjing L, Xue Y, Agarwal N, Roque RS (1999) Human Muller cells express VEGF183, a novel spliced variant of vascular endothelial growth factor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 40: 752–759

Kawamura H, Li X, Harper SJ, Bates DO, Claesson-Welsh L (2008) Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A165b is a weak in vitro agonist for VEGF receptor-2 due to lack of coreceptor binding and deficient regulation of kinase activity. Cancer Res 68: 4683–4692

Keyt BA, Berleau LT, Nguyen HV, Chen H, Heinsohn H, Vandlen R, Ferrara N (1996) The carboxyl-terminal domain (111-165) of vascular endothelial growth factor is critical for its mitogenic potency. J Biol Chem 271: 7788–7795

Konopatskaya O, Churchill AJ, Harper SJ, Bates DO, Gardiner TA (2006) VEGF165b, an endogenous C-terminal splice variant of VEGF, inhibits retinal neovascularization in mice. Mol Vis 12: 626–632

Lee CG, Heijn M, di Tomaso E, Griffon-Etienne G, Ancukiewicz M, Koike C, Park KR, Ferrara N, Jain RK, Suit HD, Boucher Y (2000) Anti-Vascular endothelial growth factor treatment augments tumor radiation response under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. Cancer Res 60: 5565–5570

Leung DW, Cachianes G, Kuang WJ, Goeddel DV, Ferrara N (1989) Vascular endothelial growth factor is a secreted angiogenic mitogen. Science 246: 1306–1309

Nowak DG, Woolard J, Amin EM, Konopatskaya O, Saleem MA, Churchill AJ, Ladomery MR, Harper SJ, Bates DO (2008) Expression of pro- and anti-angiogenic isoforms of VEGF is differentially regulated by splicing and growth factors. J Cell Sci 121: 3487–3495

Perrin RM, Konopatskaya O, Qiu Y, Harper S, Bates DO, Churchill AJ (2005) Diabetic retinopathy is associated with a switch in splicing from anti- to pro-angiogenic isoforms of vascular endothelial growth factor. Diabetologia 48: 2422–2427

Poltorak Z, Cohen T, Sivan R, Kandelis Y, Spira G, Vlodavsky I, Keshet E, Neufeld G (1997) VEGF145, a secreted vascular endothelial growth factor isoform that binds to extracellular matrix. J Biol Chem 272: 7151–7158

Pritchard-Jones RO, Dunn DB, Qiu Y, Varey AH, Orlando A, Rigby H, Harper SJ, Bates DO (2007) Expression of VEGF(xxx)b, the inhibitory isoforms of VEGF, in malignant melanoma. Br J Cancer 97: 223–230

Qiu Y, Bevan H, Weeraperuma S, Wratting D, Murphy D, Neal CR, Bates DO, Harper SJ (2008) Mammary alveolar development during lactation is inhibited by the endogenous antiangiogenic growth factor isoform, VEGF165b. FASEB J 22: 1104–1112

Rennel E, Waine E, Guan H, Schuler Y, Leenders W, Woolard J, Sugiono M, Gillatt D, Kleinerman E, Bates D, Harper S (2008a) The endogenous anti-angiogenic VEGF isoform, VEGF165b inhibits human tumour growth in mice. Br J Cancer 98: 1250–1257

Rennel ES, Hamdollah-Zadeh MA, Wheatley ER, Magnussen A, Schuler Y, Kelly SP, Finucane C, Ellison D, Cebe-Suarez S, Ballmer-Hofer K, Mather S, Stewart L, Bates DO, Harper SJ (2008b) Recombinant human VEGF165b protein is an effective anti-cancer agent in mice. Eur J Cancer 44: 1883–1894

Schumacher VA, Jeruschke S, Eitner F, Becker JU, Pitschke G, Ince Y, Miner JH, Leuschner I, Engers R, Everding AS, Bulla M, Royer-Pokora B (2007) Impaired glomerular maturation and lack of VEGF165b in Denys-Drash syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 719–729

Senger DR, Galli SJ, Dvorak AM, Perruzzi CA, Harvey VS, Dvorak HF (1983) Tumor cells secrete a vascular permeability factor that promotes accumulation of ascites fluid. Science (NY) 219: 983–985

Smith LE, Wesolowski E, McLellan A, Kostyk SK, D′Amato R, Sullivan R, D’Amore PA (1994) Oxygen-induced retinopathy in the mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 35: 101–111

Varey AH, Rennel ES, Qiu Y, Bevan HS, Perrin RM, Raffy S, Dixon AR, Paraskeva C, Zaccheo O, Hassan AB, Harper SJ, Bates DO (2008) VEGF 165 b, an antiangiogenic VEGF-A isoform, binds and inhibits bevacizumab treatment in experimental colorectal carcinoma: balance of pro- and antiangiogenic VEGF-A isoforms has implications for therapy. Br J Cancer 98: 1366–1379

von Wronski MA, Tweedle MF, Nunn AD (2007) Binding of the C-terminal amino acids of VEGF121 directly with neuropilin-1 should be considered. FASEB J 21: 1292; author reply 1293

Woolard J, Wang WY, Bevan HS, Qiu Y, Morbidelli L, Pritchard-Jones RO, Cui TG, Sugiono M, Waine E, Perrin R, Foster R, Digby-Bell J, Shields JD, Whittles CE, Mushens RE, Gillatt DA, Ziche M, Harper SJ, Bates DO (2004) VEGF165b, an inhibitory vascular endothelial growth factor splice variant: mechanism of action, in vivo effect on angiogenesis and endogenous protein expression. Cancer Res 64: 7822–7835

Yuan F, Chen Y, Dellian M, Safabakhsh N, Ferrara N, Jain RK (1996) Time-dependent vascular regression and permeability changes in established human tumor xenografts induced by an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 14765–14770

Zhang HT, Scott PA, Morbidelli L, Peak S, Moore J, Turley H, Harris AL, Ziche M, Bicknell R (2000) The 121 amino acid isoform of vascular endothelial growth factor is more strongly tumorigenic than other splice variants in vivo. Br J Cancer 83: 63–68

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Cancer Research UK Development Grant A5047 (ER), Cancer Research UK C18064/A5730 (AHRV), National Kidney Research Fund Grant R15/2/2003 and British Heart Foundation Grants BB2000003 and BS06/005 (DOB). This work was also in part supported by The Prostate Cancer Research Foundation and the NBHT Specific Cancer Research Projects Fund. The authors would like to thank Cancer Research Technologies, London, for generation of VEGF121b, Joanne Malcolm for technical help and extraction of HUVEC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Conflict of interest

Professor Bates and Dr Harper are co-inventors on the patent describing VEGF165b as a potential therapeutic in cancer. There are no other conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Rennel, E., Varey, A., Churchill, A. et al. VEGF121b, a new member of the VEGFxxxb family of VEGF-A splice isoforms, inhibits neovascularisation and tumour growth in vivo. Br J Cancer 101, 1183–1193 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605249

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605249

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

How VEGF-A and its splice variants affect breast cancer development – clinical implications

Cellular Oncology (2022)

-

(Intrinsically disordered) splice variants in the proteome: implications for novel drug discovery

Genes & Genomics (2016)

-

New prospects in the roles of the C-terminal domains of VEGF-A and their cooperation for ligand binding, cellular signaling and vessels formation

Angiogenesis (2013)

-

Assessing the in vivo efficacy of biologic antiangiogenic therapies

Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology (2013)

-

Effects of exogenous VEGF165b on invasion and migration of human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells

Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology [Medical Sciences] (2011)