Key Points

This paper:

-

Improves the understanding of the disadvantages of water fluoridation.

-

Demonstrates public perceptions of dental discolouration typical of dental fluorosis.

-

Shows in one step the application of public participation and involvement in health service research by gathering the public's views on a health issue.

-

Provides findings that will assist policy makers to settle the issue of water fluoridation in the United Kingdom.

Abstract

Objectives A cross-sectional national survey to explore perceptions of dental fluorosis and to determine the proportion of people regarding fluorosis as aesthetically objectionable at differing levels of defect.

Methods A survey using a multistage stratified random probability sample of 6,000 UK adult households. Face-to-face interviews were carried out using a structured questionnaire and photographs of different levels of dental fluorosis. Respondents were interviewed about the parameters of satisfaction, attractiveness and need for treatment for dental fluorosis.

Results The proportion of respondents perceiving teeth as unattractive, unsatisfactory and requiring treatment increased with increasing severity of dental fluorosis. Using agreement between the three negative perceptions as a measure, 14% of the sample perceived mild dental fluorosis as aesthetically objectionable, 45% at moderate level and 91% at severe levels.

Conclusion Negative perceptions of dental fluorosis were lower than reported previously. Three parameters were included in the approach to estimate aesthetically objectionable fluorosis which may provide a more realistic measure than those used previously. The nature of the index and the sample included suggest that findings of this survey provide a reasonable indicator of the likely impact of water fluoridation. Findings may have important implications for fluoridation policies in the United Kingdom and elsewhere.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The image of a perfect smile represented by regularly arranged white teeth has gained in popularity in recent decades and it has become important to have teeth with no sign of abnormality.1,2 The growth of this expectation may reflect the rising values placed on aesthetics by prosperous Western societies. Whatever the reasons for change, these revised values mean that possible negative aesthetic outcomes of national polices such as water fluoridation require evaluation.

While the evidence for the effectiveness of fluoride in the reduction of dental caries seems clear,3 adverse effects, particularly on tooth colour, may also have an impact since fluorosis affects people's appearance. Results of previous studies have demonstrated that dental fluorosis may cause dissatisfaction and feelings of unattractiveness or more general negative lay perceptions. At least one study has suggested that it may have an impact on well-being.4

Fluoride intake, particularly from drinking water, is associated with a risk of developing dental fluorosis. The risk is high when fluoride concentration exceeds recommended optimal levels. Even an optimal intake of fluoride may result in very mild to mild dental fluorosis.3,5

Severe levels of dental fluorosis are widely perceived as aesthetically objectionable by both professionals and the public.6,7,8,9,10 However perceptions of mild and moderate levels remain controversial. The findings from studies of perceptions of fluorosis have varied widely. It is difficult to extrapolate findings regarding fluorosis of aesthetic concern because of different study methodologies and variations in selection of the age and characteristics of study subjects. Researchers have shown that children, adults, lay groups and professionals have differing perceptions of dental fluorosis.6,8 Current health agendas are moving towards empowering people and planning services to meet professional and individual expectations. In this context, in the United Kingdom, where less than 10% of the country is currently fluoridated but where other sources of fluoride are widely available, clear understanding of the likely public impact of expanding water fluoridation is essential. The aims of this study are therefore to explore the current perception of dental fluorosis nationally and to determine the level of aesthetic objection to each level of fluorosis.

Material and methods

The vehicle for this study was the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Omnibus Survey (2001) in the UK. The sampling frame for the Omnibus Surveys is the entire Postcode Address File (PAF). A stratified random probability sampling technique was applied. At the first stage 100 postal sectors were selected. At the second stage, 30 addresses were randomly selected from within each postal sector. At the final stage, one adult aged 16 years or over was selected randomly for interview at each eligible address. The survey procedure was run twice in two consecutive months. Of the 6,000 addresses selected 5,504 were eligible for visits, the remainder (496) being unoccupied buildings or business postcodes.

Sixteen trained interviewers from ONS carried out the survey through face-to-face interviews. Seven pictures representing different levels of dental fluorosis (mild, moderate and severe) categorised using the TF index11 were shown randomly to the study participants. Three pairs of pictures were included on the card, each pair representing one of the three severity levels of fluorosis and a seventh picture represented normal teeth. The pair used to denote mild fluorosis were those showing TF scores of 1 and 2, moderate level those with TF scores 3 and 4, and severe level TF score 5 and above. Perception of dissatisfaction and unattractiveness were recorded on a five-point scale while responses to questions of perceived treatment need were recorded on a three point scale (definite need, not sure, no need). The questions related to the three domains were as follows:

-

How attractive do you find the teeth shown on the photograph?

-

Would you be satisfied if your teeth had the same colour?

-

Do you think that dental treatment is needed in this case?

Responses to perception of attractiveness and satisfaction were amalgamated each into three response groups; satisfied, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, and dissatisfied; and attractive, neither attractive nor unattractive, and unattractive respectively.

Data analysis

Data were coded and entered onto computer at ONS and were subsequently analysed using the SPSS statistical package. The response rate to the survey was calculated and descriptive analysis of perception of attractiveness, satisfaction and perceived treatment need was carried out. A case was considered as aesthetically objectionable fluorosis when there was agreement on the negative perceptions for the three domains (ie when the case was considered by the respondent as unattractive, a cause for dissatisfaction and requiring treatment).

Results

Of the 5,504 addresses eligible to take part in the study, there was a failure to make contact in 549 cases (10%) and people at 2,020 (39%) declined to take part. People were successfully interviewed at 3,384 addresses, the response rate from the initial 6,000 selected addresses was therefore 61% (3,384) and of eligible addresses it was 69%. Characteristics of the study group are summarised in Table 1. Subjects included men and women (with slightly more of the latter) and ranged in age between 16 to over 55. Twenty-two per cent of those taking part were educated at least to degree level but almost 40% had education to less than GCSE level. Sixty-nine per cent had an income that was lower than the national average.

Descriptive analysis of perceptions of attractiveness is summarised in Table 2 and shows that, at mild levels of dental fluorosis, where pictures of teeth with TF scores of 1 and 2 were shown; 61% perceived fluorosed teeth as attractive, 34% perceived them as unattractive and 5% were neutral in their judgment. When pictures of fluorosis of TF scores of 3 and 4 (moderate level) were shown, the proportion of respondents perceiving the teeth as attractive was almost halved (36%) and the percentage perceiving teeth as unattractive increased to 63%. At this level fewer people were neutral in their judgment. Even more widespread agreement was seen in perceptions of attractiveness at the severe level of fluorosis. When pictures of teeth showing TF scores ≥ 5 were shown 99% of subjects perceived them to be unattractive.

Perceptions of satisfaction (summarised in Table 3) followed a similar pattern to that seen in perception of attractiveness. Perception of satisfaction decreased from 60% at the mild level to 40% at the moderate and to less than 1% at the severe level. The proportion of respondents who were dissatisfied increased from 36% at mild levels to 58% at the moderate and to over 99% in the case of severe fluorosis. The proportion of those who were neutral in their judgments decreased from 4% at the mild level to less than 1% at each of the moderate and severe levels.

Perception of treatment need differed slightly from perception of attractiveness or satisfaction (Table 4). Twenty-nine per cent of the study population perceived a definite need for treating mild levels of fluorosis, this percentage increased to over two thirds (69%) when pictures of moderate fluorosis were presented, and the majority (91%) perceived a need for treatment for severe levels of fluorosis. The level of uncertainty was higher than that seen in perception of attractiveness and satisfaction at moderate and severe levels of fluorosis but lower in the case of mild fluorosis.

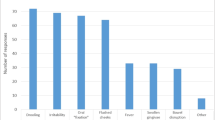

The percentages of respondents regarding cases as showing aesthetically objectionable fluorosis are illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 1. Fourteen per cent (467) of respondents suggested that the mild level of dental fluorosis is aesthetically objectionable. At the moderate level, the percentage was 45% (1,500). In the case of severe fluorosis 91% (3,035) of respondents indicated that teeth with this level of fluorosis were unattractive, unsatisfactory and required treatment.

Discussion

This study is the first of its kind to study perceptions of dental fluorosis on a national level in the United Kingdom. The Office of National Statistics Omnibus Survey represents an established and reliable means of obtaining information about the general population or about particular groups of people. It is also the only national survey to use random probability sampling at all stages of sample selection.

Findings from this study suggest that perceptions of unattractiveness, dissatisfaction and treatment need increase with increasing severity of dental fluorosis, a result in line with previous findings6,7,8,9,10,12,13 and indicating that greater severities of fluorosis have an adverse effect on aesthetics.

Severe fluorosis was reported to be aesthetically objectionable by 91% of the study participants, a result that is again close to findings from previous studies.13

However, although there was agreement in terms of broad trends and at severe levels of fluorosis, there were differences when less severe levels of fluorosis were considered. Only 14% of the population were found to perceive mildly fluorosed teeth as aesthetically objectionable, a result which is lower than has been reported previously.6,8,9,10,12,13 In past studies the percentage of subjects regarding mild fluorosis as unacceptable has ranged from 19%9 to 45%.8 In the current study 45% of the sample also perceived moderate fluorosis as aesthetically objectionable, again a level lower than in previous reports, eg 58% by Clark et al.,10 47% by Riordan,6 89% by Hawley et al.,9 52% by Ellwood and O'Mullane8 49% by Woodward et al.12 and 71% by Lalumandier and Rozier.13 This variation in the level of what may be regarded as aesthetically objectionable or unacceptable fluorosis is of clinical relevance.

Past studies used different methods to assess aesthetically objectionable fluorosis; variations have included differences in the indices used to grade fluorosis and in the way 'aesthetically objectionable' or 'unacceptable' was measured. In most cases the measure was based on single parameters such as dissatisfaction, concern, unhappiness or just being unacceptable in general terms. In the present study however, three parameters were used to calculate aesthetically objectionable fluorosis. The combination of the three perceptions of 'attractiveness', 'satisfaction' and 'treatment need' may provide a more meaningful overall perception of acceptability and unacceptability. Using this measure, levels of unacceptable or objectionable dental fluorosis reported in this study may therefore be more realistic. The inclusion of perceived treatment need in the assessment of unacceptability may be also regarded as increasing the validity and practical value of the term 'unacceptable'.

The present study used a large, nationally based sample of adults. This is in contrast to previous studies, which have often been based on much smaller and more selected groups. Details of differences within the large sample included here are beyond the scope of this paper, but Riordan6 has already reported on differences between at least some groups. Between 23 and 30% of subjects included in a study sample regarded mild levels of fluorosis as unacceptable, depending on assessment groups. Groups included students, parents and dentists.6 Although differences are therefore known to exist, use of a large sample, selected randomly, would however seem the most appropriate method for policy making for the population in the first instance.

Although estimates of aesthetically objectionable fluorosis were lower than reported previously, a finding that 14% of the population regarded even mild levels of fluorosis to be aesthetically objectionable remains a cause for concern. However, this finding needs to be balanced against at least two factors. Firstly, 3% of respondents also considered teeth without any evidence of fluorosis as aesthetically objectionable although the picture showed no evidence of defect and it is difficult to establish which aspects of dental appearance caused these negative perceptions. The clear benefit of water fluoridation lies in caries prevention and the second factor that should be taken into account is the aesthetic impact of caries; had an image of caries in anterior teeth been included and respondents asked for their perceptions or, to choose between the risk of mild fluorosis or caries, a very different picture may have emerged. Thus, perceptions of apparent disadvantages must, in the final judgement, be balanced against benefits.

Conclusion

Findings of this study suggest that dental fluorosis causes aesthetic concern at moderate and severe levels. The proportion of the population perceiving mild levels as aesthetically unacceptable is also appreciable. However, reasons for objections to dental appearance are not wholly clear at this level of defect. More detailed investigations into variations in aesthetic values are needed if the sole influence of fluorosis on these trends is to be more clearly understood. Further research is also encouraged to validate our use of the term 'aesthetically objectionable', comparisons with professional judgment of aesthetically objectionable fluorosis on a wide scale would be also useful to expand the knowledge in this field. The present study has laid foundations for assessment of the likely impact of water fluoridation on the public perception of consequent dental appearance.

References

Mandel I . The image of dentistry in contemporary culture. J Am Dent Assoc 1998; 129: 607–613.

Welie J . Do you have a healthy smile? Med Health Care Philos 1999; 2: 169–180.

NHS CRD. A systematic review of public water fluoridation. York:NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. University of York, 2000.

Van Palenstein Helderman WHV, Mksasabuni E . Impact of dental fluorosis on the perception on the perception of well-being in an endemic fluorosis area in Tanzania. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1993; 21: 243–244.

Rozier RG . The prevalence and severity of enamel fluorosis in North American children. J Public Health Dent 1999; 59: 239–246.

Riordan PJ . Perceptions of dental fluorosis. J Dent Res 1993; 72: 1268–1274.

Riordan PJ . Specialist clinicians' perceptions of dental fluorosis. J Dent Child 1993; 60: 315–20.

Ellwood R, O'Mullane D . Enamel opacities and dental esthetics. J Public Health Dent 1995; 55: 101–106.

Hawley GM, Ellwood R, Davies R . Dental caries, fluorosis and cosmetic implications of different TF scores in 14-year-old adolescents. Comm Dent Health 1996; 13: 189–192.

Clark DC, Hann HJ, Williamson MF, Berkowitz J . Aesthetic concerns of children and parents in relation to different classifications of the Tooth Surface Index of Fluorosis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1993; 21: 360–364.

Thylstrup A, Fejerskov O . Clinical appearance of dental fluorosis in permanent teeth in relation to histologic changes. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1978; 6: 315–328.

Woodward GL, Main PA, Leake JL . Clinical determinants of a parent's satisfaction with the appearance of a child's teeth. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1996; 24: 416–418.

Lalumandier JA, Rozier RG . Parents' satisfaction with children's tooth color: fluorosis as a contributing factor. J Am Dent Assoc 1998; 129: 1000–1006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alkhatib, M., Holt, R. & Bedi, R. Aesthetically objectionable fluorosis in the United Kingdom. Br Dent J 197, 325–328 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811651

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811651

This article is cited by

-

Are there good reasons for fluoride labelling of food and drink?

British Dental Journal (2018)

-

Should food and drink have fluoride labels?

BDJ Team (2018)

-

Investigation of the value of a photographic tool to measure self-perception of enamel opacities

BMC Oral Health (2012)